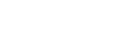

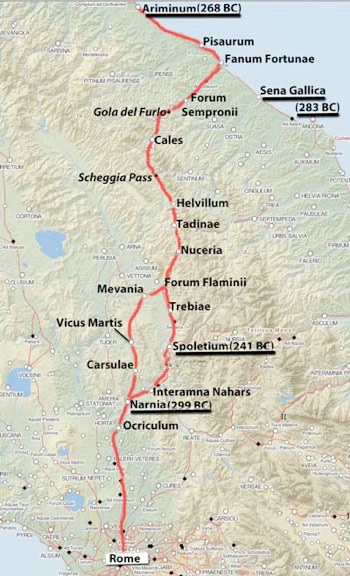

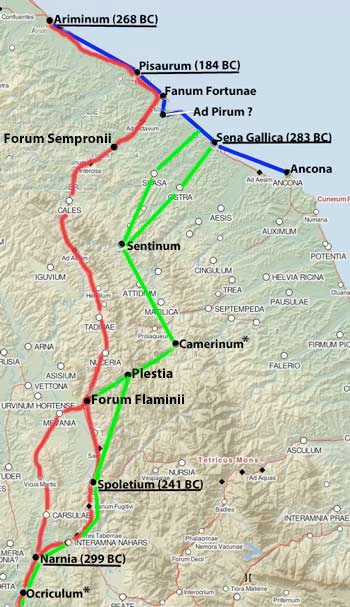

Red = route of Via Flaminia from surviving itineraries

Underlined = Latin Colony (Ariminum, Spoletium and Narnia) or citizen colony (Sena Gallica)

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Peter Wiseman (referenced below), in a paper reviewing what were then (in 1970) a number of new hypotheses relating to the development of the road system of Republican Italy, compiled (at p. 140) a table that summarised the few facts on which such hypotheses could rely: it included unqualified information on only two roads that were constructed in the period before 187 BC:

-

✴Via Appia, which was built by the censor Appius Claudius Caecus in 312 BC, from Rome to Capua (modern Santa Maria Capua Vetere, some 30 km north of Naples); and

-

✴Via Flaminia, which was built by the censor Caius Flaminius in 220 BC, from Rome to Ariminum (Rimini).

There is a good reason why these two early Roman roads are so well documented in our surviving sources: as Thomas Ashby and Roland Fell (referenced below, at p. 125) asserted in their seminal paper on Via Flaminia:

-

“If, for the Romans, Via Appia was the 'queen of roads' [Statius, ‘Silvae’, 2: 2; 12], then Via Flaminia was second to [it: indeed], in some periods, it was more important.”

Having said that, the evidence for Wiseman’s assertion that Via Flaminia was built by the censor Caius Flaminius in 220 BC is not completely clearcut:

-

✴Festus recorded that:

-

“The Circus Flaminius and Via Flaminia were named for the consul Flaminius, who was killed by Hannibal [in 217 BC] beside Lake Trasimene” (‘De verborum significatu quae supersunt cum Pauli epitome’, Part I , p. 63 of the edition published by Emil Thewrewk, my translation).

-

This is sometimes taken to mean that Caius Flaminius built the road in his year as consul for the first time (223 BC). However, it is more likely that Festus mentioned Flaminius’ consulship and the circumstances in which he died simply to differentiate him for other eponymous members of the gens Flaminia, which included his son, the consul of 187 BC.

-

✴Book 20 of Livy’s ‘History of Rome’, which described the circumstances in which Via Flaminia was built, is lost. However:

-

•the surviving summary of it records that, soon after 222 BC:

-

“Censor Caius Flaminius built the Via Flaminia and constructed the Circus Flaminius”, (Periochae, 20); and

-

•two entries in of Book 23 (paragraphs 22 and 23 ), both of which relate to the event of 216 BC, Livy referred back to the time of the most recent censors, Lucius Aemilius Papus and Caius Flaminius.

-

Thus, we can place Flaminius’ censorship within the period 221-217 BC.

