Pope Gregory IX wrote two letters on consecutive days in January 1236 that seem to relate to the foundation of this nunnery:

-

✴The first was sent to a group of women in Perugia who wished to serve God in the Cistercian Order. It gave them permission to establish a nunnery in Perugia "in loco qui dicitur Sancta Maria" in honour of St Elizabeth of Hungary, whom he had canonised in 1234 at San Domenico (later San Domenico Vecchio).

-

✴The second was addressed to the Archpriest of the Duomo of Perugia and to the friars of San Domenico there. It referred to a number of men from Perugia who had recently entered the monastery of San Salvatore di Monte Acuto (which Gregory IX had transferred to the Cistercian Order in 1234) and who wished to use their possessions to build a nunnery for their female relations and other women who wanted to escape from the vanities of the world.

A few months later, Gregory IX wrote to a group of women from Perugia, confirming the transfer to them by the Abbazia di San Salvatore of the nearby church of Santa Giuliana di Monte Acuto. It is tempting to assume that this was the group of women referred to in the earlier letters, and that the earlier plan for a nunnery in Perugia had fallen through.

In 1248, a lady called Benvenuta di Cilino di Assisi made bequests to a number of nunneries in Perugia:

-

✴Santa Caterina (later Santa Caterina Vecchia);

-

✴Sant’ Angelo di Arenaria (or del Renaio), near Cenerente (some 4 km outside Porta Sant' Angelo), which later transferred to San Francesco delle Donne;

-

✴Santa Margherita; and

-

✴Santa Giuliana.

This suggests that Santa Giuliana was also, by that time, in Perugia, presumably on the present site.

The existence of this nunnery comes sharply into focus in 1253, when Pope Innocent IV wrote a series of letters taking it under papal protection. This seems to have been at the instigation of John of Toledo, the English Cardinal Protector of the Cistercians, whom Innocent IV names as the founder of the nunnery. From these, it is clear that their church was dedicated to the Virgin as well as to St Juliana, suggesting that it had indeed been built "in loco qui dicitur Sancta Maria". In 1254, the nunnery was accepted as subject to the Cistercian Abbazia di San Galgano, near Siena.

In 1257, the nuns Santa Giuliana, Perugia gave the church of Santa Giuliana di Monte Acuto to the Abbazia di San Salvatore, and received in exchange the church of Sant’ Egidio di Colle.

Santa Giuliana attracted the patronage of the nobles of Perugia (who appreciated it as a home for their daughters) and it became one of the richest and most powerful nunneries in Umbria. In 1376, the Abbess, Gabriella Bontempi secured the relic of a fragment of the head of St Juliana of Nicomedia from San Domenico. (She might well have used the influence of her brother, Bishop Andrea Bontempi.)

The complex was threatened with demolition in 1547 to to make way for the Fortezza di San Cataldo, part of the new Rocca Paolina. They bought a site in what is now Corso Cavour from the nuns of San Francesco delle Donne and commissioned Galeazzo Alessi to design a new church and nunnery; a payment that they made to him in 1548 relates to the preparation of a design and a model. Cardinal Tiberio Crispo laid the foundation stone of the church, which was dedicated to St Bernard. The planned Fortezza di San Cataldo was reduced in scale when Rocca Paolina was redesigned. The nuns' fears for Santa Giuliana were therefore not realised, and they never moved here. (The site subsequently passed to the nuns of Santa Caterina).

Santa Giuliana became notorious in the 16th century for the scandalous behaviour of its nuns, many of whom were placed there by their families and lacked religious vocations. The community inevitably attracted the attention of the Counter-Reformation papacy. In 1567, Pope Pius V severed its connections with the Cistercians and placed it under the jurisdiction of the bishops of Perugia.

The church was subsequently re-modelled and re-consecrated on two occasions:

-

✴in 1595, by Bishop Napoleone Comitoli; and

-

✴in 1750, by Bishop Francesco Riccardo Ferniani.

The nunnery was suppressed in the Napoleonic period, when the church was used as a granary. It was subsequently re-opened until ca. 1862, when the nuns moved to Santa Maria di Monteluce. The convent then became a military hospital, and it remains in military ownership.

The church was re-opened in 1937. Its lovely Gothic façade and campanile have been well restored. It is open for Mass each Sunday morning and can alternatively be visited, together with the nunnery, by appointment.

