Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Sack of Rome (390 BC) to the

Renewal of Peace with the Latins (358 BC)

Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Sack of Rome (390 BC) to the

Renewal of Peace with the Latins (358 BC)

Camillus’ Victories of 389 BC

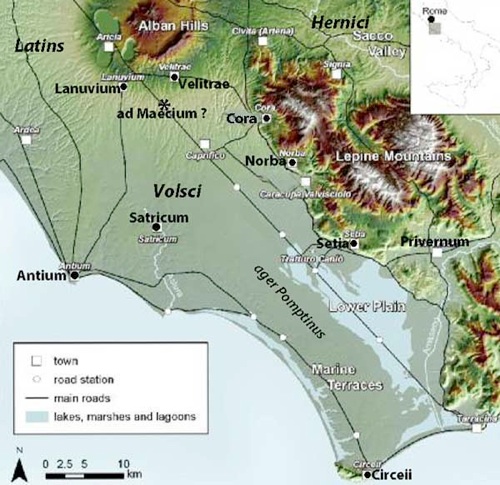

Adapted from Livius.org: Map of Latium, ca. 400 BC

Camillus’ Third Dictatorship

Livy recorded that two interreges were appointed in succession after the sack of Rome in order to elect the consular tribunes for 389 BC:

“The interregnum began with P. Cornelius Scipio as the first interrex; he was followed by M. Furius Camillus, under whom the election of military tribunes was conducted. Those elected were

✴L. Valerius Publicola, for the second time [DS: Valerius = L. Valerius Poplicola II];

✴L. Verginius [Chron 354 AD: Tricosto; DS: L. Verginius = L. Verginius Tricostus Esquilinus (II?)];

✴P. Cornelius [DS: P. Cornelius = P. Cornelius];

✴A. Manlius [DS: A. Manlius = A. Manlius Capitolinus];

✴L. Aemilius [DS: omitted = L. Aemilius Mamercinus II]; and

✴L. Postumius [Chron 354 AD: Albino; DS: Lucius and Postumius (sic) = L. Postumius Albinus Regillensis]”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 1: 8).

The record in the fasti Capitolini for this year no longer survives: in the square brackets above: Chron 354 AD = Chronography of 354 AD (for 365 AUC); DS = Diodorus Siculus, who recorded a college of four tribunes but named only three (‘Library of History’, 15: 22: 1). Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at pp. 391-2) argued that two further names given by Diodorus, L. Papirius and M. Furius, can be discounted. Thus, in all probability, Camillus presided over the election of a ‘normal’ college of six patrician consular tribunes.

Livy then reported that, although the Gallic crisis had receded, the Romans:

“... were not ...long left undisturbed:

✴ On the one side, the Volscians, their ancient foes, had taken up arms in the determination to wipe out the nomen Romanum (Roman name);

✴on the other side, traders were bringing in reports Etruriae principum ex omnibus populis (all the peoples of Etruria) were plotting war ad fanum Voltumnae (at the shrine of Voltumnus).

✴Still further alarm was created by the defection of the Latins and Hernicans, [despite the fact that] these nations had never wavered in their loyal friendship with Rome ... [since] the battle of Lake Regillus [in ca. 500 BC].

As so many dangers were threatening on all sides, it became evident the name of Rome was not only held in hatred by her foes: it was also regarded with contempt by her allies. The Senate [therefore] decided that Rome should be defended under the auspices of the man by whom it had been recovered [from Gallic occupation], and that Marcus Furius Camillus should be nominated dictator [for a third time]”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 2: 1-5).

Camillus’ Victory over the Volsci ad Maecium (389 BC)

Prior Events

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 333) noted that the Volscians had overrun a number of places in the Latin plain south of Rome in the 5th century, notably: Antium; Circeii; Cora; Satricum; Tarracina; and Velitrae. He also noted (at p. 347) that, according to Diodorus Siculus, the Romans had begun to make inroads here before the Gallic sack:

✴at Velitrae in 404 BC (‘Library of History’, 14: 34: 7); and

✴at Circeii, in 393 BC (‘Library of History’, 14: 102: 4).

Victory ad Maecium

Immediately after his appointment as dictator for the second time in 389 BC, Camillus:

“... advanced to attack [the Volscian] camp at a place called Ad M[a]ecium, not far from Lanuvium. ... The enemy were routed and cut to pieces. ... In the pursuit [of fleeing enemy soldiers, Camillus] ravaged the length and breadth of the Volscian territory and at last forced them to surrender after 70 years of war”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 2: 7-13).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at pp. 350-1) observed that:

“There is no compelling reason to reject the battle ad Maecium, and its authenticity is confirmed by Livy’s reports of Roman activity in the Pomptine area [to the south of it] in the following years [see below].”

(Oakley addressed the correct rendering of ‘ad Maecium’ and its possible location at p. 407).

Camillus’ Victory over the Aequii (389 BC)

Prior Events

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 412) noted that the Aequii:

“... in alliance with the Volsci, [had provided] formidable opposition for Rome and the Latins in the 5th century BC. ... [They] are first mentioned as foes of Rome in 488 BC, and fighting was then regular from 465 to 408 BC, by which time Rome clearly had the upper hand. Thereafter, there were sporadic campaigns in 397, 394 and 392 BC, which provided the context of the fighting of 389 BC.”

Capture of Bolae (389 BC)

According to Livy:

“From his conquest of the Volscians, Camillus marched across to the Aequi who were also preparing for war, surprised their army ad Bolas and, in the first assault, captured not only their camp but their city”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 2: 14).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 412) noted that, although the location of Bolae is now unknown, it was probably near the Latin city of Labicum. He pointed out that, after its fall in 389 BC:

“The Aequii remained at peace with Rome until [the Aequan War of 304 - 300 BC], when they suffered their final defeat.”

Camillus’ Rescue of Sutrium (389 BC)

According to Livy, when Camilius had marched against the Volsci (as above), he had left two military divisions behind:

“He stationed one in the Veientine territory fronting Etruria, [while the] second was ordered to form an entrenched camp to cover the City; A. Manlius, as military tribune, was in command of [the latter] division, while L. Aemilius, in a similar capacity, commanded those sent to face the Etruscans”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 2: 7-8).

It seems to me that these were purely defensive measures, and that both positions had been chosen so that these two divisions could guard against an Etruscan incursion into Roman territory.

The need for such a strategy was soon demonstrated: while Camillus was still in Volscian and Aequan territory, news reached Rome to the effect that:

“... a terrible danger was threatening: Etruria prope omnis (nearly the whole of Etruria) was in arms and was besieging Sutrium, socio populi Romani (a city in alliance with Rome)”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 3: 1-2).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 347) observed that Sutrium (and nearby Nepete) stood on land that must have been confiscated from Falerii in 394 BC, which would explain why the people of Sutrium now enjoyed the protection of Rome. Thus:

“Their envoys approached the Senate with a request for help ... The Senate passed a decree that the dictator Camillus should render assistance to them as soon as he possibly could. [However, he was fighting against the Volscians and the Aequans at that time, and his help was almost too late]: the people of Sutrium had made a conditional surrender of their city. As the mournful procession set forth, leaving their hearths and homes, ... Camillus and his army happened ... to appear on the scene. ... He ordered the Sutrines to remain where they were and ... marched to Sutrium, [which he took] before the Etruscans could [prepare its defence]. Thus, Sutrium was captured twice in the same day; ... Owing to the great number [of Etruscan prisoners-of-war], they were distributed in various places for safe keeping. Before nightfall the town was given back to the Sutrines uninjured and untouched by all the ruin of war...”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 3: 2-10).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at pp. 347-8 and note 56) argued that, although the details of the engagement at Sutrium are highly suspect, the underlying fact that the Etruscans attempted to profit from Rome’s distractions should not be doubted.