-

✴According to Cassiodorus (who was writing in the 6th century AD):

-

“ In the year of [the consuls Lucius Veturius Philo and Caius Lutatius Catullus, i.e. 220 BC], Via Flaminia was paved and the so-called Circus Flaminius was constructed”, (‘Chronica’, 534].

Thus, it is reasonably certain that Caius Flaminius, the consul of 223 and 217 BC, built Via Flaminia as censor in 220 BC.

Similarly, the assertion that Flaminius’ road ran from Rome to Ariminum from its inception is not beyond debate:

-

✴After Flaminius’ defeat at Lake Trasimene in 217 BC, the surviving consul, Cnaeus Servilius Geminus, immediately marched his army from his base at Ariminum towards Rome. Livy recorded that the newly-appointed dictator, Quintus Fabius Maximus, left Rome:

-

“... by the Flaminian way to meet [Servilius] and his army. When, close to the Tiber near Ocriculum, he first caught sight of the column, ... he dispatched an orderly to bid [Servilius] to appear before [him] without lictors [in order to relinquish overall military command. Servilius] obeyed ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 11: 5-6).

-

Thus, we learn that Via Flaminia extended beyond Ocriculum by 217 BC, and that it offered the most rapid route for an army marching from Ariminum to Rome.

-

✴It is entirely possible that Servilius was able to march along Via Flaminia all the way from Ariminum. However, the earliest surviving record that it extended thus far relates to 187 BC: according to Livy, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, one of the consuls of that year:

-

“... ... built a road from Placentia [Piacenza - see the map below] to Ariminum, in order to make a junction with Via Flaminia”, (‘History of Rome’, 39: 2: 5-10).

As we shall see, we know very little about the original course of Via Flaminia between Ocriculum and Ariminum, albeit that we might reasonably assume that Forum Flaminii (north of modern Foligno) was named for Caius Flaminius and that it was founded on Via Flaminia in or soon after 220 BC. Beyond that, we have the evidence of five surviving itineraries (discussed below), but it is important to bear in mind that even the earliest of these probably post-dated the Augustan restoration of the road in 27 BC:

-

✴All of these itineraries have the road:

-

•continuing north from Ocriculum as far as Narnia (Narni); and

-

•running north from Forum Flaminii; crossing the Apennines through the Gola del Furlo; meeting the coast at Fanum Fortunae (Fano); and continuing along it to Ariminum.

-

✴However:

-

•while the earliest of them have the road from Narnia to Forum Flaminii passing through Mevania (Bevagna);

-

•some of those from the 4th century AD describe a slightly longer and more difficult eastern route that passed through Spoletium (Spoleto).

Both of these routes are marked on the map above. Ashby and Fell (referenced below, at pp. 132-3) estimated the distances from Rome to Ariminum at:

-

✴ 209 Roman miles (310 km) via Mevania; and

-

✴ 215 Roman miles (319 km) via Spoletium.

Caius Flaminius (Consul 223 and 217 BC)

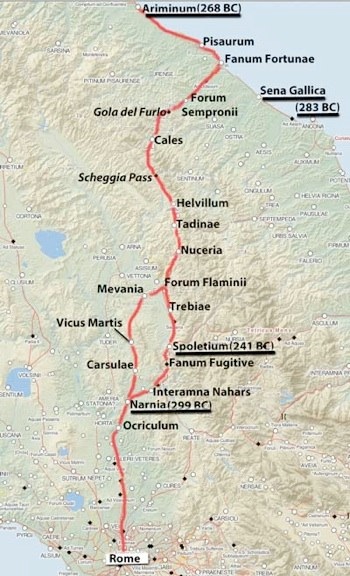

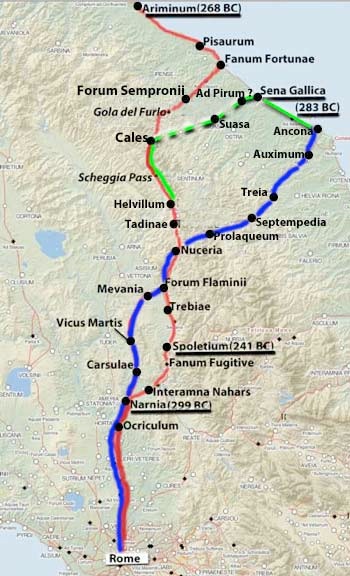

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Green line = Via Flaminia (220 BC), following the route described in imperial itineraries

