Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

M. Claudius Marcellus and the Spolia Opima (220 BC)

Linked Pages: Spolia Opima;

Romulus and the Spolia Opima; A. Cornelius Cossa and the Spolia Opima (437, 428 or 426 BC);

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

M. Claudius Marcellus and the Spolia Opima (220 BC)

Linked Pages: Spolia Opima;

Romulus and the Spolia Opima; A. Cornelius Cossa and the Spolia Opima (437, 428 or 426 BC);

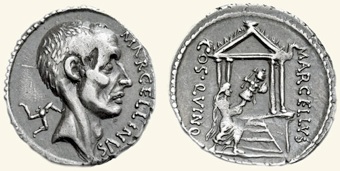

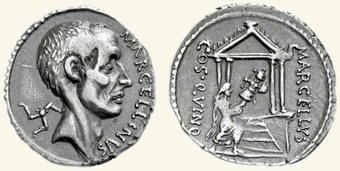

Denarius (RRC 439/1) issued in Rome, probably issued by [P] Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus in ca. 50 BC

Obverse: MARCELLINVS; head of M. Claudius Marcellus (with triskele behind, for his capture of Syracuse)

Reverse: MARCELLVS COS·QVINQ (for his five consulships):

Marcellus carries the spolia opima (which he won in 222 BC) into the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius

In about 50 BC, a moneyer who identified himself as ‘Marcellinus’ issued a denarius (RRC 439/1) in Rome that commemorated his ancestor, Marcellus, five times consul. The ancestor in question could only have been M. Claudius Marcellus (cos 222, 215, 214, 210, 208 BC), but just for the avoidance of doubt, ‘Marcellinus’:

✴placed Marcellus’ portrait on the obverse (probably copied from his death-mask) and placed triskele behind it in memory of his capture of Syracuse as proconsul in 212 BC;

✴depicted him on the reverse as he approached the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius, carrying the spolia opima that he had taken as consul from a Gallic commander at Clastidium (see below) in 222 BC.

I discuss the circumstances in which ‘Marcellinus’ issued these coins below. However, we should first look at the circumstances in which Marcellus went down in history as (among other things) the second and last man after Romulus to win the spolia opima.

Marcellus’ Career to 222 BC

According to Plutarch:

“Marcus Claudius, who was five times consul of the Romans, was a son of Marcus (as we are told) and, according to Poseidonius, was the first of his family to be called Marcellus, which means ‘martial’ ”, (‘Life of Marcellus’, 1: 1).

In fact, two earlier men of this name are recorded in the fasti:

✴M. Claudius Marcellus, son of Caius, was consul in 331 BC and dictator (for holding elections) in 327 BC; and

✴another M. Marcllus, who would have been either his son or his grandson, was consul in 287 BC.

However, the man under discussion here was the first of this line for whom any military exploits are recorded in our surviving sources. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 597) suggested that he, like all of the later Marcelli, is likely to have been a descendant of the consul of 331 BC.

Plutarch recorded that the young Marcellus had:

✴saved the life of his half-brother, T. Otacilius Crassus, in a battle in Sicily, presumably during the latter stages of the First Punic War (264 - 241 BC); and

✴subsequently served as curule aedile (probably in or shortly before 225 BC).

However, Marcellus does not appear in our surviving sources as a military leader of any importance before 222 BC, when he was elected to his first consulship and, with his consular colleague, Cn. Cornelius Scipio Calvus, presided over the closing stages of a war in the Po valley that had begun with a Gallic invasion of Roman territory in 225 BC.

Events in Cisalpine Gaul in 222 BC

By 222 BC, the Gauls were essentially contained to the north of the Po, but the threat from the Gallic Insubres remained real. Initially, both consuls laid siege to the Insubrian stronghold of Acerrae. However, when the Insubrians created a diversion by attacking their allies at nearby Clastidium (modern Casteggio, some 60 km south of Milan), Marcellus led a small force of cavalry and light infantry to address the new threat, and it was during this engagement that he secured his triumph and the right to dedicate the spolia opima to to Jupiter Feretrius.

Gareth Sampson (referenced below, at pp. 166-72) gave a detailed account of the surviving sources for this engagement, which range from:

✴the glowing (Plutarch);

“[Marcellus] left his colleague at Acerrae with all the heavy-armed infantry and a third of the cavalry, while he led rest of the cavalry and the most lightly equipped men-at‑arms ... against the 10,000 Gaesatae [Gallic mercenaries] near the place called Clastidium ... [The Gaesatae], who quickly learned of [Marcellus’ arrival at Clastidium]:

✴held [Marcellus small force of] infantry in contempt ... ; and

✴discounted his cavalry, [since] they themselves were excellent fighters on horseback and far outnumbered it].

