Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temple of Apollo in Circo (431 BC)

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temple of Apollo in Circo (431 BC)

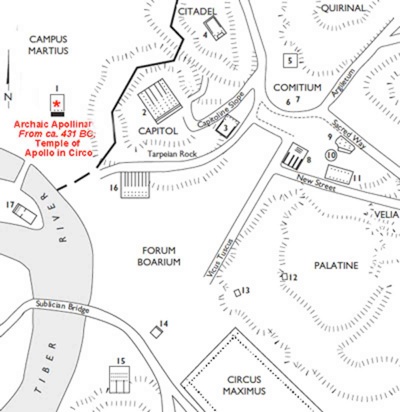

Archaic Apollinar

Rome in the early Republic

Adapted from Valerie Warrior, p. xl, my addition in red

The originally Greek cult of Apollo was introduced to Rome before 449 BC, when Livy recorded a meeting of the Senate at his shrine. He noted that the consuls L. Valerius Poplicola and M. Horatius Barbatus, who had secured important victories over the Aequi and the Sabines respectively:

“... had arranged to approach the City on the same two days [and had] summoned the Senate to the Campus Martius. When they were reporting their achievements, the leading senators complained that the meeting was being deliberately held in the midst of the soldiers in order to intimidate the senators. And so, the consuls, in order to allow no scope for accusation, moved the meeting to the prata Flaminia (Flaminian Meadows, later the Circus Flaminius), where the temple of Apollo (which was then called Apollinare) now stands”, (‘History of Rome’, 3: 63: 3).

This cult site was probably a small shrine that had been established outside the pomerium because it was dedicated to a foreign cult.

The tension evident in Livy’s account apparently arose because Valerius and Horatius, who had sponsored the pro-plebeian Leges Valeriae Horatiae before leaving for their respective provinciae, now had popular support for their requests for triumphs. As Valerie Warrior (referenced below, at p. 241, note 131) pointed out, their agreement to the re-location of the meeting to the prata Flaminia:

“... was probably a compromise, since the location was [still] outside the pomerium, which meant that the consuls could retain their miltary command], but nearer the City than the original Campus Martius. The Senate had clearly decided not to grant a triumph to either man.”

If so, then the compromise did not have the desired effect: as Livy pointed out, the upshot was that:

“... for the first time [in the history of the Republic], a triumph was celebrated at the bidding of the people, without the authorisation of the Senate”, (‘History of Rome’, 3: 63: 3).

Temple of Apollo ‘in Circo’ (ca. 433-1 BC)

Livy recorded that, in 433 BC:

“... pestilence [at least] gave a respite from [the recent political problems at Rome]. A temple was vowed to Apollo pro valetudine populi (for the the health of the people). On the advice of the [Sibylline] Books, the duoviri [Sacris Facundis] did many things to placate the anger of the gods and ward off the plague from the people. Nevertheless, a great disaster was sustained in both the City and countryside, as men and cattle perished indiscriminately”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 25: 3).

As Eric Orlin (referenced below, at p. 98) pointer out, it is not clear that the vowing of this temple was the result of the consultation of the Sibylline Books. However, we can certainly assume (with Adam Ziolkowski, referenced below, at p. 237) that this temple was:

“... [a] communal foundation par excellence.”

Livy recorded that the temple was dedicated in 431 BC:

“... by [the consul C. or Cn.] Julius Mento in the absence of his colleague, [T. Quinctius Cincinnatus], and without drawing lots. Quinctius ... complained about this to the Senate when he ... returned to the City, but to no effect”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 29: 7 - see 4: 26: 2 for Julius’ cognomen).

It seems that, since neither Julius nor Quinctius had any particular association with the temple, the Senate chose Julius to dedicate it simple because he was closer to hand at the time.