Camillus’ Triumph (389 BC)

According to Livy:

“Camillus returned in triumphal procession to the City, after having been victorious in three simultaneous wars. By far the greatest number of the prisoners who were led before his chariot belonged to the Etruscans: they were publicly sold, and so much was realised that. after the matrons had been repaid for the gold [that they had lent to the state in the previous year], three golden bowls were made from what was left. These bowls were inscribed with the name of Camillus, and it is generally believed that, prior to the fire in the Capitol [in 83 BC], they were deposited before the feet of Juno in the [cella devoted to her in the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus]”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 4: 1-3).

We might reasonably assume that Camillus resigned his dictatorship at this point, albeit that Livy made no reference to this,

Etruria (388 - 383 BC)

Likely locations of the new voting districts of 387 BC (Tromentina, Arnensis, Sabatina, Stellatina)

Red squares = Colonies at Sutrium and Nepet (386-383 BC)

After Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, second end map)

Adapted from Linguistic Landscape of Central Italy

Roman Advance towards Tarquinii (388 BC)

Livy recorded that, in the year that followed Camillus’ triumph, a Roman army:

“... advanced into the district of Tarquinii. There, [the now-unknown] Cortuosa and Contenebra, towns belonging to the Etruscans, were taken by assault:

✴At Cortuosa there was no fighting: the garrison were surprised and the place was carried at the first assault.

✴Contenebra withstood a siege for a few days, but the incessant toil ... proved too much for [its inhabitants]”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 4: 8-9).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 348 ) observed that:

“... we may doubt the details but we should accept the outline, since Rome would have wished to secure her northwestern border.”

Etruscan Threat to Nepete and Sutrium (386 BC)

As the Romans advanced into southern Etruria, the strategically-located centres of Nepete and Sutrium, which enjoyed the protection of Rome, became the focus of Etruscan resistance. The Romans had thwarted an Etruscan attempt to take Sutrium in 389 BC (as noted above). However, the danger remained: according to Livy, in 386 BC:

“... envoys from Nepete and Sutrium arrived [in Rome], begging for help against the Etruscans ... [This well-timed alert was fortunate for Rome, since] these places, fronting Etruria, served as gates and barriers on that side [of Roman territory]: ... The Senate accordingly decided to ... undertake the war with Etruria”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 9: 3-4).

The consular tribunes, Marcus Furius Camillus and Publius Valerius Potitus Poplicola marched to Sutrium, where:

“...they found the Etruscans in possession of part of the town but quickly expelled them: Sutrium was restored ‘to our allies’ [i.e. its inhabitants]”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 9: 12).

The army continued to Nepet, but found that it had already surrendered to the Etruscans:

“... through the treachery of some of the townsfolk. ... the Etruscans were holding the walls and guarding the gates. ... [The Romans scaled the walls] and ... the town was captured. ... the Nepesines [who laid] down their arms... were ordered to be spared. The Etruscans, whether armed or not, were killed, and those Nepesines who had [effected the surrender to the Etruscans] were beheaded; the people who had had no share in [the surrender to the Etruscans] received their property back, and the town was left with a [Roman] garrison”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 10: 1-6).

The historical accuracy of these passages is often doubted. However, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at pp. 348-9) argued that:

“... it remains legitimate to argue that the basic notice is sound, [albeit] that some details from the fighting [at Sutrium] in 389 BC [might] have been grafted on to it.”

Colonies at Nepete and Sutrium (ca. 383 BC)

In the aftermath of the Gallic sack, the strategically-located centres of Nepete and Sutrium, which enjoyed the protection of Rome, became the focus of Etruscan attention. In 386 BC, Sutrium came under attack from the Etruscans and Nepete actually surrendered to them, although a Roman army soon recovered it. At sometime shortly thereafter, the Romans (either alone or in conjunction with the Latin League) founded colonies in both locations: Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 347) observed that, although Livy’s account of the surrender of Falerii in 394 BC (above):

“... may be an exaggeration, Rome certainly [confiscated] land from Falerii upon which the Latin colonies of Nepete and Sutrium were later established.”

The reason for the foundation of these colonies was clearly strategic: as Livy had observed (in the context of the threat to them in 386 BC:

“... these places face Etruria, serving as gates[from one side] and barriers on [the other, so that]:

✴the Etruscans were anxious to seize them whenever they were planning ing hostilities; whilst

✴the Romans were equally anxious to recover and hold them”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 9: 4).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 347) noted that the foundation of these colonies:

“... gave [Rome] control of the area between the Tiber and the Ciminian Mountain ... .”

There is some uncertainty as to the dates of these foundations:

✴According to Livy, who does not mention the colonisation of Sutrium:

“[In 383 BC, three] commissioners were appointed to settle a colony at Nepete”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 21: 4).

✴According to Velleius Paterculus:

“Seven years after the capture of [Rome] by the Gauls [i.e., in 383 BC], a colony was founded at Sutrium ... another [was founded] after an interval of [10] years [i.e., in 380 BC] at Nepete”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 14: 2).

Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, pp. 298-9, entry 1) suggested that both colonies were established in 383 BC. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 571) suggested that, on balance, one should:

“... reject the testimony of Velleius [which implies broad acceptance of Livy’s testimony] for the date of the colonisation of Nepete and profess agnosticism as to when Sutrium was colonised.”

However, he acknowledged (at p. 341) that both were colonised in the early 4th century BC and concluded (at p. 349) that:

“... the victories of [the dictator M. Furius] Camillus, both before and after the Gallic sack [of Rome in ca. 390 BC], gained Rome control of southern Etruria, and her dominion was secured by the foundation of colonies at Sutrium and Nepete.”

Political Settlement in Southern Etruria (396 - 383 BC)

I describe the details of the settlements by which Rome consolidated its position in southern Etruria during this period in my page on Political Settlement in Etruria: (396 - 265 BC). In summary:

✴in 393 BC, viritane citizen settlement began on land that had been confiscated from Veii;

✴in 390 BC, the people of Caere were granted hospitium publicum (a covenant of hospitality);

✴in 389 BC, those Veientians, Capenatians, and Faliscans that had remained loyal to Rome were granted citizenship (probably with voting rights);

✴in 387 BC, four new voting tribes (the Stellatina; the Tromentina; the Sabatina; and the Arnensis) were added for the citizens of this region, which took the total number to 25; and

✴in ca. 383 BC, colonies were founded at Nepete and Sutrium, probably on land that had been confiscated from Falerii a decade or so earlier.

