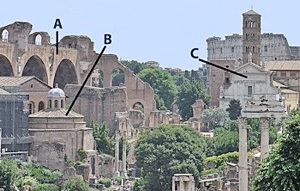

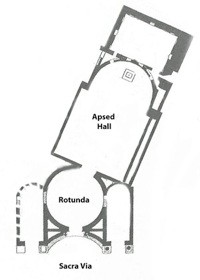

So-called Forum of Maxentius on the Via Sacra, at the foot of the Velia

(A) Basilica Nova; (B) Rotunda on Via Sacra;

(C) Site of Temple of Venus and Roma (now the church of Santa Francesca Romana)

Maxentius claimed the goddess Roma, who personified the special qualities of the Senate and the people of Rome, as his auctor imperii (the source of his legitimacy as Augustus): following his break with his father, Maximian, in April 308 AD, she was his only such source (as described in the main page on Maxentius in Rome (308-11 AD)). For their part, the Romans seem to have been gratified to have an Emperor who was proud of his Romanitas and who was resident in the city. This was the central theme of the seminal publication of Mats Cullhed (referenced below, 1994), which he entitled “Conservator Urbis Suae” (preserver of his city), a phrase that Maxentius himself had used on many of his coins. Cullhed’s Chapter 3, which he also entitled “Conservator Urbis Suae”, dealt with:

-

“... one prominent trait in the propaganda of Maxentius: his appearance as the champion of Rome and the guardian of its traditions”.

Cullhed used the numismatic evidence to establish his model of Maxentius’ self-proclaimed Romanitas. He then applied this model to the major monuments that can be attributed to him, concluding (at p 60) that:

-

“Taken together, they are an overwhelming statement of the attitude adopted by Maxentius: he wishes to guarantee that the traditions, the position and the privileges of the city of Rome will be preserved”.

More recent scholarship has developed Cullhed’s insights, including his use of public works as one way of demonstrating not only his respect for Rome and its traditions but also the benefits that Rome and its citizens received from his residence there. For example:

-

✴Elizabeth Marlowe (referenced below, 2010, at p. 201), who described how Constantine dealt with Maxentius’ architectural legacy after his victory in 312 AD, asserted that:

-

“Much of the modern historiography has followed Constantinian propagandists like Eusebius, and painted Maxentius as a persecutor of Christians and a cruel, illegitimate despot. But some recent scholarship has emphasised how deftly Maxentius manipulated Rome’s wounded pride over the long absences of the imperial court. Indeed, Maxentius seems to have made the flattery and restoration of Rome the central theme of his regime. ... To back up [his claim to be the preserver of his city], he sponsored a series of splendid new buildings in the manner of the great architectural benefactors of the 1st and 2nd centuries, an imperial practice that had lapsed in the intervening centuries”.

-

✴John Fabiano (referenced below, at p. 110) concluded that:

-

“Maxentius’ entire political programme promised Rome’s renovatio ... and he carried it out across multiple mediums in a coordinated manner. None were more potent and conspicuous than his building initiatives. Maxentius ubiquitously fashioned himself as the Conservator Urbis Suae and, in carrying through all that this appellation signified, he shattered the flawed belief that Rome was defunct and that its power now resided in Emperors, carried to where they resided. To the contrary, Maxentius proved that the eternal city was a living, breathing manifestation of years of imperial dominance and that it had the power, if harnessed and manipulated correctly, to create and uphold Emperors. Maxentius answered the call from Rome for an Emperor to return and he turned Tetrarchic ideology [i.e. the belief the ‘Rome’ was wherever the Emperor resided] upside down, something not lost on Constantine when he entered the city after his triumphant victory on October 28, 312 AD.”

