Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temple of Saturn

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temple of Saturn

Eight columns of the temple of Saturn (from the restoration of the late 4th century AD),

which stands to the left of the clivus Capitolinus (with three columns of the temple of Vespasian and Titus to the right)

Introduction

According to Macrobius:

“... Varro, in Book 6 of his ‘Sacred Temples’ [probably the now-lost ‘Antiquitates Rerum Humanarum et Divinarum’ - see Fr. 158 in this link] writes that:

✴Tarquinius [Superbus, traditionally the 7th and last king of Rome, reigning in 534-509 BC] contracted for the construction of the temple of Saturn ad forum’; and

✴the dictator T. Larcius [see below] dedicated it at the time of the Saturnalia”, (‘Saturnalia’, 1: 8: 1, translated by Robert Kaster, referenced below, Vol. I, at p. 85).

Livy, who did not mention the vowing or the construction of the temple recorded that, in the consulship of A. Sempronius and M. Minucius [traditionally 497 BC]:

“... a temple to Saturn was dedicated, and the Saturnalia (see below) was established as a festal day”, (‘History of Rome’, 2: 21: 2).

I discuss the conflicting sources for the date of the dedication of the temple below: for the moment, we might simply note that this was probably the first temple dedication for which Livy had an ‘official’ source (although he had already recorded that the consul M. Horatius had dedicated the temple of Jupiter on the Capitol in the first year after the expulsion of the kings). As we shall see:

✴all our surviving literary sources agree that the temple did indeed date back to the start of the Republic; and

✴surviving archeological and epigraphic evidence indicates that it was rebuilt on at least two occasions:

•in the late Republic; and then

•in the late 4th century AD.

According to the pre-Julian fasti Antiates maiores, its dies natalis coincided with the festival of the Saturnalia on 17th December.

Location of the Temple

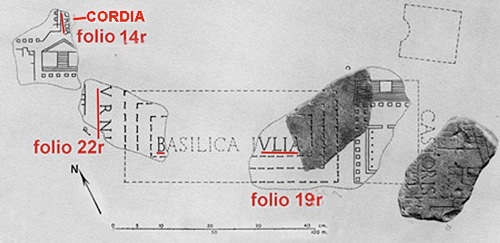

Possible reference to ‘aedis Saturni’ on the Forma Urbis Roma (see below)

Detail of Plate 1 of G. Carretoni et al. (referenced below), from the Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project

(My additions in red.)

There is no doubt about the location of this temple: as Amanda Claridge (referenced below, at p. 83) pointed out:

“The facade of eight Ionic columns on a tall footing of travertine blocks [that stands in the southwestern part of the Forum, opposite the remains of the temple of Vespasian and Titus in the clivus Capitolinus - see the photograph above] belongs to the temple of Saturn.”

This location is supported by a number of literary references to it (discussed below) and by one and possibly two Renaissance drawings of now-lost fragments of the Severan Forma Urbis Rome (now published on-line by Stanford University) that are shown as folios 14r and 22r on the reconstruction above:

✴Cod. Vat. Lat. 3439, folio 14r, which has an inscription that usually completed as (Aedis) [CON]CORDIA, although Lawrence Richardson (referenced below, at p. 58) suggested that it should probably be completed it as (Aedis) [VENUS VERTIC]ORDIA; and

✴Cod. Vat. Lat. 3439, folio 22r, which has two inscriptions that are usually completed as:

•B[ASILICA I]VLIA (with Cod. Vat. Lat., folio 19r); and

•(Aedis) [SAT]URNI.

In relation to the second of these fragments, note that Augustus recorded in his biography that:

“I completed the Basilica [Julia], which was between the temple of Castor and the temple of Saturn”, (‘Res Gestae,’ 20: 3).