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 349) pointed out (at p. 349) that:

“... the victories of Camillus [in this period] gained control of southern Etruria for Rome, and her dominion was secured by the foundation of colonies at Sutrium and Nepete.”

He also noted (at p. 347) that these foundations:

“... gave [Rome] control of the area between the Tiber and the Ciminian Mountain ... .”

The effectiveness of these measures are evidenced by the fact that there is no record of further hostilities between the Romans and the Etruscans until 358 BC.

Volscians (388 - 382 BC)

Adapted from K. Walsh et al., referenced below, 2014, Figure 1, p. 31)

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 333) noted that the Volscians had overrun a number of places in the Latin plain south of Rome in the 5th century, notably: Antium; Circeii; Cora; Satricum; Tarracina; and Velitrae. He also noted (at p. 347) that, according to Diodorus Siculus, the Romans had begun to make inroads here before the Gallic sack:

✴at Velitrae in 404 BC (‘Library of History’, 14: 34: 7); and

✴at Circeii, in 393 BC (‘Library of History’, 14: 102: 4).

Roman Penetration of the Ager Pomptinus (388 - 382 BC)

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 349) argued that Camillus’ victory over the Volscians in 389 BC after:

“... the battle ad Maecium [above] was decisive in allowing Rome to continue her penetration of [the Pomptine territory to the south of it].”

He noted (at p. 434) that this territory was made up of:

“... the dry land between [the coastal marshes] and the [Lepine Mountains]: that is, the territory of Norba, Setia and Circeii.”

This region is described in detail in the paper by Kevin Walsh, Peter Attema and Tymon de Haas (referenced below). The first evidence of this attempted Roman expansion here is in 388-7 BC, when (as described in my page Political Settlement I (396 - 358 BC)) the authorities in Rome tried somewhat unsuccessfully to interest the plebeians in the prospect of viritane settlement there. The reluctance of the potential citizen settlers is understandable in view of the continuing hostility of Volscians and Latins alike.

Revolt of the Volscians and Latins in 386 BC

The dangers became manifest in 386 BC, when, according to Livy:

“... [Roman] anxiety was diverted from the Etruscan war [above] by the arrival in the city of a body of fugitives [presumably Roman settlers] from the ager Pomptinus, who reported that the people of [the Volscian centre at] Antium were in arms, and that the Latins had sent an army to assist them. ... The Senate thanked Heaven that Camillus was [one of the six serving military tribunes, and they selected him to prosecute the war]”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 6: 4-8).

With these formalities in place:

“... Camillus proceeded to Satricum, where the Antiates had assembled, not only Volscian troops , ... but also an immense body of Latins and Hernicans ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 7: 1).

When a sudden storm ended a day of fierce fighting:

“... the Latins and Hernicans left the Volscians to their fate and started for home ... When the Volscians found themselves thus deserted ... they abandoned their camp and shut themselves up in Satricum. [When Camillus stormed Satricum], the Volscians threw away their arms and surrendered”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 8: 8-10).

Camillus was now intent upon taking:

“... Antium, caput Volscorum (the capital of the Volscians) and the starting point of the [latest] war ... [He therefore] went to Rome to urge upon the Senate the necessity of destroying Antium. [However]. in the middle of his speech ... , envoys arrived from Nepete and Sutrium begging for help against the Etruscans and pointing out that the chance of rendering assistance would soon be lost. Fortune [thus] diverted Camillus' energies away from Antium ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 8: 8-10).

Dictatorship of Aulus Cornelius Cossus (385 BC)

According to Livy, in 385 BC:

“... a serious war broke out, and a still more serious disturbance at home:

✴the Volscians started the war, aided by the rebellious Latins and Hernici; while

✴the domestic trouble arose in a quarter from which it was least expected: from Marcus Manlius Capitolinus, a man of patrician birth and brilliant reputation”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 11: 1-2).

In these circumstances, it was necessary:

“... to arm the government with stronger powers. The Volscian war, which was serious enough, was made much more so by the defection of the Latins and Hernici, and this was put forward as the ostensible reason [for Senate’s action]. It was, however, the revolutionary designs of Manlius that mainly decided the Senate to nominate a dictator: A. Cornelius Cossus was nominated and he named T. Quinctius Capitolinus as his master of the horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 11: 9).

I discuss the sedition in my page Sedition of M. Manlius Capitolinus and its Aftermath (385 - 377 BC).

Before dealing with Manlius, Cornelius marched into the ager Pomptinus, which had been invaded by:

“... an immense Volscian army (in spite of their having been so lately crippled by the successes of Camillus). Their numbers were increased by Latins and Hernici, as well as by a body of men from Circeii, and even by a contingent from Velitrae, where there was a Roman colony”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 12: 6).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at pp. 507-8) pointed out that, according to the surviving sources, Circeii and Velitrae were both colonies of Rome (presumably in conjunction with Latin League) at this time, having been re-founded as such in 404 and 393 BC respectively. As we shall see, Livy also proceeded on this assumption later in his account. This ‘immense’ and disparate army was duly routed, after which:

“The flight and pursuit [of enemy soldiers] continued until nightfall. ... The majority of the [prisoners of war] belonged to the Hernici and Latins, .... Some were also recognised as belonging to Circeii and to the colony at Velitrae. They were all sent to Rome and examined by the leaders of the Senate. ... [to whom they] disclosed ... the defection of their respective nations”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 13: 6-8).

Livy recorded that Cornelius:

“... kept his army permanently encamped [in the ager Pomtinus], fully expecting that the Senate would declare war against these peoples. [However], much greater trouble at Rome itself necessitated his recall [to the city]”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 14: 1).

Later in his account, Livy noted that Cornelius:

“... celebrated his triumph over the Volscians ... , (‘History of Rome’, 6: 16: 5; note that this website gives 6: 15: 12).

Unfortunately, the entries in the fasti Triumphales at this time no longer survive.

Renewal of War (383-2 BC)

Livy recorded direct hostilities between Rome and Praeneste in 383 BC (see below). In response, in 382 BC:

“The Praenestines joined forces with the Volscians and in the following year took the Roman colony of Satricum by storm ... This incident exasperated the Romans, [who consequently elected] Marcus Furius Camillus as consular tribune for the 6th time”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 22: 3-4).

After a long and probably invented account of the internal politics within the Roman army, Livy recorded that the Volscians were finally ejected (‘History of Rome’, 6: 22: 11). Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 628) suggested that this Roman success might be related to a record of Velleius Paterculus, that:

“[Eight] years after the capture of Rome by the Gauls [i.e. in 382 BC ], a colony was founded at Setia”, (‘Roman History’, 1: 14: 2).

This colony was some 30 km west of Satricum, on the edge of Volscian territory, and it is possible that it was founded on land that fell into Roman hands at this time.

