Giuseppe Sordini established the original Museo Archeologico in Palazzo della Signoria in 1910. In 1985, it was moved to a surviving wing of the ex-nunnery of Sant’ Agata, on the site of the Roman theatre.

Pre-Roman Spoleto

Finds from Colle Sant' Elia, Spoleto

A number of artefacts from the site of the Rocca di Albornoz, many of which were found during its restoration in 1983-6, reveal that it had been inhabited from a very early date. These include:

-

✴ceramic fragments that date from the middle of the Bronze Age (17th century BC) to the time of the Umbri (7th - 5th centuries BC);

-

✴in particular, a two-handled urn (11th century BC), which was found almost in tact in 2007, is decorated with the heads of birds [made of bronze ?]; and

-

✴a number of small bronze votive statues that provide evidence of one or more sanctuaries here that were in use in the 6th and 5th centuries BC.

Grave Goods from Piazza d’ Armi, Spoleto (7th century BC)

These exhibits came from three successive excavations of the ancient necropolis in Piazza d’ Armi, to the north of the city (see Walk IV):

-

✴A tomb containing bronze grave goods was discovered in 1982.

-

✴A bronze tray on a tripod that would have been used in ritual banquets was found in a ditch grave in 1989.

-

✴Another five tombs were excavated in 2004-5, three of which still contained grave goods:

-

•The reconstruction illustrated here represents a female grave (Tomb 5).

-

•Another female grave (Tomb 6) contained very interesting grave goods, including artefacts used in weaving.

A further 11 tombs were discovered in this area in 2008-9, and there was an article in the paper during my visit in May 2011 that reported the discovery of yet another 30 during the excavations for the construction of a residential complex.

Pre-Roman finds from Outside Spoleto

Grave Goods from Monteleone di Spoleto (6th century BC)

In 1902, a farmer called Isidoro Vannozzi discovered a grave under a field of his farm on Colle del Capitano, outside Monteleone di Spoleto. It contained rich grave goods that a celebrated ceremonial chariot that is now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York. There is a replica of the chariot in the Sala della Biga, Monteleone di Spoleto: it is only open in July - September.

Subsequent excavations of the area have revealed an extensive necropolis that probably belonged to a community that was dispersed along the Nera Valley and that used a series of hill forts in the region, the most important of which was on Colle del Capitano. From this work, it became clear that the necropolis had in fact been in use mainly for cremations since the 12th century BC, with a period of interruption in the 7th century followed by the emergence of mainly inhumation tombs on the site in the 6th century.

These excavations occurred in two phases:

-

✴44 tombs (12th - 6th centuries BC) were found during excavations in 1907, and the associated grave goods were sent to the Museo Archeologico, Florence.

-

✴An opportunity for further excavation arose in the late 1970s when some of the farm buildings were demolished. A further 26 tombs (20 cremation tombs and 6 inhumation tombs) came to light during this and subsequent campaigns.

-

•Grave goods from this phase are mainly in the museum in Spoleto. [Describe the exhibits in the museum]

-

•Other grave goods are Museo Archeologico, Perugia include these late Bronze Age impasto (clay) cinerary urns from tombs 14 and 15.

Votive Offerings from Forma Cavaliera (7th - 3rd century BC)

A number of casual finds over the centuries pointed to the existence of a pre-Roman sanctuary at Forma Cavaliera, Ruscio, near Monteleone di Spoleto. The sanctuary was on the slope of a hill near a stream and might have been associated with the worship of water. A number of votive offerings found during systematic excavation in 1998-9 are displayed in the museum.

Grave Goods from Plestia (6th century BC)

Finds from the Santa Scolastica di Norcia Necropolis

A vast necropolis found was found in the late 19th century on the plain of Santa Scolastica, Norcia. It was in use from the Iron Age to Roman times. A large number of votive bronzes indicate that there was a sanctuary (5th century BC) nearby.

-

✴The grave goods include black painted pottery (4th - 1st centuries BC) from chamber tombs.

-

✴In one of the later tombs (2nd century BC), which was made up of several chambers and had been used for three burials, a large number of fragments were found from the decoration of a carved bone burial couch (in restoration at January 2009).

