Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temple of Diana in Aventino

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temple of Diana in Aventino

Foundation of the Temple

Our surviving sources unanimously record that Servius Tullius (traditionally the second king of Rome in 578-535 BC) founded a temple of Diana on the Aventine. As we shall see, this temple played a prominent part in the Romans’ understanding of their early history, although little further is known about it before its restoration at some time after 36 BC (see below). We do however know its dies natalis, since:

✴the pre-Julian fasti Antiates Maiores recorded a temple of Diana that had been dedicated the Ides (13th) of August, an anniversary that it shared with a number of other temples, including that of Vortumnus; and

✴the corresponding entries in some of the later fasti specified the location of these two temples:

•the fasti Allifani and the fasti Amiternini referred to Diana/ Vortumnus in Aventino;

•the fasti Arvalium similarly referred to Diana/ [Vortumnus] in Aventino; and

•the fasti Vallenses referred to Diana in Aventino and Vortumnus in [Vicus] Loreto Maiore, [a street on the Aventine].

Restoration by L. Cornificius

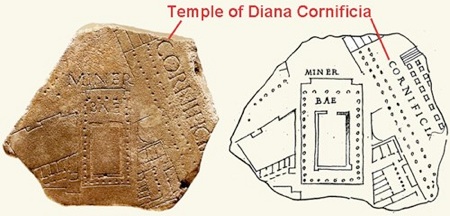

Rome: Forma Urbis Roma, plan of Temples of Diana and Minerva

From the website Athena Review Image Archive (my additions in red)

No remains of this temple have yet been identified, but we know from Suetonius that Octavian/ Augustus (in addition to his own extensive programme of public works at Rome):

“... often urged other prominent men to adorn the City with new monuments or to restore and embellish old ones. Many such works were [undertaken] by many men at that time ... [including] the temple of Diana by L. Cornificius ...”, (‘Life of Augustus’, 29).

Although it is unclear from Suetonius’ text whether Cornificius restored an existing temple or built a new one, surviving evidence from the imperial period suggests that he restored the temple of Diana on the Aventine:

✴an inscription (CIL VI 4305, 54-70 AD) that was found on the Via Appia outside Rome recorded a dedication made by a freedman of the Emperor Claudius who was the aedituus (temple guardian) of the temple of Diana Cornificia (or Cornificiana);

✴an inscription (CIL VI 29844, ca. 205 AD ) on the Severan plan known as the Forma Urbis Roma (see the illustration above) recorded the location of a two temples, one dedicated to Minerva and a scond and larger one dedicated to ‘... Cornificia’; and

✴templum Dianae et Minervae appeared in the list of Roman monument in Regio XIII Aventinus in the Chronography of 354 AD.

We might reasonably assume that Cornificius restored the temple of Diana in Aventino.

Furthermore, we might locate the context in which Cornificius restored this temple: as Olivier Hekster and John Rich (referenced below, at p. 154) observed, the land manoeuvres that preceded Octavian’s naval victory against Sextus Pompeius off Naulochus (Sicily) in 36 BC took place near a rural sanctuary of Artemis Phacelitis close to Mylae. They suggested (at pp. 154-5) that:

“The proximity of this sanctuary was evidently the basis for the association of Artemis/Diana with Octavian's victory, which is attested in various coin issues and may perhaps have led L. Cornificius, who was one of Octavian's legates in the Naulochus campaign, to choose the Aventine temple of Diana for rebuilding after his later triumph. An aureus (RIC I² Augustus 273) of the IMP CAESAR series issued at about the time of [Octavian’s victory over Mark Antony at Actium in 27 BC] has a bust of Diana on the obverse and, on the reverse, a temple enclosing a military trophy on a naval base; in the pediment of the temple stands a triskeles, the three-legged emblem of Sicily, clearly identifying the victory in question as Naulochus.”

Cornificius went on to become consul in 35 BC and proconsul in Africa in 34-2 BC: he triumphed ex Africa on 3rd December 32 BC and then disappears from our surviving sources.

