The Cappella Nuova was built as an extension to the right transept of the Duomo in 1406-25, after the demolition of the old sacristy and the side chapel there.

History

An individual named Tommaso di Micheluccio left money in his will in 1396 for the construction of a chapel in the Duomo that was to house a wooden statue of the Virgin. This image had been credited by saving Orvieto from a prolonged siege in 1387-8, and the Commune had celebrated by ordering that it should be taken in procession from the Duomo to Sant’ Andrea on the Feast of the Assumption, to be returned in another procession on the following day. The tradition has been maintained to this day, albeit that the original statue has been lost (see below).

Work on the chapel, which was built between the flying buttresses abutting the right transept, was first recorded in 1408. It required the demolition of the old sacristy and the side chapel on this site, which had belonged to the Monaldeschi della Vipera (or della Sala).

The main chapel is roughly rectangular. Two shallow side chapels were subsequently established into aedicules on the side walls:

-

✴The Cappellina dei Corpi Santi on the right wall was established in 1468 to receive the relics of SS Faustinus and Peter Parenzo.

-

✴A pendant chapel was established on the left wall in ca. 1491 and dedicated as the Cappellina di Santa Maria Maddalena in ca. 1504.

These small chapels are described below.

Antonio degli Albèri, who was archdeacon of the Duomo in 1497-1503, built a new cathedral library against the right wall of the chapel in ca. 1500. This was probably in emulation of the library (1492-1502) that Albèri's friend, Cardinal Francesco Piccolomini (later Pope Pius III) had built in the Duomo, Siena (with frescoes (1502-8) by Pintoricchio).

The Cappella Nuova became known as the Cappella della Madonna di San Brizio in 1622 when a venerated panel known as the Madonna di San Brizio (see below) was moved to its main altar.

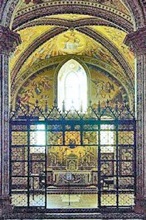

Main Altar

The wooden statue of the Virgin that was mentioned above was originally kept on the main altar of the Cappella Nuova. The Madonna di San Brizio (see below) replaced it in 1622. Unfortunately, it has since been lost.

The present baroque altar was installed in 1712-5.

Madonna di San Brizio (late 13th century)

-

✴A relic of the blood of St Peter Parenzo was inserted into a cavity that was made in the heart of the infant, probably before it was moved to the present Duomo.

-

✴An image of St Brictius was added in 1464, but it was later removed.

In 1459, Francesco Monaldeschi (who had been bishop of Orvieto in 1418-43) proposed to build an oratory to house the image. Although the Opera del Duomo was reluctant to accept money from such an unpopular figure, its dire need of funds overcame these scruples. The original plan was to instal the oratory in the Cappella Nuova. However, Francesco Monaldeschi changed his mind, and a sumptuous chapel was duly built on the counter-facade (to the right of the main entrance) soon after his death in 1461. This chapel was demolished in 1570 as part of the 16th century remodelling of the Duomo, at which point the image was incorporated into the new decorative scheme. It remained there until 1622, when it was translated with great ceremony to its current location in the Cappella Nuova. It was incorporated into the present altar in 1715.

Frescoes of the Main Chapel

Phase I (1447-9)

Towards the entrance wall

Towards the altar wall

The decoration programme started with the vault nearest the altar.

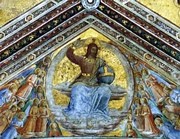

Christ in Judgment Prophets

The brothers Gentile and Arrigo Monaldeschi della Vipera, who ruled Orvieto in the period 1435-49, probably sponsored the initial phase of the decoration of the chapel. The Opera del Duomo consulted Francesco Baroni, who was was working on the stained glass of the Duomo in 1446, and he recommended Fra Angelico. The Opera del Duomo duly negotiated a contract in which Fra. Angelico agreed to spend three months in each summer of 1447-9 in Orvieto. The contract described him as ‘famosus ultra omnes pictores italicos’ (more famous than any other artist in Italy). Fra Angelico was consulted about the subject matter, and he suggested the Last Judgement.

Fra. Angelico arrived in Orvieto in June 1447, together with his assistant Benozzo Gozzoli and two apprentices: Giovanni Antonio da Firenze and Giacomo de Poli. The Opera del Duomo put the local painter Pietro di Nicola Baroni at his disposal. Fra Angelico and his team frescoed two of the four sections of the vault nearest the altar, which depicted:

-

✴Christ in Judgment; and

-

✴the Prophets.