Howard Scullard (referenced below, at p. 164) noted that, on 13th July:

“... the chief day of the ludi Apollinares [see below], a sacrifice to Apollo is mentioned by the fasti Antiates maiores alone among the [surviving] calendars. The reference may be to the oldest temple of Apollo, which was dedicated on account of a plague in 431 BC ... ”

Location of the Temple

Cicero referred to a temple of Apollo in a speech of 64 BC (in which he attacked his opponents in the consular elections of the following year). The speech is now lost, but Q. Asconius Pedianus (in his commentary on this passage, search on ‘Apollo’) explained that the temple to which Cicero referred:

“... was not the temple of Apollo on the Palatine, for that was erected by [Octavian, who became the Emperor Augustus in 27 BC. The] temple [to which Cicero referred] was the one outside the Porta Carmentalis, between the Forum Holitorium and the Circus Flaminius. This was the only temple of Apollo at Rome at this time.”

This location is confirmed by the testimony of Augustus, who recorded that:

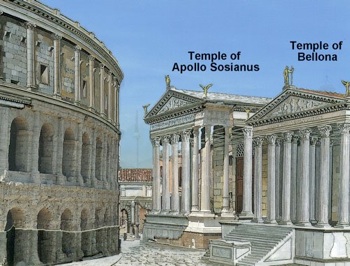

“I built the theatre that was to bear the name of my son-in‑law, M. Marcellus, near the temple of Apollo”, (‘Res Gestae’, 21).

According to Borden Painter (referenced below, at p. 10), before this area was cleared in 1926 in order to reveal its Roman monuments, including the Theatre of Marcellus:

“... small shops filled [the theatre’s] arches, and the ground level was several feet above the original. It faced the Piazza Montanara, a busy market ... [that] stood on the same spot as the ancient olive oil market [i.e., the Forum Holitorium], next to the Tiber ... Adjacent to it stood columns from the temple of Apollo, [which had been rebuilt] in 32 BC [see below].”

He also noted that the church of Santa Rita, which stood in Piazza Aracoeli at this time, was:

“... carefully disassembled for future reconstruction. The reconstruction began in 1938 next to the by-then liberated Theatre of Marcellus, at the entrance to the Piazza Campitelli.”

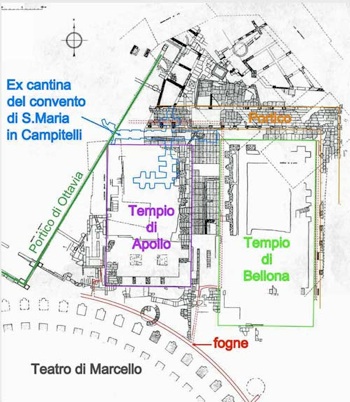

Excavations in 1932-33 and 1937-8 unearthed the podium of the original temple of Apollo and that of the temple that replaced it in the late 1st century BC (see below). The latter remains included the three Corinthian columns and their intricately carve architrave (illustrated at the top of the page) that had been rebuilt on the podium, although probably not in their original positions. A podium immediately to the east, which belonged to what was subsequently identified as the temple of Bellona (see my page on the Temple of Bellona)), was partly covered in 1938 by the reconstructed church of Santa Rita.

Restoration in 353 BC (?)

Livy recorded that, in 353 BC:

“After the return of the legions [from Faliscan territory], the rest of the year was spent in repairing the walls and towers [of Rome]. The temple of Apollo was also dedicated”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 20: 39).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 209) observed that:

“... unless Asconius [above] was gravely mistaken [when he recorded that there was still only one temple of Apollo in Rome in 64 BC], Livy ought to have referred here to [the] rebuilding and subsequent rededication [of the temple].”

Ludi Apollinares (212 BC)

According to Livy, an oracle that was discovered in 213 BC, when Hannibal still occupied much os southern Italy during the Second Punic War, declared:

“Romans, if you wish to expel the enemy ... , I advise, that games should be vowed ... to Apollo ... [and] that the [Urban Praetor] should preside in the celebration of these games”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 12: 9-10).

Livy observed that:

“This is the origin of the ludi Apollinares, which were vowed and celebrated in order to secure victory, not health, as is commonly supposed”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 12: 15).

This is the first time in the surviving sources that Apollo is associated with victory.