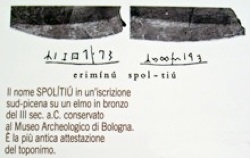

Inscription (early 3rd century BC)

A display in the museum describes this inscription, which is on fragments from a bronze helmet that was discovered in a tomb in the Benacci-Caprara necropolis, Bologna (ani is now in the the Museo Civico Archeologico, Bologna). The inscription, which is written in the South Picene language, reads:

“erimínú spolítiú”

Adriano La Regina (referenced below, at p. 268) dated it to the period 300-250 BC. Daniele Vitale (referenced below at p. 227) recorded that some 77 of the 190 tombs that were discovered here in the 19th century were dateable to the period in which a Gallic tribe known as the Boii were dominant in the area: this period ended when the Romans finally defeated the Boii and established the colony of Bononia (189 BC).

The precise meaning of the inscribed text is unclear, but the second word might refer to the settlement that the Romans called Spoletium: if so, then this would be the only known reference to the pre-Roman settlement. This is, for example, the view of Alberto Calderini (in L. Agostiniani et al., referenced below, at entry 84, p. 91). However, Adriano La Regina (referenced below, at p. 269) suggested that it more probably translates into Italian as ‘Arimino spoliato’ (spoils of war from Ariminium). He suggested that the helmet was probably:

-

“... a votive offering in a sanctuary, following a victory of Sabellic people (probably Picentes) over the Gauls of Ariminum. This would have been the occasion on which it was inscribed. Later, the sanctuary [was presumably] looted during a raid by the Gauls and the helmet ... subsequently reused, which would explain its discovery in the tomb in the Benacci-Caprara necropolis at Bologna”, (my translation).

Roman Spoletium

Cippi of the Lex Spoletina (ca. 240 BC)

These two archaic Latin inscriptions (CIL XI 4766), which were found about 10 km west of the Fonti del Clitunno, bear nearly identical texts:

Honce loucom/ ne qu<i>s uiolatod/ neque exuehito neque

exferto quod louci/ siet neque cedito/ nesei quo die res deina

anua fiet eod die/ quod rei dinai cau[s]a/ [f]iat, sine dolo cedre

[l]icetod, seiquis/ uiolasit Ioue bouid/ piaclum datod

si quis scies/ uiolasit dolo malo/ Iouei bouid piaclum

datod et a(sses) CCC/ moltai suntod

eius piacli/ moltaique dicator[ei]/ exactio est[od]

Michael Gilleland has posted on line two English translations, one of which is as follows:

-

“Let no-one violate this grove nor carry out anything that is in the grove nor set foot in it [or possibly 'cut it'] except annually on the day of the rite; on the day when it is done because of the rite, it shall be permitted to enter (cut) it with impunity. Whosoever violates the grove shall give a purificatory offering of an ox to Jupiter; whoever violates it knowingly and maliciously shall give a purificatory offering of an ox to Jupiter and shall be fined 300 asses [a unit of currency]. The dicator (chief magistrate) shall be responsible for the exaction of the offering and fine”.

The inscription are of great interest in relation to both archaic Latin script and to Roman law. They record the terms of the so-called lex Spoletina, which governed the use of a wood or grove that was sacred to Jupiter, which was presumably located in the area in which the cippi were found.

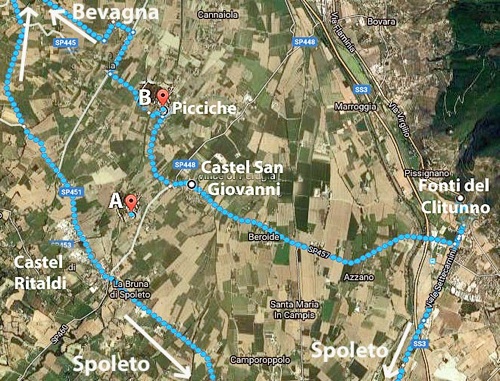

In fact, Giuseppe Sordini found them on two separate occasions and in two separate locations:

-

✴Inscription A was found in 1879 on Colle di San Quirico, between Castel San Giovanni and Castel Ritaldi; and

-

✴Inscription B was found in 1913, embedded in the facade of the church of Santo Stefano in Picciche.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, p. 420) pointed out that Picciche was on a side road off the main Mevania-Spoletium road that crossed the Valle Umbra towards the Fonti del Clitunno. He suggested that:

-

“It is likely that [Inscription B] was originally beside this road, alerting travellers to the fact that they were entering an area that was subject to specific religious constraints; [Inscription A] must have had an analogous function, and its find spot near Castel Ritaldi lends credence to the hypothesis that it was beside the main Mevania-Spoletium. road” (my translation)

