Events of 216 BC

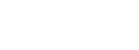

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Battle of Cannae

In March 216 BC, the new consuls, L. Aemilius Paullus and C. Terentius Varro, began the task of assembling a huge army that would, it was hoped, drive Hannibal from Italy. Meanwhile, the commands of M. Atilius Regulus and Cn. Servilius Geminus were prorogued. According to John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 76), probably in June 216 BC, Hannibal marched some 95 km to the south and captured the Roman supply depot at the small town of Cannae, which had probably belonged to the nearby city of Canusium. Servilius and Atilius followed him from Larinum, and met up with the consular armies, which were en route from Rome. According to Livy (22: 40: 6), Atilius was allowed to return to Rome on account of his age, while Servilius remained with the army. After a two-day march, the combined Roman armies arrived at Cannae at the end of July. As John Lazenby observed (at p. 77):

-

“The scene was set for the greatest land battle yet fought between Rome and Carthage.”

It was also set for the most shattering defeat in Roman history: Lazenby estimated (at p. 84) that some 50,000 Romans (including both Aemilius and Servilius) died and some 20,000 were taken prisoner. Varro, the surviving consul, now had an army of fewer than 15,000 men sheltering in the safety of the colony at Venusia, many of whom had survived because of help from Canusium. In short, Verrucosus’ decision to avoid direct engagement with Hannibal in 216 BC had been vindicated in the most spectacular fashion.

Defections after Cannae

John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 86) argued that, despite his victory at Cannae, Hannibal was not in a position to march on Rome without the help of disaffected allies who might desert Rome:

-

“Thus, for Hannibal, Cannae must have seemed, not so much the end of the war, ... as the beginning of the end: his ... original strategy [of winning Italian allies whenever possible was to be vindicated when] much of southern Italy now began to come over to him.”

As Livy observed:

-

“... the extent to which this disaster exceeded all those that had gone before is plain from this: that the loyalty of the allies, who had held firm until the day of Cannae, now began to waver: ... these are the peoples that revolted:

-

✴the Campanians, [including] the Atellani, [and] the Calatini;

-

✴... a part of the Apulians;

-

✴all of the Samnites, including the Hirpini [although not] the Pentri;

-

✴the Bruttii;

-

✴the Lucanians;

-

✴... the Uzentini;

-

✴almost all the Greeks on the coast:

-

•the Tarentines;

-

•the Metapontines;

-

•the Crotoniates; and

-

•the Locri; and

-

✴all the Cisalpine Gauls”, (‘Roman History’, 22: 61: 10-12).

In fact, not all of these defections took place in 216 BC: however, Livy is certainly correct that Hannibal enjoyed the support of most of Campania in the period 216-211 BC, and most of the rest of southern Italy until 203 BC.

Reaction at Rome

Varro decided to move his base of operations from Venusia to Canusium, a large city that was probably more likely to withstand a direct attack by Hannibal. He then sent details of the precise military situation to Rome, at which point:

-

“.. the Senate voted to:

-

✴send M.Claudius Marcellus, the praetor commanding the fleet at Ostia, to Canusium; and

-

✴write to [Varro], instructing him to turn his army over to Marcellus and return to Rome at the earliest moment compatible with the welfare of the state”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 57: 6-7).

Having sent reinforcements from Ostia to Rome, Marcellus duly hastened, as ordered, to Canusium. John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 91) suggested that Varro had actually been summoned to Rome to appoint Junius as as dictator, following which, he might well have relieved Marcellus at Canusium (see below).

Meanwhile, at Rome:

-

“The Senate authorised the appointment of M. Junius Pera as dictator, with Ti. Sempronius Gracchus as master of the horse. Proclaiming a levy, they enlisted the young men over 17 and some who still wore the purple-bordered dress of boyhood. ... They also sent men to the allies and the Latins to take over their soldiers, as by treaty provided”, (‘‘History of Rome’’, 22: 57: 8-9).

When Hannibal sent an envoy to Rome:

-

“... a lictor was sent to intercept him and warn him, in the name of the dictator, to leave Roman territory before nightfall”, (‘‘History of Rome’’, 22: 58: 9).

The Senate also turned its face against paying a ransom to secure the release of Roman prisoners of war.

Manoeuvres in Campania

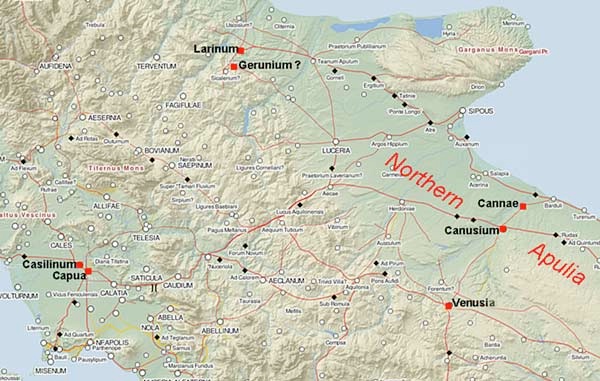

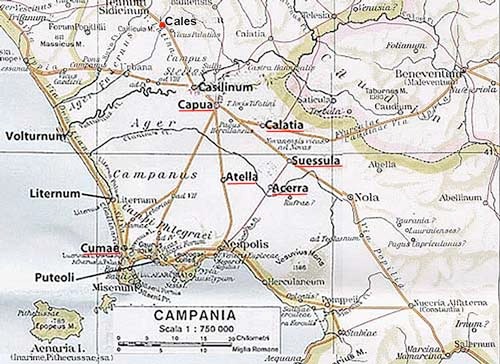

Campanian cities with civitas sine suffragio (underlined in red)

Red dot = Latin colony of Cales

Adapted from this map on the webpage on Roman Campania by Jeff Matthews

The defections of Capua, Atella and Calatia noted above would have been particularly dangerous, given the fact that the inhabitants here were Roman citizens: Capua was of particular importance, since both the Via Latina and the Via Appia linked it directly to Rome. Fortunately, Fabius had established a garrison in 216 BC at nearby Casilinum, which occupied a strategic position at the junction of the Via Latina and the Via Appia, on the site of the bridge over the Vollturnus. Furthermore, the town was still occupied by a small body of Roman troops (consisting principally of Latins from Praeneste, and Etruscans from Perusia), that had been en route for Cannae at the time of the battle there. Marcellus established a base here, probably after he had been relieved at Canusium on Varro’s return there (see above).

John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 92) described the manoeuvres in Campania. Having made his triumphant entry into Capua, Hannibal marched south and attacked the city of Nola, and Marcellus marched to its defence. Hannibal seems to have offered little resistance, choosing instead to withdraw and try his luck (unsuccessfully, as it turned out) at Neapolis. He drove the people of Nuceria from their city, which he destroyed and then tried again at Nola, where Marcellus seems to have driven him off. Livy commented that:

-

“I would hardly venture to assert (as some authorities do) that 2,800 of the enemy were killed [during the engagement at Nola] while the Romans lost no more than 500. But, [whatever the scale of the victory], I doubt that a more important battle was fought during the whole war ...”, (‘‘History of Rome’’, 23: 16: 15).

Hannibal then destroyed Acerra and attacked Casalinum, but the garrison there repelled him, so he retired to winter quarters at Capua.

However, he returned to Casalinum early in the following year and laid siege to the city. At this time:

-

✴the dictator M. Junius Pera, who was camped outside the city, had apparently returned to Rome leaving orders that his master of horse, Ti. Sempronius Gracchus, should not engage with Hannibal in his absence; and

-

✴Marcellus, who had established a base at Suessula, was unable to cross the flooded Volturnus in order to raise the siege.

The Roman garrison at Casilinum was thus faced starvation and was forced to surrender. According to Livy, Hannibal allowed the survivors to be ransomed, and those from Praeneste:

-

“... returned [there] in safety. ... with their commanding officer, M. Anicius, who had formerly been a notary”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 19: 17).

It seems that the Romans were extremely appreciative of the efforts of their Praenestine allies: according to Livy:

-

“The Senate decreed that the Praenestine troops should be granted double pay and an exemption for five years from further service. They were also offered the full Roman citizenship, but they preferred not to change their status as citizens of Praeneste”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 20: 2).

Michael Fronda (referenced below, at p. 243) observed that:

-

“With [Hannibal’s] capture of Casilinum in [early] 215 BC, the battle lines in Campania were drawn: Hannibal controlled Capua and its subordinate allies [Atella, Calatia and now Casilinum]: Rome held the remaining cities in the region, and all of Italy looked on.”

