Maximinus, Augustus Maximus (311-2 AD)

Maxentius in Rome (311-2 AD)

Maxentius and the Gens Valeria

Home Cities History Art Hagiography Contact

Maximinus, Augustus Maximus (311-2 AD): Main Page

Maximinus, Augustus Maximus (311-2 AD)

Maxentius in Rome (311-2 AD)

Maxentius and the Gens Valeria

Home Cities History Art Hagiography Contact

Maximinus, Augustus Maximus (311-2 AD): Main Page

Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius had inherited the family name Valerius from Diocletian, via his father, Maximian. In effect, it was the Tetrarchs’ family name. Thus, after his break with Maximian, Maxentius might have attempted to put a different, and probably a more Roman, gloss on his name by asserting an implied descent from the renowned Republican, Publius Valerius Publicola.

However, as I set out below, the evidence for this is less firm than is sometimes suggested. In these sections, I develop my hypothesis that Maxentius’ putative descent from the ancient gens Valeria formed an important part of his propaganda only during the last few months of his reign.

Publius Valerius Publicola

Publius Valerius Publicola the founder of the gens Valeria, was long-remembered in Rome as one of the first two Consuls of the Republic (in 509 BC). Despite his service in expelling the hated Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last of the Kings of Rome, he had shortly thereafter found himself the object of criticism. Thus, according to Plutarch:

“Valerius was living in a very splendid house on the so‑called Velia. It hung high over the Forum, commanded a view of all that passed there, and was surrounded by steep [ground] and hard to get at, so that when he came down from it the spectacle was a lofty one and the pomp of his procession worthy of a king. ... [However], when he heard from his friends, who spared him no detail, that he was thought by the multitude to be transgressing, he ... quickly got together a large force of workmen and ... tore the house down, and razed it all to the ground. .. Valerius was received into the houses of his friends until the people [who were suitably mortified by his reaction] gave him a site and built him a house of more modest dimensions than the one he had lived in before, where now stands the temple of Vica Pota .... [Because of his humility, the Romans] therefore called him Publicola, a name that signifies people-cherisher” (‘Life of Publicola, 10:1).

Livy was quite specific about the site of this house, in a passage that he attributed to Publicola himself:

“ ‘I will not only bring down my house into the plain, but I will build it beneath the [Velia], so that you [i.e. his detractors] may dwell above me, a suspected citizen ...’ Immediately all the materials were brought down to the foot of the Velian mount, and the house was built at the foot of the hill where the temple of Victory now stands (‘History of Rome’, 2:7).

Equally importantly, early sources describe how the gens Valeria had acquired the rare privilege of intramural burial on a site next to Publicola’s domus:

✴“Publius Valerius, surnamed Publicola, fell sick and died .... A sure and incontestable proof of the frugality he had shown during his whole lifetime was the poverty that was revealed after his death. For, in his whole estate, he did not leave enough even to provide for his funeral and... his relations were intending to carry his body out of the city in a shabby manner ... to be burned and buried. The Senate, however, learning how impoverished they were, decreed that the expenses of his burial should be defrayed from the public treasury, and appointed a place in the city near the Forum, at the foot of the Velia, where his body was burned and buried, an honour paid to him alone of all the illustrious men down to my time” (Dionysius of Halicarnassus, ‘Roman Antiquities’ 5:48:3).

✴“[Publius Valerius Publicola] was ... by express vote of the citizens, buried within the city, near the so‑called Velia, and all his family were given the privilege of burial there. Now, however, [i.e. by the late 1st century AD] none of the family is actually buried there, but the body is carried thither and set down, and someone takes a burning torch and holds it under the bier for an instant, and then takes it away, attesting by this act that the deceased retains the right of burial there but relinquishes the honour. After this, the body is borne away” (Plutarch, ‘Life of Publicola 23).

Hans Beck (referenced below, at p 363) pointed out that:

“... the tradition of Valerius’ house rests on multiple anachronistic assumptions. The notion of a public home, granted to a Consul in 509 BC at the motion of the Roman people, has no claim to historical authenticity. [However,] this does not mean that the house of Valerius Publicola was pure fantasy. The domus Poplicolae was a prominent realm of memory of the late Republic, with a well-established location in the urban topography of Rome. It was situated sub Veliis, at the foot of the Velia ...”

He elaborated (at note 10):

“The exact location [of the domus and the adjacent sepulchre] is difficult to determine. The majority of sources place the house sub Veliis. ...

