Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temple of Juno Regina on the Aventine

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temple of Juno Regina on the Aventine

Juno, Queen of the Gods

Nancy Thomson de Grummond and Erika Simon (referenced below, at p. 61) observed that, from an early date, the Greek goddess Hera, the wife of Zeus, was widely venerated:

✴by the Latins and Faliscans as Juno; and

✴by the Etruscans as Uni.

This goddess seems to have been worshipped at Rome in the Regal period: as Howard Scullard (referenced below, at p. 19) observed:

“The most famous of Rome's temples was that on the Capitol, [which was] begun by Tarquinius Priscus, completed by Tarquinius Superbus, and dedicated in the first year of the Republic to the Etruscan triad, Tinia, Uni and Menrva under the Roman form of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva.”

However, the earliest known Roman temple dedicated to Juno alone was built on the Aventine by the dictator M. Furius Camillus to house a cult statue of Uni that he captured in 396 BC, after the Roman subjugation of the Etruscan city-state of Veii.

Calling of Uni/Juno from Veii (396 BC)

Green = Etruscan city-states of Veii, Caere and Volsinii

Sources

Livy

According to Livy, on the eve of the Romans’ last and decisive engagement in their long war with Veii, after the dictator Camillus had:

“... taken the auspices and issued orders for the soldiers to arm for battle, he uttered this prayer:

“Juno Regina, who presently resides in Veii, I pray that you follow us in our victory into the city that is ours and will soon be yours, where a temple worthy of your greatness will receive you”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 21: 3).

Veii duly fell, and after the Romans had seized:

“... the wealth that belonged to men, ... they began to remove the gods’ gifts and the gods themselves, but did so more in the manner of worshipers than plunderers. Young men were chosen from the whole army and were assigned the task of bringing Juno Regina to Rome. ... [We] hear that she was easily moved from her place ... and was lightly and easily ... carried, safe and sound, to the Aventine, the eternal home to which [Camillus’] prayers had called her; and there, Camillus afterwards dedicated to her the temple that he himself had vowed”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 22: 3-7).

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus gave a shorter but essentially similar account account, with the addition of the claim that the young men repeated their question to Juno in order to be sure that they had heard her correctly:

“This same Camillus, when conducting his campaign against Veii, made a vow to Queen Juno of the Veientines that, if he should take the city, he would set up her statue in Rome and establish costly rites in her honour. Accordingly, upon the capture of the city, he sent the most distinguished of the knights to remove the statue from its pedestal. When they came into the temple and one of them ... asked whether the goddess wished to move to Rome, the statue answered in a loud voice that she did. This happened twice; for the young men, doubting whether it was the statue that had spoken, asked the same question again and heard the same reply”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 13: 3).

Plutarch

Plutarch, who cited Livy, nevertheless introduced an important variant of this legend, in which Camillus himself asked Juno to agree to move to Rome:

“After [Camillus] had utterly sacked the city, he determined to transfer the image of Juno to Rome in accordance with his vows. It is said that, when the workmen were assembled for the purpose, and as Camillus was sacrificing and praying that the goddess would accept of their zeal and [agree to join] the gods of Rome, the image spoke in low tones and said she was ready and willing. However, Livy says that Camillus did indeed lay his hand upon the goddess and pray and beseech her, but that it was certain of the bystanders who gave answer that she was ready and willing and eager to go along with him”, (‘Life of Camillus’, 6: 1-2).

Roman Isaenko (referenced below, at p. 24) argued that:

“... [since] Plutarch names Livy as his source, it can be assumed that ... [he] merely forgot about the young warriors, [who, according to Livy, had been charged with asking the goddess to acquiesce and whom Livy ] never again mentioned... [He therefore] naturally ascribed their actions to Camillus, the man who plays the most prominent part in [Livy’s Book 5]. Another, less likely. possibility is that Plutarch knew of a different version of the legend that he misattributed to Livy.”

Evocatio Deorum ?

Festus (probably following the Augustan scholar M. Verrius Flaccus) recorded that the Romans regarded as peregina (foreign) those cults that were observed at Rome:

“... for gods:

✴who were ‘called forth’ [by the Romans] ... in the course of besieging their cities and forcibly brought to Rome; or

✴who, on account of some religious scruple, the Romans had sought in peace, such as:

•the Magna Mater from Phrygia;

•Ceres from Greece; [and]

•Aesculapius from Epidauros;

[all of whom] are worshipped according to the custom of those from whom they were received”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 268 L, based on the translation by Eric Orlin, referenced below, 2015, search on Festus).

In this passage, Festus/ Verrius Flaccus used the verb evocare (to summon or call forth) in relation to the Romans’ appropriation of foreign gods during war. Pliny the Elder elaborated on the ritual nature of this process, at least as he understood it in the 1st century AD:

“Verrius Flaccus cites reliable authors to show that, at the start of a siege, it was the custom for the Roman priests to summon forth the tutelary divinity of that particular town, and to promise him the same rites, or even a more extended worship, at Rome; and this ritual still forms part of our pontifical law even at the present day”, (‘Natural History’, 28: 4).

