Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temples of Mater Matuta and Fortuna at Sant’ Omobono

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temples of Mater Matuta and Fortuna at Sant’ Omobono

Archeological area beside the church of Sant’ Omobono (from Wikipedia)

Introduction

The fasti Antiates Maiores (ca. 60 BC) record that two temples:

✴one dedicated to Mater Matuta; and

✴the other to Fortuna;

had their dies natalis on 11th June, the date of the annual festival of the Matralia. Ovid (ca. 8 AD) discussed both of these cults in his ‘Fasti’ (a long poem on the Roman calendar, of which six books, covering January to June) survive. Ovid called on the ‘good mothers’ of Rome to attend the Matralia on 11th June and to:

“... offer to the Theban goddess [Ino, the daughter of Cadmus of Thebes, whom he equated with Mater Matuta - see below] the yellow cakes that are her due. It is said that, on this day, Servius [Tullius, traditionally Rome’s 6th king (578 - 535 BC)]... consecrated a temple to Mother Matuta in an open space of great renown adjoining the bridges and the Circus Maximus, which takes its name from the statue of an ox [i.e., the Forum Boarium] ... ”, (‘Fasti’, 6: 475-80, translated by James Frazer, referenced below, at p. 355).

In a later verse of this poem, Ovid exclaimed that:

“Fortuna:

✴the same day, [11th June];

✴the same founder, [Servius Tullius]; and

✴the same place, [the Forum Boarium];

are yours. But, who is that man hiding with togas flung over him? He is generally identified as King Servius, but the reason for this is uncertain”, (‘Fasti’, 6: 569-72, translated by James Frazer, referenced below, at p. 363).

Thus, at least by Ovid’s time, the temples of Mater Matuta and Fortuna in the Forum Boarium were regarded as ‘twin temples’ that had both been founded by Servius Tullius:

✴the temple of Mater Matuta was the locus of the Matralia; and

✴the temple of Fortuna housed a statue covered by togas that was said by some to portray Servius Tullius.

Literary Sources

Mater Matuta

Livy (ca. 25 BC) made no mention of either of these temples in his account of Servius’ reign, but he did refer back to the temple of Mater Matuta in his account of the appointment of M. Furius Camillus to his first dictatorship, when he was given command against the Etruscan city of Veii in 396 BC:

“[When] everything was in readiness for the campaign, Camillus vowed, in pursuance of a senatorial decree, ... Matutae Matris refectam dedicaturum (to restore and re-dedicate) the temple of Mater Matuta, which had previously been dedicated by King Servius Tullius”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 19: 6).

Plutarch (ca. 80 BC) , who probably relied on Livy here, similarly recorded that, immediately after his appointment as dictator in 396 BC, Camillus:

“... made solemn vows to the gods that, if the war [with Veii] had a glorious ending, he would celebrate the great games in their honour and dedicate a temple to a goddess whom the Romans call Mater Matuta”, (‘Life of Camillus’, 5: 1).

Livy then recorded that, after Camillus had taken and destroyed the city of Veii, he celebrated a triumph in which:

“...he rode into the City [in triumph and then, inter alia], dedicated a temple to Mater Matuta”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 23: 7).

Fortuna

Dionysius of Halicarnssus (ca. 7 BC), who did not record Servius’ dedication of the temple of Mater Matuta, did record that, just before his death, Servius:

“... built two temples to Fortuna, who seemed to have favoured him all his life:

✴one in the market called the ‘Cattle Market’ [i.e., the Forum Boarium]; and

✴the other on the banks of the Tiber, to ... Fortuna Virilis (as she is called by the Romans even to this day)”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 4: 27: 7).

The second of these temples was probably upstream, on Via Portuensis (which ran along the right bank of the Tiber to Portus), at either the 1st of the 6th milestone.

Reconciliation with the Archeological Evidence from Sant’ Omobono

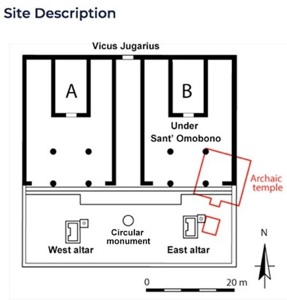

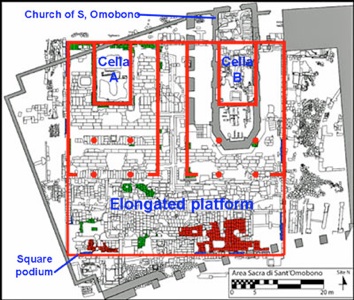

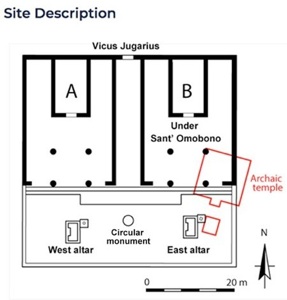

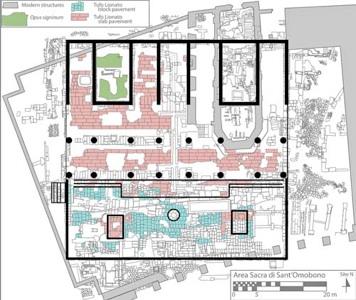

Temples at Sant‘ Omobono in ca. 500 BC (from the plan in the site of the Sant’ Omobono Project)

Archaic temple and altar in red

The remains of a single archaic temple and a pair of early Republican temples (marked Temples A and B on the plan above) were discovered in 1937, when the area surrounding the church of Sant’ Omobono was being cleared for development. Since this site would have been on the northern fringe of the Forum Boarium, Temples A and B were quickly identified as the temples of Mater Matuta and Fortuna known from the literature. Another six excavation campaigns were carried out in the period to 1986, but all of these campaigns were limited in both time and extent and further hampered by the proximity of the site to the Tiber. A concerted programme known as the Sant’ Omobono Project was launched in May 2009 by the Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali, the Università della Calabria and the University of Michigan, and this has given rise to a series of publications that:

✴analysis of the results of the earlier campaigns as represented in the surviving records; and

✴report on the new excavations, which involve the sophisticated techniques that a site like this demands.

However, our understanding of the site inevitably remains incomplete, not least because the presence of the church and other neighbouring buildings restricts the area available for excavation. As we shall see, these campaigns have established that:

✴At least one temple (outlined in red on the plan above) was built here in the early 6th century BC and rebuilt in ca. 530 BC, and, although there is no evidence of the existence of a second ‘twin’ temple from this period, this possibility cannot be excluded.

✴This archaic temple and its putative twin were demolished in ca. 500 BC and twin temples (Temples A and B on the plan above) were built at a higher elevation on an adjacent (and partially overlapping) site shortly thereafter.

✴These temples were rebuilt on the existing ‘footprint’ in ca. 300 BC and again after a fire that (according to Livy, see below) occurred in 213 BC.

We can reasonably assume that the authors quoted above who recorded Servius Tullius’ traditional activity on this site (i.e., Livy, Dionysius and Ovid) knew nothing of the archaic temple(s): they almost certainly assumed that Servius had founded and dedicated Temples A and B. (Unfortunately, none of our surviving sources indicate which of these was dedicated to Mater Matutaa and which to Fortuna).

The uncertainty about whether a second archaic temple ever existed on this site complicates the process of reconciling the archeological and the literary evidence:

✴If this putative second temple has yet to be discovered, then there would be no problem in identifying these as two archaic temples as temples of Mater Matuta and Fortuna, both of which were traditionally held to have been founded by Servius Tullius.

✴However, if only a single archaic temple (marked in red on the plan above) ever existed here, then:

•Livy’s testimony (at 5: 19: 3) would suggest that it was dedicated to Mater Matuta and traditionally founded by Servius Tullius; and

•Dionysius’ testimony that Servius had dedicated a temple to Fortuna here would represent a later development of the tradition.

