Sources for Via Amerina

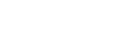

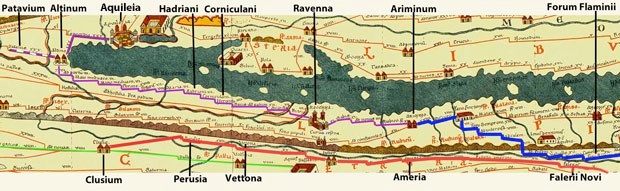

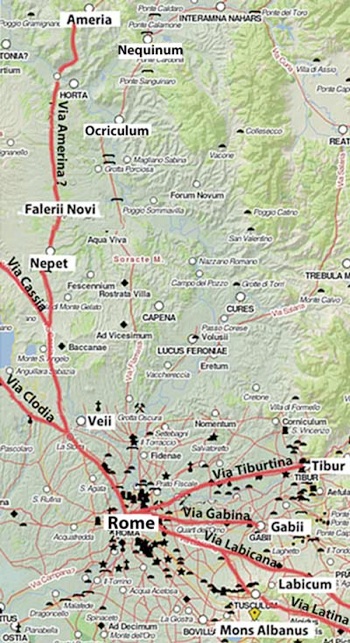

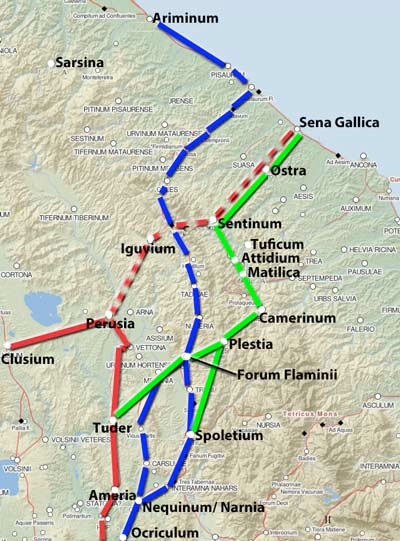

Dark blue = Via Flaminia; dotted dark blue = western branch);

Purple = Via Clodia; Green = Via Cassia; brown = Via Ciminia; grey = Via Traiana Nova

Red = Via Amerina (?);

For Giovanni Uggeri (referenced below), red = Via Annia; dotted red = Via Amerina

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Epigraphic Evidence

The only certain reference to Via Amerina in our surviving sources is in an inscription (CIL IX 5833, ca. 130 AD) from Auximum (modern Osimo in the Marches): it commemorates the splendidly named Oppius Sabinus Iulius Nepos Manius Vibius Sollemnis Severus, a patron of the colony, whose career had included the post of curatori viarum Clodiae, Anniae, Cassiae, Ciminae, trium Traianarum et Amerinae (curator responsible for the upkeep of a number of roads, including one called Via Amerina).

Martin Frederiksen and John Ward Perkins (referenced below, at pp 191-2) usefully put this inscription in context, starting with the observation that:

-

“From the time of Augustus, the maintenance of the great arterial roads of Italy lay in the hands of the curatores viarum, a board composed of men of consular or praetorian rank. Unlike the larger trunk roads such as the Via Flaminia or the Via Aurelia, which were each administered by a single curator, the Via Clodia and the Via Cassia were combined under one authority. By the 2nd century AD, this [authority was also responsible for] other roads [that were] sufficiently important to be kept up at public expense. ”

They then reproduced 15 inscriptions that recorded the title of this curator, of which twelve could be dated to the reign of a particular emperor (indicated in brackets in the list below, which also indicates the roads mentioned in the curator’s title):

-

CIL V 0877 (Trajan) Cassia; Clodia; Ciminia; Nova Traiana

-

CIL X 6006 (Hadrian) Clodia; Cassia; Ciminia

-

CIL IX 5833 (Hadrian) Clodia; Annia; Cassia; Ciminia; tres Traianae; Amerina

-

CIL III 1458 (Hadrian) Clodia; Annia; Cassia; Ciminia

-

CIL III 6813 (Hadrian) Clodia; Cassia; Annia; Ciminia; Traiana Nova

-

CIL III 7394 (Antoninus Pius) Clodia; Cassia; Annia; Ciminia; Traiana Nova

-

CIL VI 1356 (Marcus Aurelius) Clodia; Annia; Cassia; Ciminia; Nova Traiana

-

CIL XIV 2164 (Marcus Aurelius) Clodia

-

CIL II 1532 (Severus ) (Cassia; Ciminia;) Annia; Amerina; Clodia; tres Traianae

-

CIL VIII 2392 (Alexander Severus) Clodia

-

CIL VIII 7049 (Alexander Severus) Clodia; Cassia; Ciminia

-

CIL XI 6338 (Gordian III) Clodia

I have used italics in relation to CIL II 1532 because, as Giovanni Uggeri (referenced below, at p. 136, note 27) pointed out, the completion above is derived from old and erroneous transcriptions: the Heidelberg Database gives the transcription as ‘curatore anno ET AME(?)R CLODIANO [---] TEPPPRIA PRIMAM’.

The curator of CIL VIII 2392 and 7049 was the same person: P. Iulius Iunianus Martialianus, making it clear that the title of this curatorship could be variously abbreviated. As Frederiksen and Ward Perkins pointed out, the fullest form appears only in CIL IX 5833. From this, we learn that holder of this office was responsible for Via Clodia (which appears in every inscription) and seven other roads: Via Cassia; Via Annia; Via Ciminia; Via Amerina; and three roads named for the Emperor Trajan, one of which was Via Traiana Nova (see the map above). As Giovanni Uggeri (referenced below, at p. 137) observed, they seem to have:

-

“... constituted a group of roads north of Rome that gravitated around the Via Cassia, bounded by the western [coastal] system of the Via Aurelia and the eastern system of the Via Flaminia ...” (my translation).

As discussed below, it is usually assumed that Via Amerina, which appears in CIL IX 5833 and possibly in CIL II 1532, originally ran from Rome to Ameria (modern Amelia).

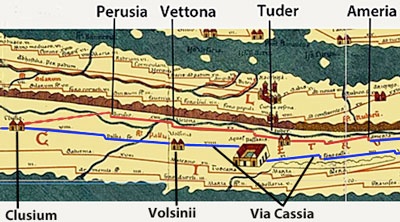

Tabula Peutingeriana

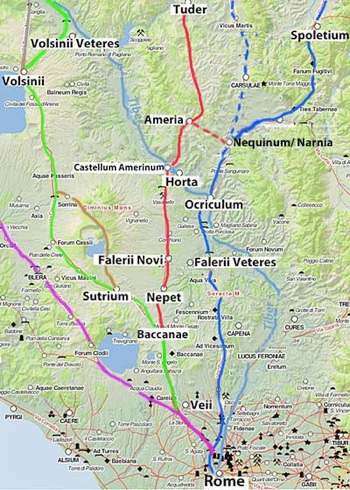

Tabula Peutingeriana (from the website by the Biblioteca Augustana der Fachhochschule, Augsburg)

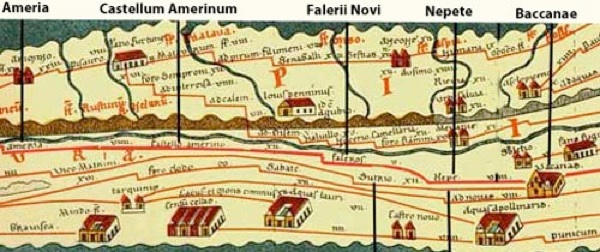

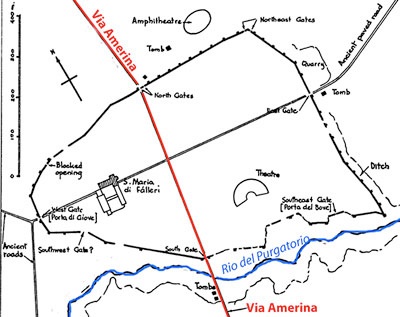

Road from Rome to Ameria (Via Amerina ?)