Fra Angelico left Orvieto for Rome in September 1447, as allowed for in his contract. However, the demand for his services in Rome from Pope Nicholas V meant that he never returned, although some minor work was subsequently carried out by his assistants. Two of these subsequently offered to take over from Fra Angelico, but were declined:

-

✴Pietro di Nicola Baroni, in May 1449; and

-

✴Benozzo Gozzoli, in July 1449.

Work probably stopped completely in December 1449, when Arrigo Monaldeschi was murdered and Gentile Monaldeschi was driven into exile.

Second Phase (1482-99)

Very little progress seems to have been made in the three decades after 1449, with the exception of a fresco (1468) in the Cappellina dei Corpi Santi by Pietro di Nicolà Baroni (see below). However, in the early 1480s, the search began for the most suitable artist to take over the project. Unfortunately, as set out below, that proved to be far from straightforward.

Pier Matteo d’ Amelia (1482-90)

The Opera del Duomo made a series of payments to Pier Matteo d' Amelia in 1480-1 for what seem to have been fairly minor individual commissions. He did, however, prove his abilities during this period in Orvieto with the Sant’ Agostino Polyptych (1481). In February 1482, the Opera del Duomo urged him to start work on the Cappella Nuova as soon as possible, in line with a previously-agreed contract. He is documented as buying materials in Rome for the account of the Opera del Duomo in 1489-90, but he seems never to have started work on the project.

Perugino (1489-99)

On November 1489, the Opera del Duomo, at the instigation of the Camerlengo (Chamberlain) Antonio Simoncelli, resolved to complete the decoration of the chapel, since its current state was “a great disgrace” for them. Some six weeks later, “master Pietro Perugino, a painter famous throughout Italy”, who was then in Orvieto to discuss the project, was appointed to complete the vaults.

However, despite a series of pleas from the Opera del Duomo, Perugino proved elusive, except for short visits to Orvieto in March/April and September/October 1491. The relevant documents for the latter visit include a reference to “Andreas alias Ingegnio, famulus ... magistri Petri” (Andrea d’ Assisi, l’ Ingegno, apprentice of Perugino). A fresco of St Michael from the Cappellina di Santa Maria Maddalena, which no longer survives but which is known from photographs, is sometimes attributed to him (see below).

The Opera del Duomo sent a letter to him in 1492, threatening to appoint another artist in his stead, to which Perugino’s Roman patron Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere (the future Pope Julius II) replied in equally strident terms. Despite numerous subsequent requests, Perugino never returned to Orvieto, and the Opera del Duomo seem to have finally abandoned hope in March 1499, when a final written appeal to Perugino to return to Orvieto received a negative reply.

Antonio da Viterbo, il Pastura (1498)

Antonio da Viterbo, il Pastura, who restored some of the frescoes in the tribune in 1497-9, was considered as a replacement for Perugino in 1498, but this idea was subsequently rejected.

Phase IIIa (1499)

Angels with the instruments of the Passion Virgin and the Apostles

In April 1499, only a month after its final appeal to Perugino, the Opera del Duomo signed a contract with Luca Signorelli for the completion of the vault nearest the altar, following drawings left behind by Fra. Angelico. Much of the decoration of the ribs was already in place, and Signorelli completed the last two vanes in only six months. These depict:

-

✴angels with the instruments of the Passion (opposite Christ in Judgment); and

-

✴the Virgin and the Apostles.

As noted above, Perugino might have already painted two of the angels on the first of these scenes.

Phase IIIb (1499-1500)

Entrance wall

The Opera del Duomo then unanimously agreed to commission Signorelli to paint the second vault of the chapel, and consulted local theologians as to the content. These scenes depict “choruses” of specific categories of saints:

-

✴virgins (nearest the entrance wall);

-

✴patriarchs;

-

✴martyrs; and

-

✴confessors.

The first of these scenes contains two sets of Monaldeschi arms, which probably reflect the bequest of 100 florins mandated by Pietro Antonio Monaldeschi in his will of 1488. His widow, Giovanna Monaldeschi transferred this sum to the Opera del Duomo in 1500 and the money would have covered about a quarter of that due to Luca Signorelli for Phase IIIb.