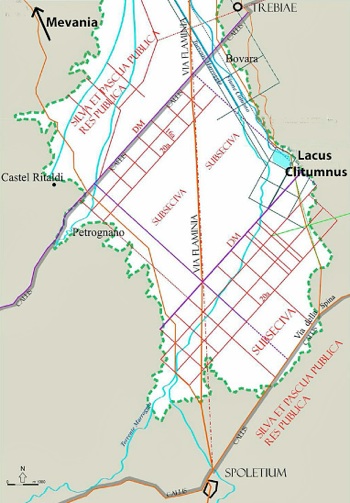

Pertica of Spoletium

Adapted from Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, Figure 3)

According to Luca Donnini (in ‘Screhto Est’, referenced below, entry 75):

-

“Regarding the chronology of the two cippi, based on the script and the language, it certainly seems that both can be securely dated to the years immediately following the deduction of the Latin colony of Spoletium in 241 BC, ...” (my translation)

Paolo Camerieri and Dorica Manconi (referenced below) established the extent of the territory assigned to the colony at this point, as illustrated above: the sacred grove northeast of Castel Ritaldi would have occupied part of the area of public land used for woods and pasture (silva et pascua) across the northwest area of the pertica. (The northern part of this territory (including the Fonti del Clitunno) had probably belonged to Mevania before colonisation.)

Simone Sisani (referenced below, at p. 416) suggested that the grove was sacred to Clitumnus/Jupiter and that the grove might well have extended as far as the sanctuary dedicated to him at the Fonti del Clitunno:

-

✴Vibius Sequester, in his “De fluminibus” (an annotated lists of geographical names, written in the 4th century AD), recorded that:

-

“Clitumnus Umbriae, ubi Iuppiter eodem nomine est”

-

Thus it seems that the river god Clitumnus was, in some sense, a manifestation of Jupiter.

-

✴Propertius, speaking of the god Clitumnus, referred to the Clitumnus river as “his wave” and reported that it was covered (or perhaps shrouded) by “his own woods”.

-

✴Suetonius recorded a visit by the Emperor Caligula to the “river Clitumnus and its nemus (sacred grove)”.

Temples on Colle Sant' Elia (3rd and 2nd centuries BC)

A number of artefacts found on the site of the Rocca di Albornoz suggest that this was the site of the Arx (acropolis) of the Roman colony:

-

✴A number of antefixes and clay votive offerings provide evidence of one or more temples here that were in use in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC.

-

✴One of these fragments came from an antefix (3rd or 2nd century BC) representing “Potnia Theron” (Artemis as Mistress of the Animals), in which the goddess is flanked by rampant panthers.

-

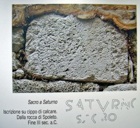

✴A display in the museum describes an inscribed stone cippus that seems to date to the early decades of the Roman colony . The Latin inscription reads “SATURNO SACRO” (sacred to Saturn ). The cippus was found embedded in the wall around the Rocca and would originally have been placed in the ground to mark the limit of the area dedicated to the God. This suggests that the colonists built a temple to Saturn on the lower slopes of Colle Sant' Elia.

-

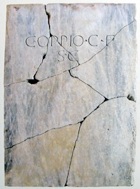

✴This inscription (1st century AD), which is on the base of a statue, commemorates Gaius Oppius, a friend of Julius Caesar. It is likely that the statues of a number of similarly famous men were erected in front of the Roman temples here.

Antefixes from San Nicolò (3rd and 2nd centuries BC)

Finds from San Nicolò include ceramic fragments and terracotta antefixes from a temple. The latter include:

-

✴decorative elements from a frieze;

-

✴a fragment from an antefix representing “Potnia Theron”, similar to that found at the Rocca (see above); and

-

✴a fragment of a young man.

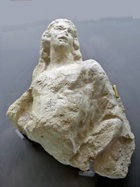

Head of a goddess (2nd century BC)

This head probably came from a full-length statue that stood outside the sanctuary, traces of which survive on the mountain.

Inscription (2nd century BC)

This inscription, which was incorporated into the campanile of the Duomo, records a dedication of something (perhaps a statue or an altar) to Minerva by four officials of the guild of fullers:

-

✴Caius Evulus Stazius;

-

✴Publius Oppius Filonicus;

-

✴Lucius Magnus Alaucus; and

-

✴Panfilus di Turpilius.