That leaves the testimony of Livy (and the possibly derivative testimony of Plutarch) that Camillus had rebuilt and re-dedicated the temple of Mater Matuta in 396 BC. The problem here is that, as mentioned above and discussed further below, the detailed archeological evidence points to:

✴the initial construction of Temples A and B in ca. 500 BC; and

✴a single significant rebuilding of both temples in a single project at some time after ca. 300 BC.

Of course, it is possible that Camillus restored the Temple of Mater Matuta in 396 BC without leaving any clear evidence in the archeological record. I discuss this possibility below after a detailed look at the published archeological evidence for the evolution of the site from the Regal period until the fire of 213 BC.

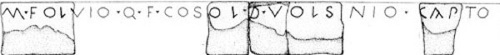

Finally, as we shall see, there is clear epigraphic evidence in the archeological record that indicates that M. Fulvius Flaccus made a dedication here as consul in 264 BC, after he had captured the Etruscan city of Volsinii, although this dedication is not recorded by any of our surviving sources. As we shall see, it is possible that Flaccus was more comprehensively involved in the rebuilding of Temples A and B that the archeologists date to ca. 300 BC.

Archaic Temple(s) at Sant’ Omobono

Topography of the Site in the Archaic Period

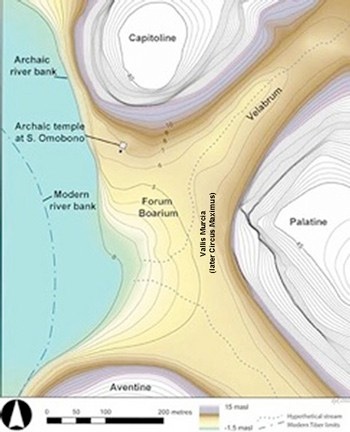

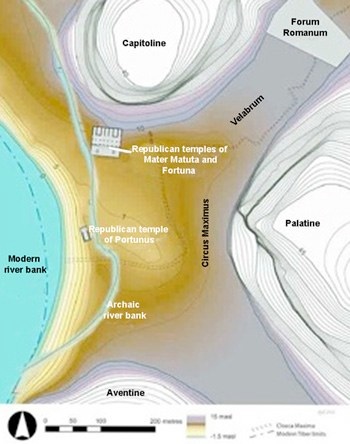

Topographic reconstruction of the early archaic riverbank in the Forum Boarium

Adapted from Andrea Brock, Laura Motta and Nicola Terrenato (referenced below, at fig. 4, p. 11)

Andrea Brock et al. (referenced below) recently published the results of a coring survey of the Forum Boarium, in which they established the archaic topography of the area (which they summarised at p. 17 and illustrated in the figures reproduced above). Their analysis revealed that the archaic temple under the church of Sant’ Omobono had been built on a natural ledge below the Capitol, at 6.5 masl (meters above sea level). Furthermore, this temple originally stood on:

“... a 1.7 m high podium made from an unusually dense variety of tufo lionato imported from the Anio region that would have been more resistant to water damage than local stone, [which] further lifted the temple’s vulnerable superstructure to an elevation of 8.2 masl. For comparison, ... the first gravel surface of the nearby Forum Romanum [at the north eastern border of the Velabrum], where an archaic land-reclamation project filled the valley,... raised the ground level [there] to 8.6 masl. These two elevations provide a strong indication of the height [that had been] perceived to be ‘safe’ [from flooding] in the early 6th century BC. ... [Furthermore], our investigations have documented pre-Republican flood deposits only as high as 7.4 masl, this being the upper limit of the land surface beneath the Sant’ Omobono sanctuary. ... We suggest that, at the time that the harbour temple was built, a flood reaching more than 8 masl would have been an exceedingly rare event. It [therefore] seems that Rome’s first monumental temple ... was erected in a position that was highly visible as well as offering relative safety from inundations.”

These authors made three other important observations (at pp. 14-5):

✴“[This] low-lying shore would have been an ideal location for animals to drink at the river. Indeed, ancient sources and generations of modern scholars have made etymological inferences about the origins of the Forum Boarium as a cattle market. Livestock that would have had difficulty traversing the steep terrain typical of other sections of riverbank would have been able to approach the river at this particular point with far greater ease. Although we must be cautious not to extrapolate broadly from findings from a single core, a borehole drilled near the south-east corner of the Sant’ Omobono sanctuary exposed ... 40 cm of animal dung, suggesting that livestock were present in the archaic Forum Boarium. It is difficult to know the scale of ... [the putative] cattle market, but the availability of suitable terrain [for grazing and watering] would certainly have influenced the way that livestock in early Rome were maintained and shepherded across the landscape”.

✴“Second, there is new justification for the notion of a ford at this gently sloping shore ... , [albeit that], contrary to earlier speculation, a crossing point would not necessarily have relied on slack water created by the Tiber island; it is actually possible that the island did not even exist in this era. ... The available geoarchaeological evidence [for a ford at this point], while not definitive, is nonetheless strongly suggestive of the conditions necessary for a ford. Moreover, rivers tend to become deeper as they approach the sea, so is it possible that the first available ford for travellers coming up from the coast was at the site of Rome. Such a crossing point would have served as a vital nexus for regional transhumance routes and funnelled the movement of people and livestock between Etruria and Latium”.

✴“Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the natural topography created conditions suitable for a year-round harbour at the lowest point of the valley. Drawing on ethnographic comparisons in conjunction with archaeological and literary evidence from across the Mediterranean, it is apparent that prehistoric harbours did not require infrastructural investment, ... [since] many seafaring boats were sufficiently lightweight and flat-bottomed to be hauled ashore by a team of men. Importantly, such flat hulls could navigate the shallower waters of a river and even be propelled upstream by rowing, towing and/or push-pole. ... Although previous reconstructions of the Forum Boarium valley with a swamp or a high riverbank have led to the conclusion that the site was not suitable as a landing for boats, these notions can now be ruled out: the low shore where the Velabrum met the Tiber would in fact have been an ideal landing for boats, permitting the loading and unloading of cargo as well as the performance of maintenance”.

In short, the temple overlooked a coastal site that was ideally placed for riverine and agricultural commerce and would have been frequented by merchants and seamen from across Italy and beyond. Moreover, as Andrea Brock and her colleagues also noted (at p. 15), there is proof of these putative activities: the excavations of 1937 that had led to the discovery of the remains of the archaic temple had:

“... also produced an impressive ceramic assemblage of Bronze Age, imported Greek, and Early Iron Age Etruscan wares, ... mixed in secondary contexts at the ... sanctuary. Drawing on these archaeological discoveries, ... scholars began writing of a commercial port that stretched back to the prehistoric era. The presence of orientalising Greek pottery, in particular, led to the conclusion that foreign trade via Rome’s harbour began already in the 8th century.

They concluded (at p. 17) that this archaic temple looked down on:

“... a critically important liminal zone in Rome, where locals could interact with foreigners and neighbours.”

Phase I of Construction

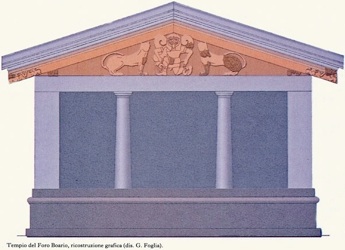

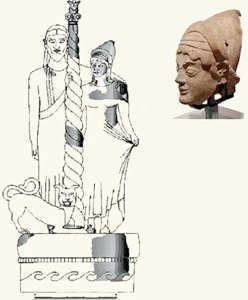

Reconstruction of the original temple under Sant’ Omobono

From Anna Mura Sommella (referenced below, 2000, at Fig. 1, p. 9)

Remains, probably from the original temple pediment, exhibited in the Musei Capitolini

Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at pp. 11-2) gave a detailed description of the surviving archeological evidence for this archaic temple, which came from predominantly from the remains of its roughly square podium (ca. 10x10 meters), about a quarter of which has been reached by excavation since 1937. It was approached from the south by a frontal staircase some 2 meters wide, which comprised seven steps, of which the lowest and an imprint of the one above it survive. They noted (at p. 13) that the foundations of the altar that stood in front of the temple survive, and that these:

“... suggest that it faced east, in common with the later, Republican altars at the site [see below]”.