In order to attempt to date his restoration of this temple, we should complete the list by Suetonius (above) of the monuments that were built or rebuilt in Rome at the behest of Octavian/ Augustus:

“Many such works were [undertaken] by many men at that time: for example:

✴the temple of Saturn, by L. Munatius Plancus*, [who triumphed ex Gallia in 43 BC];

✴the Atrium Libertas, by [C.] Asinius Pollio*, [who triumphed ex Parthia in 39 BC];

✴an amphitheatre [in the Campus Martius], by [T.] Statilius Taurus**, [who triumphed ex Africa in 34 BC and who completed and dedicated the amphitheatre in 30 BC];

✴the temple of Hercules and the Muses, by [L.] Marcius Philippus**, [who triumphed ex Africa in 33 BC];

✴the temple of Diana, by L. Cornificius**, [who triumphed ex Africa in 32 BC];

✴a theatre, by [L.] Cornelius Balbus**, [who triumphed ex Africa in 19 BC]; and

✴in particular, many magnificent structures, by M. Agrippa**, [who was offered but declined a triumph in 19 BC]”, (‘Life of Augustus’, 29).

As Frederick Shipley (referenced below. at p. 13) pointed out, all the men in Suetonius’ list had triumphed: I have:

✴re-ordered Suetonius’ list here to reflect the chronology of the respective triumphs, which were all awarded under the triumvirs or (after Actium) under Augustus; and

✴marked the partisans of Mark Antony with one asterisk and the partisans of Octavian/ Augustus with two.

We might usefully add C. Sosius to this list: he was associated with Mark Antony when he triumphed over Judea in 34 BC, and subsequently rebuilt the temple of Apollo Medicus, perhaps after his documented reconciliation with Augustus.

Diana's connection with the victory in Sicily is most emphatically celebrated [in Octavian’s coinage] on a series of aurei and denarii issued at Lugdunum in ca. 15-10 BC, in belated commemoration of the victories in Sicily and at Actium. The reverses of these issues show figures of:

Apollo, the lyre-player, ... [with the legend ACT underneath - see, for example, RIC I² Augustus 170]; and

Diana, the huntress, ... [with the legend SICIL underneath - see, for example, RIC I² Augustus 196].”

According to Varro, who was writing in ca. 45 BC:

“The name of the Aventine has several possible origins:

✴Naevius says that it is from the aves (birds), because the birds flew there from the Tiber;

✴others say that it was named for the Alban king, Aventinus, because he is buried there; while

✴still others say that it [was originally the ‘Adventine’ Hill, ab adventu hominum (from ‘the coming of men’), because all the Latins had rights in common at the temple of Diana that had been established there.

I am decidedly of the opinion, that it is from advectus (transport by water) since, in ancient times, the hill was cut off from everything else by swampy pools and streams. Therefore, people advehebantur (were conveyed) there by rafts”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 5: 43, translated by Roland Kent, referenced below, Vol. I, at pp. 39-41).

The grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus (as epitomised by Festus) recorded that, at his time of writing (probably early in the 1st century AD):

“The Ides of August is thought by the common people to be a festival day for slaves because, on that day, Servius Tullius, who was born a slave, dedicated aedem Dianae ... in Aventino (the temple of Diana on the Aventine)”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 460 Lindsay, translated by Carin Green, referenced below, at p. 200).

I discuss the tradition that ‘all the Latins had rights in common’ at this temple below. For the moment, we should note that Varro documented the existence of this temple on the Aventine in ca. 45 BC.

Denarius serratus issued in Rome by A. Postumius Albinus (RRC 372/1, 81 BC)

Obverse: Bust of Diana (with bow and quiver over her shoulder), with a bucranium (skull of a sacrificed bull) above

Reverse: A·POST·A·F·S·N·A͡LBIN: Priest preparing a bull for sacrifice at the altar of Diana on the Aventine (see below)

Denarius issued in Rome by A. Postumius Albinus (RRC 335/9, ca. 96 BC)

Obverse: Bust of Diana (with bow and quiver over her shoulder)

Reverse: A·A͡LBINVS·S·F: Three horsemen charging towards two standards and a fallen enemy soldier

Livy is our earliest surviving narrative source for the founding of the archaic shrine of Diana on the Aventine. In his account, Servius Tullius :

“... endeavoured to increase his dominion by means of diplomacy while, at the same time, adding splendour to the City. The temple of Diana at Ephesus, which was already famous at that time, had reputedly been built as a joint enterprise by the cities of Asia [i.e., by the Ionian League]. Servius lavishly praised this communal act of worship to the Latin leaders with whom he had assiduously cultivated ties of hospitality and friendship ... [and thus] convinced [them] to join with the Roman people in building a temple to Diana at Rome. This was an admission [on the part of the Latins] that caput rerum Romam esse (Rome was the leader of their affairs)”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 45: 1-3).

