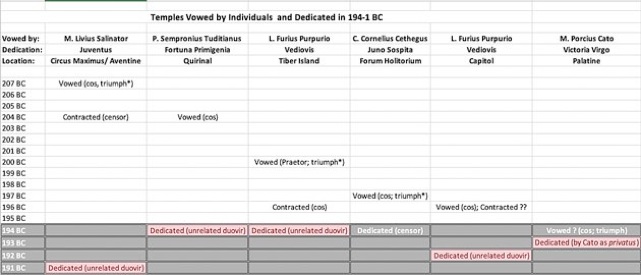

The four-year period (194 - 191 BC inclusive) saw the dedication of no fewer eight temples in Rome. Only two of these temples had been ‘public’ commissions:

-

✴the temple of Faunus on the Tiber Island, which was:

-

•commissioned in 197 BC by a pair of aediles in their official capacity; and

-

•dedicated in 194 BC by one of these aediles, when he was urban praetor; and

-

✴ the temple of Magna Mater on the Palatine, which was:

-

•built to house a black stone that represented the goddess that had been brought to Rome from Pessinus in Asia Minor (modern Turkey) after the consultation of the Sibyline Books; and

-

•dedicated in 191 BC by the urban praetor.

This page deals with the dedication of the other six of these temples, each of which had been vowed by a Roman commander.

Temples Vowed by a Roman Commander

For triumphs (*): see John Rich (referenced below, at p. 249)

Dedication in pink: made by a duovir who was unrelated to the commander who had vowed the temple

The period 194-1 BC saw the dedication of six temples that had been vowed by an individual who had held military imperium at the time:

-

✴three of these temples were dedicated in 194 BC:

-

•the temple of Fortuna Primigenia on the Quirinal, which had been vowed in 204 BC by the consul P. Sempronius Tuditianus during the later stages of the Second Punic War;

-

•the temple of Vediovis on the Tiber Island, which had been vowed in 200 BC by L. Furius Purpurio (as praetor) during an engagement with Gallic and Ligurian tribes in Cisalpine Gaul; and

-

•the temple of Juno Sospita in the Forum Holitorium, which had been vowed in 197 BC by the consul C.Cornelius Cethegus at the beginning of a battle in Cisalpine Gaul;

-

✴193 BC saw the dedication of the shrine of Victoria Virgo on the Palatine (see my page Palatine Temples of: Victoria (294 BC); Victoria Virgo (194 BC); and Magna Mater (191 BC)), which had been commissioned in 194 BC by the consul M. Porcius Cato and probably financed from booty gained in his Spanish campaign of that year;

-

✴192 BC saw the dedication of another temple of Vediovis, the temple of Vediovis on the Capitol: according to Livy, L. Furius Purpurio had vowed it as consul in 196 BC during another engagement with Ligurian tribes in Cisalpine Gaul; and

-

✴191 BC saw the dedication of temple of Iuventus on the Aventine, which the consul M. Livius Salinator had vowed in 207 BC during the Battle of Metaurus.

Temples that had been vowed by individual Roman commanders were often dedicated by the same individual in his next period in magisterial office. However, on some occasions, such dedications were made by duoviri aedi dedicandae, magistrates appointed for this purpose. Eric Orlin (referenced below, 1997, at p. 211) listed the eleven known duoviril dedications from the period from 509 to 55 BC:

-

*two of these (both in 215 BC) were made as duovir by the commander who had vowed the temple in question;

-

*three of them (one in 484 BC and the other two in 181 BC) were made as duovir by the son of the commander who had vowed the temple in question, after his father’s death; and

-

*five of them (one in 216 BC and the other four in the period 194-2 BC) had been made by duoviri who were unrelated to the commanders who had made the original vow.

The group of four dedications by unrelated duoviri in 194-1 BC (highlighted in pink in the table above) is obviously anomalous:

-

*it accounts for four of the five dedications of temples vowed by a commander in battle that were made by an unrelated duovir; and

-

*these four ‘unrelated’ duoviral dedications:

-

-accounted for four of the five dedications of such temples made in this four-year period (itself anomalous); and:

-

-related to temples that had been vowed over a period of sixteen years.

There are a number of possible reasons for this anomalous concentration of ‘unrelated’ duoviral dedications: for example. the temples of Salinator and Tuditianus had both been vowed during the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), and it is likely that their construction had been hampered by lack of funds after the war, and it is possible that one or both of them died without heir before his temple was completed:

-

✴M. Livius Salinator was last recorded as censor in 204 BC. He had at least one son, C. Livius Salinator (cos. 188 BC), but he served as naval praetor in the east in 191 BC (see John Briscoe, referenced below, at pp. 194-5 and Eric Orlin, referenced below, 1997, at p. 183 and note 72).

-

✴P. Sempronius Tuditianus was last documented as the leader of a Roman delegation to Greece in 201-199 BC, and there is no evidence that he had a son active in public life in 194 BC (see John Briscoe, referenced below, at pp. 57 and Eric Orlin, 1997, referenced below, at p. 184 and note 74).