They also observed (again at p. 13) that relatively few of the architectural terracottas that have been found at the site can be attributed to the decoration of the first-phase temple:

“These include:

✴plaques in relief representing heraldically-opposed semi-crouching felines, possibly flanking a central Gorgon figure, which would have filled a closed pediment (a Greek element that is otherwise unknown in Italic temple architecture); [and]

✴revetment plaques bear felines in relief processing up the pediment rafters, which, together with the remains of pedimental revetments, attest a roof slope of 21°.25.”

These terracotta fragments are exhibited in the Musei Capitolini, as illustrated above. They cautioned (at p. 12) that the evidence for the other components of the temple is quite limited, despite the fact that ‘reconstructions’ of it that sometimes appear in the literature, where it :

“... is usually reconstructed as a ‘distyle in antis’ Tuscan type, with closed alae [wings] flanking a single central cella, but evidence for most of these features is limited: even the columns [in these reconstructions] are not structurally necessary. Part of a foundation for the cella was documented [by one of the earlier excavators], but it is not possible to say whether this was flanked by closed rooms or open passages.”

In relation to the dating of the original temple, Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at pp. 13-4) observed that:

“ The latest datable ceramics ... in deposits immediately underlying the temple foundations give a terminus post quem within the first quarter of the 6th century BC, while the profile of the podium moulding finds parallels in early to mid-6th century tombs at Caere. The subject and arrangement of the sculptures from the [original temple pediment] parallel the pedimental sculpture of the Temple of Artemis on Corfu, dated ca. 580 BC. These dates are consonant with the earliest Greek pottery ... deposited in association with the temple. The construction of the first-phase archaic temple, then, can be comfortably dated to ca. 585-575 BC ...”

They observed (at p. 20) that this temple:

“... certainly represents the earliest stone temple known from Rome, preceding the inauguration of the massive Temple of Jupiter [Optimus Maximus on the Capitol] by a couple of generations. Its creation can be seen in the context of the emporic cults appearing around the Mediterranean at this time ...”

Paolo Brocato and Nicola Terrenato (referenced below, at p. 104) similarly concluded that the temple was:

“... built and completed well before the middle of the [6th century BC], making it the earliest temple building so far discovered in Rome. ... [There] can be little doubt that [it] was inaugurated at least a half century before [the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitol.]”

Existence of an Archaic Twin ?

As noted above, Ovid believed that Servius Tullius had dedicated two temples on this site (one to Mater Matuta and the other to Fortuna) on the same day. However, as we shall see, the twin temples that were dedicated to these deities in the Republican period date to ca. 500 BC. It is possible that the archaic temple under discussion here had a twin: as Paolo Brocato and Nicola Terrenato (referenced below, at p. 105) observed, although there is no evidence for this, the possibility cannot be ruled out given the limited area of the site that has been excavated to date. They suggested that:

“The most likely area [for such a structure] would be between the twin [Republican] temples, where, however, the presence of later structures ... makes any extensive excavation impossible.”

The bottom line is that:

✴we have no evidence apart from literary sources from the late Republic or thereafter for a second archaic temple on the site; and

✴no basis for establishing whether the archaic temple that certainly existed here in the early 6th century BC was dedicated to either Mater Matuta or Fortuna.

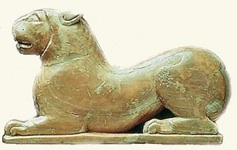

Votive Object

Ivory lion plaque (early 6th century BC), now in the Musei Capitolini

Drawing of the reverse of the plaque, with its inscription identifying Araz Silqetenas Spurianas

From Nicola Terrenato (referenced below, 2019, at p. 55, Figure 2.7)

This ivory lion plaque (early 6th century BC), which was found among the votive deposits on the site, bears one of the earliest Etruscan inscriptions from Rome. It is interpreted as a tessera hospitalis (token of mutual hospitality) and an inscription on the back commemorates Araz Silqetenas Spurianas. The name Arath Spuriana is inscribed above the frescoes on back wall of the so-called Tomb of the Bulls (ca. 525 BC) at Tarquinia (see John Oleson, referenced below, at p. 192, not 19 and Fig. 3). On this basis, Giuliano and Larissa Bonfante (referenced below at p. 31) characterised the man commemorated on the lion as:

“... a noble from Tarquinia, [who was] a resident of Rome at the moment of the traditional installation of the Etruscan dynasty [there].”

Phase II of Construction

Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at pp. 14-6) observed that:

“At some time in the 2nd half of the 6th century BC, the [original temple] podium was remodelled, ... [and] new moulding ... seems to have been added ... [Recent analysis suggests] that the [original] moulding blocks (if they were ever present) must have been removed before the collapse of the temple superstructure, [which] implies that the second-phase podium moulding was not a load-bearing element. The foundations of the cella proper also seem to have been rebuilt, and a torus block from the first phase was deposited as fill between the exterior of the podium and the W cella wall. ... The reconstruction of the cella foundations suggests that the E–W width of the cella itself, and hence the central axis of the temple, remained the same as in the first phase. Basing any more detailed reconstructions on the exiguous remains becomes extremely risky.”

Paolo Brocato and Nicola Terrenato (referenced below, at p. 101) similarly observed that, while scholars assert that a second phase of construction involved:

“... a massive reworking of the whole [of the original] podium in the course of the 6th century BC, ... the evidence for this is more limited than is generally realised, and many doubts remain about the actual nature and extent of the modification.”

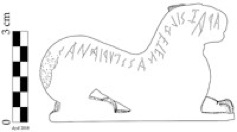

Roof System of Phase II

Remains from Sant’ Omobono exhibited in the Musei Capitolini, probably from the re-modelled archaic temple

One aspect of the remodelling of the archaic temple is reasonably well-attested: as Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at p. 16) pointed out, at some point, it received a new terracotta roof-system that:

“... was a hybrid system of Corinthian pantiles painted with red and black hourglass patterns and semi-cylindrical cover-tiles, with a slope of 18°.44. The ends of the eaves were protected by simas [upturned edges] with female heads and lion-head water spouts. The roof also included:

✴an acroterial figural group at three-quarters life-size, generally identified as Hercules and Minerva [illustrated and discussed below];

✴at least two winged sphinx corner acroteria;

✴at least four acroterial volutes; ... [and]

✴revetment plaques of the Veii–Rome–Velletri ... type along the pediment [illustrated above and discussed below].

The same mould was used for the face of ‘Minerva’, the sphinxes and the antefixes. Although the ‘Hercules and Minerva’ are usually reconstructed as standing at the front of the temple’s central ridge, the fragments of the group were all found northwest of the temple, ... [near] one of the structure’s back corners.”

Nancy Winter (referenced below, at pp. 198-9) observed that this roof, as re-modelled:

“... conforms to a decorative system [that is] known as the Veii-Rome-Velletri [V-R-V] system because 14 terracotta roofs from these [three] sites and from sites nearby them carried decoration made from the same series of moulds: [these decorations consisted] of:

✴figural revetment plaques with scenes of chariot processions, chariot races and horse races; and

✴lateral simas with feline-head water spouts, with cut-out openings at the sides for antefixes with female head.