Placentia and Cremona = Latin colonies founded in 218 BC

Ashby and Fells (referenced below, at p. 126) asserted that:

-

“... however much of the northern highway [from Rome to Ariminum] was already in use [in 220 BC], it owed its establishment as a permanent possession of the Roman state to Caius Flaminius, with whose policy ... it was intimately connected.”

This, of course, presupposes that Flaminius had a policy, and that he was in a position to pursue it as an individual. As discussed below, it is probably safer to place the building of Via Flaminia in the context of more widely-shared political objectives that can be conveniently explored by following Flaminius’ career.

Lex Flaminia Agraria (232 BC)

The earliest reference in the surviving sources to Flaminius relates to 232 BC, when he was a tribune of the plebs and was on his way to becoming the first member of his family to attain the consulate. According to Polybius, in that year:

-

“... the Romans divided among their citizens [that part of] the territory of Picenum from which they had ejected the [the Gallic tribe known as] the Senones. Caius Flaminius was the originator of this popular [i.e. pro-plebeian] policy ... ”, (‘Histories’, 2: 21).

Expulsion of the Senones (283 BC)

The Romans had ejected the Senones from their territory between the Apennines and the Adriatic in 283 BC, at which point it had become the Roman ager Gallicus. Polybius recorded that, soon after:

-

“... the Romans sent the first colony that they ever planted in Gaul: namely, ... Sena [Gallica], so called from the tribe of Gauls that had formerly occupied it”, (‘Histories’, 2: 19).

Livy (‘History of Rome’, 27: 38: 4) listed Sena Gallica among 7 maritime citizen colonies that, in 207 BC, pleaded their exemption from prolonged military duties elsewhere. Such colonies seem generally to have been small. However, Giuseppe Lepore (referenced below, in the abstract at p. XVII-XVIII) pointed out that recent excavations at Sena Gallica suggest that:

-

“... this first maritime colony on the Adriatic seems to have had the shape and size of a Latin colony, anticipating what would happen 20 years later at the [Latin] colony of Ariminum” (my translation).

Thus, it seems likely that Sena Gallica was planned primarily for the purpose of accommodating a significant number of Roman colonists in the newly-confiscated territory.

Foundation of the Colony of Ariminum (268 BC)

As noted above, the Latin colony of Ariminum to which Lepore alluded was to become the end-point of Via Flaminia. It had been founded in 268 BC on land that (as we shall see) was claimed by the Boii, which was one of a number of Gallic tribes that had settled in the region north of the Apennines that the Romans knew as Cisalpine Gaul (as opposed to Transalpine Gaul, north of the Alps). Stephen Dyson (referenced below, at p. 27) characterised the foundation of Ariminum as:

-

“... a turning point in Romano-Gallic relations: previously, Roman and the largest Gallic tribes had had only indirect frontier contacts, but now the Romans had moved several thousand settlers into territory that the Gauls had considered as their own for [at least] a century.”

From this point, the northern border of Roman territory ran across the Apennines from Ariminum in the east to the territory of an Italic tribe, the Ligurians, in the west, facing the territory of the Gallic Boii and Insubres who were settled in the valley of the Padus (Po).

Polybius characterised Flaminius’ law as:

-

“... a democratic [i.e. pro-plebian] measure ...[that] we must pronounce to have been the first step in the demoralisation of the [Roman] people”, (‘Histories’, 2: 21).