Latium (383 - 379 BC)

White dots:( Vitellia, Labicum, Signia, Velitrae, Norba, Ardea, Circeii) = colonies founded in 500 - 390 BC)

Red dots:(Satricum, Setia) = colonies founded in 390 -358 BC)

Red asterisk (Tusculum) = Latin city incorporated into the Roman state (in 381 BC)

Bold italics (Praeneste, Tusculum, Lanuvium, Velitrae, Circeii) = centres identified as recalcitrant in 389 - 358 BC

Adapted from Linguistic Landscape of Central Italy

As noted above, Livy reported that, when the Gallic crisis receded, the Romans:

“... were not ...long left undisturbed: ... still further alarm was created by the defection of the Latins and Hernicans [in 389 BC], [despite the fact that] these nations had never wavered in their loyal friendship with Rome ... [since] the battle of Lake Regillus [in ca. 500 BC]”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 2: 3).

Earlier History

In the case of the Latins, this peace had been agreed after battle of Lake Regillus in a treaty, the foedus Cassianum, which was named for Spurius Cassius Viscellinus, the consul of 493 BC. According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, its most important provisions were as follows:

"Let there be peace between the Romans and all the Latin cities as long as the heavens and the earth shall remain where they are. Let them: neither make war upon another; nor bring in foreign enemies; nor grant a safe passage to those who shall make war upon either [party]. Let them assist one another, when warred upon, with all their forces; and let each have an equal share of the spoils and booty taken in their common wars. ... ”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 6: 95: 2).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 337) argued that, while this:

“... cannot be a literal translation of an archaic Latin document, ... what matters is whether the content [set out by Dionysius] ... was largely invented, and there is no reason to believe that it was.”

According to Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at pp. 335-6), it can be:

“... [established] beyond reasonable doubt that, in the Republican period before 338 BC, the Latins had a political league that met at [a place called] Ferentina, ... [which] was probably near Nemi and Aricia.”

It seems likely that the foedus Cassianum had been agreed between Rome and this Latin League. Oakley observed (at p. 336) that this treaty:

“... stopped the fighting between Rome and the other Latin states for over a century, and thus proved to be a turning point in her history.”

He also noted (at p. 337) that:

“A factor that may have induced both parties [to it] to have come to terms was the predatory raiding of the Aequi and the Volsci.”

Evidence for the success of the alliance included the facts that:

✴the Hernici joined it in 486 BC (see below); and

✴the allies founded a number of colonies before the Gallic sack, including at least one (Circeii) in Volscian territory.

Latins’ Response to the Gallic Sack

In the passage above, Livy identified the Gallic sack as the event that precipitated the start of the unravelling of relations between Rome and her Latin neighbours. His account suggests that the process was initially low-key: having articulated Roman concerns in 389 BC, he noted that, in 387 BC, the Senate addressed:

“... the subject of the Latin and Hernican wars ... but, owing to the concern felt about a more serious war [in Etruria, this meeting] was adjourned”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 6: 2).

As noted above, Livy recorded that some Latin cities fought with the Volsci in 386. In this year, the Romans therefore:

“... demanded satisfaction from the Latins and Hernici; they were asked why they had not furnished a contingent in accordance with the [foedus Cassianum] in recent years. ... [The reply was] to the effect that:

✴it was through no fault [of the states in question] states that some of their men had fought [without permission] in the Volscian ranks; these had paid the penalty of their folly and not a single one had returned; and

✴the reason why they had not supplied troops [to the Romans in the war with Volsci] was their [own] incessant fear of [attack by] the Volscians ...

The Senate considered that this [unsatisfactory] reply provided grounds for war, but that present time was inopportune [for such drastic action]”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 10: 6-9).

As noted above, the Romans accused ‘the Latins and Hernici, together with the colonists from Circeii and Velitrae’ of aiding the Volsci in 385 BC. Furthermore, in 383 BC, Rome was again beset by threats, not only from the Volsci, but from:

“.... the colonies of Circeii and Velitrae, who had long been meditating revolt; ... Latium, which was an object of suspicion; and also a new enemy, ... [the Latin centre of] Lanuvium, which had hitherto been a most loyal city”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 21: 2).

To make matters worse, in the same year

“... for the first time, there arose a rumour of a revolt at Praeneste [one of the largest of the Latin towns]: the people of Tusculum, Gabii, and Labicum, whose territories they had invaded, laid a formal complaint [before the Romans, albeit that] the Senate refused to believe charges that they did not wish to be true”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 21: 9).

Although Livy reported relatively little actual fighting between Rome and its Latin neighbours in this period, he was clearly of the opinion that the terms of the foedus Cassianum were increasingly ‘honoured in the breach’.

Incorporation of Tusculum (381 BC)

Livy’s first significant record of direct hostilities between Rome and a Latin centre came late in 383 BC, when:

“An engagement took place at Velitrae, where the auxiliaries from Praeneste were almost more numerous than the colonists themselves. The Romans soon won the day ... The tribunes refrained from storming Velitrae, for they were doubtful of success and did not think it right to reduce the colony to ruin. [Since] the dispatches to the Senate ... were more critical of Praeneste than of Velitrae, ... war was declared against Praeneste”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 22: 2-3).

As noted above, the people of Praeneste then assisted the Volsci to take Satricum. However, we hear no more about them in this context: instead, we hear that, when Camillus finally ejected the Volscians from Satricum in 381 BC:

“On examining the prisoners, it was discovered that some were from Tusculum; these were brought separately before the tribunes and ... admitted that their state had authorised their taking up arms. Alarmed at the prospect of a war so close to Rome, Camillus said that he would [personally] conduct the prisoners to Rome, so that the Senate might [know] that the Tusculans had abandoned the alliance with Rome. ... the Senate resolved upon war with Tusculum, and entrusted the conduct of it to Camillus. ... But, [as things turned out], there was no war with the Tusculans ... When the Romans entered their territory, ... the townsmen, came ... to meet [them] in civic attire ... [and] Camillus looked everywhere in vain for some signs of war ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 25: 1-11).

Following their complete submission, the people of Tusculum:

“... obtained peace ... and, not long after, civitatem etiam impetrauerunt (they obtained citizenship)”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 26: 8).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 358) observed that:

“It seems reasonable to assume that the incorporation was similar to the later incorporation of [other] Latin states optimo iure (with voting rights) in 338 BC.

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 357) observed that, despite the suspect elaboration of this account:

“.. we need not doubt that Tusculum was incorporated [into the Roman state] in this year, a striking testimony to the power of Rome in the aftermath of the Gallic sack. Livy interpreted this incorporation as a generous gesture on Rome’s part; ... rather, it was an aggressive act in retaliation to a [similarly] aggressive act on the part of Tusculum. ... The [real details of the] tension between [Rome and Tusculum] are now irretrievably lost, but we may assume that the incorporation [of the latter] followed a major Roman victory.”

Tusculum, which can be securely assigned to the ancient Papiria tribe, presumably received this assignation at this time. Daniel Gargola (referenced below, map 4, at p. 95) suggested that this voting district had originally extended towards Tusculum, and it seems likely (at least, to me) that, after the incorporation of Tusculum and its erstwhile territory, it now extended as a continuous tract of Roman territory towards the Alban Mount. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 357) observed that, after this incorporation:

“... the ager Romanus [ran] continuously from Veii ... to Tusculum ...”