Daniel Diffendale el al. (referenced below, at pp. 16-9) observed that:

“ Dating this second roof is another difficult business. Relatively secure is a terminus ante quem of the late 6th century BC, [which is] provided by the latest datable pottery in the destruction deposits of the temple. A deposit of votive materials resting against the north face of the podium, previously held to provide either a terminus ante quem for the first phase or a terminus post quem for the second, should probably be understood as a secondary dump following the destruction of the second phase [see below], and so cannot be put to chronological use. ... The V-R-V decorative system as a whole has been dated to ca. 530 BC, on the basis of stylistic comparanda with Etruscan Black Figure vase-painting of the Pontic Group, tomb-paintings, sculpture, and bronze-laminated furniture. Some have also drawn a connection between the temples decorated with V-R-V roofs and the career of Tarquinius Superbus (traditionally 534-509 BC). A slightly later modification, probably only partial, of the terracotta system on the Sant’ Omobono temple is indicated by three fragments of revetment plaques of the ‘Rome–Caprifico’ type, a variant of the V-R-V system, [which was] probably executed by the same workshop and dated to ca. 520 BC.”

Paolo Brocato and Nicola Terrenato (referenced below, at p. 105) similarly observed that the new revetment of the podium can probably be dated to:

“... around 540 BC ... , which fits well with that of the second phase of terracottas. It is thus probable that the modification of the podium was accompanied by a rebuilding of the roof, which was covered at this point with tiles made of impasto chiaro sabbioso. ... The renovation marked by [this] second phase ... is clearly a component of the overall restructuring of archaic Rome. ... Dressed in new, fancier ornaments of stone and terracotta, the temple ... [would have been] even more effective in welcoming travellers to a city that, at this point, [had] completed the first major development stage of its long evolution and growth.”

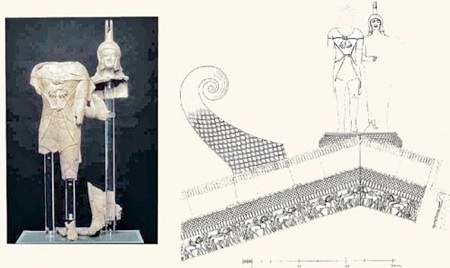

Left: remains in the Musei Capitolini, probably Hercules and Minerva, from the roof of the re-modelled temple

Right reconstruction by Nancy Winter (referenced below, 2018, as Fig 6, p. 199), drawn by Renate Sponer-Za

Nancy Winter (referenced below, at p. 199) observed that, among the known V-R-T roofs:

“The Sant’ Omobono roof preserves best an impressive group of Herakles and Athena [Roman Hercules and Minerva], standing ca. 1.20 m tall, mounted on an elaborately decorated base and placed at the apex of the roof, between two immense volute acroteria decorated with a painted scale pattern. Similar pairs of Herakles and Athena statues and volute acroteria have also been found in more fragmentary condition:

✴at Veii, Cerveteri and Pyrgi in Etruria; and

✴at Velletri, Satricum and Caprifico di Torrecchia in Latium.”

Left: remains (shaded) exhibited in the Musei Capitolini, probably from the roof of the re-modelled temple,

as reconstructed by Anna Mura Sommella (referenced below, 2017 as Fig 5, p. 111) and drawn by Patricia Lulof

Right: female head from the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen (from the photograph in the museum)

Anna Mura Sommella (referenced below, 2017, at p. 107) reported that the temporary transfer of the female head illustrated on the right above from the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen to the Musei Capitolini:

✴allowed it to be securely associated with other terracotta fragments from the site at Sant’ Omobono; and

✴supported the hypothesis that all of these fragments belonged to a second group made up of two figures, one male and the other female standing side by side, reflecting the group formed by Hercules and Minerva [illustrated above].

She argued (at p. 108) that the probable presence of a reclining panther in this composition allows the male figure to be identified as Dionysus and suggested that the female figure was Ariadne. Nancy Winter (referenced below, at p. 200) observed that:

“A second acroterial group and elaborately decorated base from Sant’ Omobono have recently been reconstructed from fragments, depicting a draped male figure and a female figure wearing the Etruscan pointed hat called a tutulus and pointed Etruscan boots known as calcei ripandi. The male figure has his left arm around the female figure, his hand on her left shoulder, and the female holds a staff. The feline attached to the base would appear to identify the male figure as Dionysos, but the identity of the female figure is less certain:

✴[Anna] Mura Sommella has suggested Ariadne [see above]; but

✴[Patricia] Lulof prefers Ino-Leukothea or Semele, Dionysos’s aunt [reference needed].

A similar statuary group preserving a male hand on a female shoulder comes from Cerveteri, although in mirror image to that from Sant’ Omobono.”

In summary, it seems that the ‘‘new’ roof of the archaic temple under Sant’ Omobono reflected the general material culture of Etruria and Latium in the 6th century BC and may have been at least partly responsible for it. The presence of figure groups of Hercules/Athena and Dionysius/?Ariadne do not unequivocally indicate the dedicant of the restored archaic temple under the church of Sant’ Omobono, although Nancy Winter (referenced below, see for example the captions to her figures 6 and 7) assumed that it was Mater Matuta, presumably because (as she observed at pp. 203-4), the broadly contemporary Temple of Mater Matuta at Satricum carried four pairs of life-sized statues of Greek gods/ goddesses, one of which represented Hercules (?)/ Athena.

Destruction

Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at pp. 20-1) observed that:

“ The archaic temple went out of use at the end of the 6th century BC. Black discolouration encountered during excavation has been interpreted as evidence of destruction by fire, but this may be a misinterpretation of natural concretions. The latest datable materials in these deposits are fragments of Attic Black Figure of the late 6th century BC. Votive materials were dumped against the back wall of the podium at some point before the superstructure collapsed. ... The presence of residual impasto bruno sherds that predate the construction of the temple, however, suggests [that this was] a secondary deposition. On stratigraphic considerations, the deposit seems to have been dumped before the mudbrick superstructure collapsed or was levelled. Although the material generally does not postdate the 3rd quarter of the 6th century BC, some of the bucchero could date as late as ca. 500 BC].”

This raises the question of why the temple was destroyed within about 30 years of a major remodelling. It is possible that the new roof:

✴compromised the structural integrity of the temple; and/or

✴was closely associated with Tarquniuius Superbus, causing the temple itself to fall out of favour after his expulsion in 509 BC.

However, we must also consider the fact that (as we shall see) Temples A and B were soon built at a significantly higher elevation on an adjacent and overlying site, which might suggest that hydrological factors were also important in driving this fundamental change to the cult site.

Hydrological Considerations

Topographic reconstruction of the mid-Republican riverbank in the Forum Boarium

Adapted from Andrea Brock, Laura Motta and Nicola Terrenato (referenced below, at fig. 8, p. 21)

Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2017, at p. 208) pointed out, the construction of the new podium in ca. 500 BC allowed for the:

“... raising [of] the level of the sanctuary well above the elevation of the archaic temples and above the likely line of minor floods of the Tiber.”

As I mentioned above, it is possible that the decision to demolish the archaic temple and replace it with Temples A and B was, in part, taken because of hydrological factor of the kind.

Andrea Brock, Laura Motta and Nicola Terrenato (referenced below, at pp. 17-8) observed that the results of their coring survey of the Forum Boarium indicated that:

“ Over the course of the 6th century BC, Rome’s fluvial system became unstable, and the river valley began a significant transformation. ... Regardless of the precise reasons for the river’ s movement, the hydrological and topographic changes in the Forum Boarium valley are apparent. ... As the area filled with fluvial sediments, the ground level was raised and extended westward over time: a high, wide riverbank emerged in the valley between the Capitoline and Aventine Hills.”