Events in Italy (215 - 214 BC)

Events of 215 BC

Livy recorded that, towards the end of the consular year:

-

“... the Senate ... [wrote] to the dictator [M. Junius Pera], asking him ... to come to Rome to conduct the election of fresh consuls. He was to bring with him his master of the horse and M. Marcellus, the praetor, so that the Senate might learn from them on the spot in what condition the affairs of the Republic were, and form their plans accordingly. On receiving the summons, they all came, after leaving officers in command of the legions. The dictator ... then gave notice of the elections. The consuls elected were

-

✴L. Postumius Albinus for the 3rd time (who was elected in his absence, as he was then administering the province of Gaul); and

-

✴and Ti. Sempronius Gracchus, [then] master of the horse and also a curule aedile.

-

After [these and the other] magistrates had been elected, the dictator returned to his army in winter quarters at Teanum. [Gracchus] was left in Rome; as he would be entering upon office in a few days, it was desirable for him to consult the Senate about the enrolment and equipment of the armies for the year”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 24: 1-5).

Disaster in Gaul

Even before the new consular year had started:

-

“... a fresh disaster was announced, for Fortune was heaping one disaster upon another this year. It was reported that L. Postumius Albinus, the consul elect, and his army had been annihilated [at Mutina] in [Cisalpine] Gaul. ... Hardly ten men escaped ... : Postumius fell whilst fighting most desperately to avoid capture. The Boii stripped the body of its spoils, cut off the head, and bore them in triumph to the most sacred of their temples. According to their custom, they cleaned out the skull and covered the scalp with beaten gold; it was then used as a vessel for libations and also as a drinking cup for the priest and ministers of the temple. The plunder that the Gauls secured was as great as their victory ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 24: 6-13).

As Stephen Dyson (referenced below, at p. 14) observed:

-

“The Romans, their resources strained by recent disasters, were [manifestly] unable to respond to this defeat. The level of [their] control in the area during this crucial phase of the Second Punic War must have been minimal.”

Livy recorded that, when the news from Cisalpine Gaul reached Rome, it led to public hysteria that was only calmed when Gracchus:

-

“ ... convened the Senate and addressed them in a consolatory and encouraging tone, [saying]:

-

‘We, who were not crushed by the overthrow at Cannae, must not lose heart at smaller calamities [like that at Mutina]. If we are successful in our operations against Hannibal and the Carthaginians, as I trust we shall be, we can safely leave the war with the Gauls out of account for the present; the gods and the Roman people will have it in their power to avenge that act of treachery [after Hannibal is defeated]’”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 25: 2-3).

The new disaster necessitated new troop dispositions:

-

“[Since] no practical method suggested itself for bringing the two consular armies up to sufficient strength for such an important war, ... [the Senate] decided to discontinue the campaign in Gaul for that year. The dictator's army was assigned to [Gracchus and] ... two legions raised in the City were allocated to ... [the other consul, who would] be elected as soon as favourable auspices could be obtained”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 25: 6-11).

Election of Verrucosus as Suffect Consul

Marcellus was despatched to Cales (on the border of Campania) to arrange the new troop dispositions and, on his return:

-

“... notice was given of the election of a consul in the place of L. Postumius. Marcellus was elected by a unanimous vote in order that he might take up his magistracy at once. However, as he was assuming the duties of the consulship, thunder was heard; the augurs were summoned and gave it as their opinion that there appeared to be a flaw in his election. The patricians spread a report that as that was the first time that two plebeian consuls were elected together, the gods were showing their displeasure. Marcellus [duly] resigned his office and Q. Fabius Maximus [Verrucosus] was appointed in his place. This was his third consulship”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 31: 12-14).

Livy had already recorded that:

-

“The people made an order investing M. Marcellus with the powers of a proconsul, because he was the only one out of the Roman commanders who had gained any successes in Italy since the disaster at Cannae”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 3o: 19).

However, as John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 95) observed, this was perhaps a consolation prize for his loss of the consulship.

Carthaginian Successes in Bruttium and Lucania

Blue = Carthaginian gains in 215 BC; Red = Rhegium, which remained loyal to Rome

Livy recorded that, at some time in the consular year:

-

“... Himilco, one of Hannibal's lieutenants, took Petelia in Bruttium after a siege that lasted several months. This victory cost the Carthaginians heavy losses in both killed and wounded, for the defenders only yielded after they had been starved out. ... [Himilco then] marched his army to Consentia. The defence here was less obstinate and the place surrendered in a few days. At about the same time, an army of Bruttians [easily] invested the Greek city of Croton. ... [The Greek city of] Locri also went over to the Bruttians and Carthaginians after the aristocracy of the city had betrayed the populace. Alone in all that country, the people of Rhegium, [which controlled the straits between Italy and Sicily]. remained loyal to the Romans and kept their independence to the end”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 30: 1-9).

Events in Campania

Campanian cities with civitas sine suffragio (underlined in red)

Red dot = Latin colony of Cales

Adapted from this map on the webpage on Roman Campania by Jeff Matthews

After his success at Casilinum, Hannibal established a base at Mount Tifata, north of Capua, although his resources in the area were reduced by the demands from Lucania and Bruttium (above). John Lazenby (referenced below, at pp. 96-7) described a number of setbacks that he suffered in Campania, probably as a result. Capua and his other Campanian allies tried to subvert the port city of Cumae , which appealed to Gracchus for assistance. Grachus marched from his base at Liturnum during the night and stormed the Campanian camp outside the Cumae before withdrawing to the safety of the city. Hannibal responded by attacking Cumae but was driven back to Mount Tifata. Perhaps as a result of this distraction, Verrucosus was apparently able to march from his base at Cales, past Casilinum and Capua and on to Suessula, where Marcellus was based. Marcellus himself moved to Nola. He repulsed Hannibal’s attempt to take this city and, when a body of Numidian and Spanish mercenaries deserted to Marcellus, Hannibal retired to winter quarters in Apulia with part of his army, while his general, Hanno, the rest of his army wintered in Bruttium.

Temples to Venus Erycina and Mens

The temples to Venus Erycina and Mens that had been vowed in 217 BC were both built within two years: Livy recorded that:

-

“Towards the close of [215 BC], Fabius asked the Senate to allow him to dedicate the temple of Venus Erycina, which he had vowed when dictator. The Senate passed a decree that T. Sempronius, the consul-elect, immediately upon his entering office, should propose a resolution to the people that Fabius be one of the two commissioners appointed to dedicate the temples”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 30: 13-14).

Soon after:

-

“... two commissioners were appointed for the dedication of temples:

-

✴T. Otacilius Crassus dedicated the temple to Mens; and

-

✴Q. Fabius Maximus dedicated the temple to Venus Erycina.

-

Both are on the Capitol, separated only by a water channel”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 31: 9).

Events of 214 BC

Livy recorded that, while Verrucosus was still on his way to Rome to organise the consular elections:

-

“... he gave notice that they would be held on the first election day that he could fix and then, in order to save time, he marched past the City straight to the Campus Martius. That day the first voting fell by lot to the junior century of the tribe of the Anio, and they were giving their vote for T. Otacilius and M. Aemilius Regillus, when Q. Fabius, having obtained silence [in order to address the assembled voting tribes]”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 7: 11-12).

Livy then reported Fabius’ address, in which he stressed the relative inexperience of the unfortunate T. Otacilius and M. Aemilius Regillus. He urged the misguided electors to:

-

“... choose the consuls today to whom your children [i.e. the recruits of the army] must take the oath, at whose edict they must assemble, under whose tutelage and protection they must serve. Trasimene and Cannae are melancholy precedents to recall, but they are solemn warnings to guard against similar disasters. Usher! call back the century of juniors in the tribe of the Anio to give their votes again”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 8: 19).

Thus it was that:

-

“... in the 5th year of the second Punic war, ... Q. Fabius Maximus assumed the consulship for the 4th time and M. Claudius Marcellus for the 3rd time. ... Marcellus was elected in his absence, while he was with the army. Fabius was re-elected when he was on the spot and actually conducting the election. Irregular as this was, the circumstances at the time, the exigencies of the war and the critical position of the State prevented anyone from inquiring into precedents or suspecting [Verrucosus] of love of power. On the contrary, they praised his greatness of soul because, when he knew that the Republic needed its greatest general, and that this general was unquestionably himself, he put the interest of the Republic ahead of any personal odium that he might incur”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 9: 7-11).

