Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Janus in the Roman Coinage

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Janus in the Roman Coinage

In construction

Early Roman Bronze Coinage

Aes Signatum

The first ten ‘coins’ from the mint at Rome that appear in the catalogue of Michael Crawford’s ‘Roman Republican Coinage’ (referenced below, entries RRC 3/1 - RRC 12/1) were actually very heavy ingots or currency-bars known as aes signatum (stamped bronze). As Eric Kondratieff (referenced below, at p. 27) explained:

“The aes signatum was, in fact, Rome’s largest single bronze denomination ever.”

Crawford suggested (at p. 716) that these ingots were produced in the period 280 -260 BC, although, as we shall see, this was no more than a rough indication. He pointed out (at p. 41, note 5) that:

“... aes signatum can hardly have been intended for storage, for which, its types in high relief make it wholly unsuitable. Nor can it be [either] moneta privata or Greek, since [it forms a homogeneous group and] some of its types, [RRC 3/1 and RRC 4/1] bear the legend ROMANOM. ... The almost uniformly martial types suggests the hypothesis that [it] for was created for the distribution of of booty after a victory. In any case, it is clear that, ...once issued, [it] was treated as bullion.”

If I have understood this correctly, then Crawford suggested that:

✴whole ingots were produced after Roman victories in order to monetise war booty (and the designs stamped on each of them presumably commemorated the victory in question);

✴these high-value ingots were then distributed among the victorious solders (and, presumably, sometimes to other privileged recipients); and

the recipients could then break them up into fragments and use them as ‘coins’, the value of which was determined by weight.

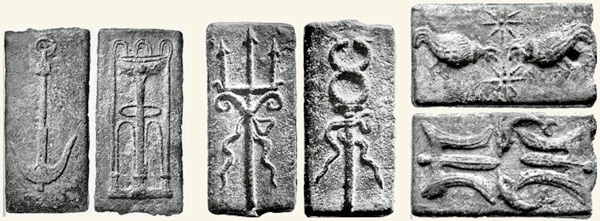

‘Naval’ Aes Signatum

‘Naval’ aes signatum (images adapted from Eric Kondrieff (referenced below, at pp. 36-7, figs 4, 5 and 6a)

(RRC 10) anchor/ tripod (RRC 11) trident/caduceus (RRC 12) feeding cocks and stars/

(symbolising Neptune and Mercury) rostra and dolphins

Michael Crawford (referenced below, at p. 41) argued that, since each of the three ingots illustrated above had naval symbolism (anchor/ trident/ rostra and dolphins respectively) stamped on one of its sides:

“... it is hard to imagine all or any of [them] as being produced before Rome became a naval power during the First Punic War”.

Eric Kondratieef (referenced below, at p, 28) was more specific: the ‘naval’ aes signatum:

“... would have been issued only after Rome finally became a legitimate maritime power with Duilius’ victory at Mylae.”

He referred here to C. Duilius (cos. 260 BC), who, according to the entry for that year in the Augustan fasti Triumphales, was awarded:

“... the first naval triumph, over the Sicilians and the Carthaginian fleet”.

He summarised (at p. 34) the hypothesis that he developed in his paper as follows:

“Duilius has long been acknowledged as:

✴the first Roman to win a sea-battle;

✴the first to be honoured with a rostral column; and

✴the first to present a gift derived from naval booty to the Roman people.

Indeed, he came to be seen primarily as the man who set Rome on the road to maritime expansion and, ultimately, domination of the Mediterranean world. He was remembered also as the first (if not only) man to have a flute-player and wax-torch bearer accompany him home from feasts, as if he were triumphing all the time. Now, we might add to Duilius’ list of firsts: he was the first politician to utilise Roman ‘coinage’ to its fullest extent, to broadcast a new ideology of Rome’s (hoped-for) naval greatness and dominance of the Mediterranean; he was also, it seems, the first Roman politician to use coinage as a medium for self-promotion, a century and a quarter before anyone would do it again.”

