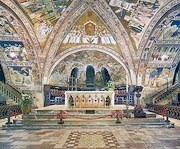

The redecoration of the apse and the vaults over the high altar of the Lower Church belonged to Phase II of the redecoration (as defined in the page on San Francesco in the 14th Century), which was probably also carried out in ca. 1305-11, which also involved:

-

✴most of the right transept; and

-

✴the Cappella di Santa Maria Maddalena.

These frescoes are also reasonably securely attributed to Giotto and his workshop, and form part of an iconographical programme for the redecoration of what had been the friars’ choir that was probably decided upon during the General Chapter meeting at Assisi in 1304. It seems likely that the work was financed by the loan that Palmerino di Guido repaid in Assisi in 1309 on his own behalf and that of “Giotto Bondoni of Florence”.

The work seems apparently ended abruptly:

-

✴fragments of the earlier decoration survive on the lower part of the ribs of the crossing; and

-

✴the lower part of the fresco on the wall of the apse was never completed. (This work was subsequently over-painted).

Elvio Lunghi (reference [a] below) has suggested that the work was probably terminated at the time of the documented flooding of the lower church in 1311.

Fresco in the Apse

The original incomplete fresco on the wall of the apse was later replaced, and is therefore known only from documents.

-

✴Lorenzo Ghiberti referred to it in ca. 1450, with an attribution to Stefano Fiorentino. He described its subject as “una gloria”, and commented on its high quality, albeit that it was unfinished.

-

✴Giorgio Vasari, in the 2nd edition (ca. 1568) of his “Lives of the Artists, gave the work the title by which it is still known: “Gloria Celeste” (the glory of Heaven). He followed Ghiberti (and a number of other early authorities) in attributing it to Stefano Fiorentino and in commenting on its high quality.

-

✴Fra. Ludovico da Pietralunga (referenced below), who provided the most detailed description of the fresco, attributed it to Puccio Capanna.

If Fra. Ludovico’s attribution were correct, this would be the earliest of Puccio’s works as an independent artist. However, most scholars follow Ghiberti and Vasari in attributing it to Stefano Fiorentino.

The lost fresco seems to have represented an allegory of the stigmatisation of St Francis. The decision to celebrate of the stigmatisation in the most sacred space in San Francesco was probably associated with a general intensification of interest in it in ca. 1305:

-

✴At the Franciscans’ request, Pope Benedict XI approved the Feast of the Stigmatisation of St Francis (17th September) as a proper feast for the Order in 1304.

-

✴Brother Ubertino da Casale (the leading Spiritual Franciscan -see below) included a long exposition of the apocalyptic significance of the stigmatisation of St Francis in his “Arbor Vitae Crucifixae Jesu Christi” (1305) which he wrote during a stay at the convent on Mount La Verna, the place where the stigmatisation had occurred. (This work is translated in part by R. Armstrong et al. - referenced below).

-

✴Cardinal Napoleone Orsini, who appointed Ubertino as his chaplain and who was closely associated with the decoration of the lower church (see below), granted an indulgence for those visiting the convent on Mount La Verna or supporting the poor friars there in 1306.

According to Fra Ludovico da Pietralunga , the upper part of the composition in the apse involved:

-

✴a crucifix with two wings below an astrolabe, at the apex;

-

✴two angels to each side of the crucifix, holding (respectively) a mirror, a throne, a church and a cloth or veil; and

-

✴two angels below the crucifix, holding what seems to have been a representation of the Seventh Seal, the opening of which signalled the end of the world.

At the centre of the composition, immediately below the crucifix, was a figure of St Francis, with his arms outstretched. Fra Ludovico does not mention his stigmata, which suggests that they were not unusually prominent. Nevertheless, the pose itself must have signified the affinity between St Francis and the crucified Christ.

Standing figures of St Francis with his arms outstretched were not particularly uncommon: he is, for example, depicted in this way in two of the earlier frescoes in the upper church:

-

✴In Scene XII, he is depicted as his brothers saw him while he prayed “with his hands outstretched in the form of a cross, his whole body lifted up from the ground and surrounded by a sort of shining cloud” (“

Legenda Maior” 10:4, also recorded in the “

Vita Secunda” 95).

-

✴In Scene XVIII, he is depicted as Brother Monaldo saw him in a vision that occurred as he listened to a sermon by St Antony of Padua at the Chapter at Arles. During the vision, St Francis appeared “lifted up in the air with his hands extended as if on a cross” (“

Legenda Maior” 4:10, also recorded in the “

Vita Prima” 48). St Antony had been preaching on the theme of “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews”, the inscription that adorned the cross on which Jesus was crucified: its Latin acronym, “INRI”, appeared in the astrolabe at the apex of the apse fresco (see below).