P. Cornelius Sulla, the Urban Praetor of 212 BC, duly presided at the first ludi Apollinares at the Circus Maximus in 212 BC. Livy subsequently recorded that, from that time:

“... all the successive Urban Praetors had conducted them, albeit that, [initially], they vowed them for a single year and did not conduct them on a fixed date. [However, in 208 BC], a serious epidemic fell upon the city ..., on account of [which], ... P. Licinius Varus, the Urban Praetor, was ordered to propose to the people a bill that those games should be vowed in perpetuity for a fixed date. He himself was the first to vow them in those terms, and he conducted them on [13th July]. From this point, that day was kept as a regular holiday”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 23: 7).

Howard Scullard (referenced below, at p. 16o) noted that:

“These annual Games became so popular that the time devoted to them was gradually extended backwards from 13 July, so that, by the end of the Republic, they occupied no less than eight days (6-13th July).”

He noted (at p. 164) that:

“Of the eight days, two were given to Circus Games [presumably still in the Circus Maximus], the others to stage productions [known as ludi scaenici].”

A passage in Plutarch’s ‘Life of Cicero’ allows us to associate Lepidus’ theatre [above] with the ludi Apollinares, albeit that the necessary reasoning is slightly tortuous. The passage in question is as follows:

“M. [Roscius] Otho was the first to separate ... the equites from the rest of the citizens. When he ... was praetor [in 63 BC], he gave them their own place at the ludi scaenici, which they still retain. The people took this as a mark of dishonour to themselves and, when Otho appeared in the theatre [in 63 BC], they hissed him insultingly, while the knights received him with loud applause ... [Things escalated, and a riot broke out] in the theatre. When [the consul] Cicero heard of this, he came and summoned the people to the temple of Bellona ...”, (‘Life of Cicero’, 13: 2-4).

Peter Wiseman (referenced below, at p. 15, citing Filippo Coarelli, referenced below, whose work I have been unable to consult directly) argued that:

“Only the ludi Apollinares were given by a praetor, the others all being the responsibility of the aediles.”

Thus, the riot of 63 BC almost certainly took place during the ludi Apollinares. Wiseman also also pointed out (citing John Hanson, referenced below, at pp. 9-25) that:

“... each temporary theatre erected for ludi scaenici under the Republic was placed in as close a topographical connection as possible with the temple of the deity in whose honour the festival was given.”

Thus, we can reasonably assume that Lepidus’ theatrum et proscaenium ad Apollinis was erected on the site of the later Theatre of Marcellus: indeed Peter Wiseman (referenced below, at p. 15) argued that the temporary theatres that were used for the ludi Apollinares were erected:

“... in front of the only ... temple [of Apollo] in Rome, on the site where, for that very reason, the stone theatre of Marcellus was later built.”

He pointed out (at p. 17) that this must have been the site of the riot of 63 BC discussed above. He also argued (again following Filippo Coarelli) that:

“The steps of the temple [of Bellona], from which Cicero must have delivered his speech [to the rioters] must commanded that part of the open area of the Circus Flaminius that was nearest to Apollo's temple and to the wooden theatre . The conclusion is inescapable: the ... unidentified temple [that had been excavated in the 1930s immediately to the east of the temple of] Apollo must [have been the temple of Bellona].”

Colonnade and the Theatre ‘ad Apollinis’ (179 BC)

Probable appearance of the site after the completion of the Theatre of Marcellus in 13 AD

published by Larry Koester on Flickr

According to Livy, in 179 BC, the censor M. Aemilius Lepidus:

“... contracted for the building of theatrum et proscaenium ad Apollinis (the seating area and stage of a theatre at the temple of Apollo)”, (‘History of Rome’, 40: 51: 3);

and his colleague, M. Fulvius Nobilior:

“... put out for contract a larger number of works, ... [including a] colonnade ... at the temple of Apollo Medicus”, (‘History of Rome’, 40: 51: 3-5).

Thus, at least by 179 BC, the original reason for the construction of the temple was reflected in the epithet ‘Medicus’.