Thus, Kondratieff argued that Duilius issued all of RRC 10-12 in order to facilitate the distribution of booty to the Roman people at his triumph in 260 BC. However, this might well stretch the surviving evidence too far: for example:

✴did Duilius have any legal right to issue coinage on behalf or the State, or was Crawford nearer the mark when he suggested (at pp. 62-3 and 602) that, in this period, the censors were responsible for the coinage;

✴would it have been logistically possible to have produced these putatively unprecedented ingots in time for the triumph of 260 BC and to arrange for their wide distribution without provoking a riot; and

✴why would Duilius have added to his logistical problems by issuing three types when one would have sufficed.

I think that the hypothesis can be refined if we look at the naval triumphs that followed in quick succession.

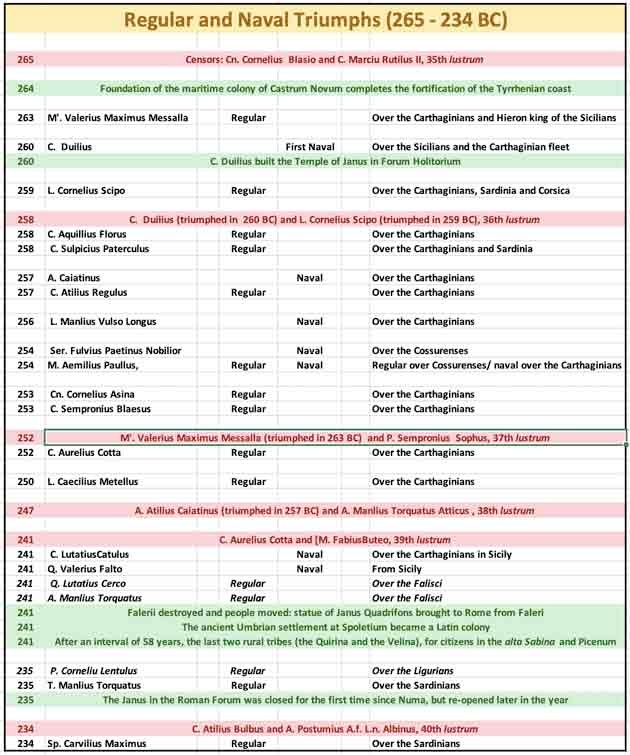

Triumphs from the fasti Triumphales; Censorships from the fasti Capitolini

The table above shows that seven naval triumphs were celebrated during the war, in three temporal groups:

✴Duilius ‘ triumph of 260 BC;

✴four more in 257-4 BC; and

✴two more in 241 BC.

Thus, it is possible that each of the three ‘naval’ types of aes signatum was uniquely associated with one of these groups of triumphs. For example

Duilius might be the link between Janus and the Roman coinage: according to Tacitus, in 17 AD, the Emperor Tiberius:

“... dedicated [a number of] temples that had been ruined by age or fire and restored by [the recently-deceased] Augustus. These included ... Iano templum (the shrine of Janus), which had been built in the Forum Holitorium by C. Duilius, who primus rem Romanam prospere (was the first Roman to mount a successful naval campaign) and [thereby] earned a naval triumph over the Carthaginians”, (‘Annals’, 2: 49).

Aes Grave/ Libral

Early aes grave (heavy bronze) as (RRC 14/1) minted in Rome in the 3rd century BC

Janiform (two-faced) beardless head, identified as Janus or a representation of the Dioscuri (see below)/

Head of Mercury (identified by winged helmet). Denomination mark I (= as) on both sides

Early aes grave (heavy bronze) as (RRC 18/1) minted in Rome in the 3rd century BC

Head of Apollo, right, with hair tied back with band/ Head of Apollo, left, with hair tied back with band. Denomination mark I = as ( on both sides)

The first coins (as we understand the term) that were minted in Rome are classified as:

✴aes grave (heavy bronzes); or, more specifically

✴aes librale (bronzes in denominations at least nominally related to the libra (Latin pound = 273 gm).

Initially, these bronzes were cast (rather than struck /hammered). Liv Yarrow (referenced below, 2023, at p. 110) observed that they were characterised by a surprisingly elaborate denomination system and that:

“The inclusion of denomination marks on the coins themselves [see the examples of the asses illustrated above] makes clear the importance of the denomination system to this new form of coinage.”