However, in the representation in the apse of the lower church, St Francis apparently protected under his cloak a circle of about 40 male and female followers, (although only their heads, at the level of the cord around his waist, were completed). This iconography of the stigmatised St Francis as an intercessor is unusual in art. It is more common in hagiography: for example, it is articulated in the “Vita Prima”, in which St Francis is beseeched to show the stigmata to Christ so that He “may mercifully bare His own wounds to the Father and, because of this, the Father will ever show us in our anguish His tenderness” (paragraph 119). This depiction of the protective St Francis under a representation of the Seventh Seal suggests that St Francis was depicted here specifically as an intercessor for the righteous at the Final Judgement.

It is not clear how this composition accommodated the windows in the apse. It seems likely that the figure of St Francis was slightly lower than the figure of Christ that now stands above the central window.

Frescoes in the Vaults

These frescos are the autograph works of an anonymous follower of Giotto known as the Maestro delle Vele. Their highly complex iconography was, as far as we know, unprecedented.

The iconography of these frescoes is of an emphatically apocalyptic nature, as would be expected since they are sited directly above the tomb of St Francis. This characteristic is announced by the image in the keystone, which probably represents a vision of Christ from Revelations 1: 14-18: “His head and hair were white like wool, as white as snow, and his eyes were like blazing fire. His feet were like bronze glowing in a furnace, and his voice was like the sound of rushing waters. In his right hand he held seven stars, and out of his mouth came a sharp double-edged sword. His face was like the sun shining in all its brilliance. When I saw him, I fell at his feet as though dead. Then he placed his right hand on me and said: ‘Do not be afraid. I am the First and the Last. I am the Living One; I was dead, and behold I am alive for ever and ever! And I hold the keys of death and Hades’.”

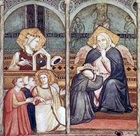

This apocalyptic character is reinforced by the images of symbols of the Apocalypse on the ribs of the vaults, which include, for example, the four horsemen (illustrated here).

The other scenes depict (clockwise from the vault nearest the right transept):

-

✴allegories of the three fundamental aspects of the Franciscan Rule:

-

•an allegory of Chastity, which is related to the iconography of the Annunciation and the early life of Christ in the adjacent right transept;

-

•an allegory of Poverty that features

the marriage of St Francis and “Lady Poverty”, which would presumably have been reflected in the iconography used in the nave if it had ever been redecorated; and

-

•an allegory of Obedience, which is related to the iconography of the Passion of Christ in the adjacent left transept; and

-

✴St. Francis in glory, which was related to the allegory of his stigmatisation in the original fresco of the apse (described above).

Each scene is described by a Latin verse inscribed on the arch below it. The inscription related to the image of St Francis in glory expresses the overall message of the cycle: St Francis had revived the original form of evangelical life in the Franciscan Rule, which comprises the holy trinity of poverty, obedience and chastity and leads to salvation:

...ATOR RENOVAT/ IAM NORMAM EVANGELICAM

FRANCISCUS CUNCTIS PREPARAT/ VIAM SALUTIS CELICAM

PAUPERTATEM DUM REPARAT/ CASTITATEM ANGELICAM

OBEDIENDO COMPARAT / TRINITATEM DEIFICAM

ORNATUS HIS VIRTUTIBUS/ ASCENDIT REGNATURUS

HIIS CUMULATUS FRUCTIBUS/ PROCEDIT IAM SECURUS

CUM ANGELORUM CETIBUS/ ET CHRISTO PROFECTURUS

FORMAM QUAM TRADIT FRATRIBUS/ SIT QUISQUE SECUTURUS

In all of the frescos, St Francis appears barefoot, stigmatised, and unbearded:

-

✴the absence of shoes signals his obedience to the admonition of Christ to the Apostles as, for example, in Matthew 10:9: "Take no gold, nor silver, nor copper in your belts, no bag for your journey, nor two tunics, nor sandals, nor a staff”, which was the basis of the original form of evangelical life and of the Franciscan Rule;

-

✴the emphatic presence of the stigmata in the context of allegories of the Franciscan Rule reflects, for example, the relevant passage in the “Legenda Maior”: after describing how St Francis had received the Rule from God and how Pope Honorius III had confirmed it, St Bonaventure added: “To confirm this with greater certainty by God’s own testimony ... the stigmata of our Lord Jesus were imprinted upon [St Francis] by the finger of the living God, as the seal of ... Christ” (4:11); and

-

✴the iconography of the unbearded St Francis suggests that he is portrayed here after having defeated death (as in the iconography of “Sol invictus”, the unconquered sun, an allegory of the resurrected Christ) by following the Franciscan Rule.

