Arco di Augusto: with an inscription ‘Augusta Perusia’

As described in the previous page, the old municipium of Perusia had survived the Perusine War (41-40 BC), albeit that it suffered terrible destruction and lost much of its extra-urban territory. Initially, it continued to be administered by quattuorviri . However, at some time after 27 BC (when the triumvir Octavian became the Emperor Augustus), it was renamed Augusta Perusia. This change of status was commemorated by inscriptions on the city’s ancient gates: three of these inscriptions survive:

-

✴on Arco Etrusco, also known as Arco di Augusto (CIL XI 1929:1);

-

✴on Porta Marzia (CIL XI 1930:1); and

-

✴on Porta della Mandorla (CIL XI 1931b, now fragmentary).

The EAGLE database (see the CIL links) dates these inscriptions to the period 1-14 AD.

When the city was reconstituted as Augusta Perusia, its quattuorviri were replaced by duoviri. On many occasions, this change in magistracy accompanied colonisation. However, as Simone Sisani (referenced below, at 288) pointed out, the funerary inscription (CIL XI 1941, 70-100 AD) of the duovir Gaius Betuus Cilo (discussed below) designates him as ‘patrono municipi’. He therefore concluded that the new title and the new administrative structure constituted an act of re-foundation: an analogous case is evidenced at the old Etruscan city of Veii, which had been abandoned in the 1st century BC and re-founded by Augustus as the municipium Augustum Veiens.

Two Early Duoviri

Two surviving inscriptions, both of which are dated by the EAGLE database (see the CIL links below) to the period 1-14 AD, commemorate men who had held the posts of quattuorvir and duovir during their careers:

-

✴The inscription (CIL XI 1943) on an urn that was found in the nunnery of Santa Lucia, which is now in the entrance cloister in the Museo Archeologico, reads:

L(ucius) Proculeius A(uili) f(illius)

Titia gnatus

IIIIvir IIvir

-

It commemorates Lucius Proculeius, son of Aulus and Titia.

-

-

-

-

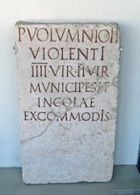

✴A dedicatory inscription (CIL XI 1944) that was preserved in the nunnery of San Francesco delle Donne until 1815, when it was moved to the Museo Archeologico, reads:

P. VOLUMNIO P. F.

VIOLENTI

IIIIVIR IIVIR

MUNICIPES ET

INCOLAE

EX COMMODIS

-

This dedication, probably of a statue, was made by the citizens and inhabitants of the municipium to Publius Volumnius Violenti, son of Publius. (He was a member of the ancient Etruscan family who had traditionally been buried in the Ipogeo dei Volumni outside Perusia.

Cult of Augustus

These four travertine cippi on the south wall of the entrance cloister in the Museo Archeologico all contain the same Latin inscription (CIL XI 1923):

Augusto sacr(um)/ Perusia restituta

Consecrated to Augustus by Perusia “restored”

All four are damaged and one of them was adapted at some point to serve as a fountain. They were first documented in the 16th century, by which time they seem to have been embedded in the Etruscan walls below the church of SS Annunziata, and they had probably been erected on a site outside the walls here. An altar (now lost) that was found in a similar location in the 16th century had an inscription (CIL XI 1922):

Augusto/ lucus/ sacer

This grove is sacred to Augustus

This suggests that the cippi and the altar came from a cult site dedicated to Augustus here, and that the cippi were probably used to mark the boundaries of the grove.