However, L. Furius Purpurio was certainly alive when his temples were dedicated (in 194 and 192 BC): Livy (‘History of Rome’, 37: 55: 7) named him among ten ambassadors who were sent to Asia in 189 BC. I discuss the particular circumstances that might have led to the duoviral dedication of Furius’ temples below.

Temples Vowed by L. Furius Purpurio

Livy gave comprehensive, albeit internally inconsistent, accounts of the temples that Furius vowed as praetor in 200 BC and then as consul four years later:

-

✴In 200 BC, as praetor in command at the Battle of Cremona, he:

-

“... ... vowed a temple to Deoiove (sic), should he rout the enemy on that day”, (‘History of Rome’, 31: 21: 12).

-

Livy returned to this temple in his account of the events of 194 BC, when:

-

“... the duovir C. Servilius saw to the dedication on the Tiber Island of a temple to Iove [Jupiter], which had been vowed during the Gallic War by the praetor L. Furius Purpurio, who had subsequently contracted out its construction as consul”, (‘History of Rome’, 34: 53: 7).

-

✴In his account of the events of 192 BC, Livy recorded that:

-

“Two temples to Iove [Jupiter] were dedicated on the Capitol; L. Furius Purpurio had vowed [both of them]:

-

•one while praetor [in 200 BC], in the Gallic war; and

-

•the other while consul [in 196 BC].

-

The duovir Q. Marcius Ralla dedicated them”, (‘History of Rome’, 35: 41: 8).

Thus, if we take Livy’s accounts at face value, Furius vowed three temples in four years:

-

✴a temple dedicated to Deoiove (sic) or Jupiter on the Tiber Island, which:

-

•Furius:

-

-vowed as praetor in 200 BC (31: 21: 12); and

-

- commissioned as consul in 196 BC (34: 53: 7); and

-

•the duovir Caius Servilius dedicated in 194 BC (34: 53: 7); and

-

✴two temples on the Capitol, both of which were dedicated to Jupiter:

-

-one that Furius vowed as praetor in 200 BC (35: 41: 8); and

-

-another that he vowed as consul in 196 BC (35: 41: 8);

-

both of which were dedicated by the duovir Quintus Marcius Ralla in 192 BC (35: 41: 8).

John Briscoe (referenced below, at p. 113) argued that the passage at 35: 41: 8 is obvious wrong, since it is incredible that two separate temples on the Capitol, both dedicated to Jupiter, were each vowed by Furius and dedicated by Ralla in 192 BC. It seems to me that it is equally incredible that Furius, as a mere praetor in 200 BC, vowed two separate temples, one on the Tiber Island (31: 21: 12) and the other on the Capital (35: 41: 8). Briscoe suggested that the first step [in resolving these problems is to discount the claim made in 35: 41: 8 that Ralla dedicated two temples on the Capitol in 192 BC. On this basis, Furius vowed two temples:

-

✴In 200 BC, as praetor, Furius vowed a temple to Deoiove (sic) or Jupiter (31: 21: 12). He let the contract for the construction of the temple on the Tiber Island (34: 53: 7) and the duovir C. Servilius dedicated it in 194 BC. (34: 53: 7).

-

✴In 196, as consul, Furius vowed a temple to Jupiter on the Capitol (35: 41: 8), and the duovir Q. Marcius Ralla dedicated it in 192 BC (35: 41: 8).

Read more:

Davies P., “Architecture Politics in Republican Rome”, (2017) Cambridge

Rich J., “The Triumph in the Roman Republic: Frequency, Fluctuation and Policy”, in:

C. H. Lange and F. J. Vervaet (editors), “The Roman Republican Triumph: Beyond the Spectacle”, (2014) Rome, at p. 197-258

Carafa P. and Pacchiarotti P., “Regione XIV: Transtiberium”, in:

Carandini A. (editor), “Atlante di Roma Antica”, (2012) Rome: Vol. 1 pp 549-82; and Vol. 2, Map 247

Moreau H, “Entre Deux Rives- Entre Deux Ponts: l’ Île Tibérine de la RomeAantique: Histoire, Archéologie, Urbanisme des Origines au Vè Siècle après J.C”, (2014) thesis of Université Charles de Gaulle, Lille

Latham J., “Fabulous Clap-Trap”: Roman Masculinity, the Cult of Magna Mater, and Literary Constructions of the Galli at Rome from the Late Republic to Late Antiquity”, Journal of Religion,

92: 1 (2012) 84-122

Orlin E, “Foreign Cults in Rome: Creating a Roman Empire”, (2010) Oxford

Brennan T. (Corey), “The Praetorship in the Roman Republic”, (2000) Oxford

Gruen E., “Culture and National Identity in Republican Rome”, (1992) New York

Gruen E., “Studies in Greek Culture and Roman Policy”, (1990) Berkeley, Los Angeles and London

Briscoe J., “A Commentary On Livy: Books 31-33”, (1973) Oxford

Orlin E., “Temples, Religion and Politics in the Roman Republic”, (1997) Leiden, New York, Cologne

Scullard H., “Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic”, (1981) London

Kent R. (translator), “Varro: ‘On the Latin Language’: Volume I: Books 5-7”, (1938) Cambridge MA

Frazer J. (translator, revised by G. P. Goold), “Ovid: ‘Fasti’”, (1931), Cambridge MA

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)