Before looking at these vault frescoes individually, it is interesting to consider other, nearby frescoes that seem to form part of the same iconographical programme.

Other Related Frescoes

The four frescoes on the back wall of the transepts (i.e. the right wall of the left transept and the left wall of the right transept) should probably be read in relation to the frescoes in the apse and crossing vaults. Those in the right transept belong similarly to Phase II: those in the left transept were painted subsequently, but seem (as noted above) to have been conceived as part of the same iconographical programme.

Stigmatisation of St Francis

This fresco, immediately to the left of the crossing, clearly relates to the allegory of the stigmatisation in the apse. It was probably also intended to represent the divine seal of approval on the aspects of the Franciscan Rule depicted in the crossing vaults. A similar juxtaposition was used for the frescoes (ca. 1320) of the

Bardi Chapel of Santa Croce, Florence, where the stigmatisation of St Francis is portrayed above the entrance to the chapel and allegories of the Franciscan Rule appear in the vaults.

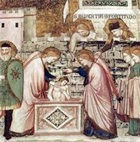

Revival of a Dead Child

The fresco in the right transept that forms the pendant to the stigmatisation depicts a posthumous miracle in which St Francis revived a boy who had fallen to his death. St Bonaventure described this miracle in his appendix to the “

Legenda Maior” on the Miracles of St Francis (2:4), following the account in the “

Tractatus de Miraculis” 2:42.

This miracle occurred when some passing friars interceded with St Francis, but only after the dead boy’s father had affirmed his faith that St Francis could revive his son “because of the love that he always had for Christ, who was crucified to give life back to all”. This expression of faith is at the heart of the composition. This underlines the new promise of salvation attendant upon the stigmatisation of St Francis: "Conformed to the death of Christ Jesus by sharing his suffering … [St Francis] gladdens the whole world with the gift of new joy, and offers to all the benefits of true salvation” (“Vita Prima”, paragraph 119).

Death of Judas and the Triumph of St Francis over Death

The fresco to the left of the stigmatisation depicts the suicide (by hanging and evisceration) of Judas. Janet Robson (referenced below) points out that Judas represented:

-

✴avarice, the opposite of Franciscan poverty; and

-

✴despair, the negation of any hope in the possibility, through repentance, of salvation.

The fresco in the right transept that forms the pendant to the death of Judas depicts St Francis holding what seems to be a portrait of a crowned skeleton, presumably his own. A link between this second fresco and those in the vaults is provided by the fact that St Francis is once more barefoot, stigmatised and unbearded.

Janet Robson has pointed up the stark contrast between these two frescoes:

-

✴the fresco of the death of Judas “epitomises the ignominious end of a man who has fallen into despair and whose punishment is death and eternal damnation”; while

-

✴the triumph of St Francis offers salvation to all those who repent in the hope of salvation.

Allegories of the Franciscan Rule

Allegory of Obedience

In the allegory of Obedience, the personification of the virtue is represented by a cloaked angel who has a square nimbus. He sits in front of a frescoed crucifix, and enjoins silence (by placing a finger to his lips) as he places a yoke on the shoulders of a kneeling friar.

-

✴To the left, an angel welcomes a young nobleman, while a tonsured figure in a red cassock looks on. A double-faced personification of Prudence, who has a polygonal nimbus, appears above them.

-

✴To the right, another angel expels a centaur (representing disobedience). A personification of Humility, who also has a polygonal nimbus, appears above them.

The scene is set in a Chapter House, with kneeling saints and angels to the sides. St Francis, who also wears a yoke across this shoulders, stands on the roof of the Chapter House while two hands above him hold what could be a crown.