Forum of Maxentius

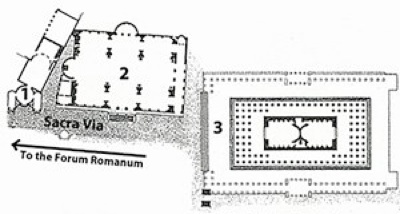

So-called Forum of Maxentius on the Sacra Via

(1) Rotunda (2) Basilica Nova (3) Templum Romae (Temple of Venus and Roma)

Adapted from Figure 8 of Cullhed (1994), referenced below

Much of Maxentius’ building activity centred on the Sacra Via, an ancient road that ran westwards from the Temple of Venus and Roma to the Forum. Such was the strength of the Maxentian associations of this area after its renovation that Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, 1986) dubbed it the ‘Forum of Maxentius’. This area probably had resonance for Maxentius because:

-

✴it contained the Temple of Venus and Roma, the traditional locus for the celebration of the cult of Roma (as discussed below); and

-

✴it was also associated with Publicola, reputedly one of the first Consuls of Rome (in 509 BC), whose domus and sepulchre (as described in the literary sources) had stood near the Forum, on the lower slopes of the Velia (i.e. on the north of the Sacara Via), a site that well-described that of Maxentius’ rotunda (labelled (1) in the plan above and described below).

Temple of Venus and Roma

This photograph shows the surviving remains of this huge double temple (looking towards the Sacra Via and the Forum beyond). The Emperor Hadrian, who famously designed the temple himself, erected it on the site of the vestibule of Nero's infamous palace (later known as the Domus Aurea), and numismatic evidence suggests that it was completed by his successor, Antoninus Pius, in 141 AD. Thorsten Opper (referenced below, at p 126) stressed the importance of this project:

-

“By far the largest building in ... Rome, the Temple of Venus and Roma, with its associated cult and festival, was intended [by Hadrian] as the focus of a new state ceremonial reflecting Rome’s origins and glorious achievements”.

The temple had two back-to-back cellae, one for each of its cult statues, which represented:

-

✴Roma Aeterna, the genius or personification of the city, in the cella facing the Forum Romanum; and

-

✴Veneris Felicis, a variant of the cult of Venus that Hadrian introduced into the city, which stood in the cella facing Flavian amphitheatre (now called the Coliseum, which was behind the photographer in the illustration above).

Roma Aeterna had long been associated with the imperial cult in the provinces. As Duncan Fishwick (referenced below, at page 313) explained, Hadrian now introduced this cult to Rome itself:

-

“Hadrian’s attachment to Roma is shown by the new festival of Natalis Urbis, which he substituted in 121 AD for the old Parilia [an ancient festival of the start of Spring, which had long been held on the 21st April, the anniversary of the foundation of the city]. Roma joined the official pantheon for the first time ... : her cult was served in the capital by a new college of duodecimviri [the duodecimviri urbis romae] and in the provinces by sacerdotes. The propagation of the new cult was further served by the great temple of Roma and Venus, begun by Hadrian perhaps as early as 121 AD, although not officially consecrated until 136/7 AD”.

According to Elizabeth Marlowe (referenced below, 2010, at note 8) the cult remained of great importance into the 4th century:

-

“Inscriptions show that all the men who held [the office of duodecimviri urbis romae] were Senators ... In the later 4th century, the title was embraced by the leading participants in the ‘pagan’ Kulturkampf of that era”.

Maxentius’ association with the temple is also illustrated by the fact that its restoration was included among his achievements in the short imperial biographies included in the so-called ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’, in much the same way as Hadrian’s original construction was recorded there:

“While [Hadrian] was ruling, the templum Romae et Veneris was built”.

“While [Maxentius] was ruling, the templum Romae burned down and was rebuilt”.

Scholars usually assume that the fire that destroyed the temple occurred in 307 AD, and that Maxentius’ coins celebrated its subsequent rebuilding or restoration. It has to be said that a large number of Emperors and would-be Emperors had depicted the temple on coins, simply as a means of conveying their Romanitas. Donald Brown (referenced below, at Appendix A) listed these issues, starting (unsurprisingly) with Hadrian, but extending throughout the 2nd and 3rd centuries and into the early 4th century, when even the usurper in Africa, Domitius Alexander used the design and the legend ‘ROMAE AETERNAE’ on two issues minted at Carthage (RIC VI 70 and 75). However, Philip Hill ( referenced below, at p 16-7) pointed out that:

-

“Since all the coins on which [a cult statue of] the goddess appears after 307 AD show her holding a globe [instead of the Palladium, as had been usual in the previous century], it may well be that Maxentius had to furnish the rebuilt temple with new cult statues.”