As she set out in her Table 6. 1, at p. 107), the issues comprised seven denominations, ranging from

✴the as (nominally weighing 12 unciae = 1 libra); to

✴the semiunica (nominally weighing one 24th of a libra).

Michael Crawford (referenced below, at pp. 131-3) catalogued the the asses of the earliest aes grave as RRC 14/1, RRC 18/1 and RRC 19/1 (although very few specimens of the third issuesurvive).

It is interesting to note that some of the coins from these three issues feature heads on both sides, and at least some them are usually identified those of deities:

✴14/1 (as): beardless Janus* or conjoined heads of the Dioscuri/ Mercury

✴14/2 (semis): Minerva/ unidentified female; or Mars/ Venus*

✴18/1 (as): Apollo/ Apollo

✴18/5 (sextans): one of the Dioscuri/ one of the Dioscuri

✴19/1 (as): one of the Dioscuri/ Apollo

✴19/2 (semis): unidentified female or Faunus*/ Roma (wearing Phrygian helmet)

Unsurprisingly, given the age (and thus the heavy wear) of the coins and the rarity of some of them, these identifications are open to dispute. For the purposes of this page, we might simply note that, in the three cases of dispute flagged by asterisks above, Liv Yarrow (referenced below, 2023, at p. 107, Table 6. 1), in her recent and detailed study of these issues, cited:

✴Maria Cristina Molinari (referenced below) for the identification of the beardless two-face god on RRC 14/1 as Janus (rather than as a representation of the Dioscuri);

✴Ernst Haberlin (1910) and Rudi Thomsen (referenced below, at p. 59) for the identification of the male had on RRC 14/2 as Mars (rather than Minerva, which would indicate the hfmale head on the other sire is Venus;

✴Françoise-Hélène Massa-Pairault (referenced below, para 29) for the identification of the unidentified head on RRC 19/2 as Faunus.

The most important of these identifications for the present purpose is that of Janus (alongside Mercury) on 14/1, to which I will return.

As Liv Yarrow (referenced below, 2023, at p. 109) pointed out, Crawford (above) followed earlier scholars in assuming that:

✴the asses of RRC 14/1 had been intended to weigh one libra; and

✴since those of RRC 18/1 seemed to have been heavier (or, in the jargon, supralibral), they must have been issued later.

She pointed out that, in 1974, Michael Crawford (referenced below) had therefore assumed that the first of these series had been issued 5-10 years before the second. However, Yarrow (as above, at p. 121) reported that:

“While, on average, RRC 18 specimens do seem to be slightly heavier than [those from] RRC 14, ... [this as not statistically significant]: ... both issues produced specimens that significantly differed from any apparent target or weight standard.”

She also noted (at p. 110) that:

“The inclusion of denomination marks on the coins themselves [discussed above] makes clear the importance of the denomination system to this new form of coinage. ... The coin itself [proclaimed] its worth ... , [so that it did not need to conform to an exact weight standard].”

She therefore reasonably concluded (at pp. 127-8) that:

“The designation of RRC 18/1 ... as ‘supralibral’ ... should be abandoned, [and] we can no longer support this chronological seriation on these grounds. It would be better:

✴to assign [both RRC 14 and RRC 18] to approximately the same period, some time in the decade prior to the First Punic War; and

✴to remain agnostic about resolving their sequence further until better evidence or hoard data emerges.”

Liv Yarrow (referenced below, 2023, at p. 108) observed that:

“... our best evidence for dating the early [aes grave] comes from the work of [Alessandro Maria Jaia and Maria Cristina Molinari, referenced below, who reported on] two foundation deposits at the fortified Sanctuary of Sol Indiges [at Torvaianica], along the coast below Lavinium, [which contained] both RRC 14 and 18, but no later issues”, (my slightly changed word order).