They noted (at pp. 25-6) that:

“... fluvial sediment was deposited [in this valley] at least into the 3rd century BC; only then, it seems, was the area extensively paved or built up. Although this area along the river had certainly been a major hub of activity since the beginning of sedentary habitation at the site, the significant degree of landscape change and land inflation in the river valley suggests that human activities must have been ephemeral or supported with limited built infrastructure (with the exception of the Sant’ Omobono sanctuary) until the3rd century BC. Both the archaeological and literary records confirm that the Romans made major investments in the Forum Boarium in the mid-Republic, reinforcing the riverbank and limiting further changes to the fluvial topography. Excavations at the Temple of Portunus [marked on the plan above] and the [nearby] Round Temple have revealed that both structures rest atop embankment walls, which were constructed sometime between the late 4th and early 2nd centuries BC. This broadly reflects the western edge of the siltation and the newly established position of the riverbank. The course of the Tiber river as it flowed through Rome became relatively static thereafter.”

It is unclear how far the river had moved in the last three decades of the 6th century BC and how the flood risk to the archaic temple had increased in this period. Nevertheless, it seems possible that the decision to build Temples A and B so soon after the re-modelling of the archaic temple was driven in part for the need to raise the elevation of the cult site, in order to:

✴improve visibility from the moving river bank; and

✴reduce the risk of flood damage.

Temples A and B to 213 BC

Republican Podium

Plan of the Republican podium and Temples A and B after the first phase of their construction

From Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2017, at p. 101, Figure 26) , my additions in blue

Elongated Platform

According to Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at pp. 21-2):

“At some point following (and probably soon after) the final destruction [of the archaic temples in ca. 500 BC], an elongated platform ... , the function of which is uncertain, was set [on a west-east axis] along what is now the southern edge of the site. ... It may have been built as a first retaining wall for the [subsequent] construction of the large podium [see below. Since] it survives in precisely the area where the later [west and east] altars would be placed, ... [it] could have supported altars for the ritual needs of the cult following the destruction of the earlier [monuments, although] this remains speculative.”

Square Podium

Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at pp. 22-3) then recorded that, very soon after the construction of this platform:

“... [and] still in the decade on either side of 500 BC, the area north of it and west of the archaic temple saw a massive transformation. A large square podium ... , [outlined in red on the plan above], measuring some 47 m per side, was raised some 3-5 m in height (the elevation of the underlying topography varies) ... The east foundations of this [podium] were cut into the clay levelling fill, sealing the remains of the archaic temple; its lowest courses here lie directly on the first-phase [archaic] podium. The two structures differ in orientation by ca. 18°, with the Republican podium oriented closer to true north ... .”

In order to date this Republican podium, Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at p. 24) observed that:

“The latest datable material in the deposits associated with the archaic temple ... [and the] latest datable material in the fill of the overlying Republican podium also dates to the late 6th century BC.”

John North Hopkins (referenced below, at p. 149) stressed the point that, among the many ancient objects that were found in 1937 and in the subsequent published excavations in the vast amount of fill under the elevated Republican podium:

“... not one fragment [among the dateable material] dates to after the 6th century BC. Recent and on-going investigations of previous [these] excavations as well as new soundings have found the same situation, with materials deposited in layers of both fill and foundation tranches for walls and pillars of the twin temples [that were subsequently built on the podium] dating to no later than the end of the 6th century BC.”

This certainly indicates that the surface of the Republican podium was effectively sealed in ca. 500 BC, soon after the destruction of the archaic temple.

Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at p. 27) observed that:

“The nature of the pavement of the Republican podium in this first ... phase is not clear. The ... pavement that currently occupies most of the temples’ porch post-dates this first phase, as it rests in part on the... foundations of the ... cella [of Temple A] and overlies the ... foundations of the first-phase alae. Although there is no positive evidence of an earlier stone pavement, excavation in areas where the [later] pavement is missing has documented the presence of several strata interpreted as preparation layers for earlier pavement(s).”

Phase I of the Construction of Temples A and B (ca. 500 BC)

Floor plan of the temples at Sant‘ Omobono in Phase 1 (from the plan in the site of the Sant’ Omobono Project)

Archaic temple and altar in red

As we have seen, the Republican podium was almost certainly sealed in ca. 500 BC (albeit that the nature of the pavement that must have covered it is unclear). As Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at p. 25) observed, by this time, this pavement covered the newly-laid:

“... foundations for two south-facing temple cellae, probably identical in plan:

✴the ...cella [of Temple B] ... lies beneath the later church of Sant’Omobono, for which reason little can be said about its earliest phases; but

✴the ...cella [of Temple A] ... has been the subject of investigation by our project between 2011 and 2015, offering much more information on its construction phases.

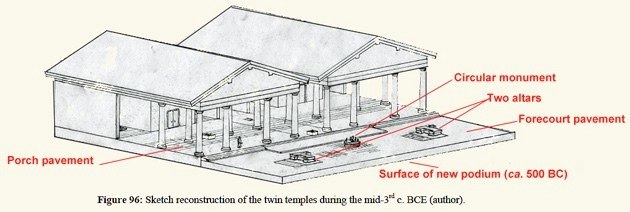

According to Nicola Terrenato (referenced below, 2016):

“The foundations inside the [Republican] podium make it clear that it supported two identical temples side by side, with two rows of two columns each on the front. Nothing remains of these temples, of their decoration, or of associated votive materials. ... They represent the earliest instance of twin temples sharing the same podium, and they begin the process of monumentalisation of the market area.”

Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2017, at p. 208) similarly recorded that:

“The temples in this phase were distyle in antis, with two rows of columns, and with closed alae [wings] flanking central cellae.”

It is usually assumed that, in this phase, the long walls of the alae completely enclosed the respective temples (as in the plan above).

Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, at p. 219) argued that, given the fragmentary nature of the archeological evidence at his time of writing (1988/92):

“... the attribution to Camillus of the podium with the twin temples seems to me the most acceptable (or, if you prefer, the least unacceptable) hypothesis”, (my translation).

In other words, Coarelli privileged the testimony of Livy (above) that associated Camillus with a temple to Mater Matuta in 396 BC. However, as further archeological evidence has emerged, it has become increasingly clear that the absence of dateable objects later than ca. 500 BC makes it almost certain that the podium and temple foundations existed by ca. 500 BC. It is, of course, possible that the temples themselves remained incomplete until the early 3rd century BC. However, as John North Hopkins (referenced below, at p. 151) observed, the completion of the podium had:

“... created a massive shelf off the southwestern corners of the Capitoline Hill, with ... its front projecting five meters above the natural ground level. Thus, on all sides, and especially from the front, the temples [when completed] and their platform loomed high above the surrounding area.”

Since the work below the platform would have represented the most challenging part of the construction project, it is hard to see why the next phase would be delayed for a century or so.

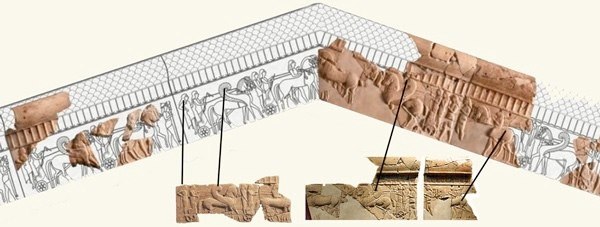

Two painted terracotta revetments (shaded) found at Sant’ Omobono in 1938 (now lost)

displayed against a drawing of a relief from the Acropolis Temple at Ardea (ca. 500 BC)

From John North Hopkins (referenced below, p. 150, Figure 117)

John North Hopkins (referenced below, at p. 149 and note 70) argued that the discovery of the two revetments illustrated above provide supporting evidence: although the context in which they were found is unclear, they can be dated by means of the larger fragment of a frieze from Ardea (illustrated above), which can be dated to the early 5th century BC. He concluded that the growing body of archeological evidence:

“... suggests that [the Romans] quickly rebuilt and paved the platform .... and, over the coming decades, they built two large twin temples capped with terracotta roofs [and] sporting a novel style of double-anthemion reliefs.”