This seems to me to provide circumstantial evidence for his assertion (at p. 16) that the fire had indeed occurred in 307 AD, shortly after Maxentius’ coup.

RIC VI Rome 202a (307-8 AD)

Maxentius frequently celebrated the temple on his coins, beginning with those that he minted early 307 AD, for himself and also for Maximian and Constantine (with whom he was then allied). Each of these coins commemorated its subject as “CONSERV VRB SVAE” or variants thereof: Maxentius and his allies cared, above all, for ‘their’ city of Rome as symbolised by this, its most important temple.

The restoration of the temple was a massive undertaking, and Maxentius doubtlessly burnished his ‘Roman credentials’ very significantly in the process. The result was extremely impressive: thus, Elisha Ann Dumser (referenced below, at p. 281), who carried out a detailed analysis of the archeological record, concluded that:

-

“The exterior [of the temple] was ... preserved in all its [original] magnificence .... [while] the interior conformed to a confident new vision, one in keeping with early 4th century tastes for colour, dynamism and sophisticated volumes.”

John Fabiano (referenced below, at p. 94) concluded that:

-

“The massive 165 x 100 meter terrace, with its retained porticoes, ... the 112 column dipteral peristyle temple that sat atop it, ... [and] the audaciously redesigned cellae, [were combined in a renovated structure that] announced Maxentius to the Eternal City and served as a means to fulfil his promise to the populus Romanus. Maxentius turned what could have been a disastrous omen caused by an untimely fire [soon after his coup] into an opportunity to secure his power in the Urbs. By virtue of its position and scale, the Templum Romae would serve as the visual introduction and conclusion to Maxentius’ redeveloped Sacra Via depending on one’s direction of travel] and, with this one building, Maxentius highlighted his dedication to Rome; it was the exceptional reminder of his Romanitas.”

Basilica Nova

The huge basilica on the Sacra Via, next to the Temple of Venus and Roma was included under Regio IV in the list of the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’ (see below), designated therein as:

-

✴the ‘basilica nova’, in the version entitled Curiosum urbis Romae regionum XIV; and

-

✴the ‘basilica Constantiniana’ in the other surviving version, which is known as the Notitia urbis Romae regionum XIV.

The existence of two names for the basilica probably reflects Aurelius Victor’s account that:

-

“[The Senate dedicated all] the monuments that he [Maxentius] had built in a magnificent manner - the city’s sanctuary and basilica (urbis fanum atque basilicam) - to Flavius [Constantine after his victory of 312 AD] ...” (‘De Caesaribus’ 40:26).

Thus, it seems likely that the new Maxentian basilica (the ‘basilica nova’) was subsequently re-dedicated to Constantine, when it became the ‘basilica Constantiniana’.

The section in the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’ on the reign of the Emperor Domitian (81-96 AD) recorded the previous use of the site:

-

“While he [Domitian] was ruling many public works were carried out: .... the horrea piperataria (pepper warehouses) where now is the basilica Constantiniana ... ”

The commercial buildings here might well have been destroyed in the fire that damaged the nearby Temple of Venus and Roma in 307 AD. It has been argued that Maxentius chose this site because of its connections to the gens Valeria, and thus its dynastic significance (as discussed in my page on Maxentius and the gens Valeria,) However, construction might well have started before Maxentius’ break with Maximian (in April 308 AD), when this consideration would not of been particularly relevant. Thus, the decision is more likely have been taken primarily because the damage caused by the fire had rendered it available. In addition:

-

✴The proximity of the site to the Temple of Venus and Roma offered a significant aesthetic and iconographic opportunity: as John Curran (referenced below, at p. 58) observed:

-

“The alignment of the basilica so carefully with the Temple of Venus and Roma suggests a connection between these buildings that was at the very least aesthetic. But the juxtaposition of the cella of Roma [the west cella of the temple] and Maxentius’ basilica may have [had] a special significance.”