Macrobius, who was writing in the early 5th century AD, also described such a ritual:

“[It] is commonly understood that all cities are protected by some god, and that it was a secret custom of the Romans ... that, when they were laying siege to an enemy city and were confident that it could be taken, they used a specific spell evocarent tutelares deos (to call out the gods that protected it), either because they believed the city could not otherwise be taken or (even if it could be taken) they thought it against divine law to hold gods captive”, (‘Saturnalia’, 3: 9, translated by Robert Kaster, referenced below).

Modern scholars refer to this putative ritual as evocatio deorum and often cite four occasions when this putative ritual was used:

✴in 396 BC, for the calling of Juno from Veii;

✴in ca. 264 BC, for the calling of Vortumnus from Volsinii;

✴in ca. 241 BC, for the calling of Juno Curitis from Falerii; and

✴in 146 BC, for the calling of Juno Caelestis (Tanit) from Carthage.

For example, Giorgio Ferri (referenced below) devoted a chapter to each of these putative examples. It is certainly true that each of them coincided with the end of the city in question as a political force. However, Eric Orlin (referenced below, 2015, search on ‘looms’) argued that:

“... the evocatio looms much larger in the Roman imagination ... than it seems to have done in practice. That is, the Romans believed they had a tradition of calling out the divinities of besieged towns, but they seem to have done it in practice only rarely; the Veii example is one of the few reported instances accepted as historical by most scholars, and even [this claim] has its detractors.”

Roman Isaenko (referenced below) is one of these detractors: he pointed out (in his abstract at p. 23) that, even in the case of Veii:

“.. none of the... [surviving] accounts of the statue’s transfer ... [to Rome] present it as a part of a [recognised] ritual.”

He concluded that:

“... the legend of the transfer of Juno Regina is not meant to depict a particular ritual, and has emerged merely to provide an explanation of the fact that the ancient Etruscan image [from Veii] has found its place in Rome.”

Calling of Uni/Juno from Veii: Conclusions

Our surviving sources indicate that, at least by the Augustan period, the Romans believed that Camillus had won the acquiescence of Uni, the patron goddess of Veii, to her transfer to Rome. In Roman eyes (and perhaps in reality), the physical transfer of this cult image of Uni to the Aventine marked Rome’s complete subjugation of Veii. This was to be the first step in the long process of conquering Etruria, which finally ended with the fall of Volsinii in 264 BC (and of the calling of of Voltumnus from Volsinii to Rome).

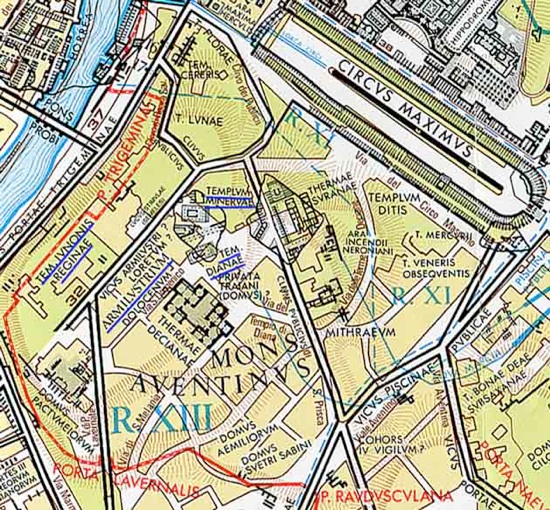

Temple of Juno Regina on the Aventine

Adapted from Francesco Marcattili ( referenced below, para. 3, fig. 1)

The Temple of Juno Regina on the Aventine was reached from the clivus Publicus,

up the northern slope of the hill, and was probably located near the later church of Santa Sabina

Foundation of the Temple

According to Livy, in 396 BC;

✴on the eve of the Romans’ final defeat of Veii, after the dictator Camillus had:

“... uttered this prayer:

‘Juno Regina, who presently resides in Veii, I pray that you follow us in our victory into the city that is ours and will soon be yours, where a temple worthy of your greatness will receive you’”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 21: 3);

✴after the Romans’ victory:

“[We] hear that Juno Regina] was easily moved from her place [at Veii] ... and was lightly and easily ... carried, safe and sound, to the Aventine, the eternal home to which [Camillus’] prayers had called her; and there, Camillus afterwards dedicated to her the temple that he himself had vowed”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 22: 3-7); and

✴when Camillus returned to Rome in triumph:

“... he let the contract for building the temple of Juno Regina on the Aventine and dedicated another to Mater Matuta. After having thus discharged his duties to gods and men, he resigned his dictatorship”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 23: 5-7).

Then, 392 BC, the consuls:

“... L. Valerius Potitus and M. Manlius, later surnamed Capitolinus celebrated the ‘Great Games’ that [Camillus] had vowed when dictator in [396 BC]. This year saw also the dedication of a temple to Juno Regina, which had been vowed by the same dictator in the same war. The tradition says that this dedication excited great interest amongst the matrons, who were present in large numbers”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 31: 2-3).