Cult of Saturn

Examples of Republican ‘prow bonzes’ (As on the left, Semis on the right) struck in Rome (ca. 220 BC)

Both reverses: prow of a ship

Obverses: As (RRC 35/1) bifrons (two-faced) head of Janus; Semis (RRC 35/2) head of Saturn

According to Varro:

Macrobius gave three accounts of the origin of the Saturnalia, the first of which associated Saturn with Janus in a traditional account of the earliest history of Italy:

“The region now called Italy was ruled by Janus, who (as Hyginus reports, following Protarchus of Tralles) held this land together with Cameses, another native, in a power-sharing arrangement whereby the region was called Camesene and the settlement Janiculum. This arrangement was later reduced to the sole rule of Janus, who is held to have had two faces, so that he could see what was in front of him and what was behind ... When Saturn arrived[in Italy] by ship, Janus received him hospitably. [Saturn] and taught [Janus] about agriculture ... [and Janus] rewarded Saturn by making him a partner in his rule. When Janus became the first to coin money, ... he had the likeness of his own head stamped on one side of the coin and a ship stamped on the other, ... because Saturn had arrived by ship. (We know that bronze was stamped that way because, when boys [today] shout ‘heads’ or ‘ships’ when they toss coins in a game of chance, [a practice dating back to] ancient times). We know that Janus and Saturn ruled together in harmony and collaborated in founding neighbouring settlements from [Virgil], who writes [at ‘Aeneid’, 8: 358]:

‘This [settlement] was named Janiculum, that one was named Saturnia.’

It is also also obvious from the fact that later generations dedicated two neighbouring months to them: December is sacred to Saturn and January [is named for Janus]. When Saturn suddenly disappeared in the middle of their reign, Janus devised ways to increase his honours:

✴he named his entire kingdom ‘Saturnia’ ;

✴he established an altar, as though for a god, and sacred rites that he called the ‘Saturnalia’; (by so many centuries do these rites antedate the city of Rome!); and

✴he commanded that Saturn be revered with the majesty of religion as the author of a better way of life, a status that Janus indicated by adding a faix (sickle), the symbol of the harvest, to Saturn’ [cult] statue..

The people attribute to Saturn the grafting of shoots, the cultivation of fruit trees, and the method of all kinds of agricultural production. ... The Romans also call him Sterculius, because he first fertilised fields with stercus (manure). The time of his reign is said to have been the happiest, both because;

✴it was a time of material abundance; and

✴the distinction between slavery and freedom did not yet exist, as is made plain by the fact that slaves are allowed complete license during the Saturnalia”, (‘Saturnalia’, 1: 7: 19-26, based on the translations of by Robert Kaster, referenced below, Vol. I, at pp. 73-7and by Barbara Levick and Timothy Cornell, in Cornell T. C. (editor), referenced below, Vol. II, at p. 919).

Although Macrobius was writing in the 5th century AD, the sources that he cited at the start of his account were much earlier:

✴Julius Hyginuswas a freedman of Augustus; and

✴his source, Protarchus of Tralles

The earliest surviving material evidence for the Roman cult of Saturn is found in the coinage of the Republic: in the catalogue of these coins from 225 BC, when Janus and Saturn each made his first appearance on a coin minted at Rome:

✴Janus appeared on 78% (89/ 114) bronze asses; and

✴Saturn appeared on 81 % (105 /129) of bronze semises;

and almost all of these coins had the prow of a ship on the reverse.

According to Livy, when the consul

For the Saturnalia and other expiations of 217 BC, see Livy 22.1.8-20, Plutarch Fab . 2, Macrobius Sat . 1.6.13-14, Orosius 4.15.1, Val. Max. 1.6.5

After Flaminius’ defeat, the Senate worked as a body in the expiatory rituals of 217 BC, as they conducted the Saturnalia in December

Vowing and Dedication of the Archaic Temple

According to Macrobius:

“... Varro, in Book 6 of his ‘Sacred Temples’ [probably the now-lost ‘Antiquitates Rerum Humanarum et Divinarum’ - see Fr. 158 in this link] writes that:

✴Tarquinius [Superbus, traditionally the 7th and last king of Rome, reigning in 534-509 BC] contracted for the construction of the temple of Saturn ad forum’; and

✴the dictator T. Larcius [see below] dedicated it at the time of the Saturnalia (see below)”, (‘Saturnalia’, 1: 8: 1, translated by Robert Kaster, referenced below, Vol. I, at p. 85).

Livy, who did not mention the vowing or the construction of the temple recorded that, in the consulship of A. Sempronius and M. Minucius [traditionally 497 BC]:

“... a temple to Saturn was dedicated, and the Saturnalia (see below) was established as a festal day”, (‘History of Rome’, 2: 21: 2).