The inscribed verse that relates to this scene reads:

VIRTUS OBEDIENTIE / IUGO CHRISTI PERFICITUR

CUIUS IUGO DECENTIE / OBEDIENS EFFICITUR

ASPECTUM HUNC MORTIFICAT / SET VIVENTIS SUNT OPERA

LINGUAM SILENS CLARIFICAT / CORDE SCRUTATUR OPERA

COMITATUR PRUDENTIA / FUTURAQUE PROSPICERE

SCIT SIMUL AC PRESENTIA / IN RETRO IAM DEFICERE

QUASI PER SEXTI CIRCULUM / AGENDA CUNCTA REGULAT

ET PER VIRTUTIS SPECULUM / OBEDIENTIE FRENULAT

SE DEFLECTIT HUMILITAS / PRESUMPTIONIS NESCIA

CUIUS IN MANU CLARITAS / VIRTUTUM SISTIS CON[SCIA]

Allegory of Chastity

In the allegory of Chastity, the personification of the virtue (identified as St Castitas) is represented by a veiled lady with a polygonal nimbus, who prays in the crenellated tower of a castle, as angels present her with a crown (from the left) and a palm.

-

✴To the left, St Francis welcomes a friar, a Poor Clare and a continent spouse.

-

✴At the centre, in front of the guarded castle, a pair of angels baptise a young man under the gaze of SS Munditia (cleanliness) and Fortitudo (fortitude), each of whom has a polygonal nimbus. The iconography here seems to equate baptism with bodily resurrection, and this is apparently the necessary precursor for entry into the castle.

-

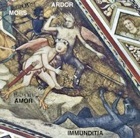

✴To the right, three crowned figures and an angel in a Franciscan habit (identified as Penitentia or Penitence) expel four personifications:

-

•Mors, a black demon with the legs of a spider who personifies death;

-

•Amor, a winged and blindfolded naked figure with clawed feet, wearing a crown of roses and a sash of human hearts, who personifies carnal love;

-

•Ardor, another winged figure, this time half man and half beast, with its hair on fire, who personifies ardour and desire; and

-

•Immunditia, a black boar, who personifies filth (in opposition to St Munditia above).

The inscribed verse that relates to this scene reads:

CASTITATIS ORANTI / PRO VICTORIA CORONE

DATUR CAPITAL ...

AD HANC QUERENS ACTINGERE/ HONESTATE SE TEGAT

LOCO DATUR PERTINGERE / SI FORTITUDO PROTEGAT

DUM CASTITAS PROTEGITUR / PER VIRTUOSA MUNERA

NAM CONTRA HOSTES TEGITUR / PER PASSI CHRISTI VULNERA

DEFENDIT PENITENTIA / CASTIGANDO SE CREBRIUS

MORTIS REMINISCENTIA / DUM MENTEM PULSAT SEPIUS

FRATRES SORORES ADVOCAT / ET CONTINENTES CONIUGES

CUNCTOS AD EAM PROVOCAT / FRANCISCUS ....

Allegory of Poverty

In this fresco, Christ officiates at the marriage of St Francis and Lady Poverty, under the gaze of Hope and Charity to the right. The bride, who is dressed in rags but adorned with wings and a polygonal nimbus, stands amid brambles in front of a rose bush and a lily. A small dog barks her and two small boys threaten to attack her: one is about to throw a stone and the other brandishes a stick.

-

✴Above, two angels fly up to Heaven, where a crowned figure (perhaps a friar) awaits them. One of the angels carries a purse and a red cloth; and the other carries a palace (with an adjacent walled garden).

-

✴To the left, an angel welcomes a young man who is giving his cloak to a pauper.

-

✴To the right, another angel and a friar try to persuade two rich men to join the community. One of the men holds a bird of prey on his glove and the other, who is tonsured, holds what seems to be a bag of money.

The inscribed verse that relates to this scene reads:

[PAUPERTAS] SIC CONTEPNITUR / DUM SPERNIT MUNDI GAUDIA

VESTE VILI CONTEGITUR / QUERIT CELI SOLATIA

COMPUNGITUR DURIS SENTIBUS / MUNDI CARENS DIVITIIS

ROSIS PLENA VIRENTIBUS / ...

... ANT / CELESTIS SPES ET CARITAS

ET ANGELI COADIUVANT / UT PLACEAT NECESSITAS

HANC SPONSAM CHRISTUS TRIBUIT / FRANCISCO UT CUSTODIAT

NAM OMNIS EAM RE[SPUIT]/ ...

This scene must have been inspired by the “Sacrum Commercium Beati Francisci cum Domina Paupertate”(translated in Armstrong et al. - referenced below). This literary allegory of St Francis’ discovery of the basis for his Rule centres on his “espousal” of (or perhaps “covenant” with) Lady Poverty. St Francis and his brothers earnestly sought this “queen of virtues”, whom Christ, while on earth, had adorned “as a bride with a crown”. They finally found her at the summit of the “mountain of the Lord”, and St Francis begged her: “Simply make peace with us and we shall be saved”.