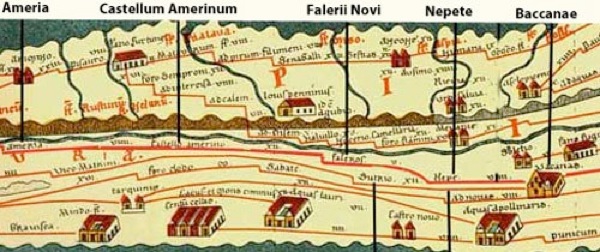

Detail of the above: Road from Baccanea to Ameria (Via Amerina ?)

An unidentified road on the so-called Tabula Peutingeriana (a medieval copy of an illustrated itinerary that probably dated to ca. 250 AD) branches off the via Cassia at ‘Vacanas’ (Baccanae) and continues to Ameria via:

-

✴‘Nepe’ (Nepet);

-

✴‘Faleros’ (Falerii Novi); and

-

✴‘Castello Amerino’ (a port on the Tiber that was discovered at Seripola, near Orte, in 1962-3).

According to the mileages on the Tabula, Ameria was 56 Roman miles from Rome by this route. Cicero probably referred to it in the speech in ca. 80 BC in which he defended Sextus Roscius of Ameria: he observed that news of the crime that his client was alleged to have committed in Rome:

-

“... arrives at Ameria by the first dawn of day. In 10 hours of the night, [the messenger bringing it from Rome] travelled 56 [Roman] miles in a gig”, (‘pro Roscio’, 19).

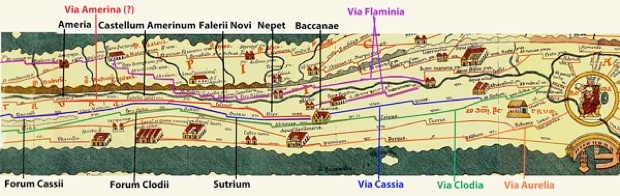

Tabula Peutingeriana (from the website by the Biblioteca Augustana der Fachhochschule, Augsburg)

Extension of possible Via Amerina from Ameria to Clusium

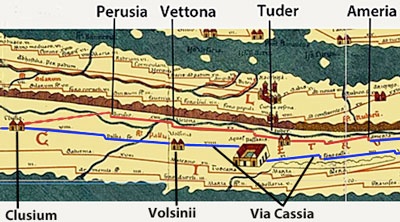

At the time of the Tabula Peutingeriana, this road continued from Ameria to:

-

✴Tuder (Todi);

-

✴Vettona (Bettona); and

-

✴Perusia (Perugia); with an extension to

-

✴Clusium (Chiusi), on Via Cassia.

Most scholars identify the whole of this road in the Tabula Peutingeriana as the Via Ameria that was recorded in ca. 130 BC in CIL IX 5833 (above). However, Giovanni Uggeri (referenced below) has recently called this identification into question.

Giovanni Uggeri: Via Annia and Via Amerina

Giovanni Uggeri (referenced below) suggested that the road from Rome to Ameria in the Tabula Peutingeriana was a portion of a long-distance consular road, the Via Annia, which began at Aquileia and which dated to 153 BC. It followed that this was also the Via Annia of CIL IX 5833, in which case, the Via Amerina of this inscription must have been another, presumably more minor road that ended at Ameria. As discussed below, he accepted that the original Via Amerina had been built in the 4th century BC, and that it ran from Rome to Ameria. However, he suggested (at p. 145) that, after the construction of Via Flaminia in 220 BC, this original road became relatively unimportant:

-

“In the period between the construction of Via Flaminia and that of Via Annia (i.e., 220-153 BC), ‘Via Amerina’ probably indicated the road that left Via Flaminia after it crossed the Nera at Narnia and ran west for about 6 [Roman] miles along the ridge up to Ameria. ... By this route, the distance from Rome to Ameria was at least 60 [Roman] miles, while after 153 BC, the Via Annia provided a direct route of 56 [Roman] miles.” (my translation).

On this model, the earlier road from Narnia to Ameria inherited the name Via Amerina’, and this this was the road that was under the care of the 'curator viarum Clodiae Anniae Cassiae Ciminiae trium Traianarum et Amerinae’ of CIL IX 5833 in ca. 130 AD, . (Uggeri’s Via Amerina is indicated as a dotted red line in the map at the top of the page).

I discuss the elements of this hypothesis below.

Via Annia

Peter Wiseman (referenced below) began his paper of 1964 by asserting that:

-

“Two viae Anniae are known: [one] in Etruria: and [the other] near Aquileia; and [a third] has been conjectured between Capua and Rhegium.”

The first two of these roads are relevant to the present discussion:

-

✴Scholars generally agree that the second of them ran from Aquileia to Patavium (modern Padua) and south, at least to Hadria (modern Adria).

-

✴Wiseman’s ‘Etruscan Annia’ (which was actually in Faliscan rather than Etruscan territory) was evidenced by two inscriptions from Falerii Novi (discussed below). He expressed what is probably the consensus view, that this:

-

“... was a minor road and is of only peripheral importance ...”

However, as we shall see, Giovanni Uggeri believed that both of these ‘viae Anniae’ belonged to the same long-distance road of this name.

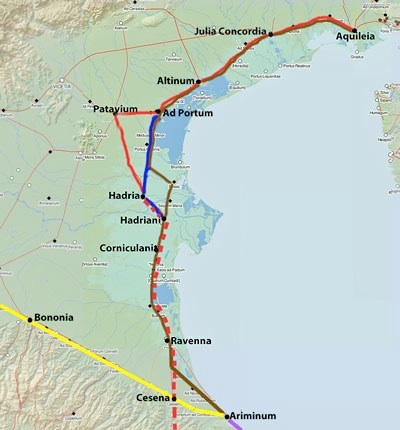

Red = generally accepted route of Via Annia from Aquileia to Hadria

Dotted red = Giovanni Uggeri’s proposed continuation of Via Annia (which continues to Rome)

Corniculani = find spot of the milestone discussed below

Blue = generally accepted route of Via Popilia from Ad Portum to Hadriani

Yellow = eastern end of Via Aemilia, to Ariminum

Purple = start of Via Flaminia at Ariminum

Brown = route from Aquileia to Ariminum in the Tabula Peutingeriana

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

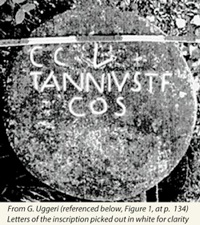

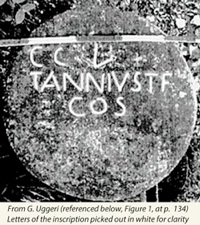

CCL (milia passuum)/ T(itus) Annius T(iti) f(ilius)/ co(n)s(ul)

(In this photograph, which is from Giovanni Uggeri’s paper, I have picked out the letters of the inscription in white for the sake of clarity.) Uggeri reasonably suggested that this milestone stood on the Via Annia that was already evidenced at Aquileia and Patavium.

Uggeri deduced (at pp. 137-8) the Titus Annius who had built this road was probably Titus Annius Luscus, the consul of 153 BC. Mario Adamo, for example, supported this element of Uggeri’s hypothesis, asserting that:

-

“... it is now clear, the via Annia was built by T. Annius Luscus, [the consul of] 153 BC.”