Cicero (more than a century after Polybius) often made the same accusation. For example:

-

“Caius Flaminius, ... when he was tribune of the people, proposed to the people, in a very seditious manner, an agrarian law against the consent of the Senate, and altogether against the will of all the nobles”, (‘De inventione’, 2: 52).

Thus, like many scholars, Ashby and Fells (referenced below, at pp. 126-7) asserted that:

-

“[Flaminius’] policy, like that of other democratic leaders at Rome, was ... [probably] aimed at extending the Roman frontier to the Alps ... and peopling the Po valley with citizen settlers. What Rome had conquered was to be used for the benefit of the mass of Roman citizens, and the distribution ager Gallicus was a provision for the poor of the city.”

However, one wonders whether Flaminius’ actions here were as controversial as Polybius and Cicero claimed: as Rachel Feig Vishnia (reference below, 2012, at pp. 40-1) pointed out:

-

“It is reasonable to assume that ... he did not launch his agrarian law on his own, but was [instead] a member of a group that...[ must have included] senior senators. ... [Although Flaminius’] opponents [among the optimates] strongly opposed the law, ... it should be stressed that none of the [surviving] sources specifically states that the Senate eventually voted against it, or that Flaminius took it to the people over the Senate's head. ... The law passed and, most probably, a body of 15 land commissioners that included high ranking senators (and naturally Flaminius as well) was elected [to implement it].”

In the same vein, Daniel Gargola (referenced below, at p. 104) pointed out that Flaminius’ agrarian law was one of three for which we have information in the period 232-173 BC: the other two related to land distribution in (respectively): Apulia and Samnium, in 201 BC; and Liguria and [Cisalpine] Gaul in 173 BC. He observed that, although the distribution of 232 BC is the only one for which we have an explicit reference to a plebiscite, there is no reason to think that the procedure here differed materially from that followed in the other two cases. He suggested that some of the later accounts might well have been embellished by hindsight, pointing out that they depict Flaminius:

-

“... in the guise of a typical demagogue ... One act expected from a popular leader [of this kind], especially from those [like Cicero, who were] writing after the reforms of the Gracchi, was the passage of an agrarian law against the will of the Senate ... Despite the rhetorical and political [tone] of many of these accounts, the descriptions of the actual provisions of the lex Flaminia agraria [indicate that they were] consistent and reasonable.”

Rachel Feig Vishnia (reference below, 2012, at pp. 40-1) therefore offered the more nuanced suggestion that Flaminius and supporters believed:

-

“... that the ager Gallicus..., which remained [at least to some extent] uninhabited ... should be settled, in order:

-

✴to provide lands for Roman farmer-soldiers who had lost their lands [during prolonged military service] ...; and

-

✴to establish a properly-manned zone on the northeastern border with the Boii ...”

Flaminius as Consul in 223 BC

The years following Flaminius’ agrarian law saw a further consolidation of the Romans’ sphere of influence:

-

✴In 229-8 BC, they fought the First Illyrian War, after which they established a presence along the eastern coast of the Adriatic (in modern Montenegro).

-

✴Meanwhile, the Carthaginians had been building up a considerable presence in Hispania (modern Spain and Portugal). The Carthaginian had first established a significant presence there after the First Punic War and the subsequent Roman annexation of Sardinia and Corsica.

-

•The Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca, who had begun this initiative in 237 BC, had died in ca. 229 BC.

-

•His son-in-law and successor, Hasdrubal, continued this process of expansion, creating a new capital at Carthago Nova (New Carthage, modern Cartagena). Polybius reported that, in 226 BC, the Romans:

-

“... [sent] envoys to Hasdrubal, and [made] a treaty with him, by which the Carthaginians ... engaged not to cross the[Ebro] in arms”, (‘Histories’, 2: 13).

Polybius then noted that the Romans were now free to concentrate of the resurgent threat from the Gauls. This involved a major war in 225 BC, followed by a period of three years in which both consuls undertook further campaigns in Cisalpine Gaul. As we shall see, it was in this context that Flaminius, one of the consuls of 223 BC, was awarded a triumph.