Phase IV, the Last Judgement (1500-4)

Preaching of the Antichrist End of the world Resurrection of the dead

Entrance wall

Assembly of the elect Ascent of the elect: expulsion of the damned Punishment of the damned

Altar wall

In early 1500, as work on the vaults of the chapel was nearing completion, Signorelli submitted his plans for its walls to the Opera del Duomo. These were duly accepted, albeit not unanimously, and Signorelli was commissioned to carry out the work.

Although the subject of the wall frescoes was clearly predetermined when Fra’ Angelico frescoed Christ in judgment above the altar, it was made more poignant by the plague that ravaged Orvieto at the start of the new century. Luca Signorelli dramatically captured the millennial fervour that gripped the city. Giorgio Vasari (who was related to Luca Signorelli and had childhood memories of him as an old man) recorded that Signorelli: “painted all the scenes of the end of the world with bizarre and fantastic invention: angels, demons, ruins, earthquakes, fires, miracles of the Antichrist, and many other similar things besides, such as nudes, foreshortenings, and many beautiful figures; capturing the terror that there shall be on that last and awful day. ... I do not marvel that the works of Luca were ever very highly extolled by Michelangelo, nor that in certain parts of his Divine Judgement, which he made in the [Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo] should have deigned to avail himself in some measure of the inventions of Luca, ... as all may see”.

The cycle depicts the events that were expected at the approach of the Day of Judgement:

-

✴The scenes in the entrance bay depict the events of the Last Days:

-

•To the right of the entrance, the Antichrist preaches outside the Temple in Jerusalem, a building modelled on the then-current plans for St Peter’s, Rome. (Signorelli painted himself and Fra’ Angelico among the listeners, at the far left.)

-

•Above the entrance are the signs that signal the end of the world, taken from the Book of Revelations. (The arms of the Opera del Duomo are at the centre.)

-

•To the left of the entrance, the dead arise to face judgment.

-

✴The scenes in the altar bay depict the Last Judgement itself:

-

•On the altar wall, immediately below Fra’ Angelico’s Christ in Judgement, the elect are assembled to His right while the damned are herded to His left.

-

•In the next lunette on the left wall, the elect reach paradise.

-

•In the next lunette on the right wall, the damned pass through purgatory into hell.

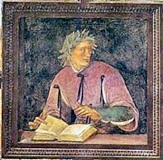

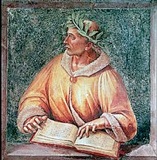

Dante Ovid Virgil

The lower part of the walls contains imaginary portraits of literary figures, including:

-

✴Virgil, surrounded by four grisaille scenes from the Georgics and the Aenid;

-

✴Ovid, surrounded by four grisaille scenes from the Metamorphoses; and

-

✴Dante, surrounded by four grisaille scenes from the Purgatorio (part of the Divine Comedy).

In 1505, Tradita Colonna, the widow of Achille di Baccio Monaldeschi, paid at least two instalments from a bequest of 100 florins that her husband had made in 1494 towards the decoration of the chapel. This bequest was to be paid within two years of his death, which occurred in 1497. However, the only documented payments, bot of 20 florins, were made in 1505. It is possible that earlier instalments had been used to cover some of the costs of Phase IV.

Unfortunately, parts of this lower cycle are lost:

-

✴The lower part of the altar wall was obscured when the present altar was installed in 1712-5.

-

✴The portrait in this series on the left of the entrance wall was destroyed in 1717 when the monument to Cardinal Ferdinando Nuzzi was erected. (He had been given the personal title of Archbishop of Orvieto in 1715). The monument was subsequently removed.

Art from the Chapel

Luca Signorelli and Nicolò d' Agnolo Franchi (1504?)

St Constantius (1593-6) and St Brictius (1601)

St Constantius (1593-6) St Brictius (1601)

These marble figures by Fabiano Toti originally flanked the altarpiece of the Madonna della Stella. They were documented in 1632 on the counter-facade of the Duomo. They are now exhibited in the ex-church of Sant’ Agostino.