This was probably the first temple dedication for which Livy had an ‘official’ source (although he had already recorded that the consul M. Horatius had dedicated the temple of Jupiter on the Capitol in the first year after the expulsion of the kings).

Dionysius of Halicarnassus is our earliest surviving source to record the vowing of this temple: in his account, when Tullus Hostilius [traditionally the 3rd king of Rome, reigning in 672–640 BC] was under pressure in his battle with the Sabines:

“... he made a vow to the gods that, if he conquered the Sabines on that day, he would institute public festivals in honour of Saturn and [his putative consort, the goddess] Ops ...”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 32: 4).

Dionysius also recorded that:

“They say that ... the temple of Saturn, [which stands] on the ascent that leads from the Forum to the Capitol, was dedicated during [the consulship of A. Sempronius and M. Minucius] and annual festivals and sacrifices were appointed to be celebrated in honour of the god at the public expense. ... Some historians state that the credit for beginning this temple was given to T. Larcius, the consul of the previous year”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 6: 1: 4).

If we combine these two accounts, the Dionysius believed that the temple had been:

✴vowed by Tullus Hostilius;

✴begun by T. Larcius as consul for the second time in 498 BC; and

✴dedicated in the consulship of A. Sempronius and M. Minucius in 497 BC

In summary, Livy and Dionysius agreed that T. Larcius was consul:

✴for the first time in 501 BC; and

✴for the second time in 498 BC.

However, as Robert Broughton (referenced below, at p. 10, note 3) observed, they disagreed about the date of his dictatorship:

✴Livy followed the ‘most ancient authors’ and dated it to his first consulship (501 BC); while

✴Dionysius dated it to his second consulship (498 BC).

They both agreed that the temple was dedicated in the consulship of Sempronius and Minucius (497 BC), while Varro believed that Larcius had dedicated it as dictator (presumably in 501 or 498 BC). Dionysius knew of another tradition in which

“... the dedication fell to Postumus Cominius, [Larcius’ consular colleague in 501 BC] pursuant to a decree of the Senate”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 6: 1: 4).

While there is (unsurprisingly) significant variation in the detail of these three accounts, they agree that the temple was dedicated in the period 501-497 BC. John North Hopkins (referenced below, at pp. 143-4) pointed out that, although the archeological evidence from the temple foundations does not allow the precise dating of its original construction to be determined, there is no reason to doubt that it did indeed date back to the early 5th century BC.

Macrobius also noted that Aulus Gellius (ca. 125 BC) had recorded that:

“... the Senate decreed that the temple of Saturn be built, with the military tribune L. Furius in charge”, (‘Saturnalia’, 1: 8: 1, translated by Robert Kaster, referenced below, Vol. I, at pp. 85-7).

John Briscoe (in Cornell T. C. (editor), referenced below, Vol. III, at p. 239) argued that this must refer to a military tribune with consular powers, and:

“... it is [therefore] likely that the decision of the Senate in fact concerned the rebuilding of the temple after the Gallic sack, [in which case], the man named would ... be probably L. Furius Medullinus, who [traditionally held this post] in 381 and 370 BC and [was] censor in 363 BC.”

Ara Saturni (Altar of Saturn)

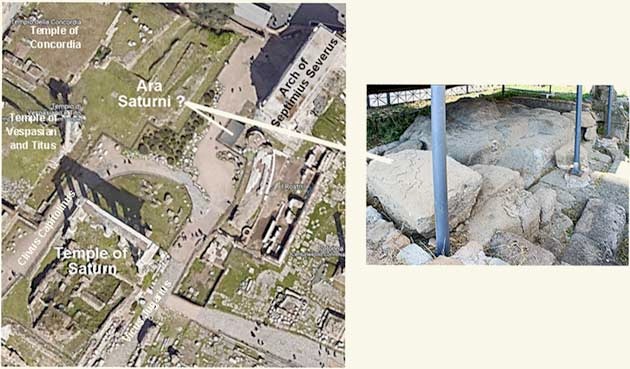

Possible location of the Ara Saturni

Left: satellite view of the protective roof over the putative remains of an archaic altar (Google Maps)

Right: remains under this roof, from an image in Jeff Bondono’s website on the Roman Forum (search Altar of Saturn)

Varro recorded that, before the time of Romulus, the Capitoline had been known as:

“... the mons Saturnius ... and, from this, Latium was known as terra Saturnia, as Ennius calls it. It is recorded that this hill was once the site of the ancient oppidum (town) of Saturnia. Even now, there are three [etymological] vestiges of the town:

✴[the name of the presumably surviving] Saturni fanum in faucibus; and

✴Porta Saturnia, which, according to Junius [Gracchanus, 2nd century BC], was the name of the gate that is now known as Porta Pandana; and

✴muri Saturnii, the name given to the back walls of the houses post aedem Saturni (behind the temple of Saturn) in laws relating to the buildings of private persons refer”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 5: 42, adapted from the translation by Roland Kent, referenced below, at p. 39).

Varro’s ‘Saturni fanum in faucibus’ was presumably distinct the aedes Saturni (the temple in front of the muri Saturnii). It might have contained the altar to which he alluded in a slightly later passage (although without specifying its location):

“... the ‘Annals’ record that, [after Romulus and the Sabine Titus Tatius had agreed to share power in Rome], Tatius vowed arae (altars) to ... [a number of Sabine deities, including] Vediovi Saturnoque (to Vediovis and Saturn) ...”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 5: 74, translated by Roland Kent, at p. 71).

However, Dionysius knew of a tradition that gave the altar a much earlier origin:

“They say that, before the foundation of the temple of Saturn, Hercules built an altar there, upon which, the [priests] to whom he had given the holy rites offered the first-fruits as burnt-offerings according to Greek custom”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 6: 1: 4).

Macrobius (who was writing in the 5th century AD) similarly recorded that:

“[Saturn] also has an altar before the Senaculum, [later the temple of Concordia in the Forum], where sacrifice is offered in the Greek manner ([i.e.,], with uncovered head), because it is thought that [sacrifice] was offered in that way from the beginning, first by the Pelasgi and later by Hercules”, (‘Saturnalia’, 1: 8: 2, translated by Robert Kaster, referenced below, Vol. I, at p. 87).

The grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus (as epitomised by Festus):

“Saturnia: Italia, et mons, qui nunc est Capitolinus, Saturnius appellabatur, quod in tutela Saturni esse existimantur. Saturni<i> quoque dicebantur, qui castrum in imo cliuo Capitolino incolebant, ubi ara dicata ei deo ante bellum Troianum uidetur, quia apud eam supplicant apertis capitibus. Nam Italici auctore Aenea uelant capita”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 430-2 Lindsay)

“Saturnia: this was the name of] Italy and of the hill that is now called the Capitoline, because it was supposed that [both Italy and the Roman hill] were under the guardianship of Saturn. Those who lived in castrum in imo cliuo Capitolino (the castrum at the bottom of the Clivus Capitolinus) were called Saturnians. An altar there was dedicated to [Saturn]: it seems that it pre-dated the Trojan War, since people pray there with their heads uncovered [while, after this war], the Italians covered their heads, following Aeneas' example ...”, (my translation).

On this basis, Varro’s ‘Saturni fanum in faucibus’ stood at the entrance to the Clivus Capitolinus from the Forum (see this translation of fauces in the context of places by Charlton Lewis and Charles Short). This was conceived as a castrum in this location that guarded the most convenient means of ascent to the Saturnian/ Capitoline hill.

Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, at p. 206) identified this altar as the putative archaic altar illustrated above, which the excavators had identified as the Volcanal and this hypothesis is usually accepted (see, for example, the commentaries of:

✴Carlos Norena, in the directory of Digital Augustan Rome; and

✴Jeff Bondono, in his website on the Roman Forum (search Altar of Saturn).

However, note that:

✴the site in the Forum is still labelled as the Volcanal; and

✴Lawrence Richardson (referenced below, at p. 53 and note 1) rejected Coarelli’s hypothesis and argued (at p. 52) that, based on Macrobius’ reference to the Senaculum, the altar:

“... must have stood between the temple of Concordia and the arch of Septimius Severus: its remains are [possibly] buried under the [present] Via del Foro Romano ...”

