Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temples of Venus Erycina and Mens

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Temples of Venus Erycina and Mens

Foundation of the Temples

These two temples were founded in the wake of the Romans’ disastrous defeat by Hannibal at Lake Trasimene in 217 BC, when Q. Fabius Maximus Verrucosus was appointed as dictator. According to Livy, on his first day as dictator, he convinced the Senate that the consul C. Flaminius, who had been killed during the battle:

“... had erred more through his neglect of the ceremonies and the auspices than through his recklessness and ignorance. [Verrucosus therefore] insisted that they ... do what is rarely done (except when dreadful prodigies have been announced) and order the decemviri to consult the Sibylline books. ... the decemviri, [having performed this task], reported to the Senate that:

✴the vow that had been made to Mars on account of this war, which had not been duly performed, must be performed again on a larger scale;

✴great games must be vowed to Jupiter;

✴temples to Venus Erycina and to Mens must be vowed ...

Since Verrucosus would be occupied with the conduct of the war, the Senate commanded the praetor M. Aemilius ... to see that all these measures were promptly put into effect”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 9: 7-11).

All of these measures were quickly taken: of relevance here is the fact that:

“The temples were then vowed:

✴that to Venus Erycina by [Verrucosus] because the [Sibylline Books] had given out that he whose authority in the state was paramount should make the vow; and

✴that to Mens by the praetor, T. Otacilius Crassus”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 10: 10).

As Andrew Erskine (referenced below, at p. 201):

“... the ‘conjunction of the Temple of Venus with that of Mens, the personification of good sense, signalled that, under [Verrucosus], wise counsel would replace the recklessness of Flaminius, the commander at Trasimene,”

The temples were both built within two years: Livy recorded that:

“Towards the close of [215 BC, Verrucosus] asked the Senate to allow him to dedicate the temple of Venus Erycina, which he had vowed when dictator. The Senate passed a decree that T. Sempronius, the consul-elect, immediately upon his entering office, should propose a resolution to the people that [Verrucosus] be one of the duoviri aedi dedicandae (two men appointed to dedicate the temples)”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 30: 13-14).

Soon after:

“... duoviri aedi dedicandae were appointed:

✴T. Otacilius Crassus dedicated the temple of Mens; and

✴[Verrucosus] dedicated the temple of Venus Erycina.

Both are on the Capitol, separated only by a water channel”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 31: 9).

Ovid (see below) recorded the dies natalis of the Temple of Venus Erycina on 23rd April and that of the Temple of Mens as 8th June: this date was also recoded for

✴Venus Erycina, in the fasti Antiates Maiores; and

✴Mens: as Menti in Capitolo in the fasti Venusini.

Cult of Venus Erycina

Aeneas and the Cult of Venus in Sicily and Latium

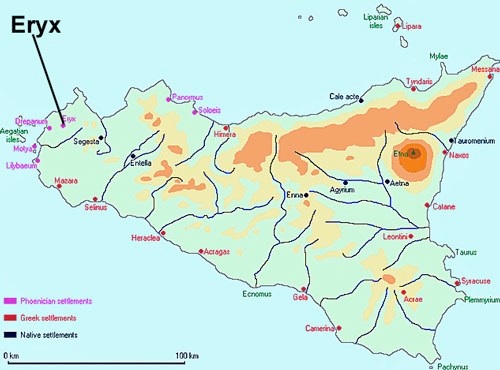

Map of Ancient Sicily

According to Solinus (4th century AD), in Roman tradition, Aeneas had brought the cult of his mother, Aphrodite (Roman Venus) from Sicily to Latium:

✴Solinus cited L. Cassius Hemina (1st half of the 2nd century BC) for the information that:

“... in the 2nd summer after the capture of Troy, Aeneas landed on the shores of Italy with not more than 600 companions and pitched camp in the territory of Lavinium”, (‘Wonders of the World’, 2: 14, translated by Timothy Cornell, in T. C. Cornell (editor), referenced below, Vol. II, at p. 253); and

✴he might well have relied on Hemina for some or all of the rest of his short account of Aeneas’ sojourn in Italy:

“While he was dedicating a statue to his mother, Venus (who is called Frutis), which he had brought from Sicily, he [received the statue of Pallas Athena that was known as] the Palladium from Diomedes, [an Achean commander who had stolen it from Troy].