-

✴On a more mundane note, the restoration of that temple must have involved a large team of architects and builders and huge stores of building materials. It may well have been convenient to employ these resources additionally on the construction of the basilica on this nearby site.

Following a detailed architectural analysis, John Fabiano (referenced below, at p 88) concluded:

-

“From the outset Maxentius planned to create a massive architectural structure, ornately adorned and highly conspicuous. .... Its design, [which was] more akin to thermal architecture [than to the architecture of other civic basilicas in Rome], was innovative and deftly negotiated the space between:

-

✴his Sacra Via rotunda and the Templum Pacis (Flavian Temple of Peace) to the west; and

-

✴the Templum Romae [Temple of Venus and Roma, above] to the east.

He intended a monumental entrance from the [Sacra Via] and included a subsidiary entrance on the east side, such that the building [also communicated with] the western facade of the Templum Romae, while its massive interior space, elongated nave, and western apse all bespeak a building intended for civic purposes.”

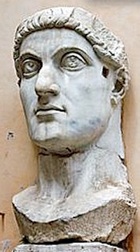

Fragments of a colossal statue of Constantine were found in the area of the basilica in 1486 (and are now the major attraction in in the courtyard of the

Palazzo dei Conservatori of the

Musei Capitolini). They included the iconic head and neck (illustrated here), which measure some 3 meters in height. The discovery of a plinth in the west apse of the basilica suggests that this was the statue’s original location, and two surviving drawings show that it was certainly there in the 16th century.

-

✴Eric Varner (2004 and 2014, referenced below) used sculptural analysis to demonstrate that this face had been recut in ca. 312-5 AD from a likenesses of Maxentius that had in turn probably been recut from a likenesses of Hadrian.

-

✴Architectural analysis by Elisha Ann Dumser (referenced below, at p. 87) found support for this from the fact that the statue and the western apse of the Maxentian basilica seem to have been designed for each other.

Note however that some scholars disagree: for example, Gregor Kalas (referenced below, at p 68) insisted that:

-

“Since the colossal portrait of Constantine was probably re-carved from Hadrian’s image and not [from that of] Maxentius, there is little reason to think that the original [i.e. Maxentian] basilica had contained a mammoth portrait”.

The left breast of the statue and part of the left shoulder and arm, which were discovered in 1951, indicate that the figure of Maxentius/ Constantine was enthroned, with his upper torso bare. His right arm was raised, and he held a sceptre in his right hand, an iconography that would have associated him with Jupiter Optimus Maximus. Elisha Ann Dumser (referenced below, at p 90) spelled out the message that the statue would have carried:

-

“The assimilation with the king of the gods elevates Maxentius to divine status, as well as granting him the visual role [that was] assigned under the Tetrarchy to the senior, ‘Jovian’ Augustus [i.e. Diocletian]”.

One could go further: the execution of the likeness of Maxentius probably post-dated 308 AD, when Maxentius had become estranged from his father, Maximian Herculius. With this iconography in this prominent public arena, Maxentius was perhaps now proclaiming himself as the direct successor of (the retired) Diocletian.

The size and architectural form of the Basilica Nova and its location close to the Forum Romanum all suggest that it was a major civic building. Indeed, Aurelius Victor’s reference to the “city’s ... basilica”, if it did refer to the basilica nova (as seems likely), arguably placed it at the heart of the civic administration of Rome. Fabiola Fraioli (referenced below, at p. 298) noted its vicinity to other structures that she argued were probably associated with the Urban Prefectura:

-

✴Two inscriptions (CIL VI 37114 and 31959) that were found to the north east of the basilica (near the church of San Pietro in Vincoli), which commemorated Junius Valerius Bellicius, the Urban Prefect in of 421-3 AD, recorded his restoration of parts of this administrative complex:

-

•the portico;

-

•the scriniis (archives);

-

•the secretarium Tellurense (a space used for secret interrogation, with the modifier “Tellurense” implying a location in or near the Temple of Tellus);

-

•the tribunalia (law courts); and

-

•the Urbana sedis (headquarters).

-

✴The inscribed base of a statue (CIL VI 1696, LSA-1401) commemorating Attius Insteius Tertullus, the Urban Prefect of 307-8 AD was found near a domus behind its north apse. Fraioli suggested that this domus was the official residence of the holder of this office.