Immediately, therefore, they charged ... , their king riding in front of them. Marcellus [manoeuvred in order to avoid being surrounded] but, just as he was turning to charge, his horse took fright ... [He] quickly [regained control] of his horse ... , while making adoration to the sun, implying that it was ... for this purpose that he had wheeled about. ... [Then], as he engaged with the enemy, he is said to have vowed that he would consecrate to Jupiter Feretrius the most beautiful suit of armour among them. Meanwhile the king of the [Gaesatae], judging from his insignia that Marcellus was in command, rode far out in front of [his own cavalry] ..., shouting challenges and brandishing his spear. He was ... was conspicuous for his armour, which was decorated with gold and silver ... and gleamed like lightning. Marcellus ... [therefore] concluded that this was the armour that he had vowed to the god. He therefore rushed upon the man, pierced his breastplate with his spear and unhorsed him, killing him with a second and third blow as he lay on the ground. ... Then, leaping from his horse and seizing the armour of the dead man, he looked towards heaven and said:

‘O Jupiter Feretrius, who has witnessed the great deeds and exploits of generals and commanders in war, I call you [now] to witness that:

✴I have ... killed this man with my own hand, and I am now the third Roman ruler and general to kill [an enemy] ruler and king in this way; and

✴I now dedicate to you [his armour as] the first and most beautiful of the spoils.

I therefore beseech you to grant [the Romans] similar good fortune as we prosecute the rest of the war.’

His prayer ended, the cavalry joined battle, fighting not only with the enemy's horsemen but also with their infantry and won a remarkable and strange victory: for, we are told that, never before or since, have so few horsemen conquered so many horsemen and infantrymen together. After killing the greater part of the enemy and seizing their arms and baggage, Marcellus returned to his colleague [who was, by then at the Insubrian capital at at Mediolanum (modern Milan)] ... ,”, (‘Life of Marcellus’, 6:4 - 7:4): to

✴the mundane (Polybius, ca. 150 BC):

“[When the Romans learned of the Gallic attack at Clastidium, Marcellus] set off in haste with the cavalry and a small body of infantry to relieve the besieged if possible. As soon as the [Gauls] became aware of the enemy’s arrival, they raised the siege ... [marched against them] in battle order. When the Romans boldly charged them with their cavalry alone, they first stood firm, but afterwards ... found themselves in difficulties. They were finally put to flight by the cavalry unaided: many of them threw themselves into the river and being swept away by the current, while even more of them were cut to pieces by the enemy. ... The Romans now took Acerrae ...” , (‘Histories’, 2: 34: 6-9)

As Frank Walbank (referenced below, at p. 211) observed:

“It may be deliberately that Polybius omits the gaining of spolia opima by Marcellus in his duel with the Insubrian chieftain ...”

The most objective of the surviving accounts of Marcellus’ victory is probably that of the military strategist, Frontinus: in a chapter on military commanders who benefitted from an innate determination to win, he included:

“Claudius Marcellus, [who], having unexpectedly come upon some Gallic troops, turned his horse about in a circle, looking around for a way of escape. Seeing danger in every direction, with a prayer to the gods, he broke into the midst of the enemy. By his amazing audacity, he threw them into consternation, killed their leader, and carried away the spolia opima, [having initially found himself] in a situation in which there had been little hope of even saving his own life”, (‘Strategems’, 4: 5: 4).

Polybius and Plutarch also gave very different accounts of the subsequent Roman victory over the Insubres:

✴Polybius made no further mention of Marcellus: after the victory at Clastidium:

“The Romans now took Acerrae ... [and] the Gauls withdrew to Mediolanum, the chief place in the territory of the Insubres. [Scipio] followed close on their heels, and suddenly appeared before Mediolanum. The Gauls did not react when he arrived but, when he was on his way back to Acerrae, they ... attacked from the rear, ...[Scipio managed to regroup, and the Gauls] were shortly put to flight, taking refuge on the mountains. ... [Scipio then] took Mediolanum by assault, at which point, the leaders of the Insubres ... put themselves entirely at the mercy of the Romans , (‘Histories’, 2: 34: 10-15).