He cited Peter Wiseman (referenced below: 1964, at pp. 22–30; and 1969: at pp. 82–8), who had already come to this conclusion on the basis of other evidence (albeit that his suggested route had not passed through Corniculani: as he summarised (at p. 86 of the paper of 1969):

-

“It still seems to me probable that T. Annius Luscus, cos. 153 BC and patron of the colony [of Aquileia], built the Via Annia from Bononia to Aquileia, through Padua and Altinum.”

Uggeri pointed out (at p. 138) that:

-

“... to the right of the first two preserved letters [‘CC’ in the first line of the inscription], there is ... a long and accurate intentional erasure of some letters, which testifies to an ancient revision ... that led to the correction of the number of miles [to ‘CCL’], which is therefore accurate. ... The previous mileage consisted of several letters and was clearly shorter (eg CCXXXXV), because otherwise the [original] letter ‘L’ would have been left in place: instead [a new ‘L’] was engraved, widely spaced, above the erased area_ (my translation).

In short, in his view, the milestone had originally recorded a smaller number than 250 (perhaps 245), but this had been subsequently revised to what he presumed was a more accurate figure.

Since Aquileia was only 141 Roman miles from Corniculani, it was probably the end point of a road that started 250 Roman miles south of Corniculani. Uggeri observed (at p. 138) that:

-

“Given so high a figure, it seems to me that there can be no doubt that [this] starting point ... was Rome. The same starting point is found, for example, on two milestones from Bologna on the Via Aemilia, on which we read the numbers 268 and 286: [these mileages are] obviously counting from Rome and include ... the entire length of Via Flaminia[from Rome to Ariminum] and the portion of Via Aemilia from Ariminum to the respective milestones” (my translation).

In other words, the milestone found at Corniculani suggested that Titus Annius had built a consular road that ran from Rome, via Corniculani, to Aquileia.

Corniculani lies on a road depicted on the Tabula Peutingeriana that ran from Aquileia to Ariminum, at the start of Via Flaminia (marked in brown in the map above). It is thus possible that this was the Via Annia, and that travellers heading for Rome completed their journey on Via Flaminia. However, Uggeri estimated (at p. 139) that:

-

✴based on the two milestones at Bononia discussed above, the length of Via Flaminia was at least 207 Roman miles (a figure that is confirmed by the Antonine Itinerary for the route using the western branch of the road, via Mevania);

-

✴the minimum distance between Ariminum and Ravenna given in the surviving itineraries was 33 Roman miles; and

-

✴the distance from Ravenna to the find spot of the milestone at Corniculani was at least 30 Roman miles.

Thus, if the Via Annia had terminated at Ariminum, the milestone at Corniculani would have marked 270 or more, rather than 250, Roman miles. Uggeri therefore suggested (at p. 140) that a more direct route was required, which we might identify by connecting:

-

“... the various Viae Anniae that are documented at disparate points north of Rome, from the ager Faliscua to Aquileia, which have previously been considered separately. In other words, if we put together [all of] the testimonies ... , we can postulate a consular road that, in 153 BC, followed the shortest route from Rome to Aquileia” (my translation).

-

✴250 Roman miles from Rome to Corniculani; and

-

✴141 Roman miles from Corniculani to Aquileia;

giving an overall length of 391 Roman miles. This was consistent with the mileage recorded on the milestone.

However, there are potential difficulties with this proposed route, as discussed below.

Route from Ravenna to Vettona

Tabula Peutingeriana (from the website by the Biblioteca Augustana der Fachhochschule, Augsburg)

Purple = continuous road from Aquileia to Ariminum; Blue = Via Flaminia from Ariminum to Forum Flaminii

Red = part of a continuous road from Rome ( via Ameria and Perusia) to Clusium; Green - Via Cassia

Blue = route of Via Annia from Ravenna to Ameria proposed by Giovanni Uggeri

Yellow = Via Aemilia; Red = Via Flaminia; Green = Via Cassia

Brown = relevant parts of two separate routes in the Tabula Peutingeriana (above)

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Giovanni Uggeri acknowledged (at p147) that there is no evidence for the route from Vettona to Ravenna: he observed that, at Collestrada, just north of Vettona, the putative Via Annia:

-

“... crossed the Roman road that ran [east-west] from Asisium to Perusia, which was part of a road that connected Via Flaminia and Via Cassia. The [Tabula Peutingeriana] recorded [part of this road, from Vettona] ... to Perusia and Clusium [marked in brown on the map above. There is no record in the Tabula of] the continuation northwards of the Via Annia, which is what interests us here: it was clearly not very important in the imperial age. In fact, in late antiquity, roads were favoured at lower altitudes and for more densely inhabited places: in particular, via Flaminia was usually the preferred route to Cisalpina “(my translation).

My View

This undocumented stretch of the putative consular road through Tifernum Tiberinum (modern Città di Castello) runs for some 130 Roman miles, and thus constitutes about a third of the total. Uggeri suggests that it was not included in any of the surviving itineraries because it it was not particularly important by the time that they were compiled. However, there is also no surviving evidence that it was of any particular importance even in the Republican period. For example, Via Aemilia (marked in yellow on the map above), which was built in 187 BC, continued past Cesena to Ariminum, from whence travellers continued to Rome along Via Flaminia. It seems to me that, if it were not for the ‘CCL’ of the inscription from Corniculani, one would reasonably assume that Via Annia followed the entire route of the Tabula Peutingeriana, terminating (like Via Aemilia) at Ariminum.

Via Annia at Falerii Novi

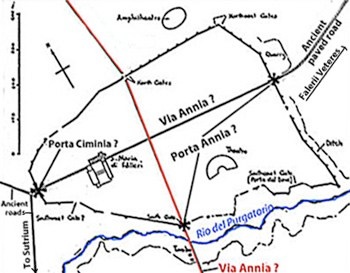

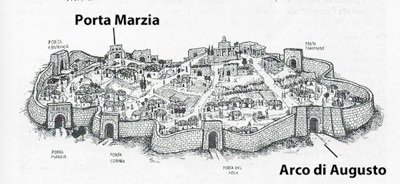

Falerii Novi (adapted from Frederiksen and Ward Perkins, referenced below, Figure 26, at p. 156)

Falerii Novi was founded in or soon after 241 BC on a site between Ameria to the north Nepet and Rome to the south. Ugggeri asserted (at p. 143) that its:

-

“... main street, which ran from north to south, was used by the via Annia, a road recorded in relation to a via Augusta by two inscriptions [from the city]” (my translation).

The two inscriptions in question are:

-

✴CIL XI 3083, a fragment of which was reused in the episcopal palace of Cività Castellana (Falerii Veteres): this inscription, which can be dated to the period 2 BC - 14 AD, recorded that four magistri Augustales paved a stretch of Via Augusta:

-

• ab Via Annia extra portam ad Cereris

-

(from Via Annia, outside the gate, to the Temple of Ceres).

-

✴CIL XI 3126, which no longer survives but which is thought to have come from Falerii Novi and to date to the 2nd century AD: this inscription recorded that a father and son financed the restoration of

-

•a stretch of Via Augusta:

-

-a porta Cimina usque ad Anniam

-

(from Porta Cimina to either Via Annia or, possibly, Porta Annia); and

-

•a stretch of the via sacra:

-

-a chalcidico ad lucum Iunonis Curritis

-

(from the Chalcidicum to the grove of Juno Curitis [at Celle, below Falerii Veteres]).