The proposed locations of these parts of the complex are indicated in the publication containing Fraioli’s work (referenced below, in Volume 2, Map 20).

While it is generally accepted that the basilica nova was a civic basilica, some scholars doubt that it should be associated specifically with the Urban Prefectura. Thus for example, Elisha Ann Dumser (referenced below, at p. 113) asserted that:

-

“Serving Rome as a grand civic basilica - not the judicial hall of the Urban Prefect - the basilica nova may have stood unchanged well into the 4th century.”

However, others accept this association:

-

✴Robert Chenault (referenced below, at p. 16) was particularly specific, asserting that it was:

-

“... probably intended to be an audience hall for the Urban Prefect, whose offices were in this same area.”

-

✴John Curran (referenced below, at p. 58) was of the same opinion:

-

“[The basilica] was a prestigious architectural statement in support of the city’s administration. It should not be forgotten that Maxentius was particularly anxious to associate the Prefects of the City closely with his own régime. ”

If this is correct:

-

✴its construction would have been entirely consistent with the prominence that Maxentius gave to the Urban Prefects, who chaired meeting of the Senate and who generally held the post at the peak of a successful Senatorial career; and

-

✴it certainly would have provided an ideal place in which they could broadcast imperial decrees or make other important announcements, under the watchful eye of the colossal imperial statue in the west apse.

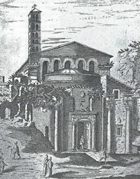

Rotunda on the Sacra Via

This lovely domed rotunda immediately to the west of the basilica nova has long attracted scholarly attention, in part because of its interesting architecture and good state of preservation but also because of the heated debate that has long surrounded its original function (discussed in my page on Maxentius' Rotunda on the Sacra Via). It was once flanked by two narrow, apsed side halls (of which, only traces survive), which had formed an integral part of the original construction project. Each aisle protruded into the Sacra Via and was articulated by a pair of cippolino columns raised on plinths (of which, only the pair on the right survives). Its intriguing concave façade (discussed below), which linked the main portal to the façades of each of the protruding side halls, was decorated with two columnar niches on each side that presumably housed statues. (Unfortunately, only the lower part of this facade survives, and even this is partially obscured by later masonry). The portal itself comprises a pair of re-used bronze doors flanked by two porphyry columns. These support a richly decorated marble architrave that had also come from an earlier building.

The ‘Liber Pontificalis’, in its account of the life of Pope Felix IV (526‑530), recorded that:

-

“hic fecit basilicam sanctorum Cosmae et Damiani in urbe Roma, in loco qui appellatur via sacra, iuxta templum urbis Romae.”

Thus, Felix IV built a church dedicated as SS Cosma e Damiano in the Sacra Via, next to the ‘templum urbis Romae’ (which has been variously identified as the rotunda, the basilica nova or the Temple of Venus and Roma). What is not in doubt is that this church was established in the hall behind the rotunda, and that the rotunda itself thereafter formed its vestibule (as shown in this engraving of 1569 by Étienne Dupérac, in which one of the columns on the left was still standing).

Today, the rotunda communicates with what is now the crypt of SS Cosma e Damiano. Its interior can be viewed through glass inserted into the back wall of the church above. It is also sometimes open for exhibitions.

Re-cutting of ‘Nero’s Colossus’

The sculptor Zenodorus famously carved a colossal statue for the vestibule of Nero's Domus Aurea. According to Pliny the Elder,

-

“In consequence, however, of the public detestation of Nero's crimes, this statue was consecrated to the Sun” (‘Natural History’, 34:18)

The Emperor Hadrian had it moved to the nearby site of the Flavian amphitheater (usually referred to as the Colosseum) to make way for the Temple of Venus and Roma (above). It was last documented in this location in the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’, under Regio IV, where it is described by the compiler of the page as:

-

“The colossal statue, 102 feet high. On its head are 7 rays each 22 feet long”.