-the inscription CIL VI 1327, (P. Valesius Valesi f. Poplicola) has been discovered in this area of the Velia; as well as

-an elogium for the Valerii Messallae (CIL VI 31618), which may have been part of the house and grave ensemble.”

According to the compiler of the ‘Eagle’ catalogue, the inscription CIL VI 1327, which no longer survives, probably dated to the period 27 BC-14 AD. ‘Valesius’ was clearly an error for Valerius, and the inscription commemorated Publicola himself, presumably having been commissioned by a proud descendant. The second inscription (50 BC), which survives in the Musei Capitolini, commemorates:

✴Marcus Valerius Messalla Niger (the Consul of 61 BC), son of Marcus and grandson of Manius ; and

✴Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus (the Consul of 31 BC), son of Marcus (above) and grandson of Marcus.

Maxentius and the Gens Valeria

The sections below address the circumstantial evidence provided by Maxentius’ public works and by his coinage that might support the hypothesis that he claimed descent from the ancient gens Valeria.

Basilica Nova

The huge basilica nova, which Maxentius built on the Sacra Via, as discussed in my page on Maxentius' Public Works. This location at the foot of the Velia (above) was similar to that given by the literary sourced (above) as site of the house and sepulchre of Publicola . The discovery of inscriptions relating to the gens Valeria (above) on a site behind the basilica in the 19th century reinforced the perception of this association. Thus, for example:

✴Rodolfo Lanciani (referenced below), who recorded the discovery of CIL VI 3826 (above) in the Via del Tempio della Pace (behind the basilica Nova) in the 19th century, suggested (at p. 49) that:

“The inscription probably belonged originally to the sepulchre of the gens Valeria, which [according to literary sources] was not far from the Forum, under the Velia. Now, this location well-corresponds with the position of the basilica nova: and it is quite natural to suppose that Maxentius, having cleared the pre-existing buildings from the area in order to make way for it, had taken advantage of those materials [including this inscription] that could be put to alternative use” (my translation).

✴Giuseppe Lugli (referenced below, at p. 168) asserted that:

“The location of the house of the Valerii is fixed with some precision by the fragment of a large travertine base with an elegiac inscription [CIL VI 3826] for two members of the family, which was found near the [basilica nova]” (my translation).

Fabiola Fraioli (referenced below, at p 298) was specific that Maxentius had chosen this site for his basilica specifically because of its association with the gens Valeria:

“[Maxentius’] choice of the site for the construction of [the basilica Nova] should be considered in relation to the desire of the Emperor, whose own gentilicum was Valerius, to be associated with the celebrated gens of the early Republic, who owned a house and sepulchre sub Velia.”

In the context of this assertion, Fabiola Fraioli cited the entries by Filippo Coarelli in the ‘Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae’ for:

-the ‘Basilica Constantiniana, B. Nova’, I (1993) 171; and

-the ‘Domus : P. Valerius Publicola’, II (1995) 209-10.

I have not been able to consult these directly, but John Curran (referenced below, at pp 58-9) referenced the first in his account of this Maxentian project:

“The choice of the Velia [for the site of the basilica nova] was no accident. According to Coarelli, Maxentius was tapping into some of the most ancient traditions of the city. The most celebrated member of the gens Valeria, P. Valerius Publicola, had long been associated with the Velia, near the Temple of the Penates: ‘and thus in a point on the hill that seems to correspond to the western apse of the basilica’ where the huge statue of Maxentius stood.”

(The phrase in italics is my translation of a direct quote by John Curran from Filippo Coarelli’s first entry above).

However, there is no direct evidence that Maxentius chose this site for primarily for this dynastic reason. Indeed, construction might well have started before his break with Maximian (in April 308 AD), at thus a time when his Herculian affiliation was still in place. It is mre likely that the choice of location was essentially opportunistic, since the existing buildings here might well have been destroyed in the fire that damaged the nearby Temple of Venus and Roma in 307 AD. In addition:

✴The proximity of the site to the Temple of Venus and Roma offered a significant aesthetic and iconographic opportunity: as John Curran (referenced below, at p. 58) observed:

“The alignment of the basilica so carefully with the Temple of Venus and Roma suggests a connection between these buildings that was at the very least aesthetic. But the juxtaposition of the cella of Roma [the west cella of the temple] and Maxentius’ basilica may have [had] a special significance.”

✴On a more mundane note, the restoration of that temple must have involved a large team of architects and builders and huge stores of building materials. It may well have been convenient to employ these resources additionally on the construction of the basilica on this nearby site.