This hypothesis now seems to represent the consensus opinion (see, for example: Penelope Davies, referenced below, at p 15 and note 56; Daniel Diffendale et al., referenced below, at pp. 23-4; and Seth Benard, referenced below, at p. 69 and note 96).

Temple Forecourt (4th - 3rd centuries BC)

Pavements of the Republican temples

Turquoise = block pavement within the temple forecourt

Pink = slab pavement, mostly within the temple porches

From Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2017, at p. 118, Figure 32)

According to Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2017, at p. 116)

“The earliest pavement [on the site] that can probably be dated to the middle Republic is a surface of the forecourt in front of the twin temples [designated ‘elongated platform’ in the discussion of the podium above]: resting directly on the blocks of the Tufo del Palatino structure [of the platform] is a pavement composed of a single course of Tufo Lionato blocks.”

Diffendale noted (at p. 121) that:

“[This] paving cannot currently be directly dated. Stratigraphically,

✴it rests on the Tufo del Palatino structure [of the platform, which] probably of early 5th century BC; and

✴ is overlain by the staircase and platform associated with the [pavement of the temple porches, in pink on the plan above, which should ] probably to be dated to the first half of the 3rd century BC [see below].

The [forecourt] pavement ... should [therefore] date between the 5th-3rd centuries BC. ... Certainly associated with at least part of [its] uselife are the two ... [rectangular] altars and the circular monument [indicated on the forecourt in the plan above]. Evidence suggests that these were later additions to the pre-existing pavement.”

However, in his summary of the construction phases (at p. 208) the down-dated the laying of the forecourt pavement:

“At some point in the 4th or 3rd century BC, the forecourt of the Republican podium was paved with blocks of Tufo Lionato ... This phase could possibly be connected with the ancient notices on the dedication of the temple of Mater Matuta by M. Furius Camillus in the early 4th century BC, but this is not at all certain.”

I discuss this possibility further below.

Phase II of the Construction of Temples A and B (ca. 300 BC)

Reconstruction of the twin temples during the mid 3rd century BC

as deduced by Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2017, Fig. 96, at p. 208: my additions in red)

According to Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at pp. 28-9):

“ A reconstruction of the twin temples is attested by [the slab] pavement [marked in pink on the plan above] ... that surrounds the cella [of Temple A] on three sides and is preserved south of the ... cella [of Temple B], forming the floor of the temples’ porches ... . [If, in their first phase, the] temples had closed alae [wings along cella and pronaus], as seems likely, that was no longer true of the structures of which this [slab] pavement was a part, since it ran continuously across the pars prior

Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2016, at p. 134) similarly suggested that, in phase II:

“... the temples did not have fully closed alae [as in Phase I: instead, in Phase II], the alae were closed only along the length of the cellae, ... [as proved] by the fact that the ... slab pavement runs continuously across the N-S axis of the alae south of the southern limit of the cellae.”

He summarised the situation at p.209:

“The temples in this phase were tetrastyle prostyle with two rows of columns, and the front of their lateral alae no longer being closed.”

The dating of this pavement is clearly crucial for our understanding of the evolution of the site as a whole. Daniel Diffendale referenced below, 2017, at pp. 135-6) noted that an archeological report from 1975 recorded the discovery of a fragment of a Black Gloss bowl that dated to 320-290 BC,which probably (although not certainly) lay below the slab paving of the temple porches. He observed (at p. 138) that, if this were certainly correct:

“... then a date somewhere between [290-320 BC and 213 BC, the date of the fire that destroyed these temples, would be] indicated ...”

He added (at p. 134) that:

“Limited ceramic evidence excavated by the Sant’ Omobono Project [also ??] suggests a broad terminus post quem of the 4th century BC for this porch pavement, and it must predate the fire of 213 BC.”

Monuments on the Forecourt of the Temples

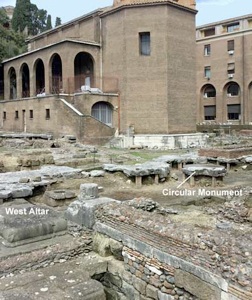

Excavated area at Sant‘ Omobono, showing the west altar and the circular monument

C-shaped altars (represented above by rectangles) and circular monument on the temple’s forecourt

From Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2017, at p. 118, Figure 32)

Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, 2016) discussed five monuments that stood on the temple forecourt:

✴two twin C-shaped altars (shown as rectangles in some of the plans above];

✴a circular [monument]; and

✴fragments from two bases carrying inscriptions of an ‘M. Folvios’.

I discuss these in turn below.

Altars

Images adapted from Stephen Smith (referenced below, at p. 293)

According to Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at p. 31):

“Two fragmentary altars still in situ on the Republican podium are probably ... connected with the [laying of the block] pavement[of the forecourt itself]. Unlike the temples (which face south) the altars face east. These are [C-shaped] in plan and would have originally been of the double-cushion variety with superimposed torus (Etruscan round) mouldings, although their upper cushions (crown mouldings) were removed in antiquity. The altar mouldings are carved in Lapis Albanus,

while their substructures are in one or more varieties of Tufo Lionato. The profile and plan of [these] ... altars find close comparanda in Altars XI and XII at Lavinium, dated stratigraphically

to the mid-4th century BC ... Immediately west of each altar are three rows of pavement slabs, aligned N–S with the Republican podium, which share the dimensions and manufacture of the Tufo Lionato porch pavement slabs but contrast with the blocks of the surrounding forecourt pavement. These slabs form a platform or platea analogous to those associated with the eponymous monuments in the sanctuary ... at Lavinium, probably related to the exigencies of the sacrificial ritual.”

Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2016, at p. 144) observed that:

“The two altars were the earliest of the five monuments [on the forecourt] to be discovered, during the [excavations] of 1937. The western altar was found bisected, possibly by the cutting for the sewer, ... [and the] missing central portion was filled in with concrete at some point soon after its excavation. The eastern altar was found with the southern two-thirds of its structure missing ... [Both] altars were found with the upper surface of their base-moulding blocks hacked down and, [as noted above], with] their crown mouldings removed.”

He pointed out (at pp. 145-6) that:

“Contrary to numerous statements and oft-reprinted plans, the altars are not precisely symmetrically-located on the Republican podium ...: the line of the northern edge of the plinth of the east altar lies 0.56 m north of the equivalent on the west altar ... [However]:

✴the interior western face of the west altar (between the wings) is aligned with the central axis of Temple A; [and]

✴if we assume that Temples A and B had symmetrical footprints within the [podium], then the interior western face of the east altar was also aligned with the centre line of Temple B.”

According to Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at p. 31):

Adjoining [and to the east of] each altar ... are the heads of pits or wells, sometimes (and not implausibly) termed ‘votive pits’, [one of which is visible in the photograph of the west altar above].

Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2016, at p. 152) observed that:

“While the head structure of the eastern pit is aligned with the [eastern C-shaped] altar and the Republican podium as a whole, the pit itself, [which is] rectangular in section, is aligned obliquely, sharing the orientation of the Archaic temple and altar ... [This pit also] communicates with the platform of the archaic altar, suggesting some kind of continuity of cult, ... [since] the common alignment of and communication between the eastern pit and the Archaic altar would hardly be possible if the former had not begun to be constructed while the latter was still visible.”

He pointed out (still at p. 152) that:

“If the altars are considered [to be contemporary] with their adjacent votive pits, ... this would suggest that they date to the initial construction of the Republican podium in the early 5th century BC. ... Even if the ... altars are not contemporary with the raising of [this podium], we must [assume that they] had predecessors that were [of this date, since] the altar was the fundamental element of central Italian sacred space, where altars may occur without temples, but not the reverse.”

In other words, it is possible that the two C-shaped altars that were discovered in situ on the temples’ forecourt had replaced two earlier altars that had been erected, together with the votive pits, in ca. 500 BC. In his subsequent thesis, Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2017, at p. 153) accepted that the C-shaped altars:

“... find close comparanda in Altars XI and XII at Lavinium, dated stratigraphically to the mid-4th century BC and (especially) in the [C-shaped] altar at Ardea (loc. Fosso dell’Incastro), ... [which] was initially dated generally to the 4th–3rd century BC ... based on the material employed and the comparison with Lavinium.”