Gallic Invasion (225 BC)

Troop movements leading to the Battle of Telamon (225 BC)

Red= Roman; blue = Gauls

Adapted from the map in this webpage by Karwansaray Publishers

In or shortly before 225 BC, the Insubres and the Boii (the two Gallic tribes settled closest to Rome) recruited a number of mercenaries from Transalpine Gaul in preparation for an invasion of Roman territory. When the Romans became aware of this, one of the serving consuls, Lucius Aemilius Papus, was stationed at Ariminum: clearly, the Romans thought that the Gallic army would attempt to take Ariminum before crossing the Apennines by one of the mountain passes that could be reached from the Adriatic coast. However, the invaders marched across one of the passes west of Ariminum into Etruria and reached Clusium (Chiusi) before the Roman force that was supposed to have defended against this contingency could catch up with them. Aemilius managed to reach Clusium in time to avert defeat, and the Gauls fell back on the coastal centre of Telamon, with Aemilius in pursuit. Meanwhile, his colleague, Caius Atilius Regulus, who had been campaigning in Sardinia, landed at Pisae (Pisa) and marched south along the coast to join the fray. The Gauls were comprehensively defeated in this pincer movement, albeit that Atilius was killed in the battle. Thus, the Fasti Triumphales record that Aemilius was awarded a triumph over the Gauls in 225 BC. As Polybius observed:

-

“Thus was the most formidable Gallic invasion repelled, which had been regarded by all Italians, and especially by the Romans, as a danger of the utmost gravity. The victory inspired the Romans with a hope that they might be able to entirely expel the Gauls from the valley of the Padus [Po]”, (‘Histories’, 2: 31: 8).

In my view, it is more likely that this campaign inspired in the Romans a desire to reinforce their precarious northern border, whether or not this required the expulsion of the Gallic tribes who inhabited the Po valley.

Aftermath of the Invasion

In the following three years, the Romans concentrated on pressing home their advantage in Cisalpine Gaul:

-

✴The consuls of 224 BC, Quintus Fulvius Flaccus and Titus Manlius Torquatus, secured the submission of the Boii. According to Arthur Eckstein (referenced below, at p. 15):

-

“Apparently, the consuls exacted an ... absolute surrender and demanded hostages as assurances for future good behaviour. [It was probably at this point that the Boii were] forced to give the Romans certain territory in the northwest corner of their lands for the Latin colony of Placentia [see below]. ... Especially when one considers the leading role of the Boii in the invasion of 225 BC, ... this seems a moderate settlement ... : their freedom of action was somewhat hindered by Roman possession of Boian hostages, but the Boii were still left ... in possession of most of their land.”

-

✴The consuls of 223 BC, Caius Flaminius and Publius Furius Philus, then defeated the Insubres in the Po valley: the Fasti Triumphales record that both consuls were awarded triumphs:

-

•Flaminius against the Gauls (as noted above); and

-

•Furius against both the Gauls and the Ligurians.

-

The Romans, however, remained intent on total submission, and the Insubrians’ request for peace was denied.

-

✴The consuls of 222 BC, Marcus Claudius Marcellus and Cnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus, pressed on to total victory. Arthur Eckstein (referenced below, at p. 15, note 46) suggested that it was at this point that the Romans acquired the land for the Latin colony of Cremona [see below]. He noted (at p. 18) that, more generally, this was a relatively modest settlement that left the Insubres in possession of most of their land. Marcellus seems to have secured credit for the victory: thus, the Fasti Triumphales record his triumph over the Insubrian Gauls and the ‘Germans’, adding that he brought back the spolia opima after killing the enemy leader, Virdumarus, at Clastidium.

Thus, in 222 BC, it must have seemed to the Romans that the task of pacifying the Boii and Insubres on their northern border was complete.

Flaminius as Censor in 220 BC

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

The evidence that Flaminius and Lucius Aemilius Papus served as censors in 220 BC is set out above. Unfortunately, Book 20 of Livy’s ‘History of Rome’, which covered this period, is lost: the surviving summary records that:

-

“[In the period following 220 BC]:

-

✴The Istrians were subdued.