Hannibal returned to Campania at the start of the fighting season of 214 BC. He summoned Hanno to bring an army from Bruttium, via Beneventum, to join him. At the same time, Verrucosus (perhaps on the basis of intelligence) ordered Gracchus (now proconsul in Apulia) to move to Beneventum. Gracchus was thus able to intercept Hanno’s army at there: according to Livy, Gracchus’ army was made up largely of slaves, to whom he had offered freedom if they should defeat the enemy. This they duly did, albeit that Hanno and most of his cavalry escaped. Livy recorded that Gracchus:

-

“... on his return to Rome, ... ordered a representation of that celebrated day to be painted in the temple of Liberty: his father had built and dedicated this temple on the Aventine out of the proceeds of fines”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 16: 19).

Hannibal made attempts on Nola and then on Tarentum, both of which were unsuccessful, before establishing his winter camp in Apulia, while Verrucosus and Marcellus laid siege to Casilinum:

-

“[Verrucosus] was encamped before Casilinum, which was occupied by a garrison of 2,000 Campanians and 700 of the soldiers of Hannibal. The commander [of the rebel army] was Statius Metius, who was sent there by Cn, Magius Atellanus, who was that year meddix tuticus ... Marcellus left 2000 men to protect Nola and came with the rest of his army to Casilinum, ... [which] was taken. The Campanians and those of Hannibal's troops who were made prisoners were sent to Rome and imprisoned: the mass of the townsfolk were distributed amongst the neighbouring communities to be kept in custody”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 19: 1-11).

Events in Sicily (214 - 210 BC)

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

The Romans had ejected the Carthaginians from Sicily as a consequence of their victory in the First Punic War (264-41 BC). King Hiero II, the king of the ancient Greek city-state of Syracuse at the south east of the island, had signed a treaty with the Romans in 263 BC and had given them steadfast support thereafter. Thus, as Tenney Frank (referenced below, at p. 56) summarised, after the victory:

-

“The Syracusan state with its subject cities became an [independent] ‘amicus’ of Rome, and Messana and some of the other cities that had been independent before Rome’s arrival [on the island] became socii. The whole western portion, [previously] tributary to Carthage, now by right of conquest became tributary to Rome. ... [Thus, in 242 BC], Rome secured her first subject province ... .”

Livy recored that, after the defeat at Cannae in 216 BC:

-

“... even the house of Hiero did not altogether shrink from deserting Rome. Gelo, the eldest son of the family, treating with equal contempt his aged father and the alliance with Rome, went over to the Carthaginians ... : he was arming the natives and making friendly overtures to the cities in alliance with Rome, and would have brought about a revolution in Sicily had he not ... [met] a death so opportune that it cast suspicion even on his father”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 30: 10-12).

The alliance with Syracuse therefore remained in operation and, in 215 BC, after the Romans became aware of a treaty between the Carthaginians and Philip V of Macedonia:

-

“A decree was made that the money that had been sent to Ap. Claudius [Pulcher, the praetor based at Lilybaeum in western Sicily], for him to return to King Hiero should now be devoted to the maintenance of the fleet and the expenses of the Macedonian war ... At the same time, King Hiero sent 200,000 modii of wheat and barley [to Rome]”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 38: 12-13).

Ap. Claudius Pulcher (215 BC)

According to Livy, soon after Pulcher’s arrival in Sicily:

-

“... the position of the Romans was totally altered by the death of Hiero and ... the [succession of] his grandson, Hieronymus, who was but a boy ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 4: 1).

Hieronymus soon:

-

“... sent envoys to Carthage to conclude a treaty ... with Hannibal. Under this agreement, after [the Carthaginians] had expelled the Romans from Sicily, ... the river Himera, which almost equally divides the island, was to be the boundary between the dominions of Syracuse and that of Carthage. Puffed up by the flattery of people ... , Hieronymus [then] sent a second legation to Hannibal to tell him that he thought it only fair that the whole of Sicily should be ceded to him, and that Carthage should claim the empire of Italy as their own. [The Carthaginians] expressed neither surprise nor displeasure at this fickleness, ... provided only they could keep him Hieronymus declaring for Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 6: 6-9).

Although the terms of this agreement, as Livy described it, were clearly unrealistic, the Romans’ reaction to these developments indicate how critical Syracuse was to Roman control over Sicily. Ap. Claudius Pulcher entered into negotiations with Hieronymus but Hieronymus was murdered at nearby Leontini in 214 BC and:

-

“... Ap. Claudius saw that a war was inevitable and sent a despatch to the Senate informing them that Sicily was being won over to Carthage and Hannibal”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 7: 7).

In response, according to Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 681):

-

✴P. Cornelius Lentulus was sent as praetor of western Sicily;

-

✴Ap. Claudius Pulcher was temporarily prorogued and assigned to eastern Sicily; and

-

✴T. Otacilius (the unsuccessful candidate for the consulship of 214 BC), had his praetorian naval command extended and moved his base to Sicily.

More importantly, Marcellus was dispatched to Sicily.

M. Claudius Marcellus (as Consul in 214 BC)

According to Arthur Eckstein (referenced below, at p. 349), Marcellus travelled from Nola to Sicily in the late summer or early autumn of 214 BC. According to Livy, Marcellus’ arrival gave rise to:

-

“... heated discussions [at Syracuse], but finally, as there appeared to be no possible means of carrying on a war with Rome, it was decided to conclude a peace and to send an embassy along with the envoys who had come from Marcellus to obtain its ratification”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 28: 9).

However, almost immediately, the Syracusans answered an appeal from nearby Leontini from protection from what was probably an undisciplined section of the Roman army. Things subsequently spiralled out of control. Briefly, the Romans took Leontini, following which two pro-Carthaginian brothers, Hippocrates and Epicydes, took control at Syracuse. Marcellus offered terms, to which Epicydes apparently replied:

-

“When the government of Syracuse is in the hands of [the old, pro-Roman régime], then you can return [with an offer of this kind. Meanwhile], if you provoke us to war, you will learn by experience that attacking Syracuse is not quite the same thing as attacking Leontini. With these words, he left the envoys and closed the gates. Then [the Romans began] a simultaneous attack by sea and land ... on Syracuse”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 33: 7-8).

According to John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 105) and Arthur Eckstein (referenced below, at p. 349), this probably occurred in the spring of 213 BC.

M. Claudius Marcellus (as Proconsul in 213 BC)

According to Livy, in 213 BC:

“The commands were extended in the following cases: M. Claudius [Marcellus] was to retain the part of Sicily that had constituted Hiero's kingdom, [while P. Cornelius] Lentulus [was to continue] as propraetor ... [in] the old province”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 44: 3).

Marcellus’ attack on the walls of Syracuse unexpectedly failed, apparently in part because of the anti-siege weapons that had been designed by the great Archimedes. Thus, Livy recorded that:

-

“... since all their attempts were frustrated, the Romans decided to desist from active operations and to confine themselves simply to a blockade, and cut off all supplies from the enemy, by both land and sea”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 34: 16).

According to Livy, Marcellus left most of his army at Syracuse and took the rest on a campaign:

-

“... to recover the cities that had seceded to the Carthaginans in the general disturbance: Helorum and Herbesus immediately submitted. Megara was taken by assault, sacked and completely destroyed in order to strike terror into the rest, especially Syracuse”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 35: 1-2).

However, the Carthaginians sent an army under Himilco to Sicily. He succeeded in establishing a base at Agrigentum, which raised morale at Syracuse and at other rebel cities. Marcellus had attempted to reach Agrigentum in advance of the Carthaginians, but returned to Syracuse when he realised that he was too late. The Carthaginians then marched on Syracuse and also landed a fleet there, and:

-

“It looked as if the war had been wholly diverted from Italy, so completely were both peoples devoting their attention to Sicily”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 36: 4).

Fortunately, Pulcher soon arrived with reinforcements, and Himilco decided that he would be better employed by encouraging other Sicilian cities to throw off Roman rule. This proved to be a sound strategy, when:

-

“He began with the capture of [the Roman supply depot at] Murgantia, where the populace betrayed the Roman garrison, and where a large quantity of corn and provisions of all kinds had been stored for the use of the Romans”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 36: 10).