Maxentius’ Consecration Coins

IMP MAXENTIUS, DIVO MAXIMIANO,

DIVO MAXIMIANO PATRI/ PATRI MAXENTIUS AUGUSTUS/

AETERNAE MEMORIAE AETERNAE MEMORIAE

RIC VI Rome 251 RIC VI Rome 244

Mats Cullhed (referenced below, at p 78) summarised the message of the consecration coins that Maxentius issued in 311 AD (discussed in my page on Maxentius' Consecration Coins (311 AD)) for (inter alia) the Emperors Maximian (examples of which are illustrated above), Galerius and Constantius:

“[These Emperors] belonged to the same gens Valeria. ... By this display of pietas, Maxentius behaved as became [their] heirs ... Implicitly, in this way, [he] claimed ... the power that had been theirs. ... The supreme imperial power [now] resided with the Roman representative of the Valerian family.”

It has to be said, however, that there is little numismatic support for the idea that Maxentius laid particular stress on the fact that his was a Valerian imperial dynasty:

✴Maxentius himself rarely appeared as a Valerian on his coins, the exceptions being three gold multiples (RIC VI Rome 167, 172 and 173) with the obverse legend IMP C M VAL MAXENTIVS P F AVG), which he issued in the late summer or early autumn of 307 AD (i.e. before his break with Maximian); and

✴none of the consecration coins above identified the deceased as a member of the gens Valeria.

Nevertheless, as discussed below, it is possible:

✴that the funerary structure on the reverses of the consecration coins above (and on those of the other coins in this series, which were minted for divus Romulus) represented the Maxentian rotunda on the Sacra Via;

✴that this structure stood on the presumed site of the sepulchre of Publicola; and

✴that it appeared on the coins because it was devoted to the veneration of their consecrated subjects, the deified members of the gens Valeria.

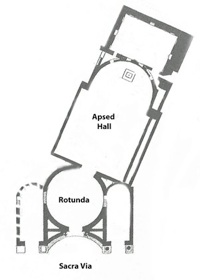

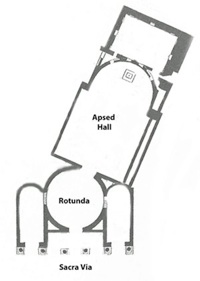

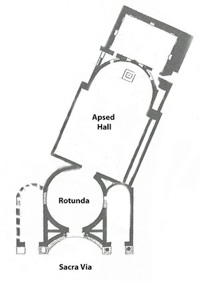

Rotunda on the Sacra Via

Licia Luschi (referenced below) linked this interesting Maxentian building (discussed in my page on Maxentius' Rotunda on the Sacra Via) to the gens Valeria. I have not been able to consult this work directly, but Thomas Bayet (referenced below, at at p 75) recorded that:

“... according to Luschi’s analysis, the rotunda should be seen as the ‘Templum gentis Valeriae’, a sanctuary in honour of the gens Valeria, the [putative] ancestors of Maxentius and the Tetrarchs” (my translation).

Naja Regina Armstrong (referenced below, at pp 244-5) gave another useful précis of Luschi’s hypothesis:

“... Luschi suggests that the rotunda acted as a dynastic temple to the divi of Maxentius’ family [i.e. the gens Valeria]. Prominent since the Republic ... the gens Valeria had gained special privileges, including the licence to bury within the city walls. Maxentius, who used family connections to legitimise his power, may have revived this tradition with a dynastic monument near the site of his ancestor’s historic domus and tomb.”

She concluded (at p. 246) that:

“Based on the evidence available, it is likely that the rotunda depicted on [the reverses of] Maxentius’ [consecration] coins [above) is equivalent to the [rotunda and its side aisles]. Moreover, the coins’ symbolism suggests that [this edifice] served a commemorative function. Luschi’s hypothesis of a temple to the gens Valeria is the most direct means Maxentius could have chosen to honour his deceased relatives. ... such a monument accords best with Maxentius’ desire [evidenced by these coins] to tie his rule to [consecrated] members of his gens.”