Constance Campbell (referenced below) pointed out that Lepidus’ structure is one of three possibly-permanent theatres recorded in the our surviving sources that were commissioned in the 2nd century BC. She concluded (at pp. 77-8) that:

“The earliest of the three theatres, the one at the Temple of Apollo, is the most problematic of the three. It was almost definitely [intended] to be built on completely level ground, either at the site of the later Theatre of Marcellus or further out in the Campus Martius. There is no trace of this theatre, either in literary references other than the passage from Livy [above] or in physical remains ... If, as is likely, it was to be built at or near the site of the later Theatre of Marcellus, then it was certainly not in existence in the middle of the 1st century BC, when Julius Caesar determined to build a theatre at this site [see below]: we know from Cassius Dio that Caesar had to buy up a certain amount of private property and demolish the houses and temples standing on [the site] in order to have space for his theatre.”

She observed that:

“[It] is quite likely [that [Aemilius’ theatre had nor been intended to be permanent]: 179 BC is very early for an attempt at a free standing permanent theatre.”

Furthermore, even if it had been built as a permanent theatre:

“... it is at least possible that ... the Romans did not have good enough concrete to build a free-standing theatre at this time, and that it was either abandoned [during construction] or destroyed [within a short space of time]. “

The important point for our purposes is that, as John Hanson (referenced below, at p. 18) pointed out, whatever was the duration of this theatre:

“... the passage [above] ... provides absolute assurance of the construction, or at least a plan for the construction, of a stage and an auditorium ‘near the temple of Apollo’."

Demolition of the Temple

From M. Bianchini (referenced below) Figure 0 (not included in the version published in MEFRA

This is an elaboration of the plan published by Alessandro Viscogliosi (in a book that is now out of print)

As noted above, this area was excavated in in 1932-33 and 1937-8. The results were not published at the time, and the important book on the temple by Alessandro Viscogliosi (referenced below) is now out of print. However, Marco Bianchini (referenced below) had published an extremely useful report following further excavations in 1998 of the northern part of the area (in the ex-convent of Santa Maria in Campitelli. Bianchini concluded that the construction of the Theatre of Marcellus necessitated:

“... the complete reconstruction of the sacred area including the temples of Apollo and Bellona and the portico behind it, together with other monumental buildings around the Circus Flaminius, including ... the porticus Metelli”, (my translation).

Tonio Hölscher (referenced below, at p. 319) observed that, since the original temple:

“... was situated further to the south that its successor, ... it was clearly torn down by Caesar of the young Octavian [in the late 1st century BC] to provide space for the new theatre.”

Temple of Apollo Sosianus

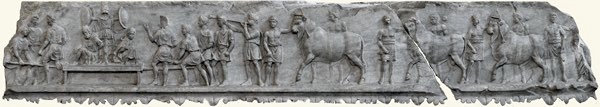

Frieze from the temple of Apollo in Circo (late 1st century BC), now in the Museo Centrale Montemartini, Rome

© 2014. Photo: Ilya Shurygin.

As noted above, excavations in 1932-33 and 1937-8 unearthed the podium of the original temple of Apollo on this site and extensive remains of the temple that replaced it. These included

✴the podium of the new temple, which was displaced to the north relative to the podium of the original temple;

✴the three Corinthian columns and their intricately carve architrave (illustrated at the top of the page) that were were rebuilt on the podium, although probably not in their original position; and

✴large fragments of a frieze, including those illustrated here.

In the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder referred to a statue:

“... [of] the ‘Dying Children of Niobe’ in templo Apollinis Sosiani, ... [although it is uncertain] whether it is the work of Scopas or of Praxiteles”, (‘Natural History’, 36: 4 [28]).

From this, it is likely that the man responsible for rebuilding the temple had been C. Sosius (see below). Tonio Hölscher (referenced below, at p. 319) argued that the frieze illustrated above depicted the triumphal procession from Octavian’s triple triumph of 29 BC (for his victories in Illyricum, at Actium, and over Cleopatra in Egypt). In other words, this temple must have been completed after 29 BC.

Pliny the Elder recorded that:

“There is a statue of Apollo Sosianus in cedar in a temple at Rome that was originally brought from Seleucia”, (‘Natural History’, 13: 11 [53]).