The Romans discovered plans for another rebellion at Henna, and subsequently massacred its inhabitants:

-

“So, Henna was saved for Rome by a deed that was criminal, even if it was not unavoidable. Marcellus not only passed no censure on the transaction, but even bestowed the plundered property of the citizens upon his troops, thinking that, inspired by the terror, the Sicilians would be deterred from betraying other garrisons. The news of this occurrence quickly spread through Sicily, for henna, lying in the middle of the island, was no less famous for the natural strength of its position than it was for the sacred associations which connected every part of it with the old story of the Rape of Proserpine. It was universally felt that a foul and murderous outrage had been offered, to the abode of gods as well as to the dwellings of men, and many who had before been wavering now went over to the Carthaginians”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 39: 7-9).

It seems that winter was now approaching:

-

“Marcellus marched back to Leontini and, after collecting supplies of corn and other provisions for the camp, he left a small detachment to hold the city and returned to the blockade of Syracuse. He gave [Pulcher] permission to go to Rome to carry on his candidature for the consulship [of 212 BC]”, (‘History of Rome’, 24: 39: 12).

M. Claudius Marcellus (as Proconsul in 212 BC)

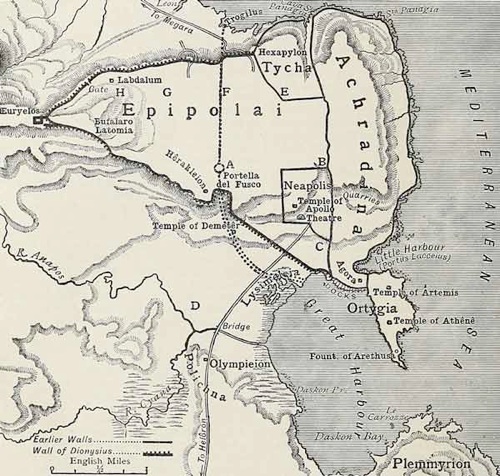

From W. Smith, “A Classical Dictionary Biography Mythology and Geography”

(revised and reP.hed in 1894) London and New York, at p. 908

This was a crucial moment in the war: as John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 115) observed, Hannibal now controlled most of southern Italy and:

-

“... if Sicily could have been won, he might have been able to establish secure communications with Carthage and open up a ‘second front’ in Italy.”

This is presumably why, as Livy (‘History of Rome’, 25: 3: 6) recorded, the commands of both Marcellus and P. Cornelius Lentulus were prorogued in 212 BC.

Livy noted that, by this point, Marcellus had realised that Syracuse:

-

“ ... was unassailable by sea or land owing to its position, and that it could not be reduced by famine, since it enjoyed a free supply of provisions from Carthage. However, he determined to leave nothing untried”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 23: 4).

The chance came when he heard that the Syracusans were celebrating the festival of Artemis, and that the authorities there had provided wine in abundance. Knowing that the feast would draw most of the inhabitants towards the Ortygia island (the heart of the ancient city), Marcellus took the opportunity to force the Hexapylon gate and to take the plateau of the Epipolai, which was above the heavily fortified Achradina (outer city). When Epicydes realised what had happened, he took refuge in the Achradina, while Marcellus:

-

“... established his camp between Neapolis and Tycha (which were parts of the city and, indeed, almost cities in themselves) ... Envoys came to him from these two places, ... imploring him that they might be spared from fire and sword. Marcellus ... gave notice to the soldiers that they were not to lay hands on any free citizen; they were at liberty to appropriate everything else”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 25: 5-7).

At this point, the commander of the fortess at Euryalos (at the western end of the Epipolai) surrendered on condition that he and his men could join Epicydes in the Achradina. Himilcar and Hippocrates soon arrived from Agrigentum and attacked the Roman camp that was probably at the Olympieion (south of the city. It was now autumn, and this riverine area was engulfed by disease. According to Livy:

-

“The epidemic was much more prevalent in the Carthaginian camp than in that of the Romans ... The Sicilians who were in the hostile ranks deserted ..., and went off to their own cities. The Carthaginians, who had nowhere to go to, perished to a man, together with their generals, Hippocrates and Himilco. When the disease assumed such serious proportions Marcellus transferred his men to the city ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 26: 12-15).

A fleet sent from Carthage commanded by Bomilcar now approached the city, and Epicydes sailed out to meet it:

-

“When Marcellus became aware that an army of Sicilians was being raised from the whole of the island, and that [this] Carthaginian fleet was approaching with vast supplies, he determined that, although he had fewer ships, he would attempt to prevent Bomilcar from reaching Syracuse, [where he would be] shut in by sea and land and confined and hampered in a hostile city. The two fleets lay facing each other off the promontory of Pachinus, ready to engage when the sea was calm enough to allow them to sail into deep water. As soon as the east wind ... dropped Bomilcar made the first move. It seemed as though he was making for the open sea in order the better to round the promontory but, when he saw the Roman ships sailing straight for him, he crowded on all sail and skirting the coast of Sicily made for Tarentum (which had been taken by Hannibal - see below), having previously sent a message to Heraclea ordering the transports to return to Africa. Finding all his hopes suddenly crushed, Epicydes did not care to go back to Syracuse, which was in a state of siege and a large part of which was already taken. He sailed for Agrigentum, to watch events rather than to control them”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 27: 9-13).

Marcellus agreed terms of surrender with a new government that had seized power in Syracuse after Epicydes’ departure. However, this was vitiated when this new government was itself overthrown. At this point, a Spanish mercenary commander named Moericus arranged for the Romans to enter Ortygia from the southern gate (near the Fountain of Arethusa):

-

“When Marcellus learnt that [Ortygia] was captured and that one district of Achradina was occupied, ... he ordered the retreat to be sounded, for he was afraid that the royal treasure, the fame of which exceeded the reality, might fall into the hands of plunderers”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 30: 12).

This proved to be a very good move:

-

“The impetuosity of the soldiers being thus checked and time and opportunity given for the [Roman] deserters in Achradina to effect their escape, the Syracusans were at last relieved of their apprehensions and opened the gates”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 31: 1).

The long siege was over: according to Arthur Eckstein (referenced below, at p. 119) and John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 119), this took place towards the end of 212 BC.

The extent to which Marcellus allowed his men to pillage the city is difficult to establish. Livy noted that he:

-

“... sent the quaestor with an escort to [Ortygia] to receive the royal treasure into his custody. Achradina was given up for plunder to the soldiers, after guards had been placed at the houses of the [pro-Roman Syracusan] refugees who were within the Roman lines. The fate of Archimedes, [who was murdered by Marcellus’ soldiers], stands out amongst many horrible instances of fury and rapacity. ... Such, in the main, were the circumstances under which Syracuse was captured, and the amount of plunder was almost greater than it would have been if Carthage had been taken”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 31: 8-12).

Polybius’ main account of these events is now lost: the surviving fragment begins with the information that:

-

“The Romans, then, decided for [a now-lost] reason to transfer all these [now unidentified] objects to their own city, and to leave nothing behind”, (‘Histories’, 9: 10: 2).

He then embarked on a discussion of the moral and political dangers of depredations such as this, before acknowledging that:

-

“There were, indeed, perhaps good reasons for appropriating all the gold and silver [of Syracuse]: for it was impossible for [the Romans] to aim at a world empire without weakening the resources of other peoples and strengthening their own”, (‘Histories’, 9: 10: 11).

It is certainly true that this gold and silver would have been very welcome in Rome at this particular moment in the war.

Events of 211 BC (M. Claudius Marcellus as Proconsul)

According to Livy it was decided at the start of the next consular year that:

-

“M. [Claudius] Marcellus’ imperium was ... prorogued to enable him to terminate as proconsul what remained of the war in Sicily with the army under his command; if he needed it supplemented, he was to supplement it from the legions that P. Cornelius [Lentulus] commanded as propraetor in Sicily, but with the further provision that, [if he returned to Rome while hostilities continued, he would [leave behind all] of the men whom the Senate had denied discharge or repatriation before the war ended”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 1: 6-9).

Thus, Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 689) reasonably assumed that a new praetor called C. Sulpicius replaced P. Cornelius Lentulus in western Sicily, and that Marcellus was replaced during the year by M. Cornelius Cethegus (see below), as praetor in eastern Sicily.