Funerary Altar (1st century BC)

Marble Cippi (1st century BC)

Inscription (1st century AD)

This inscription (CIL XI 4819), which was found near the Roman temple erroneously known as ‘the Roman basilica’ reads:

Sex(tus) Volusius Sex(ti) f(ilius) Hor(atia) Melior,

IIIIvir q(uin)q(uennalis), augur, patron(us) municipi,

ob honorem IIIIviratus

Sex(ti) Volusi Noniani, fili sui,

basilicam solo publico a fundamenta

pecunia sua fecit

In this inscription, Sextus Volusius Nonianus commemorated his father, Sextus Volusius Melior, who was a member of the Horatia tribe (that of Spoleto). He was also a quattuorvir quinquennalis, an augur and a patron of the municipium. The basilica that he had financed had presumably stood on a site near the temple mentioned above.

Caius Calvisius Sabinus and Octavian (ca. 40 - 30 BC)

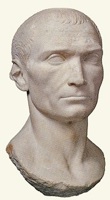

Bust (1st century BC) Inscribed statue base (ca. 31 BC)

probably of C. Calvisius Sabinus commemorating C. Calvisius Sabinus

The bust illustrated above was discovered during the excavation of the Roman theatre in 1954-60. The identity of its subject is unknown, but a good case can be made for Caius Calvisius Sabinus, the subject of the inscription on the statue base that is also illustrated above.

According to Ronald Syme (referenced below, 1939, at p. 221 and note 1), Calvisius was one of only two senators who tried to protect Julius Caesar from his assassins in 44 BC. Thereafter, he became a staunch supporter of the young Octavian, Caesar’s adopted son and heir as he strived to secure his inheritance. Calvisius served as consul of 39 BC, and as the admiral of Octavian’s fleet in 38-7 BC. However, he performed badly during a naval engagement off Sicily against Sextus Pompeius and was replaced in that capacity by Agrippa. According to Appian, Agrippa’s subsequent victory over Sextus Pompeius at the Battle of Naulochus in 36 BC:

-

“... seemed to be the end of the civil dissensions [in Italy]. Octavian was now 28 years of age. Cities joined in placing him among their tutelary gods. At this time, Italy and Rome itself were openly infested with bands of robbers, whose doings were more like barefaced plunder than secret theft. [Gaius Calvisius] Sabinus was chosen by Octavian to correct this disorder. He executed many of the captured brigands, and within one year brought about a condition of absolute security” (‘Civil Wars’, 5:132).

He was proconsul of Hispania in 31-29 BC and is last recorded in an entry in the Fasti Consulares for 28 BC:

-

“Calvisius Sabinus celebrated a triumph from Spain on May 26th, and donated a palm”.

The inscription (CIL XI 4772) in the museum, which came from San Martino in Trignano, some 8 km northwest of Spoleto, reads:

Pietati/ [C(ai)] Calvisi C(ai) f(ilii) Sabini

patroni co(n)s(ulis)

VIIvir(i) epul(onum) cur(ionis) max(imi)

It is inscribed on what was almost certainly the base of a statue of Calvisius Sabinus. It is not certain that he was the consul of 39 BC (he might, for example, have been his eponymous son), but Ronald Syme (referenced below, 1939, at p. 221 and note 1) argued that he was, pointing out that the reference in the inscription to his ‘pietas’ almost certainly refers to his attempt to save Julius Caesar from his fate. The inscription refers to him as a patron, presumably of Spoletium: Ronald Syme, (referenced below, 1964, at pp 113-4) produced circumstantial evidence from other inscriptions from Herculaneum and Cyzicius that Calvius was actually from Spoletium and a member of the Horatia tribe. Emilio Gabba, referenced below, at p. 102) suggested that it was because of this patronage that Spoletium escaped serious retribution after its disloyalty to Octavian during the Perusine War of 41 BC. As well as his consulship, the inscription also records two positions that he held in Rome towards the end of his career:

-

✴septemvir epulones (member of a college of seven men responsible for the organisation of public feasts in Rome); and

-

✴curio maximus (an ancient priesthood).

Since his proconsulate in Hispania is not mentioned, a date of ca. 31 BC for the inscription seems reasonable. It is tempting to suggest that Calvisius had financed the building of the theatre: according to the website of the Soprintendenza dell’ Umbria, its original construction dates to the 1st century BC.

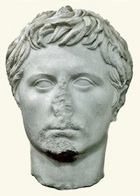

Octavian (ca. 40 BC)

This bust and a similar one at Béziers (now in the Musée Saint-Raymond, Toulouse) are the only known examples of of the so-called ‘Béziers-Spoleto’ group, which Dietrich Boschung (referenced below, at pp. 25-26 and pp. 59-62) dated to 43-40 BC. (A third bust of Octavian that probably belonged to this group, which had been re-cut in ca. 315 AD as a bust of the Emperor Constantine, was discovered during excavations of the basilica forense of Volsinii/Bolsena and is now in the Museo Nazionale Etrusco, Viterbo).