Aerarium Saturni

Denarius (RRC 441/1), issued by the quaestor urbanus Cn. Nerius

Obverse: N͡ERI·Q·V͡RB: Head of Saturn, with a harpa (sickle) over his left shoulder

Reverse: L·LEN͡T C·M͡ARC CO S: Legionary aquila (eagle), flanked by two other legionary standards

According to Verrius Flaccus (according to Paul the Deacon, in his epitome of Festus’ earlier epitome of Verrius’ lexicon):

“The aerarii tribuni (tribunes of the treasury) get their name from ‘tribuere aes’ (to distribute money). The Roman people, of course, kept the aerarium (treasury) in the temple of Saturn”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 2 Lindsay, translated by Ryland Patterson, referenced below, at p. 22).

Plutarch imagined that the institution was as old as the Republic, and that P. Valerius Publicola, one of the first men to be elected as consul:

“... received praise for his law concerning the public treasury. When it was necessary for the citizens to provide means for carrying on the war, he was unwilling ... to have public money stored in any private house. He therefore arranged for the temple of Saturn to be used as a treasury (as it is to this day) and gave the people the privilege of appointing two young men as quaestors or treasurers”, (‘Life of Publicola’, 12: 2.

There seem to have been a number of traditions surrounding the reason for the choice of the temple of Saturn for this purpose: for example, according to Macrobius:

“... the Romans wanted the temple of Saturn to be the treasury, because:

✴it is said that, when [Saturn] resided in Italy, no theft was committed in his territory; or else

✴[since] no-one held private property during his reign, ... the money that belonged in common to the people was placed in his temple ... ”, (‘Saturnalia’, 1: 8: 2, translated by Robert Kaster, referenced below, Vol. I, at p. 87).

This explains why the urban quaestor Cn. Nerius chose the head of Saturn for the denarius (RRC 441/1, illustrated above) that he issued in 49 BC and depicted on the reverse the legionary standards that were kept in the aerarium there.

The circumstances in which these coins were issued had been conditioned by the fact that Caesar had crossed the Rubicon on 11th January, causing the consuls named on the coin to abandon Rome. It is not clear whether the coins were produced in Rome but, if so, they would have represented the last to use bullion stored in the Aerarium Saturni before Caesar’s arrival in the City on 31st March. He spent only a few days there, before leaving for Spain in order to attack Pompey’s forces there. Amazingly, the fleeing consuls had left a large amount of bullion in the aerarium, and Caesar duly sent men to seize it before he left the City. The poet Lucan recorded that, when the plebeian tribune L. Caecilius Metellus saw that Caesar’s men:

“ ... [were about to use] force to burst open the temple of Saturn, he ... took is stand at the gates before the locks were broken. ... Dismal was the deed of plunder that robbed the temple, [after which], for the first time, Rome was poorer than a Caesar”, (‘Civil War’), 3: 115-8 and 167-8, translated by James Duff, referenced below, at p. 123 and 127).

by

An inscription (CIL X 6087) on the mausoleum of L. Munatius Plancus at Monte Orlando, Formiae records that:

L(ucius) Munatius L(uci) f(ilius) L(uci) n(epos) L(uci) pron(epos)

Plancus co(n)s(ul), cens(or), imp(erator) iter(um), VIIvir

epulon(um) triump(havit) ex Raetis, aedem Saturni

fecit de manibi(i)s, agros divisit in Italia

5 Beneventi, in Gallia colonias deduxit

Lugudunum et Rauricam

It records Plancus as consul (in 43 BC, the first full year of the triumvirate, when the triumvir M. Aemilius Lepidus was his consular colleague; censor,

twice proclaimed Commander-in-Chief,

member of the council of seven who have charge of sacrificial feasts,

It also notes that he:

triumphed over the Raetians,

founded the temple to Saturn with the spoils of war;

distributed land in Benevento in Italy; and

founded the colonies of Lugudunum (Lyon) and AugustaRaurica in Gaul.

According to Suetonius, Octavian/ Augustus (in addition to his own extensive programme of public works at Rome):

“... often urged other prominent men to adorn the City with new monuments or to restore and embellish old ones. Many such works were [undertaken] by many men at that time ... , [including] the temple of Saturn, by L. Munatius Plancus, [who triumphed ex Gallia in 43 BC] ...”, (‘Life of Augustus’, 29).