Livy recorded that, after the fall of Syracuse:

-

“Whilst Marcellus was settling the affairs of Sicily, deputations came to him from nearly all the communities in the island. The treatment they received varied with their circumstances:

-

✴those that had not revolted or had returned to Roman allegiance prior to the capture of Syracuse were welcomed and honoured as socii fideles (loyal allies); while

-

✴those who had surrendered only after Syracuse had been taken had to accept the terms that a victor usually imposes on the vanquished”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 40: 4).

Arthur Eckstein (referenced below, at p. 166) considered Marcellus’ decision to overlook temporary Sicilian defections as idiosyncratic. This settlement seems to have covered most of the island. However, as Livy pointed out, Epicydes and the Carthaginian generals Hanno still held Agrigentum and Hannibal had sent them a force of Numidians, with the result that some other pro-Carthaginian cities remained hopeful that help was at hand. The Carthaginians marched out of Agrigentum towards Syracuse, and Marcellus marched out to meet them, having reached a secret agreement with the Numidians that they would desert:

-

“When the opposing lines met, the Numidians were standing quietly on the wings. When they saw their own side turn tail, they initially joined them in their flight, but when they saw them heading for Agrigentum, they dispersed to the neighbouring cities for fear of having to withstand a siege. Several thousand men were killed and eight elephants captured. This was the last battle Marcellus fought in Sicily: after this victory, he returned to Syracuse”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 41: 7-8).

According to Livy:

-

“At the end of the ... summer [of 211 BC], when M. [Claudius] Marcellus arrived at Rome from his province of Sicily, C. Calpurnius, the praetor, granted him a session of the Senate in the temple of Bellona [outside the pomerium]. There, after speaking of his achievements he complained gently, not so much on his own account as on behalf of his soldiers, that, even after completing his task in the province, he had not been permitted to bring home his army. He also demanded that he be permitted to enter the city in triumph. That request was not granted”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 21: 1-3).

Livy represented the two sides of the argument as follows:

-

✴Marcellus’ supporters argued that, since a supplicatio (thanksgiving} had been decrees in his name for successes gained under his command, and honour had been rendered to the gods while he had still been in Sicily, it followed that he should triumph on his return.

-

✴His opponents argued that he could not celebrate a triumph in relation to his achievements in Sicily for two related reasons:

-

•the war that he had been prosecuting was still in progress, as evidenced by the fact that the Senate had ordered him to turn his army over to a successor; and

-

•his army was therefore unable to witness the triumph that he requested, it was whether deserved or undeserved.

The Senate decided to compromise by offering Marcellus an ovation, an offer that he accepted. However:

-

“On the day before his entry into the city,[Marcellus] triumphed on the Alban Mount, [an honour that he granted to himself by virtue of his imperium]. Then, in his ovation, he arranged for a large amount of booty to be carried before him into the city. A representation of captured Syracuse was carried, together with:

-

✴catapults and ballistae and all the other engines of war;

-

✴a quantity of silverware and bronzeware, other furnishings and costly fabrics, the adornments of a long peace and of royal wealth; and

-

✴many notable statues, with which Syracuse had been adorned more highly than most cities of Greece.

-

Furthermore, as a sign of triumph over Carthaginians, eight elephants were included in the procession. And finally, not the least spectacle, Sosis of Syracuse and Moericus the Spaniard, both of whom had opened gates at Syracuse for Marcellus’ army], marched in advance of Marcellus, wearing golden wreaths, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 21: 1-3).

Events of 211 BC (M. Cornelius Cethegus as Praetor)

It seems that, before leaving Sicily, Marcellus had handed his army over to a praetor, M. Cornelius Cethagus. At some time thereafter:

-

“... a Carthaginian fleet landed 8,000 infantry and 3,000 Numidian cavalry [on Sicily, at which point], Murgentia and Ergetium revolted, ... followed by Hybla, Macella and some other towns of less importance. [Furthermore], the Numidians, ... under their prefect Muttines, burned the lands of allies of the Roman people. In addition, the Roman army was demoralised, partly because it had not been transported out of the province along with [Marcellus] and partly because they had been forbidden to winter in towns ... In the midst of these difficulties, the praetor M. Cornelius [Cethegus, who had replaced Marcellus], restored the spirits of his men] and reduced to subjection all the city-states that had revolted ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 21: 14-17).

At the start of the next consular year, Livy recorded that the Senate decided that:

-

“... the army that M. Cornelius [Cethegus] had commanded was [finally] to be sent home from Sicily”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 28: 10).

Events of 21o BC

Marcellus arrived in Rome in time to compete in the consular elections, and was duly elected to his 4th consulship. His colleague was M. Valerius Laevinus, who had met with considerable success in Greece and Macedonia as propraetor in 214-1 BC. Marcellus drew Sicily in the ballot for provinciae, but (for reasons discussed below) he exchanged provinces with his colleague (who had drawn Italy).

According to Livy, it was late in the consular year when:

-

“... Laevinus, the consul, arrived in Sicily, where the old and the new allies awaited him. He therefore thought it of the very first importance to settle affairs that were in disorder at Syracuse, owing to the short time since the peace. Then he led his legions to Agrigentum, which was still held by a strong garrison of Carthaginians”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 40: 1-2).

The garrison was still commanded by Hanno and Epicydes, supported by Muttine and his Numidian cavalry. Muttines now secretly agreed with Laevinus that he would desert his allies, and he then duly arranged for the gate at Agrigentum nearest the sea to be opened to the Romans. The city descended into uproar:

-

“Hanno, thinking that it was nothing more than an outbreak and mutiny of the Numidians, as had happened before, went forth to quell the uprising. However, when he caught sight of a crowd in the distance that clearly exceeded the number of the Numidians, and when the shouts of the Romans ... reached his ears, he took to flight ... . Escaping by the gate farthest from the enemy and taking Epicydes and a few others as his companions, he made his way to the sea, where he found a small vessel and crossed over to Africa, leaving Sicily, ... to the enemy. The rest of the Carthaginians and Sicilians [from Agrigentum] were blindly fleeing without even attempting to fight, but the ways of escape had been closed, and they were killed en masse near the gates. On gaining possession of the stronghold, Laevinus scourged and beheaded the responsible men at Agrigentum and sold the rest and the booty. He sent all the money [that he raised] to Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 40: 9-13).

News of this Roman victory led to a collapse in Carthaginian support on the island. Laevinius was able to re-establish Roman control in the the last rebellious centres and to arrange for the farmers to return to the production of food for Sicily itself and for Rome and Italy. Hi despatched an collection of unruly reprobates to the army at Rhegium:

-

“... who were looking for a band accustomed to brigandage in order to devastate the territory [held by Hannibal] in Bruttium. As far as Sicily, was concerned, the war was [over]”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 40: 18).

Revolt of Tarentum (212 BC)

Blue = Carthaginian gains in 215 and 212 BC;

Red = Rhegium, which remained loyal to Rome and Venusia, a Latin colony

Tarentum, which was the leading city in Magna Grecia, had been a loyal Roman ally since 271 BC, and had supported the Romans throughout the First Punic War. However, its loyalty had been weakened by the Roman defeat at Cannae, and the Romans had responded by posting a garrison there and by taking hostages to ensure the continuing ‘good behaviour’ of the Tarentines . However, Hannibal had been attracted by the prospect of an alliance with the Tarentines, largely because of their magnificent port, and had been receiving approaches from dissident factions since at least 214 BC. Thus, Livy recorded that:

-

“The betrayal of Tarentum had long been an object of hope with Hannibal and of suspicion with the Romans, and now [in 212 BC], an incident that occurred outside its walls hastened its capture”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 7: 10).

The incident occurred when a Carthaginian sympathiser from Tarentum persuaded the Tarentine hostages at Rome, along with others from Thurii, to escape:

-

“They were caught at Tarracina and brought back [to Rome]; then they were marched into the Comitium and, with the approval of the people, scourged with rods and thrown from the [Tarpeian] Rock. The cruelty of this punishment produced a feeling of bitter resentment in the two most important Greek cities in Italy ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 25: 7: 14 - 25: 8: 1).

Soon thereafter, the gates of Tarentum were opened for Hannibal, and he easily took the city, albeit that the Roman survivors found refuge in its citadel: Livy was not sure of the precise date of the revolt at Tarentum, but John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 110) argued that it must have occurred in late March or April, 212 BC. Lazenby (at p. 112) also recorded that it was soon followed by the defections of the other Greek cities of Thurii, Metapontum and Heraclea.