Other Finds from the Roman Theatre

The following artefacts were also found during the excavations of the Roman theatre in 1954-60.

Reliefs from a well

Reliefs

These fragments probably came from reliefs in niches that supported the scena (stage).

-

✴[Relief on the left?]

-

✴The relief on the right probably represented Apollo approaching the seated figure of his father, Jove.

Eros

Young woman (early 1st century AD)

Base of a Statue (ca. 100 AD)

This inscribed column (CIL XI 7872) was found when? where ?? The inscription reads:

[L(ucio) Succonio . f(ilio)---]

[---]r curat(ori) viar(um) [---]

[--- c]ensit(ori) [?Pal?]atiacine[nsium ---]

l(ocus)] d(atus) d(ecreto) d(ecurionum)

[ob merita erga municipes civitat]emque eius [---]

[--- theatru]m(?) pecunia sua r[estituit/refecit? ---]

[--- nomine uxori]s et liberorum suo[rum]

[ex cuius reditu quot(annis) curiae matr]onar(um) et conv[enientium/-ibus? ---]

[--- dedit in publicu]m HS DCLXXXX et d[edit ---]

[VIvir(is) Aug(ustalibus) et compitalib(us) Larum Aug(ustorum) et]

mag(istris) vicor(um) HS CCCCL [---]

[decuriis III scabillar(iorum) vet(eribus)] a scaena HS XXX[---]

[--- no]mine P(ubli) Calvisi(i) Sabi[ni Pomponi Secundi ---]

[No]v(embr-) omnibus anni[s ---] / [---] Maias natali suo [---]

[---]ci Succoniae fi[liae ---]

[--- patronu]m factum municipi[i Spoleti? ---]

[---] Rittiae Pannon[iae --]

Lucius Succonius was one of the Magistri Vicorum [at Spoletium ?], responsible for the census at [Pal ?]atiacinum.

The statue was decreed by the decurions.

He rebuilt the theatre at his own expense.

In the name of his wife and freeborn children, the association of matrons used part of their income each year for donations of:

-

✴690 sesterces to the public [?]

-

✴450 sesterces to the the Seviri Augustalis; the Compitales Lares Augustorum; and the Vicomagistri; and

-

✴a smaller amount to the "scabillares": these were musicians who accompanied themselves on the scabillium, a pair of hinged wooden plates attached to their sandals that they used to beat time, and they belonged to one of the corporations that Lucius Succonius had protected.

It mentions Publius Calvisius Sabinus Pomponius Secundus , who was probably suffect consul in 44 AD

There is a second inscription commemorating Lucius Succonius Priscus in the Museo della Città e del Territorio, Trevi.

Inscription (2nd century AD)

Inscribed gravestone (312 AD)

Until 1854, this gravestone served as a cover for the sarcophagus of St Abbondanza (the virgin) the crypt of San Gregorio Maggiore. The inscription (CIL IX 4787) reads:

D(is) M(anibus) / Florio Baudioni viro ducenario /

protectori ex ordinario leg(ionis) II Ital(icae) /

Divit(ensium) vix(it) an(nis) XL mil(itavit) an(nos) XXV Val(erius)

Vario optio leg(ionis) II Italic(a)e Divit(ensium) /

parenti karissimo / m(emoriam) f(aciendam) c(uravit)

It commemorates Florius Baudioni, a soldier in the Emperor Constantine's army who died, aged 40 during Constantine's march on Rome, having spent 25 years in the army. The gravestone was erected by his kinsman, Valerius Vario. Both men belonged to the II Legione Italica Divitensium, which had its base at modern Deutz, near Cologne.

[See also CIL XI 4085 (Ocriculum), an inscription from the same march: D(is) M(anibus) / Val(erius) Saturnani mil(es) / leg(ionis) II Ital(icae) qui vix(it) / an(nis) XXX mil(itavit) an(nis) XIII /5 co(ho)r(tis) VI / Val(erius) Laupicius fratri / karissimo /m(emoriam) f(aciendam) c(uravit).]

Double-sided Inscription

This double-sided inscription, [which is now in the Deposit of the Museum ??], apparently came from the Tempietto del Clitunno.