Jaia and Molinari listed the coins found at Torvaianica (at Appendix I) and included them in the list of the nine hoards on the Tyrrhenian coast that all contained both RRC 14 and 18, but no later issues (at Appendix II). They pointed out (at p. 91) that:

“The rearrangement of the coastal sanctuary of Sol Indiges at Lavinium, ... with its emphasis on defensive structures, should not be considered as an isolated initiative ... [It formed part of] a vast and well-coordinated system [of colonisation and fortification] designed to ensure [Roman] control over the Tyrrhenian coast ...”;

and conclude (at p. 93) that:

“The construction of this system of defence and production could partially explain the initial spread and destination of the libral aes grave, attested (not surprisingly) during the completion of the process of the colonial settlement of Latium vetus and northern Campania, and during the first stages of the coastal colonisation o southern Etruria (in the latter context note the hoard of Santa Marinella, in the area of Castrum Novum, [the site of a maritime colony founded in 264 BC]. Furthermore, the use of public money to build this defensive belt would prove its worth when the Carthaginian fleet attacked the coast of Italy from its bases in Sardinia, especially if, as stated by Polybius [(‘Histories’, 1: 56: 10), Carthaginian] ships stationed in Sicily could also raid as far as the city of Cumae.”

It seems to me that, while this scenario is plausible:

✴the only hard chronological datum from this analysis is that RRC 14 and 18 were extant in or relatively soon after 264 BC; and

✴the wide range of denominations found in these hoards (particularly at Ardea: 21 asses; 30 semisses; 45 trietes; 40 quadrates; 15 sextantes; and 8 uniciae) arguably militates against a hypothesis involving State expenditure.

Janus and the Prow Asses

Cast heavy bronze as (RRC 35/1): bearded Janus/ prow: denomination mark 1 (= as) on both sides

The as above was the first of no fewer than 88 Janus/prow asses that were minted in Rome: the last of this series (RRC 354/2) was issued by C. Licinius Macer in 84 BC. Thereafter, asses with essentially the same iconography were produced in military or provincial mints for:

✴Sulla (RRC 368/1), in 82 BC;

✴Caesar (RPC-2273, Lampsacus), in 45 BC;

✴Sextus Pompeius (the son of Pompey the Great):

•RRC 47/1 , in 46-5 BC; and

•RRC 479/1, in 45 BC, although, on this coin, ‘Janus’ had the features of Pompey the Great; and

✴Mark Antony and L. Sempronius Atrantinus (RRC 530/1), in 39 BC.

Writing in the early 1st century AD, Ovid, in his ‘Fasti’. imagined interviewing Janus at the start of the month that is named for him. He first addresses him as follows:

“Iane biceps (two-headed Janus), the source from which the silently passing year originates, ... favour our duces (commanders), whose labours win peace for the fertile earth [and] peace for the seas”, (‘Fasti’, 1: 65-8, based on the translation by James Frazer, referenced below, at p. 7).

Ovid then felt able to ask the mysterious Janus some questions (presumably for the benefit of his readers), the first of which is as follows:

“But, Iane biformis (double - shaped Janus), what god shall I say you are (since Greece has no divinity like you)?”, (‘Fasti’, 1: 89-90, based on the translation by James Frazer, referenced below, at p. 9).

A little while later, he came to the question that concerns us here:

“... why is there a ship stamped on one side of the aere (bronze asses) [and] forma biceps (a two-headed form) on the other? [Janus answered]:

‘You might have recognised me under the double-image, if [long use] had not worn the coin away’”, (‘Fasti’, 1: 229-32, based on the translation by James Frazer, referenced below, at p. 19).

Janus’ explanation for the presence of the ship need not detain us at this point. What we can take from these passages is that Ovid felt that he should remind his readers that Janus was the two-headed god depicted on the prow asses. (Note however, that Janus did not appear on the obverses of other denominations of the ‘prow reverse’ series: Saturn usually appeared on the semisses; Minerva on the trietes; Hercules on the quadrates; Mercury on the sextantes; and Roma on the unciae (as in, for example RRC 35/ 1-6).

Macedonian tetradrachm

Obverse: Bearded head of Poseidon, with flowing hair bound with a sea-plant/

Reverse: Apollo, holding a bow, seated on the prow of a ship, the ram of which is tipped with a trident-head

On side of the ship: BAΣIΛEΩΣ/ ANTIΓONOY (of Basilieus/referred to the )

Michael Crawford (referenced below, at p. 42 and note 5) suggested that:

“... the Prow series of aes grave ... seems to portray a type of prow otherwise first found on the coinage of Antigonus [III] Donos, [King of Macedon], in an issue struck after 227 BC, ... [and] may reasonably be regarded as belonging to the same period.”