Cappellina dei Corpi Santi (1468)

This chapel is so-called because it was built to receive the relics of St Faustinus and St Peter Parenzo, two of the patron saints of Orvieto. A series of documents point to a resurgence in their cults at this time:

-

✴four payments were made in March-August 1468 for a “cassa dei corpi santi”, a new painted wooden sarcophagus for the relics of the two saints;

-

✴their two reliquaries were taken in procession around the city in September, presumably as part of their translation to the new sarcophagus;

-

✴a week later, payments were made for the altar of the Cappellina dei Corpi Santi;

-

✴the completion of this small chapel, off the right wall of the Cappella Nuova, was celebrated in October 1368;

-

✴a week later, payments were made (inter alia) for the sealing of the new sarcophagus and for a new fresco by Pietro di Niccolò Baroni (see below) for the chapel;

-

✴two weeks later, payment was made for a grating to protect the relics from over-excited worshippers; and

-

✴payments for lamps and candles for the chapel continued into 1369.

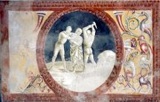

Pietà with SS Faustinus and Peter Parenzo (ca. 1504)

Martyrdom of St Faustinus Martyrdom of St Peter Parenzo

The contract between the Opera del Duomo and Luca Signorelli of 1500 included the redecoration of the Cappellina dei Corpi Santi. Payment for the building of a wall in front of the existing fresco (see below) is recorded in 1502-3. The new fresco, which was executed on this wall, depicts the Virgin's lamentation over the Dead Christ with St Mary Magdalen, St Faustinus and St Peter Parenzo. The scene is set in front of a sarcophagus that contains a fictive relief of the Deposition of Christ. Scenes of the martyrdoms of SS Faustinus and Peter Parenzo are depicted in tondi in the shallow sidewalls of the chapel.

Art from the Cappellina dei Corpi Santi

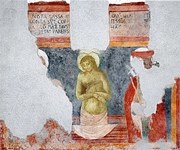

Pietà with SS Faustinus and Peter Parenzo (1468)

As noted above, Pietro di Nicola Baroni was paid to paint this fresco in the Cappellina dei Corpi Santi in 1468. The inscription above, which is in two columns, commemorates St Faustinus and St Peter Parenzo, intercessors for the city, whose bodies lay in the “cassa dei corpi santi” (a new wooden sarcophagus) in the chapel. It reads:

IN ISTA CASSA R[E]

CONDITA SUNT CORP[O]

RA SANCTORUM MARTIRUM FAUST

[INI] ET PETRY PARENS[I]

QUORUM MERITIS INTER

CESSIONIBUS DEUS [CIVITATEM]

HANC [ELUIT] [...]

The fresco, which depicted the two saints flanking an image of the Pietà, was covered by a wall in 1502-3, but partially recovered and detached during the restoration of the chapel in 1996. It is now in the Museo dell' Opera del Duomo.

Pietà (1570-9)

-

✴the Pietà (1499), which was conceived for an altar in the funerary chapel of Cardinal Jean Bilherès in Santa Petronilla, Rome and is now in St Peter’s, Rome; and

-

✴the Pietà (ca. 1550), which was probably intended for Michelangelo's own funerary monument and which is now in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence.

The commission was given to Raffaello da Montelupo, but by the time that the marble for the work arrived in Orvieto (in 1570), he was dead. The commission therefore passed to his successor, Ippolito Scalza.

The group comprises the dead Christ and Madonna with St Mary Magdalene and Nicodemus. It is carved from a single block of marble (except for the left arm of Nicodemus and the upper part of the ladder that he is holding). Scalza signed the base of the completed work in 1579.

Unlike the earlier works by Michelangelo, the Orvieto Pietà was commissioned with no particular function and no specific location in mind. Given the Eucharistic significance of the work, it is surprising that it was never incorporated into the iconographical programme of the body of the church. It was instead "provisionally" installed in front of the fresco of the Pietà by Luca Signorelli in the Cappellina dei Corpi Santi.

The sculpture immediately became the main object of devotion in the chapel, and over-shadowed Signorelli's frescoes there. Scalza wrote to the Opera del Duomo in 1588 pleading for a more appropriate location to be found, not least because the work was vulnerable to damage. This plea went unheeded, and the chapel had to be locked in 1590 to ensure that the sculpture was not damaged. In 1609 (during the debate about the location of the figures of the Annunciation by Francesco Mochi), it was decided that it should be placed in front of the tabernacle on the high altar, but this plan was never put into effect. The group remained in the Cappella Nuova until early in the 20th century, when it was moved to its current location at the junction of the nave and the right transept.