Events in Campania (212 - 211 BC)

According to Livy (‘History of Rome’, 25: 3: 1), the consuls elected for 212 BC were Q. Fulvius Flaccus (for the third time) and Ap. Claudius Pulcher, both of whom were assigned to Campania. The Capuans and many of the other rebels there had been prevented from sowing crops in the previous years, and Hannibal was unable to answer their pleas for supplies. According to John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 115), the consuls succeeded in surrounding and laying siege to Capua in late 212 BC. Both consuls were prorogued as proconsuls in 211 BC in order to continue the siege, and they were joined by C. Claudius Nero, as propraetor. As the situation of the Capuans became desperate, Hannibal marched to their relief, but was defeated: Livy recorded that:

-

“... this was the last battle [that was fought] before the surrender of Capua. Seppius Loesius, who was [then] serving as medix tuticus [at Capua] ... was the last of all the Campanians to receive [this], their highest magistracy”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 6: 13-17).

Hannibal then decided to draw the Romans away from Capua by marching on Rome. Although Livy had conflicting sources for Hannibal’s route, John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 122) argued that he probably avoided the direct route along the Via Latina and instead diverted to the east, through Samnium, Latium and the Sabine lands and into Etruria. He certainly sacked the temple at the lucus Feroniae near Capena (‘History of Rome’, 26: 11: 8) before turning south towards Rome. Having crossed the Anio, he camped a few kilometres from the Colline Gate. However, it seems that, when he learned that Capua remained firmly besieged by the Roman army, he rapidly recrossed the Anio and probably abandoned Capua by marching directly to Rhegium. John Lazenby (as above) observed that:

-

“It was typical of Hannibal that, when one gamble had failed, he should immediatelt try to retrieve the situation by surprise in another place.”

The Capuans had now lost their only chance of immediate salvation. According to Livy, after a heated debate:

-

“... the majority of the senate of Capua, not doubting that the clemency of the Roman people, ... voted and sent legates to surrender Capua to the Romans”, (‘Roman History’, 26: 14: 2).

Livy then described the surrender of the remaining rebel cities:

-

“Atella and Calatia surrendered themselves, and were received. Here also the principal promoters of the revolt were punished. Thus 80 principal members of the senate were put to death, and about 300 of the Campanian nobles thrown into prison. The rest were distributed through the several cities of the Latin confederacy, to be kept in custody, where they perished in various ways. The rest of the Campanian citizens were sold [into slavery]”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 16: 4).

Livy described the debate in Rome that decided the fate of Capua:

-

“Some [Roman senators] were of opinion that a city] so eminently powerful, so near and so hostile [to Rome as Capua] ought to be demolished. However, i wiser counsel] prevailed: since its territory was well known to be [among the most fertile] in Italy ... , the city was preserved, so that [presumably Roman] farmers of the land might have some abode. ... The multitude of resident aliens and freedmen and petty tradesmen and artisans was [allowed to remain in the city. Its] entire territory and the buildings became public property of the Roman people. ... the mass of citizens were scattered with no hope of a return”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 16: 7-11).

Finally, he reported that Capua was deprived of its civic status:

-

“It was decided that Capua, as a nominal city, should merely be a ... centre of population, and that it should have no political body nor senate nor council of the plebs nor magistrates. ... the Romans would send out every year a prefect to administer justice. No rage was vented upon innocent buildings and city walls by burning and demolition”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 16: 9-11).

We know from Velleius Paterculus that this administrative vacuum persisted at Capua until 59 BC, when Julius Caesar arranged for the foundation of a colony here:

-

“In this consulship, Caesar, with Pompey's backing, passed a law authorising a distribution to the plebs of the public domain in Campania. And so about 20,000 citizens were established there, and its rights as a city were restored to Capua 152 years after she had been reduced to a prefecture in the Second Punic War”, (‘Roman History’, 2: 44: 4).

It seems that Ap. Claudius Pulcher died at around the time of the fall of Capua. John Rich (referenced below, at p. 222) observed that:

-

“Livy and other narrative sources make no reference to a triumphal application from Fulvius for this achievement, but Valerius Maximus claims that he applied and was refused, explaining that the Senate acted:

-

“ ... from utmost care to observe the law, which provided that a triumph [should] be decreed [only] for augmentation of empire, not for the recovery of what had [already] belonged to the Roman people”. (translated by David Shackleton Bailey,referenced below, at p. 205).

Rich argued that:

-

“In this form, the alleged rule must be spurious, since triumphs were often awarded following the suppression of rebellions. However, it is possible that a triumph for the recovery of Capua was felt to be inappropriate because, before their revolt, its people had been Roman citizens (albeit without the vote), and [it was for this reason that] Fulvius ... either did not seek a triumph or, if he did, was refused.”

Southern Italy (210 - 208 BC)

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Events in Apulia (210 BC)

As noted above, M. Claudius Marcellus was elected as one of the consuls of 210 BC and, although he had drawn Sicily in the ballot for provinciae, he had exchanged it for Italy. The fall of Capua in the previous year had weakened Hannibal’s standing with his remaining allies. This was particularly the case in Apulia, which had received little attention from Hannibal since its defection to him after Cannae. Arpi had already returned to Roman allegiance in 213 BC, and Marcellus received news that the coastal town of Salapia, which was garrisoned by a unit of 5,000 Numidian cavalry, was similarly inclined. According to Livy, the citizens of Salapia voluntarily surrendered to Marcellus but:

-

“... the surrender could only be effected with a heavy loss of life. The [Numidian] garrison were by far the finest cavalry in the Carthaginian army and, although they were taken by surprise and could make no use of their horses in the city, they seized their arms in the confusion and attempted to cut their way out. When they found escape impossible, they fought to the last man. Not more than fifty fell into the hands of the enemy alive. [14] The loss of this troop of horse was a heavier blow to Hannibal than the loss of Salapia; never from that time was the Carthaginian superior in cavalry, hitherto by far his most efficient arm”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 38: 12-13).

Marcellus then moved his centre of operations to Samnium.

Cn. Fulvius Centamulus, who had commanded in Apulia as consul in 211 BC, had had his command here prorogued in 210 BC. He now approached nearby Herdonea, which was rumoured to be considering defection. However, Hannibal unexpectedly fell on his army after it had established a camp outside Herdonea. This time, Hannibal’s Numidian cavalry was instrumental in securing a major Roman defeat:

-

“It was here that Cn. Fulvius fell, together with eleven military tribunes. As to the number of [other Romans that were] killed, who could definitely state it, when I find in one author the number given as 13,000, in another not more than 7000? [Hannibal] took possession of the camp and its spoil. As he learnt that Herdonea had been prepared to go over to the Romans and that it would not remain faithful after his withdrawal, he transported the whole population to Metapontum and Thurii, and burnt [Herdonea]. Its leading citizens, who were discovered to have held secret negotiations with Fulvius, were put to death. Those Romans who escaped from the fatal field fled by various routes, almost wholly weaponless, to Marcellus in Samnium”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 1: 13-15).

On hearing the news, Marcellus marched from Samnium and caught up with Hannibal at Numistro in Lucania. Livy described a ferocious day-long battle:

-

“Night, however, separated the combatants while the victory was yet undecided. ... Hannibal broke up his camp quietly at night and withdrew into Apulia. When daylight revealed the enemies' flight, Marcellus ... left the wounded with a small guard at Numistro under the charge of L. Furius Purpurio, one of his military tribunes, and came up with Hannibal at Venusia. Skirmishes took place here for some days ... Both armies [then] traversed Apulia without any significant fighting ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 2: 9-12).

Recovery of Tarentum (209 BC)

Marcellus’ command was prorogued in 209 BC, when he campaigned with the consuls, Q. Fabius Maximus Verrucosus (in overall command) and Q. Fulvius Flaccus. According to Livy, after the new consuls had been elected, they:

-

“... set out for the war. Fulvius went first and led the way to Capua. After a few days, he was overtaken by Fabius, who implored [Fulvius] in person and Marcellus by letter to keep Hannibal occupied by the most spirited fighting possible while he himself was attacking Tarentum”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 12; 1-2).

He also sent a message to the commander of the garrison from Sicily that was now stationed at Rhegium (see above), ordering him to take these men into Bruttium, where they should devastate the country and then attack the city of Caulonia.