Rotunda Complex

Original flat facade (my suggestion) Final concave facade

IMP MAXENTIUS, DIVO MAXIMIANO,

DIVO MAXIMIANO PATRI/ PATRI MAXENTIUS AUGUSTUS/

AETERNAE MEMORIAE (hexastyle reverse) AETERNAE MEMORIAE (tetrastyle reverse)

RIC VI Rome 251 RIC VI Rome 244

It is important to stress that many scholars deny that the rotunda complex: (a) ever functioned as a shrine or temple; and (b) was represented on this second series of ‘AETERNAE MEMORIAE’ coins. However, as I set out in my more detailed pages, I think that Licia Luschi and Naja Regina Armstrong are essentially correct. Specifically, I think that the hexastyle and tetrastyle reverses of these coins (examples of which are illustrated above in coins minted for divus Maximianus) represented the rotunda and its side aisles in its two phases of construction:

✴the hexastyle reverses probably represented the initial plan, when the façade of the rotunda was flat (with the two undocumented central columns of the actual structure shown here as part of my proposed reconstruction); and

✴the tetrastyle reverses represented the structure after the change of plan that led to the concave façade of the rotunda, which was unobscured by columns.

While, if correct, this hypothesis links the second series of ‘AETERNAE MEMORIAE’ coins to the rotunda, it remains to discuss its link to the gens Valeria. As suggested by Naja Regina Armstrong (above), this link arises from the description by Dionysius of Halicarnassus (above) of the place where Publicola was buried:

“The Senate, however, learning how impoverished [Publicola’s family] were, decreed that the expenses of his burial should be defrayed from the public treasury, and appointed a place in the city near the Forum, at the foot of the Velia, where his body was burned and buried, an honour paid to him alone of all the illustrious men down to my time” (‘Roman Antiquities’ 5:48:3).

Thus, it is entirely possible that the rotunda (which stands beside the basilica Nova, nearer to the Forum) was built on the presumed site of sepulchre of Publicola.

I would like to put forward a more specific suggestion, which arises for Plutarch’s account of how this site was used by the gens Valeria in his day (late 1st century AD):

“[Publius Valerius Publicola] was ... by express vote of the citizens, buried within the city, near the so‑called Velia, and all his family were given privilege of burial there. Now, however, none of the family is actually buried there, but the body is carried thither and set down, and someone takes a burning torch and holds it under the bier for an instant, and then takes it away, attesting by this act that the deceased retains the right of burial there but relinquishes the honour. After this, the body is borne away” (‘Life of Publicola 23).

I wonder whether the late decision to change the façade of the rotunda from flat to concave arose out of a desire on the part of Maxentius to articulate a circular space in front of it in a manner appropriate for the place where the bodies of members of the gens Valeria were ceremonially set down before burial. Specifically (as discussed in my page on Maxentius' Rotunda on the Sacra Via):

✴I think that it is entirely possible that Maxentius initially conceived of the rotunda as a vestibule that cleverly allowed the hall behind it, which had stopped short of the Sacra Via and was oriented at 22° to it, to be harmonised with the new urban environment that had been created by the completion of the adjacent basilica Nova.

✴I further think that the planned function of the rotunda complex changed in 311 AD, in order to capitalise on the dynastic opportunities that arose after the death of Galerius (in April/May of that year) and the putative consecration processes that followed it. It was probably at this point that the apsed space behind the rotunda was called into service for the veneration of Maxentius’ consecrated relations, Maximian, Galerius, Constantius and Romulus.

✴Finally (as noted above), I think that the subsequent change to the rotunda façade, which was reflected in the change in the designs of the reverses of the consecration coins, arose from Maxentius’ desire to designate a circular space in front of the rotunda as the place where the bodies of members of the gens Valeria were ceremonially set down before burial, in honour of Publicola.

If this is correct, then Maxentius’ claims to be a descendant of Publicola became important only in the last few months of his reign. I suggest below that this might well have been at the suggestion of Aradius Rufinus, who served as one of the Consuls designated by Maxentius for September-December 311 AD and as Urban Prefect from 9th February until 27th October 312 AD.

Aradius Rufinus

So far, the proposed link between Maxentius and the ancient gens Valeria has been put forward purely on the basis that his rotunda and possibly the adjacent basilica nova were built on the site of Publicola’s sepulchre and domus. However, another link between Maxentius and the gens Valeria is provided by Aradius Rufinus, whom Maxentius appointed as:

✴Consul for September-December 311 AD; and

✴Urban Prefect from 9th February of the following year, a post from which Maxentius removed him on the eve of his fateful battle against Constantine (28th October 312 AD).

Aradius Rufinus was almost certainly the father of two men who were commemorated by a number of inscriptions that were found in the 16th century in the gardens of San Stefano Rotondo on the Caelian hill:

✴Lucius Aradius Valerius Proculus (CIL VI 1690, LSA-1396; CIL VI 1691, LSA-1397; CIL VI 1692; LSA-1398 and CIL VI 1693 LSA-1399); and

✴Quintus Aradius Valerius Proculus (CIL VI 1684-9).