Scholars date this literary source to various times in the period 1227-60. St Bonaventure seems to have drawn on it in the “Legenda Maior” (1263), when he wrote that St Francis, realising that “holy poverty” was “a close friend of the Son of God, yet was nowadays an outcast throughout almost the whole world, was eager to espouse her in everlasting love”. The work remained influential in the early 14th century, when the fresco in the vault was conceived:

-

✴In the “Arbor Vitae”, Ubertino da Casale (see below) describes the “sacred association” of St Francis with Lady Poverty, in conformity with Christ (in Book 5, Chapter 3).

-

✴In the “Divine Comedy” (ca. 1317-21), Dante describes how St Francis “fought against his father's wishes for the favour of [Lady Poverty ... and] joined himself to her and, from then on, with each passing day, he loved her more”. His early brothers, Giles and Sylvester, ran barefoot, “following the groom, so greatly pleasing is the bride” (“Paradiso”, Canto 11 - see the link referenced below).

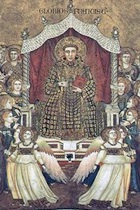

St Francis in Glory

In this fresco, which greets the faithful as they walk along the nave towards the high altar, St Francis is identified as “GLORIOS[US] FRANCISC[US]”. He is enthroned against a golden background, and pairs of angels seem to be pulling him towards the viewer.

Other musical angels surround the throne, including a pair on each side who are turned away from it, blowing the trumpets that will signal the Last Judgement after the opening of the Seventh Seal.

At the apex of the composition, a crucified seraph with two wings is set above a banner with a cross and seven stars.

Apocalyptic Significance of the Frescoes

In the vaults, the three fundamental aspects of the Franciscan Rule are depicted as showing the way to salvation. More precisely, a number of people who follow these aspects of the Rule ascend towards what seems to be an idyllic upland plateau, where they are welcomed by an angel or (as in the fresco of the allegory of Chastity, illustrated here) by St Francis. This location is reminiscent of the reference in the “

Sacrum Commercium Beati Francisci cum Domina Paupertate” to “the summit of the “mountain of the Lord”, on which St Francis and his brothers found Lady Poverty. The plateau is apparently a place in this world, below Heaven, which seems to be located: at the apex of each of the allegories of the Franciscan Rule; and in the vault containing the enthroned St Francis.

In order to understand more precisely what is portrayed here, we need to delve into the complex area of Franciscan apocalyptic thought. This must begin with the opening section of the “Legenda Maior”, in which St Bonaventure describes St Francis as the angel of the Sixth Seal, whom the author of the Book of Revelations (7:2) saw “ascending from the rising of the sun, having the seal of the living God”. The presence of the St Francis bearing the seal of the living God (i.e. the stigmata) at the liturgical east end of the lower church must have represented his identification with this angel.

The angel of the Sixth Seal played a central role in the history of salvation: specifically, he “called ... to the four angels who had been given power to damage earth and sea”, telling them to desist “until we have marked the servants of our God with a seal on their foreheads” (7:2). The account goes on to identify the 144,000 who would be saved, 12,000 from each of the 12 tribes of Israel. These saved souls also appear later in the vision: “Then I looked and there was the Lamb standing on Mount Zion. And with him were 144,000 who had His name, and the name of His Father written on their foreheads” (14:1). This again leads St Bonaventure to St Francis, whose “whole desire was .. to mark with a Tau (cross) the foreheads of those ... truly converted to Jesus Christ” (“Legenda Maior” 4:9).

But what precise form did salvation take? Early in his career, the present Pope Benedict XVI illuminated this aspect of the apocalyptic philosophy of the Franciscans in the late 13th century: as he explains on his website (in his description his postdoctoral work on St Bonaventure): “The interesting idea that I discovered was that a significant current among the [mainstream] Franciscans was convinced that St Francis of Assisi and the Franciscan Order marked the beginning of [the] third period of history, and it was their ambition to actualise it; Bonaventure was in critical dialogue with this current”. This third period of history had been conceived in the 12th century by Joachim of Fiore as “the time of the Holy of Spirit ... a time of universal reconciliation, ... a time without the law (in the Pauline sense), a time of real brotherhood in the world”.