I have not been able to consult the sources he gave at note 5, but presume that he referred to the tetradrachm illustrated above. However, most scholars identify the issuer as Antogonus II Gonatus. For example, Sophia Kremydi (referenced below, at pp. 171-2) observed that Gonatus only secured his position in Macedon:

“... after the death of [Pyrrhus] in 272 BC. Recent research based on hoard evidence has shown that [he] inaugurated his personal coinage during the Chremonidian War in [ca.] 268/7 BC. ... The iconography of Antigonus' coinage shows a clear rupture from that of his father's: he neither placed his portrait on his coins, nor continued any other of Demetrius' types. ... It was probably towards the end of his reign that the so-called Poseidon tetradrachms were introduced. Their iconography (head of Poseidon/Apollo on prow) clearly refers to Antigonus' naval aspirations in the Aegean and his rivalry with the Ptolemies [of Egypt]. A date just after 246/5 BC (that is ,after his victory over Ptolemy II near Andros) seems very probable. ... Both [this and an earlier tetradrachm with the legend ΒΑΣΙΛΈΩ Σ ΑΝΤΙΓΌΝΟΥ continued to be issued under Gonatas 'successors:

✴his son Demetrius II (239-229 BC ) and

✴Antigonus Doson (229-22 1 BC);

✴who did not introduce personal types.”

More recently, Robin Waterfield (referenced below, at pp. 175-6, reviving a hypothesis put forward by Tarn, referenced below in 1910) put forward an earlier date:

“In commemoration of his great victory at Cos [in 261 BC, Gonatus] made [an] unusual dedication on Delos: he found space somewhere (we do not know where] to make a commemorative monument out of his entire flagship, ... He also minted a celebratory issue of gold coins and a new silver tetradrachm, [which] showed Apollo of Delos sitting on the prow of a warship, indicating his [i.e., Gonatus’] dominance at sea.”

Michael Crawford (referenced below, at pp. 41-2, note 5) pointed out that, although all ten known examples of the aes signatum had been catalogue first:

“... I am sure [that they were] contemporary with the first four aes graves: not only [do all of these issues share the same] the hoard context ... but all of the issues whose types convey any indication of date must be of (or of the period later than) the Pyrrhic War [280-75 BC]. ... ... As for function, ... [the] almost uniformly martial types [of the designs on these ingots] suggest the hypothesis that the aes signatum was created for the distribution of booty after a victory ”

Importantly for our purposes, he also observed (at p. 718) that the iconography of what he believed were the last three aes signatum (his RRC 10, RRC 11 and RRC 12 illustrated above):

“... apparently allude to [the Roman’s] success in the First Punic War.”

Eric Kondrieff (referenced below, at p. 28) argued that:

“Hoard evidence confirms that the first aes signatum with naval imagery can be dated (approximately) to the beginning of the First Punic War. One particularly illuminating hoard was found at La Bruna, Italy in 1890. It contained 8 complete bars of aes signatum, each bearing martial types; one fragment of a non-Roman bar; and 8 heavy (335 gm) asses [see below], which had been phased out in the early 260s BC ... The group of aes signatum in the hoard] yielded three types with naval symbolism, [obviously, those illustrated above], which [probably] would have been issued only after Rome finally became a legitimate maritime power with Duilius’ victory at Mylae [in 260 BC- see below]. Since relative-dating evidence from other hoards indicates that the remaining pieces of the La Bruna hoard were issued during or after the Pyrrhic War, and all come from the earlier series of heavy bronze issues, the aes signatum carrying naval imagery must be considered the most recent. Finally, since the chronological gap between the latest heavy asses and earlier aes signatum was probably not more than a few years, it seems likely that the aes signatum with marine imagery was

issued at the earliest possible opportunity for Rome to claim mastery of the sea, ca. 260.