This statue might well have been in the temple of Apollo Sosianus

C. Sosius

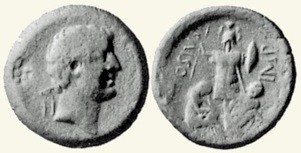

Coin (RPC 1: 1291) issued at Zakynthus in ca. 36 BC to commemorate Sosius’ conquest of Jerusalem

Obverse : head of Mark Antony

Reverse: trophy two mourning Jewish captives, with the inscription C. SOSIUS IMP

C. Sosius first emerges as a prominent figure in 36 BC, when as Governor of Syria, he led the Roman army that placed Herod on the throne of Jerusalem. The coin illustrated ave, which was one of four that he issued from Zakynthus (Zante) in the 30s BC commemorates his victory, and the fasti Triumphales recorded the triumph of 3rd September 34 BC celebrated by:

“C. Sosius C.f. T.n., proconsul, from Judaea”.

Sosius returned to Rome at the time that the relationship between Octavian and Mark Antony finally ruptured beyond repair. He remained attached to Mark Antony, who had arranged for him to serve as consul in 32 BC, alongside with Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus. According to Cassius Dio:

“Domitius did not openly attempt any revolutionary measures, since he had experienced many disasters. Sosius, however, had had no experience with misfortunes, and so on the very first day of the year, he said much in praise of [Mark] Antony and inveighed much against [Octavian]. Indeed, he would have introduced measures immediately against the latter, had not Nonius Balbus, a tribune, prevented it. [Octavian ... did not enter the Senate at this time nor even live in the city ... But afterwards, he returned and convened the Senate, surrounding himself with a guard of soldiers and friends who carried concealed daggers; and sitting with the consuls upon his chair of state, he spoke from there at length and with moderation in defence of himself, and brought many accusations against Sosius and [Mark] Antony. And, when neither of the consuls themselves nor anyone else ventured to utter a word, he bade the senators come together again on a specified day, giving them to understand that he would prove by certain documents that Antony was in the wrong. The consuls, accordingly ... left the city secretly before the day appointed and later made their way to [Mark] Antony ...”, (‘Roman History’, 50: 2: 3-6).

Thus it was that Sosius played a prominent part in the Battle of Actium in 31 BC.

Cassius Dio noted that, after his victory in this battle:

“Octavian imposed fines upon many the senators and knights and the other leaders who had aided [Mark] Antony in any way and killed many others, although some he actually spared. Sosius was a conspicuous example of this last group: although he had often fought against [Octavian], and although was now hiding in exile and was not found until later, he was, nevertheless, saved”, (‘Roman History’, 51: 2: 4)

According to Velleius Paterculus”:

“Great clemency was shown in the victory: no-one was put to death and only the few who could not bring themselves even to become suppliants were banished. ... in the case of Sosius, it was the pledged word of L. Arruntius, [one of Octavian’s commanders at Actium and] a man famous for his old-time dignity, that saved him; later, [Octavian] preserved him unharmed, but only after long resisting his general inclination to clemency”, (‘Roman History’, 2: 86: 2).

Sosius was subsequently rehabilitated, to the extent that he was one of the XViri sacris faciundis at the time of the Secular Games (search on Sosius) of 17 BC.

Before assessing his part in the building of the temple that bore his name, it is convenient to discuss the significance of this area to Octavian/Augustus .

Octavian/Augustus and the South End of Circus Flaminius

Theatre of Marcellus

As noted above, the construction of the new temple had been necessitated by the construction of the Theatre of Marcellus. According to Cassius Dio, shortly before his assassination in 44 BC, Julius Caesar:

“... [who was] anxious to build a theatre, as Pompey had done, ,,, laid the foundations, but did not finish it; it was Augustus who later completed it and named it for his nephew, M. Marcellus. But Caesar was blamed for tearing down the dwellings and temples on the site, and also because he burned the statues, which were almost all of wood, and because, on finding large hoards of money, he appropriated them all”, (‘Roman History’, 43: 49: 2-3).

We hear no more about the project until 17 BC, when the ‘theatre in the Circus Flaminius’ was used on June 3rd and June 5th of the Secular Games (search on Flaminius). However, the theatre was not dedicated for another six years: Pliny the Elder recorded that, on 7th May in the consulship of M. Tubero and Paullus Fabius (11 BC):

“... at the dedication of the Theatre of Marcellus, ... Augustus became the first person at Rome to exhibit a tamed tiger in a cage ...”, (‘Natural History’, 8: 25).