Reconstruction in the Late Republic

Detail of a relief (ca. 120 AD) found in the Forum, now displayed in the Curia Julia

Adapted from an image in Jeff Bondono’s website on the Roman Forum (scroll down to the Curia Julia)

My additions in red

A now-lost inscription (CIL 1316, ca. 40-22 BC) that was found near the temple recorded that:

L(ucius) Plancus L(uci) f(ilius) co(n)s(ul)/ imp(erator) iter(um), de manib(iis)

The information here is supplemented by another inscription (CIL X 6087) on the mausoleum of L. Munatius Plancus at Monte Orlando, Formiae, which records that:

L(ucius) Munatius L(uci) f(ilius) L(uci) n(epos) L(uci) pron(epos) Plancus/

co(n)s(ul), cens(or), imp(erator) iter(um), VIIvir /epulon(um)

triump(havit) ex Raetis, aedem Saturni/ fecit de manibi(i)s

agros divisit in Italia/ Beneventi, in Gallia colonias deduxit/ Lugudunum et Rauricam

I discuss this longer inscription in more detail below. For the moment, we should simply note that it confirms that L. Munatius Plancus (cos 42 BC, censor 22 BC) rebuilt the temple of Saturn, using part of the spoils from the Gallic campaign that led to his triumph over the Raeti as proconsul in 43 BC (in the aftermath of the murder of Julius Caesar).

Amanda Claridge (referenced below, p. 75) noted that the fragment of the relief illustrated above (her Figure 15), which is now displayed in the Curia Julia, depicts an emperor (possibly the Emperor Hadrian) presiding over the burning of what were probably records of public debtors, in front of the temple of Saturn (presumably in the form in which it had bee rebuilt by Plancus) and the temple of Vespasian and Titus. John North Hopkins (referenced below, at p. 144) attributed the ‘towering concrete podium’ of the surviving structure to this late Republican reconstruction.

Reconstruction in the Late 4th Century BC

As Amanda Claridge (referenced below, at p. 83) pointed out:

“The inscription [CIL VI 0937, late 4th century AD] on the [surviving] architrave reads:

Senatus populusque Romanus/incendio consumptum restituit

(Destroyed by fire, restored by the Senate and People of Rome)

The restoration took place in ca. 360-380 AD, [and represents] a significant manifestation of pagan revivalism amongst the politically disgruntled senators [at Rome in the late 4th century AD].”

The surviving eight columns have been reconstructed from elements that mostly date to this period.

Read more:

Pina Polo F. and Díaz Fernández A., “The Quaestorship in the Roman Republic”, (2019) Berlin and Boston

Patterson R. J., “E Lexico Sexti Pompeii Festi de Verborvm Significatv Selectiones: Selections from the Lexicon of Sextus Pompeius Festus, On the Meaning of Words: Translated with Introduction and Notes”, (2018) thesis of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario

Wilson M., "The Needed Man: Evolution, Abandonment, and Resurrection of the Roman Dictatorship" (2017) thesis of City University of New York

Ando C., “Mythistory: The Pre-Roman Past in Latin Late Antiquity”, in:

Leppin H. (editor), “Antike Mythologie in Christlichen Kontexten der Spätantike (Ancient Mythology in Late Antique Christian Contexts)”, (2015) ebook

Cornell T. C. (editor), “Fragments of Roman History”, (2013) Oxford

Kaster R. A. (translator), “Macrobius: Saturnalia (Vols. I-III)”, (2011), Cambridge MA

Hopkins J. N., “Genesis of Roman Architecture’, (2006) New Haven CT and London

Brennan T. C., Perrone, F. and Farney G., “Early Coinage of the Roman Republic (280 to 91 BC)”, (2005) New Brunswick, NJ

Claridge A., “Rome: An Oxford Archeological Guide”, (1998, 2nd edition 2010) Oxford

Coarelli F, “Il Foro Romano: Periodo Arcaico,” (1983) Rome

Richardson L., “The Approach to the Temple of Saturn in Rome”, American Journal of Archaeology , 84: 1 (1980), 51-62

Carettoni G. et al., (editors), “La Pianta Marmorea di Roma Antica: Forma Urbis Romae “, (1960) Rome

Kent R. (translator), “Varro: On the Latin Language, Vol. I (Books 5-7) and Vol. II (Books 8-10 and Fragments”, (1938) Cambridge, MA

Duff J. D. (translator), “Lucan: The Civil War (Pharsalia)”, (1928) Cambridge MA

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)