Martin Frederiksen and John Ward Perkins (referenced below, at pp. 190-1) set out to disprove the hypothesis (first suggested in 1864) that the Via Annia recorded in these inscriptions ran north-south across the city: to this end, they analysed the topographical information that might be gleaned from these inscriptions:

-

✴They asserted (at p. 191) that:

-

“... it is quite clear from [CIL XI 3083] that Via Augusta lay, as one would expect, outside the city.”

-

In other words, the four magistri Augustales paved an extramural stretch of Via Augusta that started at Via Annia, outside one of the city gates, and continued to what they assumed to be an extra-mural Temple of Ceres. (On Uggeri’s hypothesis, the city gate in question would have been either the north or the south gate).

-

✴They reasonably assumed (at p. 190) that the ‘Porta Cimina’ of CIL XI 3126 faced the Ciminian forest or mountain and was therefore, almost certainly, the main west gate of the city. Thus, if Via Annia was the north-south street, the father and son of CIL XI 3126 must have paved a stretch of Via Augusta that ran along:

-

“ ... the [intramural] axial street ... leading eastwards from [the west gate] towards the centre ...”

They asserted that, if Via Annia ran north-sout, then the implications for Via Augusta from the two inscriptions were mutually exclusive: thus Via Annia must have been another road in the vicinity. They tentatively suggested (at p. 191) that it was the ancient road from the western gate that ran southwest towards Sutrium. This road crossed:

-

“... the ridgeway road south of the Rio del Purgatorio, [which,] although seemingly unpaved, was an ancient cross-country road of considerable local importance, linking Sutrium with Falera Veteres and later with Falerii Novi. In Roman, as in Faliscan, times, it must have been one of the principal roads within the territory. Can this be the Via Annia ?”

They concluded (still at p. 191) that:

-

“Whether or not these are the correct identifications of Via Annia and Via Augusta (and it must be stressed that the evidence is far from conclusive), it is clear that Via Annia cannot possibly be the [main north-south road at] Falerii Novi.”

Peter Wiseman (referenced below, at p. 22, note 7) cited this passage from Frederiksen and Ward Perkins when asserting that the Via Annia of these inscriptions was a minor road that ran west to east between Sutrium, Falerii Novi and Falerii Veteres.

However, as noted above, it is unclear whether the stretch of Via Augusta recorded in CIL XI 3126 extended from Porta Ciminia to:

-

✴Via Annia (as Frederiksen and Ward Perkins assumed); or

-

✴Porta Annia.

Thus, for example, the author of this entry in the ‘Enciclopedia dell' Arte Antica’ (1994) assumed that its destination was Porta Annia:

-

“Road maintenance works [at Falerii Nova] affected the Via Augusta in the extramural stretch ... between the western gate, known as Cimina, and the southern gate, known as Annia ...” (my translation).

If, in the light of this, we look again at the description of the stretch of Via Augusta recorded in CIL XI 3083:

“ab Via Annia extra portam ad Cereris”

It is possible that this gate was meant to be recognised as the Porta Annia. In other words, it is possible that both inscriptions indicate that Via Augusta ran outside the city walls, passing Porta Cimina and Porta Annia, the latter being the gate on Via Annia. We cannot assume that this was either the north or the south gate: it might, for example, have been the east gate,which would mean that Via Annia ran west-east through Falerii Novi and possibly continued towards Falerii Veteres as the sacra via. of CIL IX 3126.

My View

Given the ambiguous syntax of the inscriptions and the fact that the location of the Temple of Ceres in CIL IX 3083 is unknown, these inscriptions can probably neither prove or disprove the hypothesis that Via Annia ran north-south across Falerii Novi (as Giovanni Uggeri hypothesised) and thus formed part of a consular road from Rome to Aquileia.

Viae Annia and Amerina of CIL IX 5833

Purple = Via Clodia; Green = Via Cassia; brown = Via Ciminia (?); black = Via Traiana Nova

Yellow = Via Aurelia; Dark blue = Via Flaminia

For Giovanni Uggeri (referenced below), red = Via Annia;Via Amerina runs from Ameria to Narnia

Note that the putative stretch of Via Annia from Vettona to Ravenna is unattested in surviving itineraries

Corniculani and Falerii Novi = locations of inscriptions relating to Via Annia

Dotted red = road from Vettona to Perusia and Clusium on the Tabula Peutingeriana

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

As noted above, an inscription (CIL IX 5833, ca. 130 AD) comemorated an individual who had held the post of:

curatori viarum Clodiae, Anniae, Cassiae, Ciminae, trium Traianarum et Amerinae

As Giovanni Uggeri (referenced below, at p. 137) observed, the roads under the care of this curator, which included Via Annia and Via Amerina:

-

“... constituted a group of roads north of Rome that gravitated around the Via Cassia, bounded by the western [coastal] system of the Via Aurelia and the eastern system of the Via Flaminia ...[marked, respectively, in yellow and blue in the map above]” (my translation).

Again as noted above, variously abbreviated forms the title of this curator are found in eleven reasonably complete inscriptions from the imperial period (including CIL IX 5833):

-

✴Via Clodia appears in all eleven:

-

✴each of Via Cassia and Via Ciminia appears in eight;

-

✴each of Via Annia and Via Traiana Nova (either alone or as one of three roads named for Trajan) appears in five; and

-

✴Via Amerina appears only once, in CIL IX 5833.

Via Clodia and Via Cassia (marked, respectively, in purple and green) both started at Rome:

-

✴Via Clodia ran to Saturnia and then turned towards the coast to join the Via Aurelia; and

-

✴Via Cassia traversed Etruria to Florentia and Lucca.

Two of the others began and ended on Via Cassia:

-

✴According to Alessandra Milioni (referenced below, at p. 9, note 4), Via Ciminia probably branched off Via Cassia at Sutrium, passed along along the east side the Lago di Vico and continued towards modern Viterbo, rejoining the Via Cassia near the present-day Bagnaccio.

-

✴ According to William Harris (referenced below, 1965, see Figure 1 at p. 115), Via Traiana Nova left Via Cassia at Volsinii (modern Bolsena) and ran northwards to rejoin it about half way between Volsinii and Clusium (modern Chiusi), thereby significantly shortening the route between these two centres.

These short roads are indicated in brown and black respectively on the map above.

That leaves Via Annia and Via Amerina: on Uggeri’s hypothesis:

-

✴Via Annia was the consular road from Rome to Aquileia; and

-

✴Via Amerina was another, much less important road, possibly the one linking Ameria to Narnia, on Via Flaminia.

My View

I think that this is perhaps the most difficult aspect of Uggeri’s hypothesis:

-

✴If each of Via Flaminia and Via Aurelia had its own curator, why was this not the case for the putative Via Annia from Aquileia to Rome?

-

✴If the Via Annia cared for by the curator of CIL IX 5833 was the consular Via Annia, why (given its importance) did it appear in only five of the inscriptions recording his title?

I think that it is more reasonable to assume that:

-

✴the Via Annia of CIL IX 5833 was, as Fredericksen and Ward Perkkins suggested, another road that ran through or near Falerii Novi, perhaps the road from Sutrium to Falerii Veteres; and

-

✴Via Amerina was (as usually assumed) the road from Rome to Ameria and Perusia shown in the Tabula Peutingeriana.

Giovanni Uggeri: Viae Annia and Amerina: My Conclusions

Giovanni Uggeri is surely correct that the milestone found at Corniculani marked the distance from Rome along a consular road called Via Annia, which ended at Aquileia. However, I think that, for the reasons set out above, his hypothesis that it continued south via Falerii Novi to Rome is open to question. A more obvious route is suggested by the Tabula Peutingeriana, which would have the Via Annia from Aquileia terminate, (like Via Aemilia) at Ariminum.