The find spot had long been the site of one of the houses of the gens Valeria: according to John Matthews (referenced below):

“[Avianus] Symmachus, addressing Lucius Aradius Valerius Proculus, signo Populonius [in ca. 375 AD, in one of a series of epigrams addressing “the good men of [his] age”], ... praised his friend for his descent from the Republican Poplicolae; but by this time, the house [on the Caelian] where, in the 3rd century, Lucius Valerius Poplicola Balbinus Maximus had been honoured by his clients, had passed by marriage to the Aradii - a new family of the Empire, who perhaps came from Africa.”

Since Aradius Rufinus did not use the gentilicum Valerius, it was presumably he who had married into the gens Valeria, thereby achieving this impressive lineage for his sons.

The replacement of Aradius Rufinus as Urban Prefect on the eve of the battle suggests that Maxentius smelled treachery, a suspicion that was probably vindicated when he was given the same post by Constantine only a month after his victory. Avianius Symmachus chose to touch on this aspect of his career in an epigram in the series mentioned above:

“Loved by all, protector of the fearful:

-to the good leaders of [his] time [like Constantine], [Aradius Rufinus] skilfully applied the spur; and

-to the tyrants [like Maxentius, he applied] the bit” ((Ep. 1:2:3).

The distinction made here between the bit and the spur is surely diplomatic hindsight: Aradius had clearly enjoyed a position of trust with both Maxentius and Constantine and, at least in the case of Maxentius, this trust might have been misplaced.

Of particular interest here is the fact that Lucius Aradius Valerius Proculus (probably his oldest son) went on to have a brilliant career under Constantine, whose high esteem for him is confirmed by a letter (ca. 336-7 AD, recorded in an inscription, CIL VI 40776, LSA-2685 in the Forum of Trajan) in which he commended Proculus to the Senate. The key part of this letter for the present discussion is as follows:

“Recalling the distinguished nobility of the ancestry of Proculus ... and the virtues acknowledged in the private and public performance of his services, conscript fathers, it is easy to value just how much glory [he] … received from his ancestors ...”

We know from the inscriptions above from the family home on the Caelian that Proculus held four Roman priesthoods:

✴three traditional ones for men of his class:

•augur;

•pontifex maior; and

•membership of another college of priests, the quindecemviro sacris faciundis; and

✴the post of pontifex Flavialis, a priest (perhaps the high priest) of the imperial cult of Constantine’s gens Flavia.

This suggests to me the following hypotheses:

✴that, during his time as Consul and then Urban Prefect (i.e. from about September 311 AD, in the period in which he probably issued the consecration coins mentioned above), Aradius Rufinus’ services to Maxentius included advice on the development of the cult of his deified relations, centred on the rotunda complex; and

✴that he and his son subsequently delivered a similar service to Constantine, in relation to the imperial cult of his gens Flavia (as discussed in more detail - on which page).

Read more:

F. Fraioli, “Regione IV: Templum Pacis”, in

A. Carandini, “Atlante di Roma Antica”, (2012) Rome: Vol. 1 pp 281-306; and Vol. 2, Maps 89-106 inclusive

H. Beck, “From Poplicola to Augustus: Senatorial Houses in Roman Political Culture”, Phoenix 63 (2009) 361-84

N. Armstrong, “Round Temples in Roman Architecture of the Republic through the Late Antique Period”, (2001) Thesis of University of Oxford

M. Cullhed, “Conservator Urbis Suae: Studies in the Politics and Propaganda of the Emperor Maxentius” (1994) Stockholm

T. Bayet, “Architectura Numismatica: Iconographie Monétaire du Temple de Rome, des Mausolées et des Ouvrages Fortifiés au Bas-Empire”, Revue BeIge de Numismatique, 139 (1993) 59-81

L. Luschi, “Iconografia dell' Edificio Romano nella Monetazione Massenziana e il "Mastino del Divo Romolo", Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, 89 (1984) 41-54

J. Matthews, “Continuity in a Roman Family: The Rufii Festi of Volsinii”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 16:4 (September 1967) 484-509

G. Lugli, “Monumenti Minori del Foro Romano”, (1947) Rome

R. Lanciani and W. Henzen, “Elogio di M. Valerio Messalla”, Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, (1876) 48-60

Maximinus, Augustus Maximus (311-2 AD)

Maxentius in Rome: (311-2 AD) Maxentius' Consecration Coins (311 AD)

Maxentius' Rotunda on the Sacra Via Maxentius and the Gens Valeria

Literary Sources: Diocletian to Constantine (285-337 AD)

Return to the History Index