✴On the other hand, according to Plutarch, after his victory at Clastidium:

“Marcellus returned to his colleague, who was under pressure in his war with the Gauls near ... Mediolanum. ... The Gauls considered [this city] to be their metropolis and consequently defended it so effectively that [Scipio] was less besieger than besieged. However, when:

•Marcellus arrived; and

•the Gaesatae [there] withderw after learning of the defeat and death of their king[at Clastidium].

Mediolanum was taken, [at which point], the [Insubres] surrendered the rest of their cities and put themselves entirely at the disposition of the Romans. They obtained peace on equitable terms”, (‘Life of Marcellus’, 7: 4-5).

There were obviously competing traditions at play here, and Polybius clearly relied on a tradition that was particularly favourable to Cn. Cornelius Scipio Calvus (perhaps in deference to his own patron, P. Cornelius Scipio Africanus Aemilianus, the adoptive grandson of Scipio Africanus). As Gareth Sampson (referenced below, at pp. 174-5) observed:

“If there was a significant Gaesatae contingent still defending [Mediolanum], then reports of the destruction of their army and the death of their chieftain [at Clastidium might well have been] the final straw for them ... ; and, if the Gaesatae once again deserted their Gallic allies, ... [this] might well have been] the final straw for the Insubres, [leaving them with no option but to surrender] their capital.”

In other words, however lucky Marcellus had been when he had killed the Gallic chieftain at Clastidium, the ‘amazing audacity’ that he had displayed on this occasion might well have been the most important factor in the Romans’ subsequent definitive victory over the Insubres.

Marcellus’ Triumph and Dedication of the Spolia Opima

Unfortunately, Livy’s Book 20, which described Marcellus’ command in Cisalpine Gaul in this year, no longer survives, although we know from the surviving summary that contained the information that:

“The consul M. Claudius Marcellus killed the leader of the Gallic Insubres, Vertomarus, and returned [to Rome] with the spolia opima”, (‘Perioche’, 20: 11).

The unusually long and informative entry in the Augustan fasti Triumphales for this year (which is discussed further below) recorded that:

“M. Claudius M.f. M.n. Marcellus, proconsul (sic), [triumphed] over the Insubrian Gauls and the Germans on the 1st March: he brought back the spolia opima after killing the enemy leader, Virdumarus, at Clastidium”.

According to Plutarch, on the consuls’ return to Rome:

“The Senate decreed a triumph to Marcellus alone, and his triumphal procession was seldom equalled in its splendour and wealth ... , [and] the most agreeable and the rarest spectacle of all was afforded when Marcellus himself carried to the god the armour of the barbarian king. He had cut the trunk of a slender oak, straight and tall, and fashioned it into the shape of a trophy; on this he bound and fastened the spoils, arranging and adjusting each piece in due order. When the procession began to move, he took the trophy himself and mounted the chariot, and thus a trophy-bearing figure, more conspicuous and beautiful than any other of his day, passed in triumph through the city. The army followed, wearing the most beautiful armour, singing odes composed for the occasion, together with paeans of victory in praise of the god and their general. Thus advancing and entering the temple of Jupiter Feretrius, Marcellus set up and consecrated his offering, being the third and last to do so, down to our time:

✴the first was Romulus, who despoiled Acron the Caeninensian;

✴the second was [A.] Cornelius Cossus, who despoiled Tolumnius the Etruscan;

✴and after them Marcellus, who despoiled Britomartus, king of the Gauls;

but after Marcellus, no man”, (‘Life of Marcellus’, 8: 1-3).

Naevius and the Events at Clastidium

Marcellus’ exploits at Clastidium seem to have quickly seized the public imagination: as Eric Warmington (referenced below, at p. xv) observed, the poet Cn. Naevius, who had been producing plays in Rome since ca. 235 BC:

“... invented a new kind of play, the fabula praetexta or historical Roman play, by composing one (‘Clastidium’) that dealt with the victory won at Clastidium by M. Marcellus in 222 BC; another one, ‘Romulus’, perhaps followed soon afterwards.”

Both of these plays are lost, but Varro (‘On the Latin Language’, 9: 78) referred to:

“... a passage of Naevius’ ‘Clastidium’:

‘Back to his native land, happy in life, never dying’”, (translated by Eric Warmington, referenced below, at 137).

Sander Goldberg (referenced below, at p. 32) pointed out that this line suggests a victorious general who had safely returned home.