However, I wonder whether this inscription can really take the weight that Uggeri places on it. He asserted (at p. 138) that the revision of the original mileage to read ‘CCL’ was done as a correction and was therefore likely to be accurate. However, Mario Adamo (referenced below, at section 2.4) asserted that:

-

“The Codigoro milestone now reveals that, when roads changed their itineraries, milestones also underwent modifications” (my italics).

My intention here is not to speculate on which of these two conjectures is the more likely: I simply suggest that the reason for the revision is unknown and that the revised figure cannot necessarily be considered to be any more accurate than the original. In any case, we can only rely on this mileage when determining the route of the road if it is beyond doubt that the milestone was found in the place where it stood at the time of this revision.

In summary, I think that, in the absence of

-

✴any new evidence to confirm that the Via Annia that is epigraphically attested at Falerii Novi ran north-south across the city; or

-

✴any other evidence for Via Annia south of Ravenna;

we must assume that it terminated at Ariminum.

M. Frederiksen & J. Ward Perkins: Via Amerina

Tabula Peutingeriana (from the website by the Biblioteca Augustana der Fachhochschule, Augsburg) Road from Baccanea to Ameria (Via Amerina ?)

As noted above, a road in the Tabula Peutingeriana from Baccanae to Ameria is usually identified as part of the Via Amerina of CIL IX 5833. Martin Frederiksen and John Ward Perkins (referenced below, hereafter F-WP) published a detailed description of part of this road, between Baccanae and the Tiber. They concluded (at p. 187) that:

-

“We can hardly doubt that it was laid out following the final conquest of the Faliscans [and the foundation of Falerii Novi] in 241 BC ...”

This has become the ‘conventional wisdom’, not only regarding this stretch of the road: one often reads that Via Amerina, in its entirety, dates to 241 BC. This section looks at the evidence as it relates to the ‘Romanisation’ of the stretch from Baccanae to Ameria.

Conquest of the Faliscans

Four fragmentary record this conquest:

-

✴Cassius Dio:

-

“... the Romans made war upon the Faliscans and [the consul] Manlius Torquatus ravaged their country. ... he was victorious and took possession of ... half of their territory. Later on, the original city, which was set upon a steep mountain, was torn down and another one was built, easy of access”, (‘Roman History’, 7: fragment 18).

-

✴Eutropius:

-

“[The consuls] Quintus Lutatius and Aulius Manlius ... made war upon the Falisci ... and [were victorious] within 6 days: 15,000 of the enemy were slain and peace was granted to the rest, but half their land was taken from them” , (‘Breviarium’’, 2: 28)..

-

✴Polybius:

-

“[Immediately after] the confirmation of the peace [with Carthage at the end of the First Punic War, the Romans engaged in] war against the Faliscans. They [captured] Falerii after only a few days' siege”, (‘Histories’, 1:65).

-

✴Livy:

-

“When the Faliscans revolted, they were subdued on the 6th day, and their surrender was accepted”, (‘Periochae’, 20).

The Romans clearly saw this as a significant victory: the “Fasti Triumphales” record that each of the consuls of 241 BC (Aulus Manlius Torquatus Atticus and Quintus Lutatius Cerco) was awarded a triumph “over the Falisci”. Eutropius and Cassius Dio agreed that the Romans had confiscated half the territory of Falerii at this time, but Cassius Dio is the only one of the surviving sources to record the destruction of Falerii (now known as Falerii Veteres) and the construction of a new city (now known as Falerii Novi). However, the archeological evidence is broadly consistent with his account.

Date of the Stretch of Via Amerina near Falerii Novi: View of F-WP

Falerii Novi (adapted from Frederiksen and Ward Perkins, referenced below, Figure 26, at p. 156)

F-WP (referenced below, at p. 187) based their dating of this stretch of road on the archeological evidence from Falerii Novi that was then available to them (summarised in the diagram above). They argued that:

-

“The fact that the north-south axis of [Falerii Novi] is carefully aligned upon the one place where the Rio del Purgatorio was readily bridgeable shows clearly that [the builders of new city] had such a road in mind from the outset. We may [therefore] date Via Amerina with some confidence to 240 BC or very soon thereafter.”

They pointed out (at p. 108) that:

-

“After entering the south gate of Falerii Novi, Via Amerina continued straight across the town, crossing the main east- west road [the decumanus maximus] at right angles, and leaving by the north gate. Here, for the first time [for many miles], it changed direction and swung slightly to the left ... [It seems likely that] the two considerable gorges [ahead], the Rio Fratta and the Fosso delle Chiare Fontane, ... induced the Roman road-makers to deviate slightly from their previous line.”

They discussed (at p. 190) the possibility that the road beyond the north gate belonged to a separate phase of construction. However, they concluded (at p. 191) that:

-

“There is no reason whatever ... to doubt that the stretch of the Via Amerina to the north of Falerii Novi is contemporary with [that] to the south. Its course is less rigidly planned because the country was more open, [which allowed the builders] to circumvent such major obstacles as the Rio Fratta ... ; but there are exactly the same abnormally wide cuttings and easy gradients in both stretches, and Falerii Novi was clearly laid out with such a northward road in mind. Town and road were part of a single scheme for the control and development of the newly subjected ager Faliscus.”

View of Simone Sisani and Filippo Coarelli

Urban plan revealed by the excavation of the northern part of Falerii Novi in 2002-8

Via Amerina is shown in red

Blue lines enclose the central orthogonal grid; green line indicate a putative processional route

From S. Hay et al., referenced below, Figure 2 (at p. 4)

These two authors, in separate papers (referenced below), argued that Via Amerina had significantly pre-dated the construction of Falerii Novi in ca. 240 BC and that the archeological evidence from Falerii Novi that has become available in recent years supports this hypothesis.

This recent evidence is summarised in the plan above, which appeared in one of a series of publications by the team responsible for the excavation. It reveals that Via Amerina does not cross the city in a straight line, as F-WP had assumed: it diverges to the east as it approaches the north gate and then diverges to the west at the gate, from which point it continues at 15° west of north for several miles. In a recent paper, Simon Keay and Martin Millett (referenced below, at p. 366, Figure 18.5) summarised the latest view of the excavators in relation to the chronology of the urban development of the site. Their interpretation was based on the implicit assumption that Via Amerina and the central orthogonal grid of streets at Falerii Novi were all laid out ca. 240 BC. On this basis, they suggested that this was followed by:

-

✴the establishment of what was a processional route (marked in green above);

-

✴the construction of the city walls; and (finally)

-

✴the urban development of the area between the central grid and the city walls.

However, Simone Sisani (at p. 120) suggested that the course of Via Amerina had imposed the irregularities that are evident in the street plan:

-

✴the northern insulae are trapezoidal rather than rectangular; and

-

✴the north gate (unlike all the other gates in the city walls) is not centrally placed between the towers that flank it.

He argued that these irregularities:

-

“... testify to the fact that [Via Amerina] predated the urban plan, which adapted to it. The chronology of the road and the city [assumed by the excavators] must therefore be overturned ... : the existence of the Via Amerina determined the choice of the site for the rebuilding of Falerii in the aftermath of the events of 241 BC” (my translation).

Filippo Coarelli (referenced below) agreed with this revised chronology. In particular, he argued (at p. 101) that the excavators’ assumption that the central orthogonal grid was contemporary with the Via Amerina and that it pre-dated the irregular development of the peripheral area of the city is unsustainable:

-

“As is easily understood, the existence of a regular urban nucleus is an element that strongly influences all successive amplifications. This is not just an argument from common sense: it is a historical fact, and the onus is on those who wish to argue to the contrary to prove their case” (my translation).

