Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Romulus and the Spolia Opima

Linked Pages: Spolia Opima;

Romulus and the Spolia Opima; A. Cornelius Cossa and the Spolia Opima (437, 428 or 426 BC);

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Romulus and the Spolia Opima

Linked Pages: Spolia Opima;

Romulus and the Spolia Opima; A. Cornelius Cossa and the Spolia Opima (437, 428 or 426 BC);

Copy of a fresco of Romulus on the facade of the house of Fabius Ululitremulus on Via dell’ Abbondanza at Pompeii

From the website Pompeii in Pictures

An inscription (CIL X 0809, ca. 70 AD) from a statue base in Pompeii can be translated as follows:

“Romulus, the son of Mars, founded the city of Rome and reigned for 38 years. He was the first dux (commander) who, having killed Acron, king of Caenina, duce hostium (the enemy commander), consecrated spolia opima to Jupiter Feretrius. After being received among the gods, he was called Quirinus”, (based on the translation by Alison and M.G. L. Cooley, referenced below, at p. 142).

They also translated the inscription for a matching statue base that related to a statue of Aeneas, and observed (at p. 140) that the associated statues had almost certainly:

“... imitated monuments at Rome: namely the statues set up in the of Augustus [in or before 2 BC]. The iconography of these [Roman] statues was apparently familiar at Pompeii, appearing in paintings on the Street of Abundance.”

The illustration above is a copy of the painting of Romulus there. John Rich (referenced below, 1998, at pp. 94-5) argued that:

“Whereas the other statues in the Forum Augustus were merely standing figures, those of Aeneas and Romulus depicted their subjects in action. ... Romulus was portrayed as the winner of the spolia opima, holding a spear in his right hand and carrying on his left shoulder the spolia opima in the form of a trophy. The Pompeii copy [translated above] shows that the elogium of Romulus [in the Forum Augustum] gave special prominence to his winning of the spolia opima.”

Thus, is seems that the tradition of Romulus‘ dedication of the first spolia opima after his victory over Caenina assumed a monumental reality at the heart of Augustan Rome at the end of the 1st century BC.

Romulus’ Victory over Caenina

Livy

Livy (ca. 28 BC), who wrote the earliest surviving narrative account of Romulus’ war with Caenina, characterised it as a direct result of his famous abduction of the so-called Sabine women: apparently some of these women had come from the Latin settlement of Caenina, and, as the other affected communities procrastinated, the men of Caenina:

“... unilaterally invaded Roman territory. Romulus encountered them with his army as they were scattered and engaged in plundering and, in a quick fight, taught them the futility of anger without strength. He routed their army, ... killed their king in battle and despoiled him [of his armour]”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 10: 3-4).

After this victory:

“... exercitu victore reducto (the victor led back the army) [to Rome]. Magnificent in action, he was no less eager to publicise his achievements. So, he hung the spoils of the enemy commander that he had killed on a frame made to fit the purpose, and went up to the Capitol, carrying it himself”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 10: 5).

This is the scene that was represented in the fresco at Pompeii that illustrated above, which, as we have seen, was almost certainly inspired by the now-lost statue of Romulus that was unveiled in the Forum Augustum in 2 BC. Frances Hickson Hahn (referenced below, at p. 95) pointed out that Livy’s account of Romulus’ return to Rome:

“... contains the primary features found in later triumph notices:

✴the return of the army;

✴the procession with the commander; and

✴the display of the captured spoils.”

Be that as it may, Livy seems to have believed that the Roman triumph was instituted much later in the Regal period: as Miriam Pelikan Pittenger (referenced below, at p. 33, note 2) pointed out, his first use of the word triumphans came in the following passage:

“After bringing the Sabine war to a conclusion, Tarquinius Priscus, [traditionally the 5th king of Rome], triumphans Romam redit (returned to Rome in triumph)”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 38: 3).