He also observed (at pp. 154-5) that the altars at Sant; Omobono:

“... have generally been dated in tandem with the surrounding [forecourt] pavement ..., [which] cannot currently be dated more precisely than the 4th or 3rd century BC. [Furthermore, if we accept the [alternative] hypothesis that [they] are contemporary with the ... [earlier] slab porch pavement, they would date between the end of the 4th and the mid 3rd century BC ..., [which would be] in accord with the stylistic comparanda from Lavinium (mid-4th century BC) and Fosso dell’Incastro (first half 3rd century BC or earlier). It seems clear, then, that the existing altars are not contemporary with the initial phase of the Republican podium.”

Circular Monument

Image from Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2017, Fig. 57, at p. 157)

This monument was roughly equidistant from the two C-shaped altars, with the northern point in its circumference roughly aligned with the northern edge of the east altar (see the plan above). Daniel Diffendale (in the description that he attached to on an image of this monument that he published on Flickr) described it as:

“A stone base ... for the display of 2-3 ft. tall bronze statues.”

Since these statues would have almost certainly represented votive offerings, the monument is often characterised as a donarium. Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2016, at p. 153) described it as follows:

“Around a core of grey granular tufo, the monument is faced with both base and crown mouldings, each originally composed of seven blocks of lapis albanus; curiously, the monument was found with the southeastern block of each moulding missing, leaving only six blocks per course. ... This monument ... remains something of an unicum: while circular stone bases for the mounting of dedicated statues are common enough, the large, multi-piece circular design and decorative scheme are particularly curious.”

He observed (at p. 154) that:

“Parts of the underside of two blocks in the upper course of the ... circular monument have been cut away, leaving a hollow space beneath[that might be] reasonably .... [recognised] as a thesauros, since the ... blocks below show traces of bronze (for some sort of fitting?), and an illegible bronze coin was found in the interstices of the underlying blocks. This hollow lies in the southern side of the monument, perhaps facing visitors if they approached the temples from the south. Curiously, however, there is no aperture for the addition of coins ... , as one would expect for a thesauros: perhaps the hollow was intended to house a permanent votive cache.”

He also noted (at p. 158) that:

“It is likely that the monument would have been plastered and/or painted originally. ... [If so], the particular alignment of the blocks would not have been directly visible and their only effect would be on the positioning of the surmounted statues. In so far as it is possible to tell, each of the figures was contained within the bounds of a single block. In its surviving state, there is nothing particularly oriented about the circular monument, aside from the ‘thesauros’ [to the south] and the footprints of the statues.”

In his subsequent thesis, Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, at pp. 166-7) observed that:

“The comparanda adduced for ... [this] monument do not permit us to assign a secure stylistic date to it, nor to refine the broad 4th–3rd century date provided by the monument’s stratigraphic position. ... [However], the fine state of preservation of its details [suggests that it had] a short lifespan prior to its interment [after the fire of 213 BC - see below].”

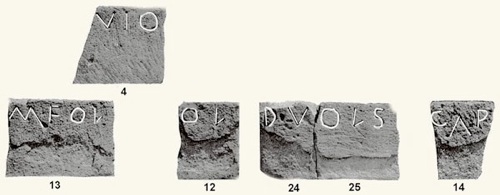

‘Folvios’ Monuments and Inscriptions

Remains of the circular monument and the ‘Folvius’ bases during the excavations of 1960

From Daniel Diffendale, referenced below, 2017, p. 158, Figure 59)

Inscribed fragments from Sant’ Omobono (from Daniel Diffendale, referenced below, 2016, Fig. 22, at p. 159)

Published as CIL VI 40895: M(arcos) Folṿ[io(s) Q(uinti) f(ilios), cos]ol [dede]d Volsi[niis] cap[tis]

M Fulvius, son of Quintus, consul, dedicated [it] after Volsinii had been captured

Mario Torelli (referenced below) proposed that they came from two identical inscriptions,

which he completed in this drawing

Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2016, at p. 159) observed that at least 26 fragments of worked lapis albanus were found with the dismantled blocks from the circular monument (see the photograph above), nine of which were distinguished by the facts that:

✴they were of similar dimensions and workmanship; and

✴they all had fittings on their top surfaces for the attachment of small bronze statues.

Furthermore, six of these nine blocks carried inscriptions (as illustrated above). He noted that Mario Torelli (referenced below) had separated the blocks into two distinct, though possibly identical, inscriptions and identified their dedicant as M. Fulvius Flaccus, who had the triumphed over Volsinii in 264 BC a reconstruction that has been widely accepted. Daniel Diffendale et al. (referenced below, at p. 32) summarised the likely scenario:

“Following his triumph over the Etruscan city of Volsinii in 264 BC, the consul M. Fulvius Flaccus seems to have made a dedication within the sanctuary of Fortuna and Mater Matuta, as attested by the fragmentary remains of at least two inscribed rectangular bases for small bronze statues. As these inscribed blocks were found dismantled within the destruction fill of 213 BC [ see below], their original position within the precinct cannot be determined.”

Daniel Diffendale (referenced below, 2017, at p. 28) observed that Torelli’s completion of the inscription(s) supports the notice of Pliny the Elder, to the effect that:

“... Metrodorus of Scepsis, who had his surname from his hatred of the [Romans], reproached us [i.e. the Romans] for having pillaged the city of Volsinii for the sake of the 2,000 statues that it contained”, (‘Natural History’, 34: 16).

The figure of 2,000 is likely to have been an exaggeration, but Flaccus must have taken a large number of cult statues to Rome (which almost certainly included a statue of Vortumnus for the temple that he built on the Aventine - see below). However, as Diffendale observed (still at p. 28):

“... only a dozen of these could[have been] accommodated on each of the two inscribed bases [that were probably formed by the recovered blocks].”

Temples of Mater Matuta and Fortuna in History

M. Furius Camillus and the Fall of Veii (396 BC)

We should now look in more detail at some aspects of Livy’s account Camillus’ first dictatorship of 396 BC, when he was given command against Veii:

“[When] everything was in readiness for the campaign, Camillus vowed, in pursuance of a senatorial decree:

✴to celebrate the great games if he should capture Veii; and

✴Matutae Matris refectam dedicaturum (to restore and re-dedicate) the temple of Mater Matuta, which had previously been dedicated by King Servius Tullius”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 19: 6).

After he had succeeded in capturing and destroying Veii, he returned to Rome and celebrated a triumph in which:

“...he rode into the City on a chariot drawn by white horses ... [and] then:

✴let the contract for the temple of Juno Regina on the Aventine; and

✴dedicated a temple to Mater Matuta.

Having fulfilled these obligations to gods and men, laid down the dictatorship”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 23: 7).

This suggests that the temple of Mater Matuta had been ‘restored’ during Camillus absence, and that Camillus’ role in both:

✴the vowing of this work (which, in Livy’s account, was explicitly at the behest of the Senate); and

✴the subsequent rededication (together with the letting of the contract for the temple of Juno Regina);

had been purely honorific. However, it raises the question of why the Senate had decided to ‘restore’ the temple of Mater Matuta (but not the twin temple of Fortuna) as Camillus had left for Veii.

Perhaps this decision had something to do with the Senate’s plans for Juno Regina, the patroness of Veii, should Camillus’s campaign succeed. According to Livy, at, at the start of Camillus’ final assault on Veii:

“... after taking the auspices, ... [Camillus proclaimed]:

‘Under your leadership, Pythian Apollo, and inspired by your divine will, I go forth to destroy the city of Veii. To you I vow a tenth part of its spoils’.