War with Praeneste (381 - 379 BC)

As noted above, Rome declared war on Praeneste in 381 BC. Livy returned to this war in 380 BC, when:

“A report reached Praeneste that no army had been raised in Rome [because of internal problems], that no commander-in-chief had been selected, and that the patricians and plebeians had turned against one another. Seizing the opportunity, their generals led their army by rapid marches ... [as far as] the Colline Gate. There was wide-spread alarm in Rome, and ... T. Quinctius Cincinnatus [was consequently appointed] as dictator”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 28: 1-3).

The elaborate detail in Livy’s account of the fighting that followed can be safely discounted. The result was apparently that the Praenestine forces:

“... shut themselves in Praeneste, feeling hardly safe even behind its walls. Eight towns under the jurisdiction of Praeneste were successively attacked and reduced without much fighting. Then the army advanced against Velitrae, which was successfully stormed. Finally, [the Romans] arrived at Praeneste, ... [which] was captured, not by assault, but after surrender. Quinctius returned to Rome [in triumph]”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 29: 6-8).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 358) observed that:

“... there can be no doubt that [Rome’s] position in Latium was immeasurably strengthened by the campaigns of 380 BC. It may even be [true]... that she captured Velitrae, as Livy suggests, since ... [we do not] hear of fighting there [again until 369 BC, see below].”

In 379 BC, Livy mentioned:

“.. the renewal of hostilities by the Praenestines, who had stirred up the Latin peoples”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 30: 8).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 358) observed that:

“We do not know how extensive the fighting was, though it may have been Praeneste’s final and ineffectual gesture: she is not mentioned again until 358 BC [see below].”

Latium after the Gallic Sack: Conclusions

In the extracts above, Livy describes a progressive deterioration in the relations between Rome and her Latin ‘allies’ in the two decades or so after the Gallic sack. However, by the end of the period, little had actually changed ‘on the ground’:

✴Roman territory now extended to and encompassed Tusculum, whose inhabitants were now Roman citizens; and

✴two new colonies had been founded on of near what had been Volscian territory: at Satricum (in 385 BC); and at Setia (in 382 BC, reinforced in 379 BC).

Wars with the Volsci and Latins (377 - 367 BC)

Destruction of Satricum (377 BC)

According to Livy, in 377 BC:

“... the Latins and Volscians ... united their forces and camped at Satricum. ... [Two of the consular tribunes], Publius Valerius Potitus Publicola and Lucius Aemilius Mamercinus , [led an army to] Satricum, [where] they found the enemy drawn up for battle ... and immediately engaged him. ... [After three days of fighting], the Roman attack became irresistible ... [and the enemy] camp was taken and plundered. The following night, [the enemy] evacuated Satricum and ... [took refuge in] Antium ... Some days were spent in harrying the country , since the Romans were not sufficiently provided with military engines for attacking the walls, and the enemy was not disposed to run the risk of a battle”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 32: 4-11).

The enemy alliance at Antium began to crumble, and:

“The Latins took their departure and so dissociated themselves from a [prospective] peace that they considered dishonourable. The Antiates ... [then] surrendered their city and territory to the Romans”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 33: 3).

Livy then recorded that:

“The exasperation and rage of the [departing] Latins ... rose to such a pitch that they set fire to Satricum, which had been their first shelter after their defeat: ... not a single roof of that city escaped, except the temple of Mater Matuta”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 33: 4).

They then:

“... attacked Tusculum, in revenge for its having deserted the communi concilio Latinorum (national council of the Latins) and ... even accepting her citizenship. ... [Tusculum] was taken at the first alarm, with the exception of the citadel, to which the townsmen fled for refuge ... With the alacrity that the honour of the Roman people demanded, an army was marched to Tusculum under the command of [another two of] the consular tribunes, Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus and Servius Sulpicius Praetextatus. ... [The Romans forced entry into the city while the people of Tusculum attacked from the citadel]. The double attack ... left the Latins with no strength to fight and no room for escape: ... they were killed to a man”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 33: 6-12).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 359) observed that:

“This bizarre tales baffles both explanation and refutation, though we may reasonably hold that most of the details of the fighting at Satricum are invented. It seems plausible, however, to argue that the [subsequent] attack on Tusculum was occasioned, [as Livy claimed], by Latin resentment about her loss to the league ...”

Siege of Velitrae (370 - 367 BC)

Livy recorded that, in 370 BC, the Romans enjoyed:

“... a respite from foreign war. [However], the colonists of Velitrae ... made various incursions into Roman territory and began an attack on Tusculum. The citizens there, old Roman allies and now citizens, implored help [from Rome] ... [Since the political situation at Rome was difficult], it was only after a very great struggle that an army was raised. It dislodged the enemy army from Tusculum and forced it to take refuge behind its own walls”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 36: 1-4).

The Romans now laid siege to Velitrae, but seem to have recalled their army at the start of 368 BC (‘History of Rome’, 6: 38: 1). Livy the noted that, in 367 BC:

“With the exception of the siege of Velitrae, in which the result was delayed [by the political impasse in Rome], albeit inevitable, Rome was quiet”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 42: 4).

Although Livy did not record when Velitrae finally fell, Plutarch did: he noted that Camillus’ victory over the Gauls near the Alban Mount in 367 BC (see below):

“... was [his] last military exploit ..., for [his subsequent recovery] of Velitrae was a direct sequel of this campaign, and [he secured it] without a struggle,” (‘Life of Camillus’, 42: 1).

As we shall see below, he was referring to the events of Camillus’ 5th dictatorship in 367 BC.

Gallic Raid of 367 BC ?

Livy recorded that, in 367 BC:

“Rome was suddenly startled by rumours of the hostile advance of the Gauls. Marcus Furius Camillus was [consequently] nominated dictator for the 5th time ... :

✴[Quintus Claudius Quadrigarius] is our authority for the statement that a battle was fought with the Gauls at the river Anio this year, and that it was on this occasion that the famous fight took place on the bridge, in which T. Manlius killed a Gaul who had challenged him and despoiled [the unfortunate Gaul] of his golden collar in the sight of both armies. I am more inclined to believe, with the majority of authors, that these events took place [in 361 BC - see below].

✴However, Camillus did fight a pitched battle against the Gauls in 367 BC, in the ager Albanus”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 42: 4-8).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 720) located the ager Albanus on the sloped of the Mons Albanus (Alban Mount). Thus, if this raid actually did take place, then it occurred close to Tusculum, which had been incorporated into the Roman state in 381 BC (see above). In other words, it would have been very reminiscent of the earlier, catastrophic Gallic raid on Rome. This point was inevitably not lost on Livy, who noted that:

“Although the Romans felt a great dread of the Gauls, bearing in mind their former defeat [in 389 BC], victory [in 367 BC] was neither doubtful nor difficult. Many thousands of the barbarians were slain ... Many others [fled], mainly in the direction of Apulia ... By the joint consent of the Senate and plebs, a triumph was decreed to Camillus”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 42: 4-8).

It is likely that a fragmentary entry in the fasti Triumphales for 367 BC related to this triumph.

Plutarch (who located this battle on the Anio) gave an otherwise similar (albeit embellished) account. He too stressed that Camillus’ victory was easily won:

“Just before dawn, he led his men down into the plain and drew them up in battle-array ... The Barbarians now saw [that they were not] the few and timid men that they had expected ... It was this [realisation that first] shattered the confidence of the Gauls”, (‘Life of Camillus’, 41: 1-3).