The postdoctoral work in question was published by the then Joseph Ratzinger as “Theology of History in St Bonaventure” (referenced below). The “interesting idea” summarised above is treated there in detail: “In the eyes of Bonaventure, the situation of peace before the final storm indicated in [the Book of Revelations, chapter 7] has begun with Francis. Francis is the apocalyptic angel of the seal from whom should come the final Peace of God for the 144,000 who are sealed. This final People of God is a community of the contemplative men: in this community the form of life realised by St Francis will become the general form of life. It will be the lot of this People to enjoy already in this world the peace of the seventh day, which is to precede the Parousia [Coming] of the Lord” (pp 54-5).

The frescoes of the allegories of the Franciscan Rule seem to represent the elect People of God ascending to this place of peace in the third period of history.

Spiritual Franciscans

The iconography of these frescoes was devised at a time when a growing body of Franciscans (later known as the Spirituals) were becoming alienated from the mainstream because they wanted to follow the Franciscan Rule in its original form, as expressed in St Francis’ Testament, without the benefit of subsequent papal glosses and other interpretations that relaxed its prescriptions on poverty.

Many scholars have noted that the frescoes described above seem to reflect the eschatology of these Spirituals. However, as is clear from the above quotations from earlier works by St Bonaventure, the Spirituals did not have a monopoly on eschatological expectations. In order to determine the extent of any Spiritual influence on the frescoes, it is necessary to focus on the important difference between the two eschatological approaches:

-

✴Joseph Ratzinger noted that: “The decisive thesis of the Spirituals involved the full identification of the actual Franciscan Order (especially its Spiritual branch) with the [community of the contemplative men] of the final age” (p46).

-

✴In contrast, for St Bonaventure, the Franciscan Order represented only the Ordo Cheribicus. St Francis had belonged to the more perfect Ordo Seraphicus and, “in his own person anticipates the eschatological form of life that will be the general form of life in the future” (p 50). Ratzinger also explained the practical considerations that underlay this position taken by the Minister General: “Bonaventure recognised that Francis’ own eschatological form of life could not exist as an institution in this world: it could be realised only as a break-through of grace in the individual until ... the world would be transformed into its final form of existence” (p 51).

In the frescoes of the allegories of the Franciscan Rule, those welcomed onto the plateau are not all Franciscans. It thus seems to reflect St Bonaventure’s conception of the world transformed into its final form of existence. This is not to assert the absence of any Spiritual influence on the iconographic programme. For example, although St Bonaventure had mentioned the marriage of St Francis and Lady Poverty, Ubertino da Casale offered a more recent evocation of it.

Elvio Lunghi (reference [b] below) has suggested that the iconographer of the fresco in the apse “must have had in front of him” (my translation) the manuscript of the “Arbor Vitae”. Specifically, drawing on the text of Book 5, Chapter 4, Lunghi relates:

-

✴the attributes held by the two angels to the sides of St Francis to those suggested in Ubertino’s allegory of the stigmata:

-

•the mirror that portrayed the stigmatised St Francis as a reflection of the crucified Christ;

-

•the throne of the fallen Lucifer, which awaited the chosen St Francis (signed by the stigmata) in Heaven;

-

•the Church, which St Francis had been sent to rescue under the sign of the stigmata; and

-

•the red cloth, stained by the blood from the side wound, which symbolised the dignity that St Francis shared with Christ; and

-

✴the figure of St Francis in the pose of a protective intercessor at the time of the Final Judgement reflects Ubertino’s assertion that the presence of the stigmata would move the faithful to seek his intercession in order that they would be resurrected after death.

Lunghi also relates the columnar figure of the stigmatised St Francis in the apse to Ubertino’s gloss of Revelation 3:7-12: "And to the angel of the church in Philadelphia write: ... 'Because you have kept the word of My perseverance, I also will keep you from the hour of testing, that hour which is about to come upon the whole world ... hold fast what you have, so that no one will take your crown. He who overcomes, I will make him a pillar in the temple of My God, and he will not go out from it anymore; and I will write on him the name of My God, and the name of the city of My God, the new Jerusalem ...”.

These aspects of the “Arbor Vitae”, which may well have influenced the apse fresco, would not, of course, have been particularly controversial. In relation to the last one (the association of St Francis with the angel of Philadelphia and the pillar of the temple), David Burr translates a very similar gloss from the “Collationes in Hexamaemeron” by St Bonaventure (see p 36 of the reference below).