Ancient History of the Site

Grave goods from a number of Etruscan tombs (4th century BC) that were excavated here in 1932-5 are exhibited in the Museo Archeologico.

Interior of the Church

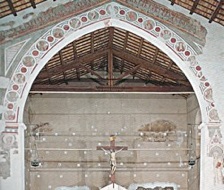

The interior is in the form of a rectangular room with a tie-beamed ceiling. A large triumphal arch and a double altar separate what was the nuns’ choir from the space for the congregation.

Frescoes on the Triumphal Arch (ca. 1295)

These comprise:

-

✴two frescoes below and to the sides:

-

•St Juliana, on the left; and

-

•St Bernard of Chiaravalle (the founder of the Cistercians) holding the Rule of the Order; and

-

✴a “chain” of tondi connecting them, which contain a series of six angels on each side and, at the top, the Lamb of God flanked by the symbols of the Evangelists.

There is a close similarity between this arrangement and that of the frescoes on the arch of the apse of the Cistercian monastery of San Salvatore di Monte Acuto (which, as noted above, had close links to Santa Giuliana in the 13th century). Mirko Santanicchia (referenced below) suggests that the frescoes at Santa Giuliana date to ca. 1295, and that the same artists then executed those at San Salvatore.

Frescoes on the Left Wall

Frescoes of the back wall of the choir (late 14th century)

The upper part of this wall in the nuns’ choir seems to have hosted a large composition, but only traces remain. There are however more substantial remains of later votive frescoes below:

-

✴A fragment to the left depicts an angel telling St Galganus (a soldier) to plunge his sword into a rock on Monte Siepe, thereby changing it into a cross, as a precursor to becoming a hermit. He died in 1181 and the Cistercian abbey of San Galgano was built on the site some 20 years later. (This interpretation is given by Augusto Staccioli in A. Staccioli and G. Zanzotti, referenced below. As noted above, Santa Giuliana was affiliated to San Galgano from 1254).

-

✴A fragment to the right depicts the Madonna del Latte, St John the Baptist and a Cistercian saint.

Memorial Slab (1394)

Nunnery

Enclosed Choir

This room behind the apse of the “public church” was used by the nuns during services. It was plastered and forgotten until its frescoes came to light during the restorations following the earthquake of 1997.

Scenes from the Passion (ca. 1300)

These recently re-discovered frescoes depict:

-

✴the Flagellation of Christ;

-

✴the Crucifixion (illustrated in A. Staccioli and G. Zanzotti, referenced below); and

-

✴the Deposition.

Cloister (ca. 1375)

Some of the other interesting capitals in the cloister are illustrated above.

Frescoes (early 15th century)

The monochrome frescoes around the cloister are in two registers and in alternating ochre and green tones. they depict:

-

✴scenes from the life of Christ (in the upper register); and

-

✴scenes of monastic life (in the lower register).

Corridor above the Cloister

Frescoes from the Refectory (late 13th century)

These frescoes depict:

-

✴the Last Supper; and

-

✴the Coronation of the Virgin, which is attributed to the Maestro del Trittico Marzolini. (For more information on this interesting iconography, in which the Virgin places her head on the shoulder of Christ, see this website by Andrea Lonardo).

Other Detached Frescoes from the Nunnery (14th century)

These frescoes depict:

-

✴the Crucifixion with the Virgin, SS Mary Magdalene and John the Evangelist and another female saint [St Elizabeth of Hungary?], which came from a small room next to the nuns’ parlour (see below): and

-

✴a female saint holding a lash and a book, and two surviving scenes from her life. [This figure is traditionally referred to as St Theodora of Genoa, but no such saint seems to exist??]

Scenes from the Life of St Bernard (ca. 1700)

These two large panels, which originally flanked the high altar of the church, are attributed to Giuseppe Laudati. They depict:

-

✴St Bernard visited by his sister, Humbeline (after which she gave up her worldly life and obtained her husband’s permission to become a nun); and

-

✴St Stephen Abbot welcoming St Bernard to Citeaux in 1113.

Chapter Room

This room, which is one of the oldest in the complex, now serves as the office of the Generale Comandante. Four columns support its splendid vaulted ceiling.

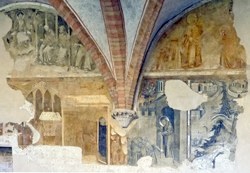

Frescoes (13th century)

These damaged frescoes in the lunettes around the room include depictions of:

-

✴the Annunciation (of which only vestiges survive);

-

✴the Baptism of Christ (illustrated in A. Staccioli and G. Zanzotti, referenced below); and

-

✴St John the Baptist and Christ.