Harriet Flower (referenced below, 1995, at p. 184) suggested that ‘Clastidium’ might well have been first performed at the instigation of Marcellus’ homonymous son when he dedicated the temple of Honus and Virtus in 205 BC, after his father’s death. She observed that this would have been:

“... a good time to recall the famous victory and to try to rehabilitate Marcellus’ earlier career once the memory of his [ignominious] death [in an ambush laid by Hannibal] had faded.”

It seems likely that Naevius’ stage version of the Battle of Clastidium heavily influenced the narrative accounts of later authors. This might, for example, account for the theatrical tenor of Plutarch’s account of Marcellus’ duel with the Gallic chieftain and his subsequent dedication of the spolia opima at the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius.

Denarius of [P ?] Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus

Denarius (RRC 439/1) issued in Rome, probably issued by [P] Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus in ca. 50 BC

Obverse: MARCELLINVS; head of M. Claudius Marcellus (with triskele behind, for his capture of Syracuse)

Reverse: MARCELLVS COS·QVINQ (for his five consulships):

Marcellus carries the spolia opima (which he won in 222 BC) into the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius

Our earliest surviving evidence for Marcellus’ dedication of the spolia opima is found on the reverse of the denarius described at the top of this page. Kamil Kopij (referenced below, at p. 176) pointed out that the evidence from coin hoard indicates that is was issued before about 50 BC. He also observed that moneyer’s agnomen Marcellinus places him a branch of the Cornelii Lentuli that had started with the adoption by a member of this gens of a member of the gens Claudia Marcella. This points to a passage in which Cicero referred to the orator:

“M. Marcellus, the father of Aeserninus: although [he was] not recognised as a professed pleader, was a prompt and, in some degree, a practised speaker, like his son, P. Lentulus”, (‘Brutus: A History of Famous Orators’, 136).

The three men mentioned in this passage were:

✴M. Claudius Marcellus (pr before 102 BC); and

✴his sons:

•M. Claudius Marcellus Aeserninus; and

•P. Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus, the moneyer who identified himself as LENT MAR F on the denarius (RRC 329/1) that he issued in 100 BC, after his adoption into the gens Cornelia Lentuli. (Interestingly, the triskele is depicted on the reverse of the as (RRC 329/ 2) in this series.

Michael Crawford (referenced below, at p. 460) observed that the moneyer of the coins under discussion here:

“... is presumably P. Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus, quaestor [under Julius Caesar] in 48 BC.”

Caesar referred to this man on two occasions

Caesar recorded that, when the news of the fall of Auximum reached Rome:

“... the panic that suddenly hit [the City] was so great that, although the consul Lentulus had come to open the treasury to provide money for Pompey in accordance with the Senate’s decree [of 17th January - above], he fled the city directly after opening the treasury reserve, because false reports [had it that] Caesar was already approaching ... Lentulus was followed by his colleague Marcellus and most of the magistrates”, (‘Civil War’, 1: 14: 1-3), translated by Cynthia Damon, referenced below, at p. 23).

Marcellus’ exploits on this occasion gained even more significance at the time of the Emperor Augustus: thus, for example, John Rich (referenced below, at p. 240) argued that:

“It was surely by design that the second pilaster of the inscribed [Augustan fasti Triumphales] (and so the first half of the list) ended with the extended entry for the first triumph of M. Claudius Marcellus, with its additional sentence recording his spolia opima. By the mid-20s BC, Augustus was planning the rapid advancement of his nephew, Marcellus’ descendant and namesake. If the inscription was originally designed and set up ... at that time, a few lines may have been deliberately left vacant (at the end of the list] in the expectation that the new Marcellus would provide a fitting climax to the fourth pilaster. If so, such hopes were dashed by the youth’s untimely death in 23 BC, leaving the vacant spaces to be filled by Atratinus and Balbus.

John Rich (referenced below, at p. 220) characterised this as:

“... a notable revival of a practice of hoary antiquity when Marcellus, having personally killed the Gallic king Virdumarus, claimed the right to dedicate his victims’ weaponry to Jupiter Feretrius as spolia opima ... [He was] only the third [man in Roman tradition, after Romulus and A. Cornelius Cossus] to do so, and was probably the first to combine such a dedication with a chariot triumph. ... his achievement is accorded the longest entry in the [surviving parts of the fasti Triumphales ... ].”