In his view (if I have understood it correctly), the pre-existing line of Via Amerina conditioned the originally irregular urban plan, upon which the central orthogonal element was subsequently superimposed.

My View

The view that Via Amerina was established in 241 BC has become become widely accepted (despite the dissenting voices discussed above). It is largely based on the view ofF-WP, who argued that:

-

✴“The fact that the north-south axis of [Falerii Novi] is carefully aligned upon the one place where the [nearby] Rio del Purgatorio was readily bridgeable shows clearly that [the builders of new city] had such a road in mind from the outset. We may [therefore] date the Via Amerina with some confidence to 240 BC or very soon thereafter.”

-

✴Falerii Novi was clearly laid out with [the northward course of Via Amerina] in mind. Town and road were part of a single scheme for the control and development of the newly subjected ager Faliscus.”

I find these arguments unconvincing: surely:

-

✴Via Amerina would have been ‘carefully aligned upon the one place where the Rio del Purgatorio was readily bridgeable’ whenever it was built; and

-

✴the urban plan of Falerii Novi might well have respected its northward course because it already existed.

I think it more likely that, as argued by Simone Sisani and Filippo Coarelli, the presence of Via Amerina was one of the factors that determined the location of Falerii Novi. (I think that the factor that determined its position on this road was the intention to construct a processional route from Falerii Novi to the sanctuaries of Falerii Veteres such as the grove dedicated to Juno Curitis mentioned above.)

Date of the Road from Baccanae to the Tiber: View of F-WP

F-WP (referenced below, at p. 187) observed that:

-

“Constructionally, [Via Amerina] is... a road of marked contrasts. There were [some] stretches, notably on either side of Falerii Novi, where it was patently laid out ex novo by the Roman engineers; [and] others (as, for example, Corchiano, [some 10 km north of Falerii Novi]) where it was almost certainly following the line of a pre-existing Faliscan road.”

They also observed (at pp. 187-8) that the stretch south of Nepet:

-

“... has all the characteristics of an earlier road [that was subsequently] paved in the Roman manner ... , taken into use with seemingly little change. This earlier road can hardly be other than [the one that had] served the colony at Nepete [founded by the Latins and Romans in ca. 383 BC] for over a century: and this, in turn, may well have followed the line of a yet earlier Etruscan road between Veii and the pre-Roman Nepete.”

In other words, Frederiksen and Ward Perkins concluded that the entire road from Baccanae in the south to the northern boundary of the ager Faliscus was part of a single project of ca. 240 BC, albeit that it had included both:

-

✴the construction ex novo of some stretches (like those on either side of Falerii Novi); and

-

✴the incorporation and repaving of other stretches of earlier Etruscan and Faliscan roads.

These authors did not comment on the dating of the road north of the Tiber.

View of Simone Sisani and Filippo Coarelli

As discussed below, both of these authors believed that the Via Amerina between Rome and Ameria was incrementally ‘Romanised’ along its length in line with the conquest of the territory that it crossed. The land south of the Tiber was all under Roman hegemony by the middle of the 4th century BC, and the Romanisation of the road probably extended to Ameria soon after.

My View

I agree with Sisani and Coarelli that a Roman (or Romanised) road along the route of the future Via Amerina probably reached the Tiber soon after the conquest of the Faliscans in 351 BC and probably extended as far as Ameria by or soon after the end of the century. The destruction of Falerii Veteres in 241 BC after decades of peace was almost certainly an unforeseen and shocking postscript to these events. The subsequent foundation of Falerii Novi might well have prompted the restoration of this stretch of road, but I can see no basis for the ‘conventional wisdom’ that the foundation of this city gave rise to the construction or Romanisation of the road.

Simone Sisani and Filippo Coarelli

Date of the Road from Rome to Ameria

Simone Sisani (referenced below, at p. 117) noted that the existence of the curator viae Ameriniae of CIL IX 5833 indicated that this was a public road and that it was therefore:

-

“... certainly opened, like the other viae publicae, on the direct initiative of the Roman state”, (my translation).

He observed (at p. 118) that:

-

“The name ‘Via Amerina’ is odd, given the fact that, strictly speaking, it reached Perusia: this seems to indicate a long road that, in an initial phase, must evidently have terminated at Ameria” (my translation).

Furthermore, since Via Amerina:

-

“... was not named for the consul or censor who had originated it, it must have pre-dated 312 BC, when the opening of the Via Appia [which was named for the censor Appius Claudius Caecus] inaugurated a new [naming convention for public roads] that was never [subsequently] abandoned”, (my translation from p. 118).

He suggested (as noted above) that the stretch of the road in the ager Faliscus would have follwed the conquest of the Faliscans in 351 BC, which led to a truce for 40 years and a request from Falerii (later Falerii Veteres) in 343 BC that this should be replaced by a foedus (treaty). He further suggested (at p. 120) that it extended into Umbria in the late 4th century BC and was probably the first public road that the Romans opened on Umbrian soil.

Archaic roads to Tibur, Gabii and Labicum and southern stretch of Via Amerina/ Cassia

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Filippo Coarelli (referenced below), in an article that cited the earlier work of Simone Sisani, largely agreed with his conclusions. However, he made an important observation (at pp. 102-3) relating to the status of the original Via Amerina and that of its later extension:

-

“While, originally, the destination of this road could only have been Ameria, [its subsequent extension to Perusia and beyond, discussed below] ... can probably be identified with the creation of the via publica [named in CIL IX 5833]...” (my translation).

He continued:

-

“In the case of the original Via Amerina, ... we are [probably] dealing with a typical example of the archaic roads that connected Rome with nearby cities from which they took their names (Labicana, Tiburtina, Gabina etc.)”, (my translation).

He suggested that only the part of these roads nearest to Rome would originally have been under Roman control: the other part, in each case, would have been under the control of the centre for which it was named. He therefore suggested that Rome’s responsibility for Via Amerina would have extended northwards in line with the phasing of the Roman conquest and observed (at p. 103) that it:

-

“... can have entered under Roman control [throughout its length] only ... after the foedus of 308 BC with [the Umbrian city of] Ocriculum”, (my translation).

Coarelli developed this argument (at p. 102):

-

“... the name ‘Via Amerina’ is explicable only if we are dealing with a road built before 312 BC, after which ... Roman roads were given the names of their founders: those designated by the names of their destinations are, without exception, archaic roads. Naturally, it is possible (indeed probable) that we are dealing with an ancient road that was integrated into the Roman road system only in a later phase, after the Roman conquest. This was probably in relation to an extension of the road to the north [towards Perusia]:

-

✴[One example of such a two-phase process involves] the Via Tiburtina Valeria, except that, in our case, [Via Amerina] preserved its original name [while Via Tiburtina subsequently assumed what was probably the name of the magistrate responsible for its extension towards the northeast].

-

✴[Another important example involves] the Via Latina, which was originally named for Monte Albano, the seat of the Latin League, but which preserved this name after it had been extended as far as Capua.

-

This model seems to be confirmed [in the case of Via Amerina] by the fact that, while its original destination cannot have been other that Ameria, it was subsequently extended to Perusia ... as indicated by later itineraries. This extension, which might be associated with the creation of the via publicae, seems to date to the 3rd century BC [see below]. It follows that the stretch between Rome and Ameria is certainly earlier, and thus not later than the 4th century BC” (my translation).

In other words, Sisani’s hypothesis, as modified by Coarelli, assumes that:

-

✴Via Amerina was built in the 4th century BC and the Romans controlled it over its entire length by the end of the century; and

-

✴it was subsequently extended to Perusia and beyond, but retained its original name.