Crucifixion (13th century)

This detached fresco, which is attributed to the Maestro di Santa Giuliana, came from the nuns’ parlour (below). It depicts the Crucifixion with the Virgin and St John the Evangelist. SS Andrew and John the Baptist stand to the sides, together with a kneeling figure of a nun who presumably commissioned the work.

St Christopher (13th century)

This fresco is in the vestibule of the Chapter Room.

Nuns’ Parlour

Assumption of the Virgin (1469)

This fresco, which is attributed to Bartolomeo Caporali, was originally part of a larger cycle. The inscription on the fictive marble underneath gives the date and the name of the nun who commissioned it: Sister Benedetta. It was detached in 1862 and subsequently exhibited in the Galleria Nazionale. However, it was restored in 2009 and returned to its original location.

-

✴In the main panel, the Virgin and Christ are enthroned in clouds above an empty tomb, surrounded by angels.

-

✴In the vault above, God the Father is depicted in a tondo.

-

✴The predella contains half-length figures of SS Juliana, Benedict and Bernard, identified by inscriptions.

-

✴the Lamb of God (illustrated here); and

-

✴a half-length figure of Christ the Redeemer.

A fresco (13th century) of the Crucifixion that was detached from one of the lunettes in this room is now in the Chapter Room (above).

Works Removed from Santa Giuliana

Santa Giuliana Dossal (1291)

This dossal, which is signed and dated by inscription, is the only known work by Vigoroso da Siena, and is the earliest surviving work in Perugia by a "foreign" artist. Its iconography suggests that came from Santa Giuliana, albeit that it belonged to the Collegio della Mercanzia in 1879, the date at which it entered the Galleria Nazionale.

The dossal depicts the Madonna and Child with SS Mary Magdalene, John the Baptist, John the Evangelist and Juliana (who is identified by inscription). Christ in Glory is depicted above the Madonna and Child, and an angel is depicted above each of the saints.

The format of the dossal is intermediate between early dossals (in which the figures occupied a single field) and later polyptychs (in which the figures occupied separate panels). Thus, while it is made up of horizontal rather than vertical planks:

-

✴carved arches separate the figures in the lower register, and

-

✴the figures in the upper register are arranged in five distinct gables cut into the upper plank.

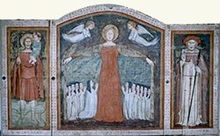

Fresco from Santa Giuliana (1376)

This frescoed triptych, which is the autograph work of the Maestro di Santa Giuliana, was detached from the Chapter Room at the base of the campanile in the 1870s. The inscription reveals that the Abbess Gabriella Bontempi commissioned it to commemorate the donation of the relics of St Juliana to the nuns by the monks of San Domenico (see below). The fresco was displayed in the church in the period 1941-54 and was subsequently moved to the Galleria Nazionale.

The main scene depicts St Juliana protecting the nuns, who kneel under her cloak, with a flying angel to each side. The nun immediately to the left of St Juliana is presumably Gabriella Bontempi, and the smaller kneeling male figure behind her might have been the nuns' chaplain. The other compartments depict:

-

✴St Christopher carrying the baby Jesus across a river (on the left); and

-

✴Cardinal John of Toledo, the founder of the nunnery (on the right).

Tabernacle for the Reliquary of St Juliana (ca. 1376)

Lower part of reliquary (1376) Upper part of reliquary (1852)

This gilded copper tabernacle from Santa Giuliana, which was probably commissioned from a Sienese workshop, originally contained a reliquary that in turn contained a piece of the skull of St Juliana.

The relics of this saint had been translated from Cuma to Naples in 1207, and this fragment subsequently passed into the possession of the friars of San Domenico. They enclosed it in a reliquary bust (ca. 1376) of the head of St Juliana, which was inscribed with the additional information that it had been made in Rome by Master William.

In 1376, Bishop Andrea Bontempi persuaded the friars to give the relic and its reliquary to the nuns of [what was then the Monastero di Santa Elisabetta, where his sister, Gabriella was the Abbess. The nuns changed the dedication of their nunnery to Santa Giuliana at this time. Check] They also commissioned this tabernacle to enclose the reliquary: the inscription records that the friars had made a gift of the reliquary that it housed “of their own free will and with honour”.