The inscriptions on the altars refer to ‘Perusia restituta’: Simone Sisami (referenced below, at p. 290) suggested that they were erected to celebrate the city’s return to the good graces of Augustus as Augusta Perusia. It is significant that the grove was sacred to Augustus, rather than to divus Augustus: as Sisani pointed out, this presumably implies a cult offered to Augustus before his death in 14 AD. Further, since the earliest securely-attested cult to Augustus dates 2 BC, Sisani suggested that:

-

“... we might reasonably date the cippi [and the altar] to the period after 2 BC and [thus] to the last 15 years of Augustus’ reign ...” (my translation)

Urban Development

The epigraphic evidence discussed above suggests that Perusia only began to emerge from the ashes of the Perusine War in the last 15 years of Augustus’ reign. However, there is little evidence of any physical recovery of the urban fabric at this time. The exception might be evidenced by a fragemntary inscription (AE 1991, 666) that was discovered in 1899 in piazza IV Novembre (the site of the Roman forum) and is now in the deposit of the Museo Archeologico. Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, at p. 31 and Figures 6a and b) completed the inscription as follows:

Imp(eratori) Cae[sari divi f(ilio) Augusto]

Perusini [municipes Augustani]

Ti(berio) Claud[io Ti(beri) f(ilio) Neroni]/ c[onditoribus]

She suggested that it

-

✴related to a monument that the citizens of Augusta Perusia had dedicated to Augustus in the name of his stepson, Tiberius; and

-

✴dated to the period after 6 BC, when Tiberius was first recognised as Augustus’ designated successor and 4 AD,when Augustus adopted him (leading to a change of name that made no reference to his biological father, Tiberius Claudius Nerone).

Simone Sisani (referenced below, at p. 293), who gave a slightly different completion but broadly the same dating, suggested that the monument in question was a theatre in Piazza Piccinino (although the only evidence for such a monument is the semi-circular form of the piazza).

S. Sisani, “Perusia Restituta”, Bollettino della Deputazione di Storia Patria per l’Umbria, 108:1 (2011) 273-94

Later Imperial Period

Relatively little survives of Perusia Augusta.

-

✴Benedetto Bonfigli's fresco of the siege of Totila's Perugia (1454) in the Cappella dei Priori shows his soldiers camped outside the Porta Marzia in an amphitheatre that dates to the 1st century AD, and remains of it have been excavated under the nearby Palazzo della Penna.

-

✴The Duomo seems to have been built on the site of a temple that stood in the forum of the Augustan city, at the junction of its two main thoroughfares.

-

✴The walls recently discovered in Via Cantine and those incorporated into the façade of the Duomo to the right under the Loggia di Braccio probably once formed part of an inner circuit that protected the forum and acropolis.

-

✴A mosaic from ca. 50 AD is displayed in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, and another from the 2nd century AD can be seen in Via Elisabetta.

Betuus Cilo, Praetor Etruriae XV Populorum

A now-lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 1941) from the base of a funerary monument from an unknown location in Perugia reads:

C. Betuo C.f. Tro(mentina)

Ciloni Minuciano

Valenti Antonio

Celeri P. Liguvio

Rufino Liguviano

aedili, IIvir(o) quinq(uennali)

sacerdoti III lucorum, pr(aetori)

[Etr]uriae XV populorum

patrono municipi

Betua Respectilla fil(ia) / patri piissimo

L(ocus) d(atus) d(ecreto) d(ecurionium)

This commemorated Gaius Betuus Cilo, a man who had clearly enjoyed a successful, albeit provincial career in public office, holding the following posts in Perusia before becoming Praetor Etruriae XV Populorum (an elected priest of the Revived Etruscan Federation):

-

✴aedile;

-

✴duovir quinquennial; and

-

✴priest of three groves that were sacred to Augusts (see above).

He was also designated as a patron of Perusia. His monument had been erected by his daughter, Betua Respectilla, on land donated by the decurions. The EAGLE database (see the CIL link) dates the inscription to the period 70-100 AD.

Cilo’s full name was extremely long:

Gaius Betuus Cilo Minucianus

Valens Antonius Celer Publius Liguvius Rufinus Liguvianus

He probably had a familial connection with Betuus Cilo, who was executed in Gaul by the Emperor Galba in 68 AD:

-

✴Mario Torelli suggested that, given his entirely provincial career, he had probably been an ancestor of the man executed in Gaul, who had moved in more exalted circles.