In response to Fabius request, Marcellus engaged with Hannibal outside Canusium, which was still faithful to Rome. Livy reported two engagements, the first a Roman defeat (‘History of Rome’, 27: 12) and the second a notional victory that was:

-

“... anything but a bloodless one for the Romans; out of the two legions some 1,700 men were killed and 1300 of the allied contingents, besides a very large number of wounded in both divisions. The following night, Hannibal shifted his camp. Marcellus, though anxious to follow him, was unable to do so owing to the enormous number of wounded. Reconnoitring parties who were sent out to watch his movements reported that he had taken the direction of Bruttium”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 14; 13-14).

Thus, Fabius’ strategy was working (albeit at a heavy cost): Hannibal had marched off to defend Caulonia. Meanwhile, Fulvius succeeded in adding to Hannibal’s problems: according to Livy:

-

“At about this time, the Hirpini [and] the Lucani, including the people of Volcei, surrendered to ... Fulvius and delivered up the garrisons that Hannibal had placed in their cities. He accepted their submission graciously, and only reproached them for the mistake they had made in the past. This led the Bruttians to hope that they might receive similar indulgence, and they sent the two men who were of highest rank amongst them ... to ask for favourable terms of surrender”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 15; 1-3).

While Hannibal was engaged at Caulonia, Fabius began his own campaign by taking the town of Manduria, near Tarentum. He then established his camp at the mouth of the harbour of Tarentum as the Roman fleet that had been supplying the men in the citadel prepared to attack the city. Fabius also secured the help of a Bruttian who had been enlisted in the army besieging the citadel, through whom he managed to get subvert the Bruttian unit that was manning its walls. He orchestrated a diversions from the fleet and from the men in the citadel, which allowed his men to scale the walls held by the Bruttians, and Tarentum was taken while Hannibal was still marching towards it from Caulonia (‘History of Rome’, 27: 16: 1-2). According to Livy:

-

“After the carnage, [the Romans sacked] the city. It is said that 30,000 slaves were captured together with an enormous quantity of silver plate and bullion, 83 pounds' weight of gold and a collection of statues and pictures almost equal to that which had adorned Syracuse. Fabius, however, showed a nobler spirit than Marcellus had exhibited in Sicily; he kept his hands off that kind of spoil. ... The wall that separated the city from the citadel was completely demolished”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 16: 7-9).

According to a copy from Arezzo of the elogium of Fabius (CIL XI 8128) from the Forum Augustum, the original of 2 BC would have recorded that:

-

“As consul for the fifth time, [Fabius] captured Tarentum and celebrated a triumph”, (translated on the Attalus website, search on ‘Tarentum’).

If this were correct, it would be the first triumph of the war. However, it is significant that Livy did not record this triumph (albeit that Plutarch, a much later source, did so at ‘Life of Fabius Maximus’, 23: 2). Miriam Pelikan Pittenger (referenced below, at pp. 304-5) was ambivalent, although she suggested that the triumph in this elogium might have been:

-

“... one of the false honours for which the ‘elogia’ are so notorious.”

Jessica Clark (referenced below, 1t p. 82 and not 89) took a similar view, but John Rich (referenced below, at p. 222 and note 126) saw no reason to doubt that the record of the triumph in the elogium was authentic.

Livy recorded that, at the end of the consular year, Marcellus faced some sort of trial in the Circus Flaminius. An unnamed tribune of the plebs argued that:

-

“While the Roman people were [paying the price] for the extension of Marcellus' command, his army after its double defeat [near Canusium], was now passing the summer comfortably housed in Venusia. Marcellus made a crushing reply to the tribune's speech by simply recounting all that he had done, with the result that the proposal to deprive him of his command rejected and the centuries unanimously elected him consul on the following day. T. Quinctius Crispinus, who was then serving as praetor[ at Capua], was assigned to him as his colleague”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 21: 4-5).

Death of Marcellus (208 BC)

In Construction

As Plutarch observed, Marcellus:

-

“... had passed his 60th year when he entered upon his 5th consulship”, ( ‘Life of Fabius Maximus’, 28: 3).

He and his colleague T. Quinctius Crispinus (his legate at Tarentum) were both assigned provinciae in southern Italy.

Plutarch also recorded that, before Marcellus left for his province:

-

“He wished to dedicate the temple to Honour and Virtue, which he had built out of his Sicilian spoils, but was prevented from doing so by the priests, who insisted that two deities could not occupy a single temple. He therefore began to build another temple adjoining the first, although he resented the priests' opposition and regarded it as a bad omen”, (‘Life of Marcellus’, 28: 1).

Livy recorded that, after his election to his 5th consulship in 208 BC, Marcellus:

-

“... was detained in Rome by [a number of religious problems, ... one being] that, although he had vowed a temple to Honos and Virtus at Clastidium during the Gallic War [as consul for the 1st time in 222 BC], the pontiffs impediebatus (were impeding) its dedication; for they insisted that unam cellam amplius quam uni deo recte dedicari (one cella could not properly be dedicated to more than one god) ... So, a temple of Virtus was added. Even so, the temples were not dedicated by Marcellus himself ”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 25: 7-10).

Marcellus took command of the army at Venusia. While on a reconnaissance mission with Crispinus, and a small band of 220 horsemen, the group was ambushed and nearly completely slaughtered by a much larger Carthaginian force of Numidian horsemen. Marcellus was impaled by a spear and died on the field, and Crispinus died of his wounds shortly afterwards.

Hasdrubal’s Invasion of Cisalpine Gaul (207 BC)

By 208 BC, Hannibal’s Italian campaign was running out of steam, and he was essentially confined to Bruttium and Lucania in southernmost Italy. However, his fortunes temporarily improved in that year, when both consuls, M. Claudius Marcellus and T. Quinctius Crispinus, were killed in a Carthaginian ambush near the Roman colony of Venusia. Furthermore, the Romans became aware that Hannibal’s brother, Hasdrubal, was planning to invade Italy and come to his aid. Thus, according to Livy:

-

“Inasmuch as a very dangerous year seemed impending, and the state had no consuls, everyone turned to the consuls-elect [C. Claudius Nero and M. Livius Salinator] and wished that they should cast lots for their provinces as soon as possible ... The provinces assigned to them were not locally indistinguishable, as in the preceding years, but separated by the whole length of Italy:

-

✴to [Claudius Nero] was assigned the land of the Bruttii and Lucania facing Hannibal; and

-

✴to [Livius Salinator, Cisalpine] Gaul, facing Hasdrubal, who was reported to be already nearing the Alps”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 35: 5-10).

Livy continued that:

-

“All the senators were ... of the opinion that the consuls must take the field at the earliest possible moment, for they felt that:

-

✴Hasdrubal must be met as he came down from the Alps, to prevent his stirring up the Cisalpine Gauls or Etruria, [areas that were] already aroused to the hope of rebellion; while

-

✴Hannibal must be kept busy with a war of his own, so that he might not be able to leave the country of the Bruttii and go to meet his brother.

-

Nevertheless Livius was hesitating, having small confidence in the armies of his provinces ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 38: 6-8).

However, Hasdrubal’s unexpectedly early arrival spurred everyone into action:

-

“At Rome, the confusion was increased by the receipt of a letter from Gaul written by Lucius Porcius, the praetor, reporting that Hasdrubal had left his winter quarters and was already crossing the Alps; that 8,000 Ligurians, enrolled and armed, would join him after he had crossed into Italy ... This letter constrained the consuls to complete the levy in haste and to leave for their provinces earlier than they had planned, with this intention: that each of them should keep [one of the] enemy in his province, and not allow them to come together and combine their armies ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 39: 1-83).

Hasdrubal duly arrived in the Po valley and attempted the siege of Placentia, from where he sent letters to Hannibal proposing that they should meet in Umbria. This might have been a diversionary action: the letters were intercepted, as perhaps was the intention, and Hasdrubal did not cross the Apennines but headed directly for the Adriatic. Livy recorded that:

-

“[Livius Salinator’s] camp was near Sena [Gallica], and about 500 paces away was Hasdrubal”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 46: 4).