Having thus shaken the Gauls, the Romans easily crushed them. Plutarch ended his account by observing that:

“This battle was, they say, fought 13 years after the [Gallic] capture of Rome ... [Since then, the Romans] had mightily feared [the Gauls] ... So great had been their terror that they made a law exempting priests from military service, except in case of a Gallic war”, (‘Life of Camillus’, 41: 6).

He then noted that:

“This was the last military exploit performed by Camillus ...”, (‘Life of Camillus’, 42: 1)

As noted above, Plutarch observed that Camillus subsequently recovered Velitrae without a struggle.

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 364) argued that:

“... strong suspicions must attach to Camillus’ alleged victory in 367 BC: it is wildly exaggerated by Plutarch ..., and the whole event may have been invented to give the great man one last victory over the Gauls ... On the other hand, it is not absolutely incredible that the Romans fought the Gauls in this year ...”

He referenced Livy’s claim that, in 366 BC:

“... the Gauls were rumoured ... to have regrouped in Apulia”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 9);

and conceded that this:

“... is precisely the kind of notice one would expect if there had been a band of Gauls on the loose is southern Italy.”

However, notwithstanding this circumstantial support for the putative Gallic raid of 367 BC, he concluded that:

“It is best to remain undecided on [its authenticity], though inclined to scepticism.”

Plague Years (365 - 363 BC)

Death of Camillus (365 BC)

Livy recorded that, in the consulship of L. Genucius and Q. Servilius (365 BC):

“Matters were quiet as regards both domestic troubles and foreign wars but ... a pestilence broke ... The most illustrious victim was M. Furius Camillus, whose death, though occurring in ripe old age, was bitterly lamented. He had been ... a truly exceptional man in every change of fortune:

✴before he went into exile, he was foremost in peace and war;

✴he was rendered still more illustrious when actually in exile, by the regret that the State felt for his loss, and the eagerness with which, after [the Gallic invasion of Rome], it implored his assistance; and

✴equally, after being restored to his country, by the success with which he restored its fortunes, together with his own.

For 25 years thereafter, he lived up to his reputation, and was counted worthy to be named, next to Romulus, as the second founder of the City”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 1: 8-10).

Consuls of 364 BC

Livy recorded that:

‘... the pestilence continued throughout [364 BC]. The new consuls were C. Sulpicius Peticus and C. Licinius Stolo. Nothing worth mentioning took place, except for [a series of measures that were designed to propitiate the gods, none of which was successful]”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 2: 1).

The fasti Capitolini record the consuls of this year as [C. Sulpicius] Peticus and C. Licinius Calvus. For the reasons discussed above, it is probably now impossible to deduce whether this C. Licinus was Stolo or Calvus. For further discussion of this point, see the section below on the consuls of 361 BC.

Dictator Clavi Figendi Causa (363 BC)

The plague continued into363 BC, when, according to Livy:

“Owing to an inundation of the Tiber, the Circus was flooded in the middle of the Games, and this produced an unspeakable dread; it seemed as though the gods had turned their faces from men and despised all that was done to propitiate their wrath. C. Genucius and L. Aemilius Mamercus were the new consuls, each for the second time”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 2-4).

As desperation took hold:

“Older men are said to have remembered that a pestilence had once been assuaged by the dictator hammering in a nail. The Senate believed this to be a religious obligation, and ordered the appointment of a dictator clavi figendi causa (for the purpose of fixing the nail) ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 4-6).

I discuss the nature of this dictatorship in my page on the Dictatorship Clavi Figendi Causa: in short, dictators of this kind were appointed in 363 BC and on at least three later occasions, for the purpose of presiding over a ritual of propitiation of the gods that involved the ‘fixing’ of a sacred nail.

According to Livy, after the Senate had decided on the appointment of a dictator clavi figendi causa in 363 BC:

“... Lucius Manlius was accordingly nominated, and he appointed Lucius Pinarius as his master of the horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 8).

This is confirmed by a fragmentary record for this year in the fasti Capitolini, which reads:

✴[Lucius Manlius Capitolinus] Imperiosus as dicator clavi figendi caussa; and

✴[L. Pinarius] Natta as his master of horse.

In fact, Livy did not record whether Manlius actually fixed the propitiatory nail: he simply recorded that he:

“... acted as if his had been appointed for military purposes rather than for the purpose of correcting a failure in religious observance. He harboured ambitions for war with the Hernici, and angered the men liable to serve [in this war] by the oppressive way in which he conducted their conscription. [When he found himself facing] the unanimous resistance of the tribunes of the plebs, he gave way (either voluntarily or through compulsion) and laid down his dictatorship”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 9).

However, according to Livy, this resignation:

“.. did not... prevent his impeachment the following year ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 4: 1).

I discuss this putative impeachment below.

Hernician Revolt (362 - 358 BC)

Adapted from Linguistic Landscape of Central Italy

The Hernici inhabited a territory on the left bank of the Sacco river that was bounded by that of the Aequi, the Marsi and the Volsci. They used an Oscan dialect that was distinct from that of any of their neighbours, including the Latins.

Prior Events

Livy (‘History of Rome’, 2: 41: 1) recorded that they agreed a treaty with Rome in 486 BC , and Dionysius of Halicarnassus (‘Roman Antiquities’, 8: 69: 2) added that this was a copy of the foedus Cassianum. From this point, they seem to have aided the Romans and Latins in their struggle against the Aequi and the Volsci. As mentioned above, Livy began to associate the Hernici with dissident Latins on a regular basis from the time of the Gallic sack of Rome in 389 BC. However, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 3) pointed out that:

“... since he records neither a Hernician attack on Rome nor a Roman attack on the Hernician strongholds in the Sacco valley, we should probably assume that the two powers co-existed more or less peacefully in the period 389 - 367 BC.”

Events of 366 BC

Livy began his account of the Hernician revolt in 366 BC in the context of a Gallic raid on Latium in 367 BC (above): he recorded that, at the start of that year:

“... the Hernici were reported to have revolted. [However, for internal political reasons, all political business was] left in abeyance ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 1: 3-4).

It seems that the Romans were then distracted by the plague of 365-3 BC (see above). Then, as we have seen above, L. Manlius Capitolinus, who had been appointed as dictator clavi figendi causa in 363 BC, had attempted to extend his mandate in order to prosecute a war against the Hernici, but had been forced to resign.

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 4) argued that, although the notices relating to the Hernici in 366 and 363 BC:

“... are vague and imprecise, ... it is unlikely that they are annalistic inventions ..., and some trouble with the Hernici in these years probably underlies them.”

Impeachment of Lucius Manlius Capitolinus (362 BC)

According to Livy, the resignation of L. Manlius Capitolinus in 363 BC:

“.. did not... prevent his impeachment in the following year ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 4: 1).

One of the charges against him was that he had used exceptional brutality in order to conscript men to fight the Hernici. It is at this point that Manlius’ son, the future T. Manlius Torquatus, entered Livy’s narrative: he recorded a story that was already known to Cicero (‘De Officiis’, 112), in which another of the charges made against the ex-dictator was that he had cruelly exiled the young Titus from Rome for no good reason. However, far from being pleased by the news of his father’s imminent prosecution, young Titus had been:

“... indignant to find himself made the grounds for the charges against [his father] and ... determined to let gods and men see that he would rather stand by him than help his enemies”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 4: 4).