-

✴The Illyrians revolted again, but were subdued. Their surrender was accepted.

-

✴Three times, the censors [Flaminius and Aemilius] celebrated the lustrum ceremony. On the first occasion, 270,212 citizens were registered. Freed slaves were registered in four voting districts: Esquilina, Palatina, Subura, and Collina. Until then, they had been divided more equally: [by concentrating them in the four urban tribes, which were larger than the 31 rural tribes, their influence would have been reduced].

-

✴Censor Gaius Flaminius built the Via Flaminia and constructed the Circus Flaminia [as discussed above].

-

✴Colonies were founded in the conquered Gallic territories, at Placentia and Cremona”, (Periochae, 20).

However, these events should probably be considered in the light of the ‘elephant in the room’ (and the subject of the opening part of Livy’s Book 21): Rome’s relations with Hasdrubal’s successor in Hispania, Hannibal Barca.

Hannibal

Livy devoted Book 21 to:

-

“... the most memorable of all wars ever waged”, (‘History of Rome’, 21: 1: 1).

This was the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), in which (as mentioned above) Flaminius, among others, met his death at the hands of Hannibal’s army.

This war (discussed in detail in the following page) was triggered by events in Hispania:

-

✴The Carthaginian had first established a significant presence there under Hannibal’s father, Hamilcar, in 237 BC, after the First Punic War and the subsequent Roman annexation of Sardinia and Corsica.

-

✴When Hamilcar died in ca. 229 BC, his son-in-law and successor, Hasdrubal, continued this process of expansion, creating a new capital at Carthago Nova (New Carthage, modern Cartagena). As mentioned above, Polybius reported that, in 226 BC, the Romans:

-

“... sent envoys to [the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal and made a treaty with him by which the Carthaginians ... agreed not to cross the river Ebro in arms...”, (‘Histories’, 2: 13).

-

✴The young Hannibal had accompanied his father to Hispania and had continued to serve there under Hasdrubal. When Hasdurbal was assassinated in 221 BC, his command passed to Hannibal.

Northern Adriatic

One version of the Roman wars against the Istrians and Illyrians after 222 BC (the first two items in the summary above) is given by Zonaras:

-

“Later [Publius Cornelius Scipio Asina and Marcus Minucius Rufus, the consuls of 221 BC] made an expedition in the direction of t[Istria] and subdued many of the nations there, some by war some by capitulation. [Lucius Veturius Philo and Quintus Lutatius Catullus, the consuls of 220 BC] went as far as the Alps, and without any fighting won over many people. But ... Demetrius [of Pharos, the ruler of the Illyrian tribe known as the Ardiaei] ... was ... abusing the friendship of the Romans that he was able to wrong [his neighbours]. As soon as the consuls[of 219 BC, Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Marcus Livius Salinator], heard of this, ... they made a campaign against him ... [He] made his escape to Pharos, [which the Romans then captured], though only after [he] had fled. This time he reached [Philip V of] Macedonia ... on returning to Illyria, he was arrested by the Romans and put to death” (‘Epitome of Cassius Dio, Book 12’, 8:20).

However, Gareth Sampson (referenced below, at pp 195-8) suggested that Appian (‘Illyrian Wars’, 2: 8) might have been correct when he associated Demetrius of Pharos with both campaigns. In other words, the campaign to reassert the Romans’ control of the northern Adriatic might have extended across the whole period 221-219 BC, albeit that the consuls of 220 BC apparently spent much of their time in securing allies on their northern border.

Via Flaminia and the Colonies at Placentia and Cremona

As noted above, Flaminius began the construction of Via Flaminia as censor in 220 BC. It seems likely that this project should be seen in the context of the Romans’ consolidation of their northern border, alongside:

-

✴the campaigns of 221-19 BC in Istria and Illyria;

-

✴the diplomatic activity of the consuls of 220 BC, Lucius Veturius Philo and Quintus Lutatius Catullus, in Cisalpine Gaul; and

-

✴the decision to found the Latin colonies of Placentia and Cremona, albeit that the implementation of this decision, at least in the case of Placentia, was still in progress in 218 BC.