An inscription on the upper part of the tabernacle records that Abbess Ermelinda Montesperelli commissioned it as a replacement for the upper part of the original in 1852: the gallery attribute this part of the reliquary to Nicola Benvenuti and Diomede Martelli. The lower part of the tabernacle seems to have been heavily restored at this point.

The nuns removed the reliquary from the tabernacle in the Napoleonic period so that both could be hidden. The nuns took these precious possessions with them when they moved from Santa Giuliana to Santa Maria di Monteluce in ca. 1862.

-

✴The tabernacle was subsequently moved to the Galleria Nazionale, and was included in an exhibition held in 1907.

-

✴The reliquary that it originally housed appeared on the market in 1933 and subsequently found was bought by the Metropolitan Museum, New York in 1961.

Frescoes from Santa Giuliana (ca. 1380)

These two frescoes, which were detached before 1878 from a lunette in the nunnery depict:

-

✴the Nativity; and

-

✴the Adoration of the Shepherds.

They are now in the Galleria Nazionale.

Martyrdom of St Juliana (late 14th century)

This fresco, which from a lunette in the nunnery, was detached in 1862 and entered the Galleria Nazionale a year later. It depicts St Juliana hanging by her hair. She is comforted by an angel, while three men inflict further tortures: one pours molten lead over her while the other two beat her with clubs.

Polyptych (1438)

The inscription records that the Abbess Antonia di Francesco Buccoli commissioned this polyptych from Domenico di Bartolo in 1438. It was transferred from the choir of Santa Giuliana to the Galleria Nazionale. in 1863.

The altarpiece is in the form of a conventional polyptych, but the use of triangular gables above the main panels seems to pay homage to the format of work that it probably replaced on the high altar: the dossal (1291) by Vigoroso da Siena (above).

-

✴The central panel depicts the Madonna and Child, with Christ blessing in the gable above. The Abbess Antonia di Francesco Buccoli is shown kneeling before the Madonna and Child.

-

✴The other main panels depict (from the left):

-

•St Benedict, with St Peter in the gable above;

-

•St John the Baptist, with the angel of the Annunciation in the gable above;

-

•St Juliana of Nicomedia (with a winged dragon), with the Virgin Annunciate in the gable above; and

-

•St Bernard, with St Paul in the gable above.

-

The iconography of St Juliana is striking: she is often depicted leading a winged demon by a chain, but in this case the chain seems to be attached to her navel through a hole in her gown.

-

✴The predella panels , which depict scenes from the life if St John the Baptist, constitute one of the earliest surviving examples of the use of perspective in painting in the city.

St John the Evangelist Altarpiece (ca. 1518)

The panels depict:

-

✴God the Father (in the lunette)

-

✴St John the Evangelist writing his gospel on the island of Patmos (in the main panel); and

-

✴scenes from the life of St John the Evangelist (in the predella).

Madonna and Child with saints (1532)

This altarpiece, which is signed by Domenico Alfani and dated by inscription, came from Santa Giuliana. Agostino Tofanelli, the Director of the Musei Capitolini took the altarpiece to Rome in 1811, and it was returned to the church in 1815. It was transferred to the Galleria Nazionale in 1863 and now in deposit there.

-

✴The main panel depicts the Madonna and Child enthroned with SS John the Baptist and Juliana.

-

✴The predella depicts scenes from the martyrdom of St Juliana.

Read more:

G. Casagrande and P. Monacchia, “Il Monastero di S Giuliana a Perugia nel XIII Secolo”, Benedictina 27 (1980) 509-71

A. Staccioli and G. Zanzotti, “Vivere e Conoscere: Santa Giuliana: Storia, Arte, Fotografia del Complesso Monumentale”, (2010) Perugia

For the frescoes on the arch of the church, see:

M. Santanicchia, “Gli Affreschi dell' Abbazia di San Salvatore di Monte Acuto: Riverberi Giotteschi sulla Pittura Perugina tra fine Duecento e inizio Trecento”, in

N. d’ Acunto and M. Santanicchia (Eds), “L’ Abbazia di San Salvatore di Monte Acuto-Montecorona nei Secoli XI-XVIII: Storia e Arte”, (2011) Perugia, pp 201-18

Return to Nunneries of Perugia.

Return to Monuments of Perugia.

Return to Walk VII.