According to Livy, when Romulus reached the Capitol:

“He set [the spoils] down by an oak tree that was sacred to the shepherds and, at the same time as he made his offering, he marked out the boundary of a temple to Jupiter and gave the god an additional title, declaring:

‘To you, Jupiter Feretrius, I, Romulus, victor and king, bring spoils taken from a king. On the site that I have just marked out in my mind, I dedicate a precinct to be a place for the spolia opima that men of the future, following my example, will bring to this place when they have killed regibus ducibusque hostium (kings and commanders of our enemies).’

This was the origin of the first templum that was consecrated in Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 10: 5-7).

Thus, for Livy, the most important things about Romulus’ victory over Caenina were that Romulus:

✴characterised the armour that he had stripped from the king of Caenina as spolia opima; and

✴dedicated these spoils to Jupiter:

•in a new form, Jupiter Feretrius, and

•at a new cult site on the Capitol, which was the first Roman templum.

Furthermore, Romulus intended that any future Roman commander who emulated him by killing an enemy king or commander in single combat should also emulate him by dedicating the dead man’s armour as spolia opima to Jupiter Feretrius at this site on the Capital.

Fasti Triumphalis

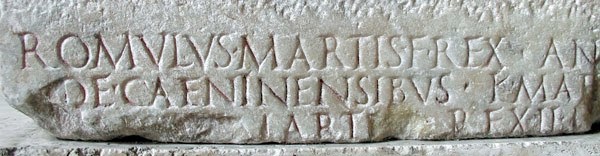

Opening lines of the fasti Triumphales (now in the Musei Capitolini)

From ‘Mr Jennings’ on Flickr

In or shortly after 19 BC, the marble tablets inscribed with the so-called fasti Triumphales were set into the walls of an arch in the Forum Romanum, almost certainly at the behest of the Emperor Augustus. As Denis Feeney (referenced below, at p. 181) observed, the first two lines of the inscription read:

Romulus Martis F Rex Ann ... / De Caeninensibus K Mar

(Romulus, son of Mars, King, in Year I, [triumphed] over the Caeninenses on 1st March)

Feeney stressed that:

“In an unbeatably primal moment, Romulus is celebrating the first Roman triumph on Day 1, Year 1 of [the existence of the city of] Rome and, from then on, every one of the triumphs [recorded in the fasti] has the year from the foundation of the city recorded ... .”

Thus, about 17 years before the unveiling of the statue of Romulus carrying the spolia opima in the Forum Augustum, Augustus officially:

✴proclaimed that Romulus had triumphed over Caenina; and

✴equated the year of his triumph with the year in which Rome had been founded.

However, as John Rich (referenced below, 2014, at p. 201, note 19) pointed out:

“Although the list’s entry for ... [the] triumph [of M. Claudius Marcellus - see below] in 222 BC gives ample space to his spolia opima, there is no mention of Romulus’ spolia opima in its opening entry for his first triumph.”

This is clear because the fragmentary third line of the inscription refers to Romulus’ second triumph.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius (who arrived in Rome in 30/29 BC and published his ‘Roman Antiquities’ in 7 BC) also recorded that the men of Caenina were the first to attack the Romans after the abduction of the ‘Sabine‘ women:

“When these men ... were devastating [Roman territory], Romulus led out his army, ... [unexpectedly attacked them] ... and captured their camp ... Then, he followed close upon the heels of those enemy soldiers that fled to Caenina ... [and, finding] the walls unguarded and the gates unbarred, he took the town by storm. When the king of Caenina met him with a strong body of men, he ... killed him with his own hands and stripped him of his arms”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 33: 2).

In Dionysius’ account, Romulus then secured a quick victory at Antemnae, after which, he:

“... led his army home, carrying with him he spoils of those whom had been killed in battle and the choicest part of the booty as an offering to the gods; ... Romulus himself came last in the procession, clad in a purple robe and wearing a crown of laurel upon his head. So that he might maintain the royal dignity, he rode in a chariot drawn by four horses. The rest of the army ... followed, ... praising the gods in songs of their country and extolling their general in improvised verses. ... When the army entered the City, they found that mixing bowls filled to the brim with wine and tables loaded down with all sorts of food were placed before the most distinguished houses, in order that all who pleased might take their fill. Thus, the victory procession, as it was first instituted by Romulus, which the Romans call a triumph, was marked by the carrying of trophies and concluded with a sacrifice”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 34: 1-3).