There is one respect in which Spiritual influence on the iconography seems to be explicit and potentially controversial: the image of St Francis enthroned and identified as “GLORIOS[US] FRANCISC[US]” recalls with the reference to his resurrection in the “

Commentary on the Apocalypse” (ca. 1298) by

Peter John Olivi:

-

“I have also heard from a very spiritual man, very worthy of belief and very intimate with Brother Leo ... [almost certainly the Blessed Conrad of Offida], something ... that I neither assert nor know nor think should be asserted: namely that ... [Brother Conrad] learned that during the pressure of that Babylonian temptation in which Francis' state and rule will be crucified ... in the place of Christ himself, he [St Francis] will rise again glorious, so that just as he was singularly assimilated to Christ in his life and in the stigmata of the cross, so he will be assimilated to him in a resurrection .... In order that the resurrection of the servant should clearly be distinguished in degree of dignity from the resurrection of Christ and His mother, however, it is said by certain people who are not entirely to be rejected that: Christ was resurrected immediately after three days; His mother after forty; and this man [St Francis] after the whole duration of his order up to its crucifixion assimilated to the cross of Christ and prefigured in St Francis' stigmata”.

I have taken the above from an online translation by Paul Halsall Jan, but it is also given by David Burr in his section of the Spirituals’ thoughts on the resurrection of St Francis (pp. 121-4).

The possibility of the resurrection of St Francis was not entirely new: St Bonaventure had observed that the stigmatised body of St Francis offered “a glimpse of the resurrection” (“Legenda Maior” 15:1). In addition, as David Burr points out, while Peter John Olivi touched on the possible resurrection of St Francis, he did so tentatively and found it to be “unproved and unprovable, yet intriguing” (see below, p 124). However, as Burr also points out, Ubertino da Casale had been much more emphatic in the “Arbor Vitae” (Book 5, Chapter 4):

-

“What I heard from [the Blessed Conrad of Offida] ... was that the blessed Francis, after his glorification in heaven, revealed to the holy Brother Leo ... that in the apparition [i.e. during the stigmatisation] Christ foretold to him the tribulations that his foundation and the Church would face, the rejection and corruption of his Rule, and how greatly upset the minds of spiritual men ... would be at this universal assault on the Rule. And that, for their comforting and enlightenment, Jesus, out of his extreme goodness, would raise him up again, in a glorified body, and cause him to appear visibly to those aforesaid children of his”. (This translation , with my italics, is from Armstrong et al. - referenced below).

That leaves the question as to whether the mainstream of the Franciscan Order would have equated “GLORIOS[US] FRANCISC[US]” with the resurrected St Francis who would appear to comfort the Spirituals. This seems unlikely: as Nick Havely points out (see below, p 78), the mainstream of the Order was still apparently unaware of the content of the “Arbor Vitae” in 1309-12. (They would otherwise surely have used its more outrageous assertions, such as the identification of Popes Boniface VIII and Benedict XI with the Antichrist, against him in the vitriolic debate that was in progress at this time).

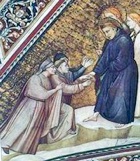

It seems more likely that, for most observers, the fresco represented no more than the realisation of the vision of Brother Pacifico that appeared for the first time in the “

Legenda Maior” (6:6) and was depicted in the upper church (illustrated here). As Brother Pacifico (who kneels at the extreme left) waited outside a deserted church in which St Francis was praying, he had a vision of many thrones in heaven, one of which was “more noble than the rest ... glittering in great glory”. As he wondered whose throne this was, a voice told him that it “had belonged to one of those who fell [i.e. Satan], and is now reserved for the humble Francis”.

On balance, it seems that the apocalyptic content of these frescoes is largely inspired by St Bonaventure, but that it was nevertheless also influenced by Ubertino da Casale. Elvio Lunghi points out that it is highly unlikely that the mainstream of the Order would have allowed overtly Spiritual iconography to be used in any Franciscan church in the early 14th century, let alone in this one. In any case, Ubertino could surely not have approved of this use of his “Arbor Vitae”, since was a vociferous critic of the sumptuous decoration of Franciscan churches. In addition, he believed that the resurrected St Francis would appear solely to the spiritual men who upheld the Rule in its original purity: yet here in the lower church, he appears at the heart of the Franciscan establishment, which (as Ubertino saw things) had rejected and corrupted that Rule.

Elvio Lunghi resolves this apparent paradox by suggesting that the person who probably conceived this iconographic programme was Cardinal Napoleone Orsini. He employed Ubertino as his chaplain from shortly after the “Arbor Vitae” was written (as noted above), and could easily have drawn on aspects of the work while ignoring its pejorative connotations. Diederik Schönau (referenced below) had earlier arrived at the same conclusion.