This great achievement was also celebrated by at least two of the leading Augustan poets

✴Virgil wrote that Marcellus:

“... advances, graced with the spolia opima: [see] how he towers in victory over all men! When the Roman State is reeling under a brutal shock, he will steady it: he will ride down [both] Carthaginians and the insurgent Gauls, and tertiaque arma patri suspendet capta Quirino (will hang up the third set of captured arms to Quirinus)”, (‘Aeneid’, 6: 854-9, translated by Henry Rushton Fairclough, referenced below, at pp. 593-5).

✴Propertius, in his elegy on the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius, recorded that:

“Now shall I begin to tell the origins of Jupiter Feretrius and the three sets of arms he won from three duces (commanders). ... [The first two commanders were Romulus and A. Cornelius Cossus, and the third was Marcellus, who] beat back the giant chief, Virdomarus after he had crossed the Rhine, boasting descent from Brennus himself. Marcellus brought [Virdomarus’] Belgic shield of back to Rome, ... [together with] the twisted necklace that fell, as a prize, from his severed throat. Now, three [sets of spolia opima] are preserved in the temple, [which is] why it is called Feretrius:

•because dux ‘ferit’ ense ducem (commander struck commander with a sword) ...; or

•perhaps because [the three victorious Roman commanders] ferebant (carried) the captured arms on their shoulders ...”, (‘Elegies’, 4: 10: 1-45, translated by George Goold, referenced below at pp. 377-81, word order changed).

The first part of the entry for by the Augustan antiquarian M. Verrius Flaccus in his now-lost lexicon was summarised by Festus as follow:

“... quae dux populi Romani duci hostium detraxit; quorum tanta raritas est, ut intra annos paulo [lacuna of 19 letters] ... trina contigerint nomini Romano:

✴una, quae Romulus de Acrone;

✴altera, quae Cossus Cornelius de Tolumnio;

✴tertia, quae Marcus Marcellus [lacuna] Viridomaro, fixerunt”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 202 L: 35-6 and 204 L: 1-4, , see Alessia Di Marco, referenced below, at pp. 174-6)

“... those that a Roman commander took from an enemy commander. These were of such rarity [difficult to translate because of the lacuna, presumably saying that only three sets of such spoils were won in Rome over a long period]:

✴... first, those that Romulus [took] from Acron, [king of Caenina];

✴another, those that ... Cossus Cornelius [took] from Tolumnius; and

✴third, those that M. Marcellus [took] from Viridomarus [and] set up [in the shrine of] Jupiter Feretrius ?]”, (my translation).

Florus:

“During the reign of Viridomarus, [the Gauls] had promised to offer up Roman armour to Vulcan; but their vows turned out otherwise, for their king was killed and Marcellus hung up in the temple of Jupiter Feretrius the spolia opima for the second time since father Romulus had done so”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 1: 20: 5)

YaL Max. 3.2.5;

Plut., Marc. 7-8, Comp. Pelop. Marc. 1.2, and Rom. 16.7-8;

Read more:

Sampson G., “Rome Spreads Her Wings: Territorial Expansion Between the Punic Wars”, (2016) Barnsley

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Vol. II: Books VII and VIII”, (1998) Oxford

Flower H., “Fabulae Praetextae in Context: When Were Plays on Contemporary Subjects Performed in Republican Rome?”, Classical Quarterly, 45:1 (1995) 170-90

Goldberg S., “Epic in Republican Rome”, (1995) New York and Oxford

Crawford M., “Roman Republican Coinage”, (1974) Cambridge

Walbank F. “A Historical Commentary on Polybius’: Vol. 1, Books 1-6”, (1957) Oxford

Warmington E. (translator), “Livius Andronicus, Naevius, Pacuvius, Accius: Remains of Old Latin, Volume II: Livius Andronicus; Naevius; Pacuvius; Accius”, (1936) Cambridge MA

Di Marco A., “Per la Nuova Edizione del De Verborum Significatione di Sesto Pompeo Festo: Tradizione Manoscritta e Specimen di Testo Critico (Lettera O)”, (2017/8) thesis of the Università degli Studi Roma Tre

Rich J., “The Triumph in the Roman Republic: Frequency, Fluctuation and Policy”, in:

Lange C. and Vervaet J. (editors), “The Roman Republican Triumph: Beyond the Spectacle”, (2014) Rome, at pp. 197-258

Kopij K, “Propaganda War over Sicily?: Sicily in the Roman Coinage During the Civil War (49-45 BC)”, Studies in Ancient Art and Civilization, 12 (2012) 167-8282

Rushton Fairclough H. (translator), “Virgil: Eclogues. Georgics. Aeneid: Books 1-6.”, (1916) Cambridge MA

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)