Three fragments of an inscription, which were discovered in the mid-1980s in the attic of the Arch of Constantine, seem to have come from the base of this statue. Although the text is unpublished, Elizabeth Marlowe (2006, referenced below, at pp 228-9 and note 34) assembled all of the published works that relate to it. She summarised:

-

“The text apparently mentions a Col[ossum] and its re-dedication to divus Romulus ... by Lucius Cornelius Fortunatianus, a governor of Sardinia at the time. The extraordinary scale of the letters is such that the panels could only have been located on a base proportionate to a colossal statue. Presumably, this new inscription was installed on the base of the old Colossus of Sol in conjunction with its (otherwise unattested) re-dedication under Maxentius. .... After Constantine's defeat of Maxentius in 312 AD, the dedicatory inscription was removed from the colossus (and no doubt replaced) and buried in the attic of the new Emperor's victory monument [the so-called Arch of Constantine]”.

Elizabeth Marlowe then touched on the later history of the statue:

-

“To summarize, we know that both Maxentius and Constantine altered the dedicatory inscription of the Colossus of Sol:

-

-[Maxentius] installed panels rededicating the monument to his son; and

-

-[Constantine] had them removed.

-

These acts may have taken place in conjunction with the alteration of the statue's portrait features by one or both emperors. [i.e. If Maxentius had indeed had the face recut to represent Romulus, Constantine would have either replaced it with his own image or returned it to a representation of Sol]. In this regard, Constantine behaved much like [earlier Emperors who had adapted the statue and/or its inscription to meet their dynastic needs]. But Constantine's appropriation of the monument also took an additional and highly novel form. By installing his triumphal arch directly in front of it, he literally transformed the way spectators saw the statue”.

Forum Romanum

Adlocutio Frieze, Arch of Constantine (315 AD)

While the area on the Velia (above) seems to have provided Maxentius with a blank canvas on which he could express himself in architectural terms, the more important Forum Romanum arguably offered more restricted opportunities. According to the so-called ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’, the area, which had been devastated by fire in the reign of Carinus, had been substantially rebuilt under the Tetrarchs:

-

-“While [Carinus and Numerian] were ruling, there was a great famine [in Rome] and public buildings burned down: the Senate; the Forum of Caesar; the Basilica Julia and the Graecostadium”.

-

-“While [Domitian and Maximian] were ruling many public works were (re)built: the Senate, the Forum of Caesar, the Basilica Julia, the stage of the Theatre of Pompey, two porticos, three nymphaea, two temples, [including ??] the temple of Isis and Serapis, the Arcus Novus [the now-lost Arch of Diocletian on Via Lata], and the baths of Diocletian”.

Much of the renovation seems to have been undertaken ahead of the celebration of the vicennalia of Diocletian in 303 AD. For example, the frieze illustrated above depicts Constantine giving a speech from the Rostra in 312 AD, with a five-columned monument behind him that had been erected for the celebration of Diocletian’s vicennalia. Excavations in ca. 1980 revealed that this five-columned monument had been part of a larger project:

-

✴a matching five-columned monument had also been built at this time at the opposite end of the Forum, in front of the Temple of Divus Iulius; and

-

✴seven more free-standing columns had been erected in front of the Basilica Iulia to the south.

Thus, it seemed that the central area of the forum had been enclosed on three sides by columnar screens at this time.

Southern Colonnade (??)

Elizabeth Marlowe (forthcoming, referenced below) has shown that the extended 17-column monument discussed above was probably built in two stages. As she explained:

-

“It seems more likely to me that [either]:

-

-the monument built in 303 AD comprised three legs of 5 columns each, and that two additional columns were added to the southern leg later; or (even more plausibly)

-

-the original monument consisted only of the two 5-column segments on the eastern and western Rostra, [while] the entire third [southern] leg was added at a later date”.

She suggested that this later date might well have fallen during the reign of Maxentius, who:

-

“... sought to legitimize his usurpation through association with the Tetrarchy.”

She further suggested two occasions on which this putative Maxentian intervention might have occurred:

-

“[during the] brief period in 307-8 AD when [Maximian had come out of retirement and] Maxentius and Constantine were allies, minting coins for one another and erecting statues of each other in their respective capitals”; or

-

“after the death of [Maxentius’] son Romulus, [when] he sought to establish a ‘Valerian dynasty’ and began issuing coins not only for his son but for some of the deceased members of the first Tetrarchy”.