Claudius Nero secretly led a detachment of men on a forced march of some 250 miles, in order to reinforce Livius’ army at Sena Gallica. However, Hasdrubal saw through this ruse and decided to withdraw under cover of darkness. According to Livy:

-

“In the excitement and confusion of the night the [local and potentially disloyal] guides were not closely watched [by Hasdrubal’s men]: one of them [hid], while the other swam across the river Metaurus ... So the [Carthaginian] column, deserted by its guides, wandered at first about the country, and a considerable number ... [deserted]. Hasdrubal ordered [his men] to move along the bank of the river, until daylight ... should show a favourable crossing. But, inasmuch as the farther he marched away from the sea the higher were the banks that confined the stream, he could not find a ford: [thus,] by wasting the day, he gave the [Romans] time to overtake him”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 47: 8-11).

Although the topographical details in this and other surviving sources are difficult to reconcile, it seems that Hasdrubal had marched north from Sena Gallica and then, unable to cross the Metaurus, had turned inland. The point at which the Romans caught up with him is uncertain, but the result is not: his cause lost, Hasdrubal accepted glorious defeat and died with most of his army. Livy (28: 9: 6) recorded that the consuls were awarded a joint triumph.

Even accounting for the likely exaggeration in the surviving accounts, it is difficult to avoid the impression that this was widely perceived to be the turning point in the war with Carthage. According to Livy, when the rumours 0f the victory that were soon reaching Rome were confirmed by the official reports:

-

“The Senate decreed that, whereas M. Livius and Gaius Claudius, ... with their army safe, had slain the general and legions of the enemy, there should be a thanksgiving for three days. ... All the temples were uniformly crowded for all three days, while the matrons in their richest garments, together with their children, being relieved of every fear, just as if the war were already finished, returned thanks to the immortal gods. ... Gaius Claudius, ...having returned to his camp, ordered that the head of Hasdrubal ... be thrown in front of [Hannibal's] outposts ... Hannibal, under the blow of so great a sorrow, at once public and intimate, is reported to have said that he recognised the destiny of Carthage”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 51: 8-12).

As noted above, it is possible that these momentous events were also commemorated by the building of a shrine on Via Flaminia that gave its name to the later nucleated centre of Fanum Fortuna.

Hannibal in Southern Italy (207 - 3 BC)

After the defeat of Hasdrubal and his army, Hannibal withdrew to Bruttium. The elections for 206 reflect the joy and relief of the Romans. Two of the three messengers of victory, L. Veturius Philo and Q. Caecilius Metellus, were elected as consuls for 206 BC. This year was memorable only for the fact that it saw the return from Spain of the victorious P. Cornelius Scipio, who was naturally elected as consul for 205 BC. He was given Sicily as his province and embarked on the development of a naval base there in preparation for an invasion of Carthage (as discussed below), while , with P. Licinius Crassus, his consular colleague continued the war against Hannibal in Bruttium.

Mago’s Invasion of Liguria (205 -3 BC)

In 205 BC, as Scipio prepared a naval base on Sicily, Mago, another of Hannibal’s brothers, arrived with an army in a fleet of 30 warships that managed to land, unopposed, at the Roman base at Genua (modern Genoa, on the Ligurian coast). Livy recorded that:

-

“His army grew in numbers every day; the Gauls, drawn by the spell of his name, flocked to him from all parts ... and the Senate was filled with the gravest apprehensions. It seemed as though the joy with which they heard of the destruction of Hasdrubal and his army two years before would be completely stultified by the outbreak of a fresh war in the same quarter, quite as serious as the former one, the only difference being in the commander. They sent orders to [M. Livius Salinator, now proconsul] to move the army of Etruria up to Ariminum ... [another army from Rome was sent] to Arretium”, (‘History of Rome’, 28: 46: 6-9).

The objective was to prevent Mago reaching Hannibal in the south at all costs.

In 204 BC, there was serious unrest in Etruria:

-

“... almost the whole of which had espoused the interest of Mago and had conceived hopes of effecting a revolution through his means. The [new] consul M. Cornelius Cethegus [managed to keep he province] in subjection, not so much by the force of his arms as by the terror of his judicial proceedings. In the trials he had instituted there, in conformity with the decree of the Senate, ... many of the Etruscan nobles who had [made overtures to Mago] ... were condemned ... Others who ... had gone into voluntary exile were condemned in their absence and [their property was confiscated] as a pledge for their punishment”, (‘History of Rome’, 29: 36: 9-12).

Finally, in 203 BC, Cethegus (as proconsul in Cisalpine Gaul) and the praetor P. Quintilius Varus engaged with Mago in Insubrian territory. According to Livy, although the Romans had the better of the fighting, the Carthaginians retreated in good order until Mago was wounded, at which point they abandoned the filed, carrying their wounded commander with them:

-

“As many as 5,000 of the enemy were slain, and 22 military standards captured on that day. Nor did the Romans win a bloodless victory ... The contest would have continued longer, had not the enemy conceded the victory, in consequence of the wound of their general”, (‘History of Rome’, 30: 18: 13-15).

When Mago and his men reached the coast:

-

“... ambassadors from Carthage, who had put into the ... bay a few days before, came to him with directions to cross over into Africa with all speed. They informed him that his brother, Hannibal (who had been sent similar directions), would do likewise, for the affairs of the Carthaginians were not in a condition to admit of their occupying Gaul and Italy with armies”, (‘History of Rome’, 30: 19: 2-3).

The Romans’ counter-invasion of Carthage had succeeded, and the war in Italy was over.

Hannibal’s Defeat in Southern Italy (204-3)

P. Sempronius Tuditanus, Cethegus’ consular colleague in 204 BC, received Bruttium as his province during the conduct of the war against Hannibal. According to Livy:

-

“During this summer, ... [he] was marching near Croton when he fell in with Hannibal. An irregular battle ensued: ... The Romans were repulsed and, although it was more of a melee than a battle, no fewer than 1,200 of the consul's men were killed. [The survivors] retreated in confusion to their camp, but the enemy did not venture to attack it. [Tuditanus], however, marched away in the silence of the night after despatching a message to the proconsul P. Licinius [Crassus]to bring up his legions. With their united forces, the two commanders marched back to meet Hannibal. There was [now] no hesitation on either side ... At the start of the battle, [Tuditanus] vowed a temple to Fortuna Primigenia if he routed the enemy, and his prayer was granted: the Carthaginians were routed and put to flight, and more than 4,000 of them were killed ... Daunted by his failure, Hannibal withdrew to Croton”, ((‘History of Rome’, 29: 36: 4-9)

Tuditanus’ temple was built on the Quirinal, and he finally consecrated it in 194 BC.

Cn. Servilius Caepio and C. Servilius Geminus, were elected as consuls in 203 BC, and both Tuditanus and Cethegus continued as proconsuls. According to Livy, Caepio faced Hannibal:

-

“... in Bruttium, [where he] received the surrender of several places (including Consentia, Aufugium, Bergae, Besidiae, Oriculum, Lymphaeum, Argentanum, and Clampetia) now that they saw that the war was drawing to a close. He also fought a battle with Hannibal in the neighbourhood of Croton, of which no clear account exists. According to Valerius Antias, 5,000 enemy soldiers were killed, but either this is an unblushing fiction, or its omission in the annalists shows great carelessness. At all events, Hannibal did nothing more in Italy, for the delegation summoning him to Africa happened to arrive from Carthage about the same time as the one to Mago”, (‘History of Rome’, 30: 19: 10-2).

Read more:

Clark J., “Triumph in Defeat: Military Loss and the Roman Republic”, (2014) Oxford and New York

Rich J., “The Triumph in the Roman Republic: Frequency, Fluctuation and Policy”, in:

Lange C. and Vervaet F. (editors), “The Roman Republican Triumph: Beyond the Spectacle”, (2014) Rome, at pp. 197-258

Fronda M., “Between Rome and Carthage: Southern Italy during the Second Punic War”, (2010) Cambridge

Pelikan Pittenger M, “Contested Triumphs: Politics, Pageantry and Performance in Livy's Republican Rome”, (2008) Berkeley, Los Angeles and London

Brennan T. C., “The Praetorship in the Roman Republic”, (2000) Oxford

Shackleton Bailey D. R. (translator), “Valerius Maximus: Memorable Doings and Sayings, Vol. I: Books 1-5”, (2000) Cambridge MA

Eckstein A., “Senate and General: Individual Decision-making and Roman Foreign Relations (264-194 BC)”, (1987) Berkeley, Los Angeles and London

Dyson S., “The Creation of the Roman Frontier”, (1985), Princeton, New Jersey

Lazenby J., “Hannibal's War: A Military History of the Second Punic War”, (1978) Warminster

Frank T., “Roman Imperialism”, (1914) New York