Thus, for Dionysius, the most important thing about Romulus’ putative back-to-back victories over Caenina and Antemnae was that his subsequent return to Rome, which was:

“... marked by the carrying of trophies and concluded with a sacrifice “,

constituted the first Roman triumph. Interestingly, Dionysius’ fellow-Greek, Plutarch (who visited Rome in ca. 70 AD) emphatically claimed that:

“... Dionysius is incorrect in saying that Romulus used a chariot [in his triumphal procession]: for, it is matter of history that Tarquin, the son of Demaratus, [i.e. , . Tarquinius Priscus], was first of the kings to lift triumphs up to such pomp and ceremony (and indeed, others say that Publicola, [i.e., P. Valerius Poplicola, who traditionally triumphed in 504 BC], was first to celebrate a triumph riding on a chariot). [Furthermore], all the statues of Romulus bearing the trophies that can be seen in Rome [portray him] on foot”, (‘Life of Romulus’, 16: 8).

Gavin Weaire (referenced below, at pp. 109-10) suggested that:

“Plutarch’s account may, in fact, have been his own creation, inspired by artistic images of the tropaiophoric (trophy-bearing) Romulus.”

Weaire also noted (at p. 116, with references at note 34) that the most famous image of this kind stood in the Forum Augustum (as discussed above).

Dionysius devoted relatively few words to the events that followed:

“After [this triumphal] procession and the sacrifice, Romulus built a small temple to Jupiter, whom the Romans call Feretrius, on the summit of the Capitol; indeed, the ancient traces of it still remain, of which the longest sides are less than 15 feet. In this temple, he consecrated the [armour] of the king of Caenina, whom he had killed with his own hands”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 34: 4).

Interestingly, it seems that Dionysius had actually visited the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius, presumably during or after its restoration in ca. 30 BC (see below). It is therefore particularly surprising that, although he:

✴recorded that Romulus had built the temple and dedicated the armour of the king of Caenina there; and

✴mentioned on two occasions that Romulus had killed this king with his own hands;

he did not designate this armour as the spolia opima and did not differentiate it from the other trophies that had featured in what he had characterised as the first triumphal procession.

Read more:

Hickson Hahn F., “Livy's Liturgical Order: Systematisation in the History”, in:

Mineo B. (editor), “A Companion to Livy”, (2015) Chichester

Cooley A. and M. G. L., “Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook”, (2014 ) London

Rich J. W., “The Triumph in the Roman Republic: Frequency, Fluctuation and Policy”, in:

Lange C. J. and Vervaet F. (editors), “The Roman Republican Triumph: Beyond the Spectacle”, (2014 ) Rome, at pp. 197-258

Weaire G. , “Plutarch versus Dionysius on the First Triumph”, Ploutarchos, 7 (2010) 107-24

Feeney D., “Caesar's Calendar Ancient Time and the Beginnings of History”, (2008) Berkeley

Pelikan Pittenger M., “Contested Triumphs: Politics, Pageantry and Performance in Livy's Republican Rome”, (2008) Berkeley, Los Angeles and London

Rich J. W., “Augustus's Parthian Honours, the Temple of Mars Ultor and the Arch in the Forum Romanum”, Papers of the British School at Rome, 66 (1998) 71 - 128

Coarelli F., (translated into English by J. Clauss and D. Harman), “Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide”, (2014) Oakland, CA

Koortbojian M., “The Divinisation of Caesar and Augustus: Precedents, Consequences, Implications”, (2013) New York

Ver Eecke M., “La République et le Roi: le Mythe de Romulus à la Fin de la République Romaine”, (2008) Paris

Forsythe G., “Critical History of Early Rome”, (2005) Berkelely, Los Angeles and London

Holliday P. J., “The Rhetoric of "Romanitas: The ‘Tomb of the Statilii’ Frescoes Reconsidered”, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 50 (2005) 89-129

Fishwick D., ‘‘The Name of the Demigod,’’ Historia, 24 (1975) 624–8

Weinstock S., “Divus Julius”, (1971) Oxford

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)