-

✴However, Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, at p. 77) suggested that the execution in Gaul would have dented the family’s career prospects, and that the man buried at Perugia, might have been his adopted son. On this basis, she dated the inscription to the late 1st century AD.

Early Christianity

According to tradition, St Constantius was Bishop of Perugia in the 2nd century. His ability to perform miracles aroused the ire of the authorities and he was imprisoned at Perugia and then at Spello before being beheaded at Spoleto in 178. His body was recovered and buried at the site of the present church of San Costanzo outside Porta San Pietro. (St Costantius became a patron saint of Perugia in 1310, and his relics were apparently discovered in San Costanzo in 1781).

Perugia formally became a diocese in the second half of the 5th century. The church of Sant’ Angelo belongs to this period.

The first securely attested bishop of Perugia, Maximianus, was documented at Roman synods in 49, 501 and 502.

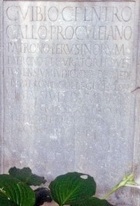

Gens Vibia

Gaius Vibius Gallus Proculeianus (205 AD)

C. Vibio C.f. L.n. Tro(mentina)

Gallo Proculeiano

patrono Perusinorum

patrono et curatori r(ei) p(ublicae)

Vet/tonensium, iudici de V dec(uriis)

aedi/li, patrono collegi centon(ariorum)

Vibius Veldumnianus

avo karissimo, ob cuius

dedicationem dedit

decurionibus ((denarios)) II, plebi ((denarium)) I

L(ocus) d(atus) d(ecreto) d(ecurionum)

This inscription commemorates Gaius Vibius Gallus Proculeianus, the great-grandfather of the future Emperor Vibius Trebonianus Gallus (see below). The statue of him that once stood on this base was commissioned by his own “dearest grandfather”, Vibius Veldumnianus. He had been a patron, decurial judge and aedile in Perusia and patron of the Collegia Centonariorum (guilds of textile dealers); and also “patronus et curator rei publicae Vettonensium” (defender of the interests of the citizens of Vettona at Rome and treasurer (curator) on behalf of the Roman authorities).

Vibius Thallus (230-50 AD)

An now-lost inscription (CIL XI 1927) from an unknown location in Perusia commemorated Afinia Gemina Baebiana, the wife of Vibius Gallus (both of senatorial rank. It was dedicated by their client Vibius Thallus, who was almost certainly a freedman of the family. The EAGLE database (see the CIL link) dates it to the period 230 - 51 AD.

Emperor Vibius Trebonianus Gallus (251-3 AD)

Gaius Vibius Trebonianus Gallus, who belonged to a Perusian family that attained senatorial rank in the 3rd century, served as suffect consul in ca. 245 AD and was then appointed by the Emperor Decius as governor of Moesia Superior. When Decius was killed there in a war against the Goths in 251 AD, the army acclaimed Trebonius Gallus as emperor. He adopted Decius; surviving son, and named him co-emperor, while he named his own son, Gaius Vibius Volusianus Augustus as Caesar. Decius’ son died shortl afterm following which Volusianus become co-emperor.

During another Gothic war in Moesia in 253, the army acclaimed their commanded, Marcus Aemilius Aemilianus Augustus as emperor. He marched on Rome, and defeated Trebonianus Gallus and Volusianus in a battle near Interamna Nahars. They fled and were murdered by their own guards at Forum Flaminii.

At some time during his short reign, Trebonianus Gallus gave Perusia the honorary title "Colonia Vibia", an event commemorated , an event that was commemorated by inscriptions on three of the city’s ancient gates:

-

✴Arco Etrusco (CIL XI 1929:2);

-

✴Porta Marzia (CIL XI 1930:2); and

-

✴Porta della Mandorla (CIL XI 1931a, now fragmentary).