-

✴Schönau referred to a paper by Igino Supino, in which the figures on the left in the allegory of Obedience were tentatively identified as Brother

John of Morrovalle (in red) and St Louis of Toulouse: the former, whom Vasari asserted had called Giotto to Assisi, had also received St Louis into the Order in 1296. (He also identified the aged friar kneeling before the allegory of Obedience as Count

Guido I of Montefeltro, whom John of Morrovalle had received on the same occasion).

-

✴An alternative, which Schönau does not draw but which could follow from his analysis, is that the figures represent Cardinal Orsini (in red) and his younger brother, who was buried in the chapel at the end of the right transept (towards which the angel points).

(For the wider role of Cardinal Orsini in the decoration of the apse, crossing and transepts, see the page on San Francesco in the 14th Century).

Read more:

J. Robson, “Judas and the Franciscans: Perfidy Pictured in Lorenzetti's Passion Cycle at Assisi”, Art Bulletin, 86 (2004) 31-57

N. Havely, “Dante and the Franciscans”, (2004) Cambridge

E. Lunghi [a], “La Perduta Decorazione Trecentesca nell' Abside della Chiesa Inferiore del San Francesco ad Assisi”, Collectanea Franciscana, 66 (1996) 479-510

E. Lunghi [b], “L' Influenza di Ubertino da Casale e di Pietro di Giovanni Olivi nel Programma Iconografico della Chiesa Inferiore del San Francesco ad Assisi”, Collectanea Franciscana, 67 (1997) 167-87

D. Burr, “Olivi's Peaceable Kingdom: A Reading of the Apocalypse Commentary”, (1993) Philadelphia

D. Schönau, “A New Hypothesis on the Vele in the Lower Church of San Francesco in Assisi”, Franziskanische Studien, 67 (1985) 326-47

P. Scarpellini, “Fra Ludovico da Pietralunga: Descrizione della Basilica di San Francesco d’ Assisi”, (1982), Treviso

(pp 61-2 for the original description of the lost frescos in the apse and pp 288-92 for the related commentary by Pietro Scarpellini)

B. Zanardi, “Da Stefano Fiorentino a Puccio Capanna”, Storia dell' Arte, 22 ( 1978) 115-27

J. Ratzinger, “Theology of History in St Bonaventure” (1971) Chicago,

translated into English by Z. Hayes

I. Supino, “Giotto” (1920) Florence

M. Gosebruch, “Gli Affreschi di Giotto nel Braccio Destro del Transetto e nelle 'Vele' Centrali della Chiesa Inferiore di San Francesco”, in

G. Palumbo et al., “Giotto e i Giotteschi in Assisi” Assisi (1969) pp 129-98,

for a full description of the frescoes in the vaults as they appeared after their restoration in 1968, including a definitive version of the inscribed Latin verses that describe them.

Translations into English of some of the sources referenced above have been published as: R. Armstrong et al. (Trans.), "Francis of Assisi: Early Documents" (three volumes plus an index, respectively 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002), St Bonaventure, New York

✴Volume I contains translations of the the “Vita Prima” and the “Sacrum Commercium Beati Francisci cum Domina Paupertate”. See pp 552-3 for the ascent by St Francis and his brothers of the “mountain of the Lord” to find Lady Poverty at its summit; and their “espousal” of (or perhaps “covenant” with) her.

✴Volume II contains translations of the “Vita Secunda” and the “Legenda Maior”.

✴Volume III contains translations of: Ubertino da Casale, “Arbor Vitae Crucifixae Jesu”, Book 5. Unfortunately, the allegory of the stigmata is omitted.

•The “sacred association” of St Francis with Lady Poverty, in conformity with Christ, is described on pp 159-63.

•The quotation above on the resurrection of St Francis is on p 194.

A translation of Dante’s “Paradiso”, Canto XI is online as part of the Princeton Dante Project - choose Paradiso and then Canto XI as search criteria.

One of the pages on Giotto in the Web Gallery of Art includes excellent images of the frescoes in the vault. (Click on the image of interest and select from the enlargement options).

The figure of St Francis in the apse of the lower church clearly influenced later depictions of St Francis as “Alter Christus”. A notable example is the panel (1437-44) of St Francis in Ecstasy by Sassetta, which came from a now-dismembered double-sided altarpiece on the high altar of San Francesco, Borgo San Sepolcro. The iconography is discussed in a number of contributions to the new book described in the second of these links.

Return to the Lower Church.

Return to the main page on San Francesco.

Return to Walk III.

Return to the home page on Assisi.