Cappellina di Santa Maria Maddalena (ca. 1491)

The decorative programme for this chapel was not specified in the contract signed with Luca Signorelli in 1500, at which time it already contained a fresco of St Michael (see below). In May 1504, shortly after St Mary Magdalene had been adopted as a patron saint of Orvieto, the Opera del Duomo decided to commission an altarpiece depicting her. Two months later, it was decided that this would be placed in what became the Cappellina di Santa Maria Maddalena. The altarpiece by Luca Signorelli (see below) probably obscured the earlier fresco in the chapel.

The Giulio Gualterio acquired the chapel in 1603. However, it remained largely in tact until 1722, when Cardinal Filippo Antonio Gualterio received permission to rebuild the altar. The the original altarpiece was replaced in 1724(see below). By the time that the project was completed in 1736, stucco work covered the flanking frescoes (ca. 1504) of SS Lazarus and Martha by Luca Signorelli and/or his workshop. The altar was dedicated to SS John the Baptist and Agnes in 1637.

The chapel contains some interesting funerary inscriptions:

-

✴Two black marble slabs on each side of the altarpiece commemorate members of the family. The most interesting of these is the first on the left, which commemorates Cardinal Filippo Antonio Gualterio (died 1728).

-

✴A fifth inscription on the floor in front of the altar commemorates Giovanni Battista Gualterio (died 1729).

These inscriptions of 1728-9 record the links between the Gualterio family and the exiled King (or Pretender) James III of England (see the website "Jacobite Heritage"), who:

-

✴invested Giovanni Battista Gualterio as Earl of Dundee in 1705; and

-

✴appointed Cardinal Filippo Antonio Gualterio as his ambassador of the to the papal court and as Cardinal Protector of Scotland (from 1706) and England (from 1717).

Altarpiece (1724)

Art from the Cappellina di Santa Maria Maddalena

St Michael (late 15th century)

This fresco, which is illustrated in the site of the Fondazione Federico Zeri, was found when the Gualterio family removed the altarpiece of the chapel in 1653 (see below). It was subsequently detached and moved to the chapel in the family palace. It was documented among the family’s possessions in 1741. It was sold in 1872 and found its way to the Museum of Fine Arts, Leipzig, where it was destroyed in the bombardment of 1943.

The fresco, which was long thought to be the work of Luca Signorelli, has recently been attributed to Andrea d' Assisi, l' Ingegno: as noted above, he was documented at work with Perugino in the Cappella Nuova in 1491. It is possible that he painted this fresco in a bid to secure the commission to complete the decoration of the chapel. If so, it seems that the initiative failed. (See R. Mencarelli, referenced below, pp 88-9).

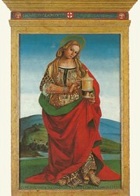

St Mary Magdalene (1504)

This altarpiece, which is by Luca Signorelli, depicts St Mary Magdalene standing in a landscape. It is painted on wood and might have been originally conceived as a processional banner. The inscription along the bottom of the panel records that the Conservatori della Pace (the elected officials who were charged with maintaining peace between the city’s factions) commissioned the work, which was dedicated to “she who keeps the peace”, and gives the date 1504. The lintel of the frame bears the names of two of the commissioning magistrates, “CECCARELLUS DE ADVIDVTIS ET RVFINVS ANTONII, together with their arms and those of the Commune.

Read more:

G. Testa (Ed.), “La Cappella Nuova o di San Brizio nel Duomo di Orvieto”, (1996) Milan. Two articles are particularly relevant to the material here:

R. Mencarelli, “Intermezzo: Piermatteo d’Amelia, Perugino, Antonio del Massaro e Pinturicchio”, pp 87-94

G. Testa, “La Cappellina dei Corpi Santi e la Cappellina della Maddalena”, pp 269-76

D. McLellan, ‘The Cappella Nuova at Orvieto before Signorelli: Perugino and the Opera del Duomo; a Question of Commitment’, Studi di Storia dell’ Arte, 7 (1996), 307-32

The literature on Signorelli’s frescoes is extensive. I made particular use of:

D. McLellan, “Signorelli’s Orvieto Frescoes: a Guide to the Cappella Nuova of Orvieto Cathedral”, (1998, reprint 2000) Perugia (available in the Duomo)

See also

D. McLellan, “New Documents for Signorelli's Commissions in Orvieto Cathedral”, Burlington Magazine, 147 (2005) 34-7

Return to the main page on the Duomo.

Continue to: Crypt.

Return to: Exterior; Facade; Interior; 16th Century Remodelling;