In an exemplary display of filial piety, Titus arranged a private meeting with Pomponius, in which he drew his sword and threatened to use it unless Pomponius swore that he would drop all charges against his father. As Cicero recorded:

“Constrained by the terror of the situation, Pomponius gave his oath. He reported the matter to the people, explaining why he was obliged to drop the prosecution, and withdrew his suit against Manlius. Such was the regard for the sanctity of an oath in those days”, (‘De Officiis’, 112).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 84) observed:

“The historicity of the whole tale [of the prosecution of the recently-resigned dictator] is very doubtful ... :

✴it is hard to see how so much detail could have survived from 362 BC to Livy’s time; and

✴[the putative defendant] corresponds so well to the stock character of the Manlii.”

Appointment of T. Manlius as Military Tribune (362 BC)

Livy recorded that, although the plebs would certainly have liked to have seen the ex-dictator punished, they:

“... were not displeased at [Titus’] daring deed in defence of [him], which was all the more meritorious because it showed that his father's brutality had not in any way weakened his natural affection and sense of duty. Not only was the prosecution of the father dropped, but the incident proved the means of distinction for the son: that year, for the first time, the military tribunes were elected by the popular vote, ... [and Titus] obtained the second out of six places, although he had done nothing at home or in the field to make him popular, having passed his youth [in exile] in the country, far from city life”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 4: 7-9).

Thus, the scene was set (however fictitiously) for the spectacular career of the future T. Manlius Torquatus: he earned his cognomen in a famous engagement with the Gauls in 351 BC (see below).

War with the Hernici (362 - 358 BC)

Events of 362 BC

The Romans finally declared war on the Hernici in the second consulships of Lucius Genucius Aventinensis and Quintus Servilius Ahala (362 BC). Livy noted that the conduct of the war fell to Genucius, who was:

“... the first plebeian consul to manage a war under his own auspices ... As chance would have it, when Genucius, fell into an ambush whilst making a vigorous attack upon the enemy, the legions were taken by surprise and routed. Genucius was surrounded and killed without the enemy being aware his identity”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 6: 3-6).

The Romans replaced the dead consul by a dictator, Appius Claudius Crassus, at which point, the Hernici:

“... called up omne Hernicum nomen (every man in the Hernican nation) who could bear arms: 8 cohorts were formed of 400 men each, who had been ... picked [from] the flower of their manhood ... In order to make their courage more conspicuous, [these specially-picked cohorts] occupied a special position in the fighting line”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 7: 4-6).

Clearly, Livy or his source(s) believed that the Hernici were intent upon a decisive engagement. He then gave an elaborate account of the ensuing battle, in which Romans were nearly losing heart until they finally:

“.. compelled the enemy to give ground ... [and] routed them ... They followed up the fleeing Hernici as far as their camp but abstained from attacking it, as it was late in the day. [The fighting on the second day was inconclusive but, on the following morning, the Romans] found the [enemy] camp abandoned: the Hernici had fled and left some of their wounded behind. The people of Signia saw the main body of the fugitives streaming past their walls ... and, sallying out to attack them, they scattered them in headlong flight over the fields. The victory was anything but a bloodless one for the Romans; they lost a quarter of their whole force ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 8: 3-7)

Events of 361 BC

According to Livy:

“The consuls [of 361 BC] were C. Sulpicius [Peticus] and C. Licinius Calvus”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 9: 1).

The fasti Capitolini record the consuls of this year as [C. Licinius] Stolo and C. Sulpicius Peticus (for the second time). For the reasons discussed above, it is probably now impossible to deduce whether this C. Licinus was Stolo or Calvus. As noted above, C. Sulpicius Peticus had served his first consulship in 364 BC with C. Licinius Stolo (Livy)/ C. Licinius Calvus (fasti Capitolini) as his plebeian colleague, albeit that there is no reason to think that this is anything other than coincidence. More surprising is the fact that Livy identified neither C. Licinius Stolo (his cos. 364 BC) nor C. Licinius Calvus (his cos. 361 BC) as the tribune of the plebs who had sponsored the Licinian-Sextian Laws of 367 BC.

According to Livy, the consuls of 361 BC:

“... resumed operations against the Hernici: they invaded their territory, but did not find the enemy in the open, [at which point], they attacked and captured Ferentinum, a Hernican city”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 9: 1).

The fasti Triumphales record that one of the consuls, Sulpicius, was awarded a triumph over the Hernici, presumably following this engagement. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 4) observed that:

“Ferentinum must [subsequently] have been returned to the Hernici, perhaps in the peace of 358 BC [see below], as it was ... still independent in 306 BC.”

Livy then recorded that, as the consuls:

“... were returning to Rome, the Tiburtines closed their gates against them. There had previously been numerous complaints made on both sides, but this last provocation finally decided the Romans ... to declare war against the Tiburtines”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 9: 1-2).

As we shall see below, this war was soon subsumed into a wider war with Gallic raiders in the vicinity.

Events of 360 - 358 BC

The consuls elected for this year were Caius Poetelius Libo Visolus and Marcus Fabius Ambustus. While Poetelius marched against the Tiburtines:

“... Fabius, crushed the Hernici in successive defeats, at first in comparatively unimportant actions and then finally in one great battle when the enemy attacked him in full strength. {although] Poetilius celebrated a double triumph, over the Gauls and over the Tiburtines [see below], it was considered a sufficient honour for Fabius to be allowed to enter the City in an ovation”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 9: 8-9).

The fasti Triumphales record Fabius’ ovation over the Hernici.

No fighting against the Hernici was recorded in 359 BC. According to Livy, in 358 BC, responsibility for the Hernician War was allotted to the consul Caius Plautius Proculus. He:

“... defeated the Hernici and reduced them to submission ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 15: 10-12).

The fasti Triumphales record that Caius Plautius Proculus was awarded a triumph over the Hernici. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 4) observed that:

“Whatever problems we might have with the details of Livy’s narrative, there can be no doubt that, by 358 BC, the Hernici had been subdued: Hernician wars are not mentioned again by Livy until the revolt in 307 - 306 BC.”

Gauls and Tiburtines (361 - 359 BC)

Red asterisk = site of the Roman victory over the Gauls on the Anio in 361 BC

Adapted from Linguistic Landscape of Central Italy

Dictatorship of T. Quinctius Poenus (361 BC)

Livy was aware of the appointment of a dictator at this point, although his sources disagreed about the purpose of the dictatorship:

“It is generally understood that T. Quinctius Poenus was the dictator and Ser. Cornelius Maluginensis the master of the horse:

✴According to Licinius Macer, the dictator was nominated by the consul Licinius: his colleague, Sulpicius, was anxious to get the elections over before he departed for the war, in the hope of being himself re-elected, if he were on the spot, and Licinius determined to thwart his colleague's self-seeking ambition. However, Licinius Macer's desire to appropriate the credit of this to his house, the Licinii [Calvii], lessens the weight of his authority.