•He soon began a 3-year period of joint rule [over Latium with the incumbent king], Latinus, from whom he received 500 iugera of land; and

•after the death of Latinus, he held supreme power for 2 years.

In the 7th year [from the fall of Troy], he disappeared at the River Numicius, [after which], he was given the name ‘father Indiges’”, (‘Wonders of the World’, 2: 14-5, translated by Timothy Cornell, in T. C. Cornell (editor), referenced below, Vol. II, at p. 253).

Timothy Cornell, (in T. C. Cornell (editor), referenced below, Vol. III, at p. 165) pointed out that:

“The statue [of his mother that had brought from Sicily] is that of Venus Erycina.”

In this context, Cornell cited Servius (4th century AD) in his commentary on Virgil’s ‘Aeneid’: in a list of epithets given to Venus, Servius recorded that:

“Est et Erycina, quam Aeneas secum aduexit”, (’ad Aen’, 1: 720).

“She is also Erycina, whom Aeneas brought with him with him [from Mount Eryx in Sicily]”,(my translation).

Festus (2nd century AD), in his epitome of the lexicon of the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus, also referred to the Roman tradition in which Aeneas had brought the cult of Venus to Latium:

“... ... when [Aeneas] was sacrificing to his mother, Venus, in litore Laurentis agri (on the shore of Lavinium) ... he veiled his head ...”, ('De verborum significatu', 432L, my translation: see Stephen Oakley, referenced below, 1998, at p. 506 for the fact that the people of Lavinium were known as the Laurentes).

As Fay Glinister (referenced below, at p. 198, note 23) pointed out, this passage should probably be read alongside the following passage by Strabo (late 1st century BC/ early 1st century AD):

“Midway between [Ostia and Antium] is Lavinium, which has a sanctuary of Aphrodite that is common to all the Latins, although the the [people of Ardea], through attendants, take care of it. Then, there is Laurentium [and] Ardea .... There is an Aphrodision [near Ardea] where the Latins hold festivals. The Samnites destroyed these places, and only traces of the cities are left, honoured:

✴because Aeneas visited them; and

✴for the sacred rites that they say have been handed down from those times”, (‘Geography’, 5: 3: 5, translated by Duane Roller, referenced below, at p. 236).

Pliny the Elder (‘Natural History’, 3: 9: 4, 1st century AD) referred to a settlement near Ardea called Aphrodisium. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 285) argued that the Samnites march towards Rome after their victory at Lautulae in 315 BC provides the obvious context for this notice.

The Romans’ interest in the cult of the goddess seems to have taken place in the First Punic War (264 -241 BC), beginning in 249 BC, when the consul L. Junius Pullus took refuge on the mountain after he had lost most of his fleet in a storm. According to Polybius (ca. 150 BC) :

“Junius, returning to the army after the shipwreck in a state of great affliction, ... [was] most anxious to make good the loss inflicted by the disaster. Therefore, as soon as a slight opportunity arose, he surprised [the Carthaginians] and occupied Eryx, taking possession of both of the temple of Aphrodite [Roman Venus] there and of the town. Eryx is a mountain on the sea , ... situated between Drepana and Panormus ... . On its summit, which is flat, stands the temple of Aphrodite of Eryx, which is indisputably the first in wealth and general magnificence of all the Sicilian holy places. The city extends along the hill under the actual summit, the ascent to it being very long and steep on all sides. [Junius] garrisoned the summit and also the approach from Drepana, and jealously guarded both these positions, especially the latter, in the conviction that, by this means, he would securely hold the city and the whole mountain”, (‘Histories’, 1: 55: 5-9).