At the same time, [he addressed Juno Regina]:

‘You who now dwell in Veii, I pray that you follow us in our victory into the city that is ours and will soon be yours, where a temple worthy of your greatness will receive you’”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 21: 2).

As Valerie Warrior (referenced below, at p. 359, note 41 observed, in this prayer:

“... Camillus performs the ritual of evocatio, the summoning of an enemy’s tutelary deity to desert the city and its inhabitants, come over to the Romans, and accept a new home in Rome.”

After the Romans had captured Veii and seized:

“... the wealth that belonged to men, ... they began to remove the gods’ gifts and the gods themselves, but did so more in the manner of worshipers than plunderers. Young men were chosen from the whole army and were assigned the task of bringing Juno Regina to Rome. ... [We] hear that she was moved from her place almost effortlessly with poles [that were presumably normally used in processions], ... and that she was light and easy to transport. She was carried, undamaged, to the Aventine, her eternal home, where the prayers of Camillus had summoned her, and where he later dedicated the temple that he had vowed”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 22: 3-7).

Livy seems to suggest here that Camillus’ prayers to both Pythian Apollo and Juno Regina had been made on his own initiative, but that could be a later elaboration. I wonder whether the decision to bring the cult statue of Juno Regina to Rome had been taken before Camillus left for Veii, and whether this was the reason for the decision to ‘rebuild and re-dedicate’ the temple of Mater Matuta. After all, according to Livy;

Livy records that the cult statue of Juno Regina was ‘carried’ to the Aventine before Camillus had let the contract for her temple, which he would subsequently dedicate, but he does not record where she ‘resided’ during the temple’s construction. It seems to me that she would have been brought to Rome by river, and that the temple of Mater Matuta in the Forum Boarium, at the foot of the Aventine, would have been an obvious place in which she could be temporarily housed.

In other words, we cannot rule out the possibility that:

Camillus did indeed make some modifications to this temple (but not to its twin) in 396 BC in order to make it a fit place for Juno’s temporary residence; and

this was accompanied by some kind of re-dedication.

However, the earliest surviving reference to the physical presence of temples of both Mater Matuta and Fortuna in the Forum Boarium relates to the events of 213 BC, when, according to Livy, Rome witnessed the outbreak of :

“... a dreadful fire ... that continued for two nights and a day: everything was burnt to the ground between the Salinae and the Porta Carmentalis, including the Aequimaelium, the Vicus Jugarius and the temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 47: 15).

(I discuss the evolution of the site after this fire in the closing section below).

According to Livy, in 213 BC, Rome witnessed the outbreak of :

“... a dreadful fire ... that continued for two nights and a day: every thing was burnt to the ground between the Salinae and the Porta Carmentalis, including the Aequimaelium, the Vicus Jugarius and the temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 47: 15).

Then, in 212 BC:

“Five commissioners were chosen to undertake the repair of the walls and towers of the City, and two boards, each consisting of three members, were selected;

✴one to inspect the contents of the temples and to make an inventory of the offerings; [and]

✴the other to rebuild:

•the temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta inside the Porta Carmentalis; and

•the temple of Spes outside, all of which had been destroyed by fire in the previous year”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 7: 5-6).

[This is supported by archaeological evidence (Diffendale et al., 2016: 34-7).]

According to Livy, in 196 BC:

“L. Stertinius, returning from Farther Spain, without even putting in a claim to a triumph, deposited 50,000 pounds of silver in the treasury and, out of the booty:

✴erected:

•two arches in the Forum Boarium in front of the temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta; and

•one in the Circus Maximus; and

✴placed gilded statues on these arches”, (‘History of Rome’, 33: 27: 3-4).

According to Livy, in 174 BC:

“... a tabula was set up in the temple of Mater Matuta with the following inscription:

‘Under the command and auspices of Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus ,the legion and army of the Roman people conquered Sardinia. In this province, more than 80,000 enemy soldiers were killed or captured. Having been most successfully administered the State, liberated the allies and restored the revenues, [Sempromnius] returned to Rome with his army safe and and enriched with booty. He entered Rome in triumph for the second time. In commemoration of this event he set up this tabula to Jupiter.’

[The tabula] had the form of the island of Sardinia, and on it representations of battles were painted”, (‘History of Rome’, 41: 28: 8-10).

Read more:

Brock A. L., Motta L. and Terrenato N, “On the Banks of the Tiber: Opportunity and Transformation in Early Rome”, Journal of Roman Studies, 111 (2021) 1-30

Terrenato N., “The Early Roman Expansion into Italy: Elite Negotiation and Family Agendas”, (2019) Cambridge and New York

Bernard S., “Building Mid-Republican Rome: Labor, Architecture, and the Urban Economy”, (2018) Oxford and New York

Winter N., “Acroteria in Etruria and Central Italy, 640/630-500 BC”, in:

Moustaka A. (editor), “Terracotta. Sculpture and Roofs: New Discoveries and New Perspectives”, (2018) Athens, at pp. 195-207

Brocato P. and Terrenato N., “The Archaic Temple of S. Omobono: New Discoveries and Old Problems”, in:

Lulof P. S. and Smith C. (editors), “The Age of Tarquinius Superbus: Central Italy in the Late 6th Century”, (2017) Leuven, Paris and Bristol CT, at pp. 97–106

Davies P., “Architecture Politics in Republican Rome”, (2017) Cambridge

Mura Sommella A, “Arianna Ritrovati: Un Nuove Grppo Acroteriale dall’ Area Sacra del Foro Boario”, in:

Lulof P. S. and Smith C. (editors), “The Age of Tarquinius Superbus: Central Italy in the Late 6th Century”, (2017) Leuven, Paris and Bristol CT, at pp. 107-12

Diffendale D. P., “The Roman Middle Republic at Sant’ Omobono”, (2017) thesis of the

University of Michigan

Diffendale D. P., “Five Republican Monuments: On the Supposed Building Program of M.

Fulvius Flaccus”, in:

Brocato P., Ceci M. and Terrenato N. (editors), “Ricerche nell' Area dei Templi di Fortuna e Mater Matuta, Vol. I.”, (2016) Università della Calabria, at pp. 141–66

Diffendale D.P., Brocato P., Terrenato N. and Brock A. L., “Sant' Omobono: an Interim Status Quaestionis”, Journal of Roman Archaeology, 29 (2016) 7–42

Terrenato N., “Temples of Sant’Omobono”, Oxford Classical Dictionary (2016), online

Smith S., “Sacred by Design: Expressing Latin Identity through Architectural Mouldings”, (2015) thesis from Royal Holloway, University of London

Hopkins J. N., “Genesis of Roman Architecture’, (2006) New Haven CT and London

Warrior V. M., “Livy: History of Rome, Books 1–5 (Translated, with Introduction and Notes)”, (2006) Indianapolis IN

Bonfante G. and Bonfante L., “The Etruscan Language: An Introduction (Revised Edition)”, (2003) Manchester

Mura Sommella A., “‘La Grande Roma dei Tarquini’: Alterne Vicende di una Felice Intuizione,” Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, 101 (2000) 7-26

Coarelli F., “Il Foro Boario: Dalle Origini alla Fine della Repubblica”, (1988)Rome

Oleson, J. P., "Greek Myth and Etruscan Imagery in the Tomb of the Bulls at Tarquinia", American Journal of Archaeology, 79:3 (1977) 189–200

Torelli M., “Il Donario di M. Fulvio Flacco nell' Area di Sant’ Omobono”, Quaderni dell'Istituto di Topografia Antica della Università di Roma, 5 (1968 ) 71-6

Kent R. G. (translator), “Varro: On the Latin Language, Vol. I: Books 5-7”, (1938) Cambridge MA

Frazer J. G. (translator), “Ovid: Fasti”, (1931) Cambridge MA

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)