✴[In view of this, and], since I find no mention of this in the older annalists, I am more inclined to believe that the immediate cause of the nomination of a dictator was it was the prospect of a Gallic war

At all events, it was in this year that the Gauls established a camp camp by the Via Salaria, at the bridge across the Anio, three miles from the City”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 9: 3-6).

As Stephen Oakley (in Timothy Cornell, referenced below, 2013, Volume III, at p. 443, F. 22) pointed out, it seems that, in the version of Licinius Macer, Licinius had nominated Quintius as dictator comitiorum habendorum cauusa (in order to hold elections). He argued (at p, 444, that the testimony of Livy’s other sources makes this unlikely. Furthermore, the fasti Capitolini followed these other sources in recording Quinctius as dictator rei gerundae caussa. Thus, the likelihood is that, since the consuls were bot campaigning against the Hernici, the arrival of these Gallic raiders did indeed prompt Quinctius’ appointment as dictator.

Single combat of T. Manlius Imperiosus Torquatus (361 BC)

Livy now set the scene for one of the most famous accounts of single combat in Roman history. Quinctius

“... marched out of the City with an immense army and fixed his camp on this side the Anio [opposite the Gallic camp on the other side of the river]. ... There were frequent skirmishes for the possession of the bridge and, [when these proved indecisive], a Gaul of extraordinary stature strode forward on to the unoccupied bridge, and ... cried:

‘Let the bravest man that Rome possesses come out and fight me, that we two may decide which people is the superior in war”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 9: 6-8).

According to Livy, the bravest of the Romans turned out to be the young and inexperienced T. Manlius Imperiosus, who (as we have seen) had been elected as one of the military tribunes in the previous year.

Livy devoted the whole of the following chapter to the ensuing fight, which reached it climax when:

“... Manlius gave two rapid thrusts in succession and stabbed the Gaul in the belly and the groin ... He left the body ... un-despoiled, with the exception of [the dead man’s] chain, which .... he placed round his own neck. Astonishment and fear kept the Gauls motionless; the Romans ... conducted [Manlius] to the dictator. In the doggerel verses that they extemporised in his honour, they called him Torquatus (adorned with a chain), and this soubriquet became a proud family name for his descendants. The dictator gave him a golden crown and, before the whole army, alluded to his victory in terms of the highest praise”, ‘History of Rome’, 7: 10: 10-14).

Livy attributed the Gaul’s withdrawal entirely to Manlius’ achievement:

“Strange to relate that single combat had such a far reaching influence on the whole war that the Gauls hastily abandoned their camp and moved to the neighbourhood of Tibur. They formed an alliance ... with that city, and the Tiburtines supplied them generously with provisions. After receiving this assistance they withdrew into Campania”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 11: 1).

I discuss this clearly apocryphal story in my page on T. Manlius Imperiosus Torquatus.

Victory over Gauls and Tiburtines (360 BC)

Livy then recorded Rome’s response to the Tiburtines’ treachery: in 360 BC:

“... the consul Caius Poetelius Libo Visolus led an army ... against [them]. ... Although the Gauls had come back from Campania to assist them, it was undoubtedly the Tiburtine generals that carried out the cruel depredations in the territories of Labicum and Tusculum and in the ager Albanus”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 11: 2).

Livy noted that the Romans would have been content to leave one of the consuls in charge of a war with Tibur, but:

“... the sudden re-appearance of the Gauls required a dictator: Quintus Servilius Ahala was nominated ... [He ordered Poetelius’] army to remain [at Tibur], in order to confine the Tiburtines to their own war ... [Servilius’ own battle] against the Gauls] ... took place near the Colline Gate ... There was great slaughter on both sides, but the Gauls were eventually repulsed and fled in the direction of Tibur as though it were a Gaulish stronghold. Poetelius intercepted the straggling fugitives not far from Tibur; the townsmen there sallied out to render them assistance and they and the Gauls were driven within their gates”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 11: 3-7).

Triumphs and Ovations (360 BC)

At this point in the narrative, Livy recorded the success of the other consul, Marcus Fabius Ambustus, against the Hernici (see above). Then, rounding off the events of the year, he recorded that:

“The dictator [Servilius] passed splendid encomiums on both consuls ... and even transferred to them the credit for his own success.

✴Poetilius celebrated a double triumph over the Gauls and over the Tiburtines.

✴[However], it was considered a sufficient honour for Fabius to be allowed to enter Rome in an ovation.

The Tiburtines laughed at Poetilius' triumph, ... [since, while] a few of them had come outside their gates to watch the disordered flight of the Gauls, ... [they had quickly] retreated into their city. [They expressed surprise that] the Romans [should] deem that sort of thing worthy of a triumph”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 11: 8-11).

Tiburtine Raid on Rome (359 BC)

Livy then recorded an odd postscript to the war: in 359 BC:

“... an army from Tibur marched against Rome in the early hours of the night ... [This caused some panic but], when the early dawn revealed a comparatively small force before the walls and the enemy turned out to be none other than the Tiburtines, the consuls decided upon an immediate attack. They issued from two separate gates and attacked the Tiburtines ... on both flanks. [Their easy defeat revealed] that they had been trusting more to the chances of a surprise than to their own courage ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 12: 1-4).

Tiburtines and Gauls (361-59 BC): Conclusions

In Livy’s account of these events, Tibur alone was of little concern to the Romans,, but their interaction with ‘the Gauls’ in this period could not be ignored. As we shall see, tGallic raiders also featured in Livy’s account of a war with nearby Praeneste in 358 BC. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 363) suggested that the Gauls in question were:

“... a warrior band, who were ... [based in] southern Italy ... and who raided Rome and Latium from the south.”

If so, then we might reasonably see these Gallic raids as opportunist, and that the Gauls who took part in them offered themselves as mercenaries to dissident Latins. Tibur and Praeneste would have been obvious takers of their mercenary services: Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 356) observed that, by the 4th century BC, they:

“... were the largest Latin towns and the ones best able to challenge Rome.”

He also argued (in 1998, at p. 6) that later events suggest that (despite Livy’s silence), Praeneste supported Tibur against Rome in the period under discussion here. Indeed, he argued that they were both:

“... at war with Rome from 361 to 354 BC.”

Read more:

D. Gargola, “The Shape of the Roman Order: the Republic and its Spaces”, (2017) Chapel Hill, North Carolina

K. Walsh, P. Attema and T. de Haas, “The Pontine Marshes (Central Italy): a Case Study

in Wetland Historical Ecology”, BABESCH, 89 (2014) 27-46

T. Cornell (ed.), “The Fragments of the Roman Historians”, (2013) Oxford

S. Roselaar, “Public Land in the Roman Republic: A Social and Economic History of Ager Publicus in Italy, 396 - 89 BC”, (2010) Oxford

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume II: Books VII and VIII”, (1998) Oxford

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume I: Book VI”, 1997 (Oxford)

T. Cornell, “The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (ca. 1000-264 BC)”, (1995) London and New York

L. Ross Taylor, “The Voting Districts of the Roman Republic: The 35 Urban and Rural Tribes”, (1960) Rome

Return to Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)