Thus the candidates for the last two of the figures atop the seven southern columns would have been:

-

✴Maxentius and Constantine, if the intervention dated to 306-7 AD; or

-

✴Maxentius and Romulus, if it post-dated 309 AD [or, indeed, at any time after April 308 AD, when Maximian left Rome and Maxentius named Romulus as his fellow-Consul].

Statues of Mars and Maxentius

Two statue bases which had originally been inscribed in the 2nd century AD seem to have been re-used by Maxentius for statues that were placed near the Lapis Niger, a black stone in front of the Senate House that was believed to mark the tomb of the founder Romulus. (These statue bases are discussed in detail by John Fabiano (referenced below), at pp 55-62). The name of Maxentius was erased from both inscriptions, presumably after his defeat in 312 AD:

-

✴The inscription (CIL VI 33856, LSA-1388) on one of these bases read:

MARTI INVICTO PATRI/ ET AETERNAE URBIS SUAE

CONDITORIBUS

DOMINUS NOSTER/ IMP(erator) [MAXENTIUS P(ius) F(elix)]

INVICTUS AUG(ustus)

To unconquered Mars, the father

and the founders of his own eternal City [Romulus and Remus]

our lord, the Emperor Maxentius, pious, fortunate, unconquered Augustus

-

Another inscription on the right side of this base records that the statue was dedicated on the 21st April (the anniversary of the founding of the city) in an unidentified year by Furius Octavianus, who held clarissimus rank and was the ‘curator of the sacred temples’.

-

✴The inscription (CIL VI 1220, LSA-1387) on a second statue base that was re-used in the nearby Basilica Julia read:

CENSURAE VETERIS / PIETATISQUE SINGULARIS

DOMINO NOSTRO /[MAXENTIO].

To him of old-fashioned austerity and exceptional piety

our lord Maxentius ...

-

The bottom of the base is missing so the identity of the dedicator(s) is unknown. John Fabiano (referenced below, at note 140) suggested that the dedicators had been the Senate and the people of Rome. (John Fabiano also puts forward the translation of ‘censura’ as ‘austerity’, at pp 58-9, which I have followed).

With reference to the first inscription, Maxentius’ association with Mars perhaps implies a date after Maxentius’ break with his Herculean father. Robert Chenault (referenced below) also suggested that the inscription implied a parallel between:

-

✴Mars, the father of Romulus and Remus; and

-

✴Maxentius, the father of Romulus, who might also have had his second son at this time.

It is thus tempting to date the inscription to the period between Maximian’s flight from Rome in April 308 AD and the death of Romulus in the following year.

These statues obviously need to be considered in the context of the surrounding Tetrarchic columnar monuments discussed above. It seems likely that Maxentius sought to make a number of favourable comparisons that would enhance his standing with the Romans. Thus, in these statues and their inscriptions, he stressed

-

✴his allegiance to Rome and its founding deities; and

-

✴his possession of qualities traditionally valued by the Romans.

Maxentius was presumably portrayed in a manner that was immediately recognisable to the Romans because he lived among them. In contrast, the Tetrarchs were probably portrayed on their columns in the usual indistinguishable fashion that marked their ‘concordia’. Maxentius would, of course, would have been present in Rome on the festival of Natalis Urbis, when at least the first of the statues was dedicated. This too was in sharp contrast to the traditional absence of the Tetrarchs.

Read more:

‘RIC VI’ - see Sutherland (1967) below

E. Marlowe, “The Multivalence of Memory: the Tetrarchs, the Senate, and the Vicennalia Monument in the Roman Forum” in:

K. Galinsky and K. Lapatin, (Eds.), “Cultural Memories in the Roman Empire”, (forthcoming in 2015), Getty Museum Press

I am extremely grateful to Dr Marlowe for sending me an advance copy of this important paper.