The fasti Fratres Arvales (CIL VI 2295, ca. 30 BC) record the dies natalis of the temple Iunoni Reginae in Aventino as the 1st September.

Adam Ziolkowski (referenced below, at p. 237) pointed out:

✴the temple of Juno Regina on the Aventine was the first Republican temple to be vowed, contracted for and dedicated by the same person; and

✴Camillus held no office in 392 BC, and so was presumably appointed as duovir aedis dedicandae for the purpose.

Location of the Temple

Livy and the fasti Fratres Arvales placed Camillus’ temple on the Aventine. Its location is suggested by Livy’s description of the events of 207 BC, when:

“... the temple of Juno Regina, on the Aventine, was struck by lightning. ... Immediately, a day was given out by the decemviri for another sacrifice to the same goddess, which was performed in the following order:

✴two white heifers were led from the temple of Apollo into the city through the porta Carmentalis;

✴after these came two cypress images of Juno Regina;

✴followed by 27 virgins, arrayed in white vestments and singing in honour of Juno Regina ... ; and, finally

✴the decemviri, crowned with laurel, and in purple-bordered robes.

From the porta Carmentalis, they:

✴proceeded by the vicus Jugarius into the forum ... :

✴continued up the vicus Tuscus and into the Velabrum;

✴passed through the forum Boarium;

✴continued up the clivus Publicius; and

✴arrived at the temple of Juno Regina, where the decemviri [performed the sacrifice] and the cypress images [of the goddess] were carried into the temple”, (‘History of Rome’, .27: 37: 11-5).

A pair of inscriptions (ca. 150 AD) that were found near the church of Santa Sabina (which were documented before they were lost) might well indicate the approximate location of her temple:

✴CIL VI 365: Iunoni/ Reginae/ Paezon, Aquiliaes/ Bassillaes actor/ cum Paezusa/ filia sua, d(ono) d(edit); and

✴CIL VI 366: Iovi Optimo/ Maximo Dolichen(o)/ Paezon, Aquiliaes/ Bassillaes actor cum Paezusa/ filia sua/ d(ono) d(edit).

These inscriptions recorded dedications made by Paezon and his daughter, Paezusa (both slaves of Aquilia Bassillia) to Juno Regina and to Jupiter Dolichenus: the latter was the Jupiter of the city of Doliche in north-west Syria, whose consort was Juno Regina Dolichena and whose cult spread throughout the Roman world in the 2nd century BC. Significantly, for our purposes, Jupiter Dolichenus had a temple on the Aventine, on the site of the Dominican convent at Santa Sabina - see, for example, Mary Beard et al, referenced below, at p.275 and Map 2, p. xviii-xix, entry 12).

Eric Orlin (referenced below, 2002, at p. 5) pointed out that the Aventine:

“... has long been recognised as a favourite spot [for the construction of temples devoted to newly-introduced foreign cults at Rome]; in chronological order, we can list temples [there] to:

✴Diana (supposedly erected by Servius Tullius, which we may take as an indication of a pre-republican foundation);

✴Mercury (dedicated in 495 BC);

✴Ceres, Liber and Libera (493 BC);

✴Juno Regina (392 BC);

✴Summanus (ca. 278 BC);

✴Vortumnus (ca. 264 BC); ... [and]

✴Minerva (whose temple [was founded at an unknown date before] the end of the third century BC).”

Interestingly, Vortumnus was probably ‘called’ from another Etruscan city-state, Volsinii: while the calling of Uni/ Juno from Veii marked the start of Rome’s subjugation of the Etruscans, the calling of Voltumna/ Vortumnus from Volsinii marked its completion.

Read more:

Isaenko R.,”Evocatio and the Transfer of Juno Regina from Veii”, Philologia Classica. 12: 1 (2017) 21-8

Orlin E., “Sacra Peregrina; ‘Foreignness’ in Roman Rites”, (2015) presented at the SBL annual meeting and published on-line

Marcattili F., “Per un’ Archeologia dell’ Aventino: i Culti della Media Repubblica”, Mélanges de l'École Française de Rome : Antiquité , 124:1 (2012) online

Kaster R. A.(translator), “Macrobius: Saturnalia, Volume I: Books 1-2”, (2011) Cambridge MA

Ferri G., “Tutela Urbis: Il Significato e la Concezione della Divinità Tutelare Cittadina nella Religione Romana”, (2009) Stuttgart

Thomson de Grummond N.and Simon E., “Religion of the Etruscans”, (2006) Austin (Texas)

Orlin E., “Foreign Cults in Republican Rome: Rethinking the Pomerial Rule”, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 47 (2002) 1-18

Beard M., North J. and Price S., “Religions of Rome: Vol. I: A History”, (1998) Cambridge

Scullard H. H., “Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic”, (1981) London

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)