Taken together, the apparent date and marine imagery of this aes signatum strongly

suggest that Duilius himself had it issued to distribute at his triumph

these three issues dated

… [and], in any case, it is clear that aes signatum, once issued, was treated as bullion ...

Eric Kondrieff (referenced below, at p. 20) argued that, the inscription above suggests that, during his campaigns at Segesta, Marcella and Mylae:

“Duilius captured 1,069 - 1,247 tons of bronze, equivalent to 3.5 to 4.1 million asses in actual coinage (at the weight of ca. 270 gm per as). That he would claim to have acquired such a huge quantity of bronze seems at first sight incredible. ... [However], there is a near-contemporary, near-equivalent precedent cited by Livy [at ‘History of Rome’, 10: 46: 2-6], for the year 293 BC, a generation before Duilius’ consulship.”

He also argued (at pp. 25-7) that:

“... the inscription’s claim that Duilius gave naval booty to the people ‘at his triumph’ ... [indicates] that Duilius actually shared some of [this] wealth with the citizens after the customary distributions to his own soldiers. [If so, then the] next question is: how, and in what form, was so much money distributed? ... [He] would have needed a very large amount of bronze coinage and a convenient format in which to distribute [it], such as the aes signatum, a special, multiple-as bronze coinage which required smaller numbers to distribute larger cash values.”

Eric Kondrieff (referenced below, at p 28) set out to prove that:

He reinforced the points made by Crawford (above), adding (at p. 30) that each of them:

“... includes one certainly maritime image [anchor/ trident/ rostra and dolphins] and another, somewhat ambivalent image that could also relate to victories on land. Of course, none can doubt that Duilius intended to celebrate his achievements in both spheres of activity, since ... the [inscription above] emphasises details of his capture of Segesta and Macella as well as those of his naval victory at Mylae.”

Janus and the Early Aes Grave

According to the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus (as epitomised by Festus):

“Malevoli Mercurii signum erat proxime Ianum; qui tem erat in Turdellis M ... appellabatur. Malevoli autem, quod in nullius tabernam spectabat”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 152 L):

.

Read more:

Yarrow L. M., “The Strangeness of Rome’s Early Heavy Bronze Coinage”, in:

Bernard S, Mignone L. and Padilla Peralta D. (editors), “Making the Middle Republic: New Approaches to Rome and Italy (ca. 400-200 BC)”, (2023) Cambridge, at pp. 103-30

Waterfield R., “The Making of a King: Antigonus Gonatas of Macedon and the Greeks”, (2021) Oxford

Yarrow L. M., “Not All Elephants (are Pyrrhic): Finding a Plausible Context for RRC 9/1”, Ancient Numismatics, 2 (2011) 9-42 (Final pre-publication text opens as pdf)

Molinari M. C., “The Two Roman Types with Two-Faced Gods on Third century BC Coinage”, in:

Elkins N. T. and Krmnicek S., (editors), “Art in the Round: New Approaches to Ancient Coin Iconography”, (2014) Rahden, at pp. 89-96

Jaia A. M. and Molinari M. C., “Two Deposits of Aes Grave from the Sanctuary of Sol Indiges: the Dating and Function of the Roman Libral Series”, Numismatic Chronicle, 171 (2011) 87-97

Kremydi S., “Coinage and Finance”, in:

Lane Fox R. J., (editor), “Studies in the Archaeology and History of Macedon (650 BC-300 AD)”, (2011) Leiden, at pp. 159-78

Massa-Pairault F.-H., "Romulus et Remus: Réexamen du Miroir de l'Antiquarium Communal" Mélanges de l'École Française de Rome: Antiquité, 123-2 (2011) online

Kondratieff E., “The Column and Coinage of C. Duilius: Innovations in Iconography in Large and Small Media in the Middle Republic”, Scripta Classica Israelica, 23 (2004) 1-39

Crawford M., “Roman Republican Coinage”, (1974) Cambridge

Thomsen R., “Early Roman Coinage, Vol. 1”, (1957) Copenhagen

Frazer J. J. (translator), “Ovid:Fasti”, (1931) Cambridge MA

Tarn W. W., “The Dedicated Ship of Antigonus Gonatas”, Journal of Hellenic Studies, 30 (1910) 209-22

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)