G. Kalas, “The Restoration of the Roman Forum in Late Antiquity: Transforming Public Space”, (2015) Texas

E. Varner, “Maxentius, Constantine, and Hadrian: Images and the Expropriation of Imperial Identity“ in

S. Birk, T. Kristensen and B. Poulsen (Eds.) “Using Images in Late Antiquity’ (2014) Oxford

J. Fabiano, “Roma, Auctrix Imperii? Rome's Role in Imperial Propaganda and Policy from 293 CE until 324 CE”, (2013) Thesis of University of Toronto

F. Fraioli, “Regione IV: Templum Pacis”, in

A. Carandini, “Atlante di Roma Antica”, (2012) Rome: Vol. 1 pp 281-306; and Vol. 2, Maps 89-106 inclusive

T. Opper, “Hadrian: Empire and Conflict”, (2010) Harvard

E. Marlowe, “Liberator Urbis Suae: Constantine and the Ghost of Maxentius” in

B. C. Ewald and C. F. Noreňa (eds.) “The Emperor and Rome: Space, Representation and Ritual’ (2010) Yale

R. Chenault, “Rome Without Emperors: The Revival of a Senatorial City in the Fourth Century CE”, (2008) Thesis of the University of Michigan

F. Coarelli, translation into English of a number of his works on the topography of ancient Rome, as:

J. Clauss and D. Harman, “Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide”, (2007, 2nd edition 2014) Oakland, California

E. Marlowe, “Framing the Sun: The Arch of Constantine and the Roman Cityscape”, Art Bulletin, 88:2 (2006) 223–42

E. Dumser, "The Architecture of Maxentius: A Study in Architectural Design and Urban Planning in Early 4th Century Rome" (2005), Dissertation of University of Pennsylvania

E. Varner, “Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture“ (20o4) Leiden, pp 217 and 287

N. Armstrong, “Round Temples in Roman Architecture of the Republic through the Late Antique Period”, (2001) Thesis of University of Oxford

P. Tucci, "Nuove Acquisizioni sulla Basilica dei Santi Cosma e Damiano", Studi Romani, 49 (2001) 275–93

J. Curran, “Pagan City and Christian Capital: Rome in the Fourth Century”, (2000) Oxford

M. Cullhed, “Conservator Urbis Suae: Studies in the Politics and Propaganda of the Emperor Maxentius” (1994) Stockholm

C. E. V. Nixon and B. S. Rodgers, “In Praise of Later Roman Emperors: The Panegyrici Latini”, (1994) Berkeley

D. Fishwick, “Imperial Cult in the Latin West, Volume I: Studies in the Ruler Cult of the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire” (1993) Leiden

P. Hill, “The Monuments of Ancient Rome as Coin Types”, (1989) London

F. Coarelli, “L’ Urbs e il Suburbio”, in

A. Giardina (Ed.), “Societa Romana e Impero Tardoantico” (1986) Rome, pp 19-20

L. Luschi, “Iconografia dell' Edificio Romano nella Monetazione Massenziana e il ‘Tempio del Divo Romolo’”, Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, 89 (1984) 41-54

C. H. V. Sutherland, “Roman Imperial Coinage: Volume VI: From Diocletian’s Reform to the Death of Maximinus (294-313 AD)”, (1967, reprinted 1973) London

D. Brown, “Temples of Rome as Coin Types”, (1940) New York

P. Whitehead, “The Church of SS Cosma e Damiano in Rome”, American Journal of Archaeology, 31:1 (1927) 1‑18.

R. Lanciani, “The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome: a Companion Book for Students and Travelers”, (1897)

L. Canina, “Gli Edifici di Roma Antica e sua Campagna” (1848) Rome

Galerius as Augustus II (308-11 AD) Licinius (308-11 AD)

Maxentius in Rome: (308-11 AD) Maxentius' Public Works

Maxentius' Complex on Via Appia Maxentius' Coins for Divus Romulus (309 AD)

Constantine in Gaul (308-11 AD) Constantine, Divus Claudius and Sol Invictus

Consecrated Tetrarchs (306-11 AD) Consecrated Tetrarchs: Mausoleum Coins

Literary Sources : Diocletian to Constantine (285-337 AD)

Return to the History Index