As noted above, Augustus himself recorded that:

“On ground purchased for the most part from private owners, I built the theatre near the temple of Apollo which was to bear the name of my son-in‑law, M. Marcellus, [who had died in 23 BC]”, (‘Res Gestae’, 21).

Temple of Bellona

As discussed in my page on this temple, Appius Claudius Caecus had built it next to the temple of Apollo in Circo at the end of the 3rd century BC, and it subsequently remained closely associated with his branch of this ancient family. Appius Claudius Pulcher, the head of the family in the 30s BC, served as consul in 38 BC, the year in which Octavian married the Claudian Livia: he was therefore among the first members of the Roman élite to support Octavian against Mark Antony. He fought in Octavian’s war in Sicily with Sextus Pompeius in 38-6 BC and then served as proconsul in Spain in 34-2 BC, where he secured a triumph (as recorded in the fasti triumphales Barberini). This was his last-known military post, and he disappears from the surviving sources in 31 BC.

According to Ömür Harmansah (in Lothar Haselberger et al., referenced below, at p. 67), archeological evidence reveals that the temple of Bellona was a:

“... peripteral, hexastyle temple [that] had a deep pronaos and was raised on a high platform. The podium had a concrete core with a mixed aggregate of tufa that dates to the Augustan period; its encasing opus quadratum masonry has been completely robbed, and very little survives of the marble architectural decoration of the superstructure.”

This project was linked to the rebuilding of the temple of Apollo in Circo: Ömür Harmansah (as above) recorded that:

“An L-shaped peperino portico enveloped the NW edge of the precinct, both defining the compound of the temples of Apollo [Sosianus] and Bellona and screening the rising slopes of the Capitoline hill. Based on the dating of the sporadic pieces of architectural decoration, it is suggested that the [temple of Bellona] was reconstructed in roughly the same years with the renovations of the [temple of Apollo Sosianus], and was probably [re-dedicated] by Appius Claudius Pulcher, consul of 38 BC, in the year 33 or 32 BC, after his triumph over Spain.”

Sacrifices on Augustus’ Birthday

Hjort Lange (referenced below, at pp. 132-3) noted that:

“Numerous fasti record the feriae on 23rd September for Augustus’ birthday, and the notice [added to the fasti Arvalium in 12 BC] ... goes on to mention sacrifices to Mars, Neptune and Apollo.”

He translated this entry (at p. 133) as follows:

“Public Holiday by decree of the Senate because, on this day, Imperator Caesar Augustus, Pontifex Maximus, was born. [Sacrifices] to Mars and Neptune in the Campus [Martius; and to] Apollo at the theatre of Marcellus.”

He continued:

“The temples named were all in or near the Circus Flaminius, the temple of Apollo having been recently rebuilt by C. Sosius. ... the selection of divinities clearly reflects the association with the Actium victory of these three gods, who also shared in the dedication of the Victory Monument at [the new city of] Nicopolis, [which Octavian built near the site of his victory]: Apollo, Mars and Neptune were together honoured as authors of the great victory both at the site and through these ceremonies at Rome.”

Finally, he recorded (at p. 133, note 340 that:

“The fasti Palatii Urbinatis also record the celebration on 23rd September at Apollo’s temple, but add other [nearby] temples: Felicitas in the Campus Martius; and Jupiter Stator and Juno Regina in the Circus Flaminius (that is, the temples in the porticus Octaviae).”

According to Howard Scullard (referenced below, at p. 188 and p.264) the temple near the Theatre of Marcellus was given as ‘Apollini, Latonae ad Theatrum Marcelli’. Birte Poulsen (referenced below, at p. 408 and note 34) deduced that Apollo’s mother Leo/ Latona was also venerated at this temple (as and that she was also later venerated at Octavian’s temple of Apollo on the Palatine).