-

✴The earlier inscription (CIL XI 4815, probably 2nd century AD) reads:

-

C(aius) Torasius C(ai) f(ilius) Hor(atia) Severus IIIIvir i(ure) d(icundo) augur

-

suo et P(ubli) Mecloni Proculi Torasiani pontif(icis)

-

fili(i) sui nomine loco et pecunia sua fecit (*) idem

-

ad celebrandum natalem fili(i) sui in publicum dedit HS CCL(milia)

-

ex quorum reditu III K(alendas) Sept(embres) omnibus annis decuriones in publico

-

cenarent et municipes praesentes acciperent aeris octonos item

-

dedit VIviris Aug(ustalibus) et compit(alibus) Larum Aug(ustorum) et mag(istrorum) vicorum HS CXX(milia) ut ex reditu

-

eius summae eodem die in publico vescerentur hunc ob merita eius

-

erga rem publicam ordo decurionum patronum municipi(i) adoptavit

-

It records that Gaius Torasius Severus, son of Gaius, of the Horatia tribe, quattuorvir with judicial power, augur, in his own name and in that of his son Publius Meclonius Proculus Torasianus, the pontiff, erected something at his own expense. He also gave 250,000 sesterces to the city and 120,000 sesterces to the Seviri Augustalis,the Compitales Lares Augustorum and the Magistri Vicorum, sums that were to be invested in order to finance a public banquet on his son’s birthday Because of his merits, the city council adopted Gaius Torasius Severus as the city’s patron.

-

✴The later inscription ((CIL XI 4781, ca. 360 AD)

-

Reparatores orbis adque urbium rest/tutores

-

dd[omini] nn[ostri] Fl[avius] Iul[ius] Constantinus, P[ius] F[elix]

-

semper Aug[ustus]

-

et Iulianus nobilissimusac victoriosissimus Caes[or]

-

ad aeternamdivini nominis propagationem/ thermas Spoletenis

-

in praeteritium igne consump/tas

-

sua largitate restituerunt

-

It records the restoration of the baths at Spoleto by the Emperor Constantius II (Flavius Julius Constantius) and his co-ruler as caesar, the future Emperor Julian the Apostate.

It seems likely that the earlier inscription related to the original construction of these baths. Later references in a letter of King Theoderic (493-526) confirm this hypothesis:

-

✴A letter addressed to the Deacon Elpidius gave him permission to pull down a portico behind the Baths of Torasius and to build a new edifice (perhaps a church) on the site, provided that the building to be demolished (which he had been told was “covered with the squalor of age”) was of no public utility.

-

✴A letter from Theoderic addressed to Faustus, the Praetorian Prefect, probably refers to the his largesse in relation to these baths: “As our Kingdom and revenues prosper, we wish to increase our liberality. Let your Magnificence therefore give to the citizens of Spoletium another "millena" [an amount of money] for extraordinary gratuitous admissions to the baths. We wish to pay freely for anything that tends to the health of our citizens, because the praise of our times is the celebration of the joys of the people.”

Read more:

S. Sisani, “I Rapporti tra Mevania e Hispellum nel Quadro del Paesaggio Sacro della Valle Umbra”,, in

G. Della Fina (Ed.), “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, (2012) Orvieto (pp. 409-64)

L. Agostiniani et al. (Eds), “Screhto Est: Lingua e Scrittura degli Antichi Umbri”, (2011) Città di Castello

P. Cameriere and D. Manconi, “Le Centuriazioni della Valle Umbra da Spoleto a Perugia”, Bollettino di Archeolgic Online, (2010) 15-39

A. La Regina, “Il Guerriero di Capestrano e le Iscrizioni Paleosabelliche”, in

L. Franchi dell’ Orto (Ed.), “Pinna Vestinorum e il Popolo dei Vestini”, (2010) Rome

D. Vitale, “Bononia/ Bologna”, in:

J. T. Koch (Ed.), “Celtic Culture: Volume I”, (2006) Santa Barbara, Ca., at pp. 226-8

D. Boschung, “Die Bildnisse des Augustus”, (1993) Berlin

E. Gabba, “Trasformazioni Politiche e Socio-Economiche dell' Umbria dopo il 'Bellum Perusinum'”, in:

G. Catanzaro and F. Santucci (Eds), “Bimillenario della Morte di Properzio”, (1986) Assisi pp. 95-104

R. Syme, “Senators, Tribes and Towns”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 13: 1 (1964) 105-25

R. Syme, “The Roman Revolution” (1939,latest edition 2002) Oxford

Return to Museums in Spoleto.

Return to Walk I.