Miracle of the Sabine Heifer: a Portent of Rome’s Future Greatness

The sacrificial scene on the reverse of the denarius serratus (RRC 372/1) illustrated above refers to an anecdote that Livy reproduced in the next part of his account:

“It is said that a heifer of wondrous size and beauty was born in Sabine territory, on the property of a certain head of a family. ... This heifer was considered to be a prodigy, as indeed it was. Cecinere vates (inspired prophets foretold) that the state whose citizen should sacrifice the animal to Diana was destined to become fore imperium (the seat of empire). On the first suitable day for sacrifice, the Sabine led the heifer to the temple of Diana in Rome and set it before the altar. The priest [of Diana’s temple, who had heard of this prophecy, insisted that he should first purify himself in the Tiber, which he duly did.] Meanwhile the Roman [priest] sacrificed the heifer to Diana, an act that was wonderfully gratifying to both the king and the citizens”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 45: 4-7).

Alex Nice (referenced below, at p. 159) observed that this anecdote represents:

“... the first prophecy in Livy that explicitly foretells the destiny of the Roman state, and as such has special significance. Livy describes these events with language appropriate to prophecy and divination. ... The phraseology of cecinere vates … ibi fore imperium foreshadows the diction of the subsequent prophecy relating to the future greatness of Rome.”

He returned to this point (at p. 161), observing that:

“The significance of the Sabine [heifer] episode becomes clearer ten chapters later: [according to Livy], while Tarquinius Superbus was rebuilding the Capitol there were two indications of the future which confirmed the prophecy already made in connection with the Sabine [heifer].

✴The first occurs after the consultation of the birds, [which indicated that Terminus’ refusal to be moved from the site that was being cleared for the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus] portended the permanence of Rome.]

✴This predicator of the future was confirmed by the discovery of a human head during the construction of the temple foundations.”

The Livian passage in question related that:

“When this auspice of permanence had been received, there followed another prodigy foretelling the grandeur of their empire. A human head, its features intact, was found (it is said) by the men who were digging for the foundations of the temple. This appearance imperii caputque rerum fore portendebat (portended that here would be the seat of empire and the head of the world), and so cecinere vates (inspired prophets foretold), both those in the City and those summoned from Etruria”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 55: 5-6).

Diana Aventina and the Coins of the Postumii Albini

In his account of the miracle of the Sabine heifer (in a passage that seems to belong after line 7), Livy noted that:

“... for several years, [the] horns [of the Sabine heifer, which were] affixed in the vestibule of the temple of Diana [on the Aventine], had been a memorial of [the] miracle [of its prodigious size and beauty]”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 45: 6).

Beatrice Poletti (referenced below, at p. 40) suggested that the bucranium (bovine skull) above the bust of Diana on the obverse of RRC 372/1 (illustrated above):

“... explicitly recalls the detail of the heifer’s horns fixed in Diana’s temple, and may signify that the Postumii claimed among their ancestors the priest who tricked the Sabine and ensured the fulfilment of the prodigy to Rome’s advantage.”

It certainly put beyond doubt that the scene of the reverse took place at the altar of Diana Aventina, because we know from Plutarch that the bovine horns displayed there were extremely distinctive:

“Why in the other temples of Artemis, [Roman Diana], do they usually nail up stags’ antlers, but in the Aventine [temple] bovine horns ? Perhapsas a reminder of an ancient occurrence? For they say that, among the Sabines, a heifer was born to Antro Curatius, beautiful in appearance and surpassing all others in size. When a certain soothsayer told [Antro] that it was fated that the city of the one who should sacrifice that heifer to Artemis on the Aventine would become the mightiest and would rule over all Italy, the man went to Rome in order to sacrifice the heifer [there]. But, as a household slave had secretly revealed the prophecy to king Servius, who told the priest Cornelius, Cornelius [in turn] ordered Antro to bathe in the Tiber before the sacrifice ... Then, while [Antro] went away to bathe, Servius quickly sacrificed the heifer to the goddess and nailed up the horns in the shrine. Both Juba [II of Mauritania] and Varro recorded this account, except that Varro:

✴did not report the name of Antro, and he

✴said that the Sabine was deceived not by Cornelius the priest but by the guardian of the temple”, (‘Roman Questions ‘, 4, based on the translation by Beatrice Poletti, referenced below, at p. 50).

It does, therefore, seem certain that A. Postumius Albinus was intent upon associating his family with the miracle of the Sabine heifer, which (as we have seen) was understood as a portent of Roman hegemony.

Beatrice Poletti (referenced below, at pp. 39-40) also pointed out that A. Postumius Albinus, the moneyer of 81 BC:

“... has been identified as a grandson of Sp. Postumius Albinus (cos. 110 BC) and, possibly, a son of the A. Postumius Albinus who, in [ca. 96 BC], had issued a denarius, [RRC 335/9], that featured:

✴an almost identical bust of Diana [on its obverse]; and

✴a scene of battle with three equestrians charging a falling warrior [on its reverse].