Date of the Road from Rome to Ameria: View of Giovanni Uggeri

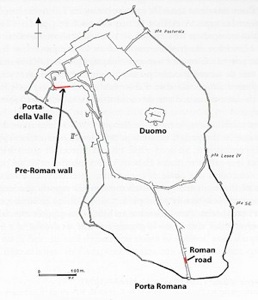

Pre-Roman wall Ancient Ameria Roman road

From P. Fontaine (referenced below, Figure 5 at p. 76)

As noted above, Giovanni Uggeri did not deny the existence of a road from Rome to Ameria prior to the putative construction of Via Annia. He asserted (at p. 145) that:

-

“The urban plan of the ancient city of Ameria, surrounded by mighty walls, was rearranged by the Romans [after the conquest]. A pre-Roman Via Amerina already arrived here: it entered the Porta Romana and climbed up to the top of the city ... The name taken from the destination city indicates that this road dated back to the 4th century BC. [For this hypothesis, Uggeri (at note 92) cited Simone Sisani, as above] In this case we should think of the road that originally connected Veii with the agro Faliscus and then with Horta and Ameria” (my translation).

This description is slightly compressed. It is certainly true that the stretch walls that survives near Porta della Valle (seen on the right in the photograph above on the left) seems to date to the 5th or 4th century BC. However, this was a relatively short circuit of walls that probably protected an acropolis the highest point in the city (now occupied by the Duomo). Paul Fontaine (referenced below, at p. 79) suggested that the surviving stretches of the outer city walls that flank the medieval Porta Romana (the point at which a brnach of Via Amerina would have entered the city) date to the 3rd century BC, if not later. We have no evidence for city walls at Ameria before that date, although a stretch of a Roman road (see the photograph above on the right) under what is now Via della Repubblica (inside Porta Romana) could indicate the line of Uggeri’s ‘pre-Roman Via Amerina’.

Date of the Road from Rome to Ameria: My View

Since we know nothing of a Roman public road called Via Amerina before ca. 130 AD, we can only turn to the historical context in order to illuminate its likely history. It seems to me that its precursors of Via Amerina and Via Cassia must have reached Nepet and Sutrium respectively soon after ca. 383 BC, when colonies of the Latin League were founded at each of these locations: as Livy observed:

-

“... these places, fronting Etruria, served as gates and barriers on that side [of Roman territory] ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 9: 3-4).

These strategic centres provided the bases from which the Romans advanced northwards into Etruria and Umbria in the following period:

-

✴We can observe this growing presence most dramatically along the future line of Via Flaminia (built by the censor Caius Flaminius in 220 BC):

-

•Livy recorded that, in 308 BC, after the Romans defeated ‘the Umbrians’ near Mevania:

-

“The Ocriculans were admitted to a treaty of friendship with a ‘sponsio’ [a promise given by a commander in the field, which required subsequent ratification by the Senate]” (‘Roman History’, 9:41).

-

Scholars generally assume that this sponsio was subsequently transformed into a foedus (formal bilateral treaty of alliance).

-

•In 299 BC, the Romans took Umbrian Nequinum (only about 13 km from Ameria) and founded the Latin colony of Narnia on the site.

-

•In 241 BC, they founded another Latin colony on the site of Umbrian Spoletium.

-

✴The road through Sutrium (either the Via Cassia or its precursor) was presumably extended northwards towards Volsinii (on the shore of what is now Lake Bolsena) in 264 BC, after the people of Volsinii Veteres were moved here.

-

✴The precursor of Via Amerina presumably extended northwards from Nepet across the ager Faliscus, quite possibly as far as the Tiber, following the foedus requested by and presumably granted to Falerii Veteres in 343 BC.

On this model, the Roman public road known as Via Amerina would have come into being at some time after 343 BC, at a time when Ameria was fully within the orbit of Rome.

In order to proceed further with this line of thought, we need to consider what is known about the history of Ameria., a city taht is not named in our surviving sources until the late Republic (see below). However, as noted above, a nucleated Umbrian community seems to have developed on the present site of Amelia in the 5th or 4th century BC, with its fortified acropolis the highest point in the city. It enters recorded history in ca. 80 BC, when (as noted above) Cicero defended one of its citizens, Sextus Roscius. This unfortunate man was accused of having murdered his eponymous father, who

-

“... was a citizen of Ameria, by far the first man not only of his municipality, but also of his neighbourhood, in birth, and nobility and wealth, and also of great influence, from the affection and the ties of hospitality by which he was connected with the most noble men of Rome (‘pro Roscio’, 15).

Thus we learn that, by this time, Ameria was a thriving municipium. Moreover, as William Harris (referenced below, 1971, at p. 100) observed, if Cicero:

-

“... was using the word ‘hospitium’ (as he regularly did) in its strict sense, to refer to a relationship between a Roman and a peregrinus, [then this would suggest that] Ameria had a foedus with Rome [until the Social War] ...”

We might push this further and suggest that this putative foedus was in place by 299 BC, when nearby Nequinum was foolish enough to resist the Romans and suffered accordingly. In other words, it seems to me that the earliest stretch of the Via Amerina of CIL IX 5833, from Rome to Ameria, was probably entirely Romanised by ca. 300 BC.

Date of the Road from Ameria to Perusia

Tabula Peutingeriana (from the website by the Biblioteca Augustana der Fachhochschule, Augsburg)

Extension of possible Via Amerina from Ameria to Clusium

As note above, by the time of the Tabula Peutingeriana (probably ca. 250 AD), it seems that the ancient Via Ameria (discussed above) continued to:

-

✴Tuder (Todi);

-

✴Vettona (Bettona); and

-

✴Perusia (Perugia); with an extension to

-

✴Clusium (Chiusi) on Via Cassia.

Both Simone Sisani and Filippo Coarelli argued that this road reached Perusia in the 3rd century BC.

Walls and Gates of Perusia

From Enzo Amorini (referenced below, at p. 15)

Simone Sisani asserted (at p. 121) that:

-

“The extension [of Via Amerina from Ameria to] Perusia... must ... have been completed within the early decades of the 3rd century BC: the terminus ante quem is represented by the reconstruction of the Etruscan walls of Perusia, which took place no later than the middle of the century: its southern gate, Porta Marzia, which monumentalised the entrance to the city, clearly presupposed [the] existence [of this extension]” (my translation).

Filippo Coarelli addressed this point in more detail (at p. 121), citing the work of Francesco Roncalli (referenced below). He observed that the walls of Perusia had been built:

-

“... in two phases, to be dated to the 4th and 3rd centuries BC: the two monumental gates, Porta Marzia and the Arco di Augusto, certainly belong to the second phase: they are very close, both structurally and stylistically, to the Porta Giove at Falerii Novi [i.e. the western gate, which is named for the relief on its keystone], which can be dated to soon after 241 BC. These two gates [at Perusia] constitute precisely [and respectively]:

-

✴the point at which Via Amerina entered the city from the south; and

-

✴the point at which it exited from the north, immediately splitting into two branches:

-

•one directed westwards to Clusium [where in rejoined Via Cassia]; and

-

•the other eastwards to Iguvium [modern Gubbio]” (my translation).

Simone Sisani suggested (at p. 121) that the extension of Via Amerina to Perusia might have been associated with:

-

“... the conquest of the ager Gallicus by Manius Curius Dentatus in 284 BC. In fact, before the construction of Via Flaminia [in 220 BC], the link between Rome and the Adriatic area could have been ensured by the Via Amerina: [the putative extension] to Iguvium and the Scheggia pass [across the Apennines] constituted a route that (significantly) seems to be oriented towards Sena Gallica, the first colony of the Adriatic [which was founded immediately after the conquest]. ... This allows the hypothesis that [the extension of] Via Amerina might be attributed to Curius Dentatus ...” (my translation).