Polybius noted that, at this point, the Romans had given up hope of victory at sea and Eryx was to be their base of operations against the Carthaginians for the next five years, at which point, the tide of war finally turned in their favour. Andrew Erskine (referenced below, at p. 203) pointed out that this experience is sufficient to explain why the Romans established the cult of Venus Erycina on the Capitol in 217 BC, at a particularly low moment in their second encounter with the Carthaginians.

At some point thereafter, the Romans began to associate Aeneas with the Sicilian cult. The earliest evidence for this comes from Diodorus Siculus (1st century BC), who recorded that:

“[When] Aeneas, the son of Aphrodite, ... was on his way [from Troy] to Italy and came to anchor off [Sicily, he] embellished the [ancient] sanctuary [at Eryx] with both magnificent sacrifices and votive offerings, since it was that of his own mother. After him the [indigenous] Sicanians paid honour to the goddess for many generations and kept continually embellishing [her shrine]; and thereafter, the Carthaginians, when they had become the masters of parts of Sicily, never failed to hold the goddess, [whom they called Astarte], in special honour. Finally, when the Romans had subdued all Sicily, they surpassed all the people who had preceded them in the honours that they paid to her, ... since they traced back their ancestry to her. For this reason, they were successful in their undertakings and [readily honoured the goddess] who was the cause of their rise to power ... For example, the consuls and praetors who visit the island and all Romans who sojourn in positions of any authority, whenever they come to Eryx, embellish the sanctuary with magnificent sacrifices and honours and, laying aside the austerity of their authority, enter into sports and have conversation with women in a spirit of great gaiety, believing that only in this way will they make their presence there pleasing to the goddess. Indeed, the Roman Senate has so zealously concerned itself with the honours of the goddess that it has decreed that the 17 cities of Sicily that are most faithful to Rome shall pay a tax in gold to Aphrodite, and that 200 soldiers shall serve as a guard of her shrine”, (‘Library of History’, 4: 83: 4-7).

In construction from this point

Roman Cult of Venus Erycina

Ovid (early 1st century AD) referred to this goddess in his account of the Vinalia on 23rd April:

“I will now tell of the festival of the Vinalia ... [when] common girls celebrate the divinity of Venus, who favours the earnings of ladies of a liberal profession. ... Now is the time to throng her temple next the Colline gate see below]; the temple takes its name from the Sicilian hill [of Eryx]. When [M. Claudius Marcellus] carried Arethusian Syracuse by force of arms and also captured Eryx, Venus was transferred to Rome in obedience to an oracle of the long-lived Sibyl, and chose to be worshipped in the city of her own offspring”, (‘Fasti’, 4: 863-876, translated by James Frazer, referenced below, at p. 253).

Ovid referred here to two cult sites in Rome:

✴the temple of Venus Erycina on the Capitol (above), which he mistakenly associates with M. Claudius Marcellus, who captured Syracuse in 211 BC (see Andrew Erskine, referenced below, at pp.199-200 and note 6); and

✴the later temple of Venus Erycina outside Porta Collina (discussed below).

This suggests that these temples shared the dies natalis of 23rd April, which coincided with the annual wine festival known as the Vinalia Priora.

Cult of Mens

Read more:

Roller D. W., “The Geography of Strabo: An English Translation, with Introduction and Notes”, (2014) Cambridge

Cornell T. C., “The Fragments of Roman History”, (2013) Oxford

Glinister F., “Veiled and Unveiled: Uncovering Roman Influence in Hellenistic Italy”, in:

Gleba M. and Becker H. (editors), “Votives, Places and Rituals in Etruscan Religion”, (2008), at pp. 193–215

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Vol. III: Book IX”, (2005) Oxford

Erskine A., “Troy Between Greece and Rome: Local Tradition and Imperial Power”, (2001) Oxford and New York

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume IV: Book s VII and VIII”, (1998) Oxford

Frazer J. G. (translator), “Ovid: Fasti”, (1931) Cambridge MA

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)