This [earlier] emission was in celebration of Rome’s victory [over the Latins] at Lake Regillus in 499 or 496 BC, ... [when] the Romans fought under the command of the dictator A. Postumius Albus Regillensis (allegedly, the moneyer’s ancestor) ... The representation of Diana on this earlier coin ... can safely be interpreted as an allusion to the sacrifice of the prodigious heifer [at her altar on the Aventine in the reign of Servius Tullius], which portended Rome’s hegemony over the Latin cities and thus anticipated the victorious outcome of [this] battle.”

The evidence of RRC 335/9 and RRC 372/1, taken together, securely attests to the fact that the Diana’s cult site on the Aventine was closely associated in Roman hegemony over the Latins, at least by ca. 96 BC.

Diana Aventina and Diana Nemorensis

As Valerie Warrior (referenced below, at p. 64, note 135) pointed out:

“There was already a temple to Diana at Aricia in the Alban hills, which served as the federal cult centre of nine Latin communities to which Rome, being under Etruscan domination [at this time], did not belong. Servius Tullius’ building of a temple to Diana in Rome is evidently a bid to outdo the cult at Aricia.”

Dionysius had a slightly different opinion of the original function of this pan-Latin temple. He observed that the examples of:

“... the Ionians building the temple of Diana at Ephesus and the Dorians that of Apollo at Triopium [for regular festivals of their respective cities] ... inspired Servius Tullius with a desire of unite all the cities of Latium, so that they might avoid strife at home, wars among themselves and threats to their liberty from the neighbouring barbarians. He therefore called together the most important men of every [Latin] cities ... [and convinced them that] the Romans ought to have the leadership of all the Latins ... He then advised them to build a temple of refuge at Rome at their joint expense, [where they would hold annual festivals, ... and he secured their agreement to] the appointment of a general council [of the Latin cities]. Thereafter,with the money contributed by all the cities, he built the temple of Diana, which stands upon the Aventine, the largest of all the hills in Rome”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 25: 4 - 26: 4).

Importantly, Dionysius added that Servius:

“... also drew up laws relating to the mutual rights of the cities and prescribed the manner in which everything else that concerned the festival and the general assembly should be performed. In order that the passage of time should not obliterate these laws, he erected a bronze pillar upon which he engraved both the decrees of the council and the names of the cities that had taken part in it. This pillar still existed down to my time in the temple of Diana, with the inscription in the characters that were anciently used in Greece”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 26: 4-5).

Strabo

“In earlier times,... [the people of Massilia] were exceptionally fortunate, ... [particularly] in their friendship with the Romans, of which one may detect many signs; what is more, the xoanon (archaic wooden cult image) of the Artemis, [Roman Diana] on the Aventine Hill was constructed by the Romans on the same artistic design as that which the Massiliotes have. But at the time of Pompey's sedition against Caesar they joined the conquered party and thus threw away the greater part of their prosperity”, (‘Geography’, 4: 1: 5).

Read more:

Poletti B., “Livy and the Kingdom of Servius Tullius: Notes on the Foundation of the Aventine Cult of Diana (Liv. 1, 45)”, in”

Gillmeister A. (editor), “Rerum Gestarum Monumentis et Memoriae: Cultural Readings in Livy”, (2018) Warsaw

Rich J., “The Triumph in the Roman Republic: Frequency, Fluctuation and Policy”, in:

Lange C. J. and Vervaet F. (editors), “The Roman Republican Triumph: Beyond the Spectacle”, (2014 ) Rome, at pp. 197-258

Green C. M. C., “Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia”, (2006) Cambridg and New York

Hekster O. and Rich J., “Octavian and the Thunderbolt: The Temple of Apollo Palatinus and Roman Traditions of Temple Building”, Classical Quarterly, 56:1 (2006) 149-68

Warrior V. M., “Livy: History of Rome, Books 1–5 (Translated, with Introduction and Notes)”, (2006) Indianapolis IN

Nice A., “Divination and Roman Historiography”, (1999) thesis of Exeter University

Kent R. (translator), “Varro: On the Latin Language, Vol. I (Books 5-7) and Vol. II (Books 8-10 and Fragments”, (1938) Cambridge, MA

Shipley F. W, “Chronology of the Building Operations in Rome from the Death of Caesar to the Death of Augustus”, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 9 (1931) 7-60

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)