Sosius and the Temple of Apollo Sosianus

[In construction - see this Alan Gurval, referenced below, at pp. 116-9 and this brilliant blog by Mark Crittenden]

Read more:

Salerno E., “Rituals of War. The Fetiales and Augustus’ Legitimisation of the Civil Conflict’, in

van Diemen D. et al. (editors), “Conflicts in Antiquity: Textual and Material Perspectives”, (2018) Amsterdam , at 143-60

Watkins T., “L. Munatius Plancus: Serving and Surviving in the Roman Revolution”, (2018) London

Davies P., “Architecture Politics in Republican Rome”, (2017) Cambridge

Poplacean D. M., “The Business of ButcheryBellona and War, Society and Religion from Republic to Empire”, (2017) thesis of McGill University, Montréal

Russell A., “The Politics of Public Space in Republican Rome”, (2016) Cambridge

De Nuccio M., “La Decorazione Architettonica del Tempio di Bellona”, Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, 112 (2011), 191-26

Mayer R., “Building Gloria”, in:

Millett P. et al. (editors), “Ratio et Res Ipsa: Classical Essays Presented by Former Pupils to James Diggle on his Retirementat’, (2011) Cambridge, pp. 207-18

Rich J., “The Fetiales and Roman International Relations”, in:

Richardson J. H. and Santangelo F. (editors), “Priests and State in the Roman World”, (2011 ) Stuttgart, at pp. 187-242

Bianchini M., “Le Sostruzioni del Tempio di Apollo Sosiano e del Portico Adiacente”, Mélanges de l’ École Française de Rome: Antiquité, 122-2, (2010) 525-48

Hölscher T., “Monuments of the Battle of Actium: Propaganda and Response”, in:

Edmondson J., (editor), “Augustus”, (2009) Edinburgh, at pp. 311-33

Lange C. H., “Res Publica Constituta: Actium, Apollo and the Accomplishment of the Triumviral Assignment”, (2009) Leiden and Boston

Poulsen B., “Sanctuaries of the Goddess of the Hunt”, in:

Fischer-Hansen T. and Poulsen B. (editors), “From Artemis to Diana: The Goddess of Man and Beast”, (2009) Copenhagen, at pp. 401-26

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume IV: Book X”, (2007) Oxford

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume IV: Book IX”, (2005) Oxford

Painter B., “Mussolini's Rome: Rebuilding the Eternal City”, (2005) New York

Aicher P., “Rome Alive: A Source Guide to the Ancient City, Vol. 1”, (2004) Mundelein ILL

Campbell C., “Uncompleted Theatres of Rome”, Theatre Journal, 55:1 (2003) 67-79

Haselberger L. et al. (editors), “Mapping Augustan Rome”, (2002) Portsmouth, RI

Flower H., “The Tradition of the Spolia Opima: M. Claudius Marcellus and Augustus”, Classical Antiquity, 19:1 (2000) 34-64

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume II: Books VII and VIII”, (1998) Oxford

Orlin E., “Temples, Religion and Politics in the Roman Republic”, (1997) Leiden, New York, Cologne

Viscogliosi A., “Il Tempio di Apollo in Circo e la Formazione del Linguaggio Architettonico Augusteo”, (1996) Rome

Gurval R. A., “Actium and Augustus.: The Politics and Emotions of Civil War”, (1995) Ann Arbor MI

La Rocca E., “Columna Bellica”, in:

Steinby E. M. (editor), ‘Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, Volume I’, (1993) Rome, at pp. 300-1

Syme R., “Augustan Aristocracy”, (1989) Oxford

Wiedemann T., “The Fetiales: A Reconsideration”, Classical Quarterly, 36: 2 (1986) 478-90

H. H. Scullard, “Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic”, (1981) London

Wiseman T. P., “Circus Flaminius”, Papers of the British School at Rome, 42 (1974) 3-26

Coarelli F., “Il Tempio di Bellona”, Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, 80 (1965-7) 37-72

Hanson J., “Roman Theater-Temples”, (1959) Princeton

Broughton T. R., “Magistrates of the Roman Republic: Volume I (509 - 100 BC)”, (1951) New York

Syme R., “The Roman Revolution”, (1939) Oxford

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)