However, Filippo Coarelli suggested (at p. 103) that the extension more probably post-dated the conquest of Sarsina in 266 BC, at which point:

-

“... the conquest of Umbria seems to have been completed. This could suggest a link to the foundation of the colony at Ariminum [on the Adriatic coast north of Sena Gallica] in 267 BC: it seems [unlikely that], before the construction of Via Flaminia, there was no link between [Rome] and the new colony ... The only reasonable solution is that the extension of Via Amerina to Iguvium constituted precisely this necessary link [between Rome and] the ager Gallicus and Ariminum” (my translation).

Date of the Road from Ameria to Perusia: My View

Perusia: Porta Marzia Falerii Novi: Porta Giove Perusia: Arco di Augusto

Although, as Filippo Coarelli observed, the Porta Marzia and Arco di Augusto at Perusia were probably monumentalised in the second phase of construction of the city walls, there were almost certainly gates at these points in the original pre-Roman circuit. This suggests that Perusia was already linked to Tuder and Ameria to the south, to Clusium to the northwest and to Iguvium to northeast in pre-Roman time. It is certainly possible that, as Filippo Coarelli asserted, Porta Marzia (the surviving elements of which are now embedded in the wall Rocca Paolina) and Arco di Augusta were monumentalised in ca. 240 BC, at about the time of construction of Porta Giove at Falerii Novi: if so this might have coincided with the Romanisation of Via Amerina as far as Perusia. However, the fact remains that the earliest hard evidence that Via Amerina was extended to Perusia is from the Tabula Peutingeriana (ca. 250 AD).

Red = Probable Via Amerina from the Tabula Peutingeriana

Dotted red = extension via Iguvium to the Adriatic proposed by Simone Sisani and Filippo Coarelli

Blue = Via Flaminia (220 BC); Green = pre-Roman roads

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Both Filippo Coarelli and Simone Sisani recognised that this evidence from the gates of Perusia is not sufficient to establish their hypothesis beyond doubt. They therefore turned to the historical context for further support:

-

✴For Simone Sisani, Via Amerina was extended from Perusia to Iguvium in ca. 283 BC in order to ensure communication between Rome and Sena Gallica, the colony that was founded in the immediate aftermath of the Roman conquest of the ager Galicus.

-

✴For Filippo Coarelli, this putative extension to Iguvium more probably post-dated the conquest of Sarsina in 266 BC, which probably completed the Roman conquest of Umbria. From this point, the extended Via Amerina linked Rome (via Perusia and Iguvium) to both Sena Gallica and Ariminum, a second colony founded in 268 BC on the frontier with Cisalpine Gaul.

However, as discussed below, our earliest evidence for a Roman road from Perusia to Iguvium dates to ca. 700 AD.

Thus, the analysis above only supports the hypothesis for this extension of Via Amerina to Iguvium in the 3rd century BC if Filippo Coarelli is correct in asserting that this was the only reasonable solution to the potential isolation of the colonies that were founded on the Adriatic after the conquest. However, I doubt that this was the case: as Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 283) pointed out, the consular army that defeated the Samnites and Gauls at Sentinum in 295 BC probably first marched:

-

“... to Camerinum, the strong city of their trusty allies [with whom they had agreed ‘foedus aequum’ (equal treaty) in 308 BC]. Camerinum is not merely a place on a road from Umbria to Picenum: it had a connection northwards ... by way of Matilica and Tuficum. Camerinum was clearly the Roman base in the [Battle] of Sentinum”

This northwards stretch crossed a syncline valley to the later site of the municipium of Sentinum, from whence an ancient road along the Misa valley led to the site that was chosen in 283 BC for the colony of Sena Gallica. There are at least two routes by which the Roman army might have approached Camerinum in 295 BC, both of which used the Apennine pass at Plestia (modern Colfiorito):

-

✴via Via Amerina to Ameria and on to Tuder (modern Todi), from whence an ancient road led to Plestia; or

-

✴ via Ocriculum (allied since 308 BC) and Narnia (a colony founded in 299 BC) to Spoletium, and then along an ancient road now known as Via della Spina.

Paolo Camerieri (referenced below) showed both of these routes in his Figure 10 (at p. 102). It seems likely that, after the foundation of a colony at Spoletium in 241 BC, the second of these would have been the more secure of the two routes. After the construction of Via Flaminia in 220 BC, the pass at Plestia would have been conveniently accessed from Forum Flaminii.

In short, it is certainly possible that a Roman road known as Via Amerina reached Perusia at some time in the 3rd century BC. However, I doubt that it reached Iguvium before ca. 593 AD, when, as we shall see, this was the only available route between Rome and the Adriatic.

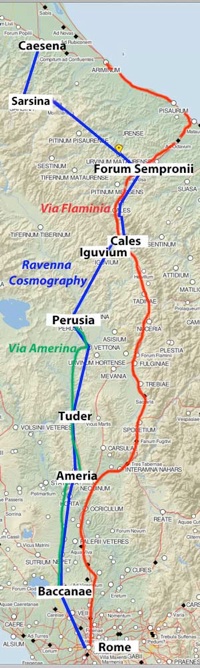

Via Amerina and Ravenna Cosmography

-

“Despite its impressive title, [the Cosmography] was little more than a list of places and regions included in the Empire and in the territory in barbarian hands that had once been part of the Empire. The list is, however, compiled in a way that is anything but casual: the names are listed according to older itineraries and, in many cases, probably according to lists of military centres. ... [Almost all] of the section on Italy reflects contemporary or almost contemporary conditions” (my translation).

The last of the western emperors was deposed in 476 BC, from which time a series of Goths exercised power in peninsular Italy, effectively outside the control of a series of emperors resident in Byzantium. However, as far as we can tell, there was relatively little dislocation. Donald Bullough pointed out (at pp. 214-5) that the Ostrogoth King Theodoric (493-526 AD) chose Spoletium on the Via Flaminia as the administrative centre of central Italy, at which time, in his view:

-

“Via Amerina was still .. a road of minor importance that linked Rome with Perusia ....”

The Byzantines regained control of peninsular Italy in 552 AD, only to lose most of it to the Lombard invaders 16 years later. However, they kept a toe-hold at Ravenna, the seat of the Byzantine exarchs, and a series of popes in Rome continued to acknowledge Byzantine hegemony. The situation stabilised in ca. 593 AD, when the exarch Romanus and Pope Gregory I managed to open up an ‘imperial corridor’ linking Ravenna to the duchies of Perusia and Rome:

-

✴the Lombard kings ruled northern Italy from their capital at Pavia; and

-

✴Spoletium was now the capital of the Lombard Duchy of Spoleto, which included much of modern Umbria.

Crucially, most of Via Flaminia remained in Lombard hands. As Bullough noted (at p. 217):

-

“A road from Ravenna to Rome was reopened, but [now, necessarily] on a new route: precisely that described in the ‘Ravenna Cosmography’” (my translation).

Bullough reproduced (at p. 213) described the itinerary given in the Cosmography from Cesena (on Via Aemilia) to Rome (which I have illustrated in blue on the map to the right). He pointed out (at p. 213) that this itinerary left Via Flaminia at ‘Callis’ (Cales) and continued to ‘Egubio’ (Gubbio), ...

-

“... the main centre on the previously secondary road that linked Perusia to the Via Flaminia ...” (my translation).

From Perusia, it followed the line of:

-

“... the ancient Via Amerina and its northern extension ...” (my translation).