Rachel Feig Vishnia (referenced below, at p. 24) noted that:

-

“On the eve of the Second Punic War, Rome had just barely begun to consolidate her newly acquired domains. Hannibal’s impressive advance in [Hispania] during 221-20 BC and the growing tensions [there] ... do not seem to have concerned Rome significantly. Her efforts were centred on safeguarding the vast territories that she now controlled in the north. Thus:

-

✴in 221 BC, [the Romans] fought against the Istrians , who were intercepting [Roman shipping] in the norther Adriatic ... ([‘Breviarium ab urbe condita’, 3:7];

-

✴in 220 BC, both consuls [Quintus Lutatius Catulus and Lucius Veturius Philo] ‘went as far as the Alps, and without any fighting, won over many people’ [Zonarus, ‘Epitome of Cassius Dio’, 8:20)]; and

-

✴in 219 BC, probably after the Roman [legates] returned from Hispania and Carthage, [the consuls Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Marcus Livius Salinator defeated Demetrius of Pharos in the Second Illyrian War].”

In relation to the activities a gainst the Istrians and Illyrians, she observed that:

-

“Rome could not countenance any piratical activity, real or imagined, in the northern Adriatic at a time when Ariminum, the key to Cisalpine Gaul, was becoming an important military and civil harbour and when the coastal part of Via Flaminia ... was being constructed.”

With hindsight, the Roman decision to send two consuls against Demetrius of Pharos in 219 BC while offering no help to the Saguntines can be seen as a disastrous mistake. Thus, Livy attributed the following words to Publius Sulpicius Galba, in a speech in 200 BC in which he argued that war should be declared against Philip V of Macedon, who had injured allies of Rome:

-

“It seems to me, citizens, that you do not realise that the question before you is not whether you will have peace or war ... but rather whether you are to [fight in] Macedonia or ... in Italy. You found out what a difference that makes ... in the recent Punic war, ... when the Saguntines were besieged and were invoking our protection. For, who doubts that, ... had we promptly sent aid to them, ... we should have diverted the whole war to Spain? Instead, by our delay, we admitted it to Italy, with infinite losses to ourselves?”, (‘History of Rome’, 31: 7).

However, in 219 BC, Hannibal had not violated the treaty of 226 BC by crossing the Ebro: his only ‘offence’ had been to ignore the arguably high-handed Roman demand that he should not attack Saguntum.

Via Flaminia during the Second Punic War (218-201 BC)

In 219 BC, Hannibal laid siege to Saguntum, the only significant Hispanic city south of the Ebro that remained independent of Carthage. The Romans threatened war on the grounds that Saguntum enjoyed their protection, but then did nothing to relieve the siege. Saguntum held out for eight months or more, but succumbed in 218 BC. The Romans sent legates to Carthage with an ultimatum : when this was rejected, they formally declared war, by which time (the summer of 218 BC) Hannibal was already marching towards (and might well have crossed) the Ebro.

The Romans consequently accelerated foundation of the Latin colonies at Placentia (Piacenza)and Cremona (marked on the map above). The Boii, who were encouraged by news of Hannibal’s advance, rose in rebellion, and the army that was about to leave for Hispania under the consul Publius Cornelius Scipio (the father of Scipio Africanus) had to be sent instead to Cisalpine Gaul. By the time that Scipio arrived on the Rhone at the head of a new army, he found that Hannibal had already crossed the river and was headed for the Alps: he sent his army on to Hispania, but he took ship for Pisae (Pisa). Hannibal duly crossed the Alps and marched into Italy in the winter of 218 BC and secured the allegiance of the Insubres:

-

✴In November, he confronted Scipio and another new army on the Ticinus river. He had the best of the fighting, but the Romans were able to retreat to Placentia, taking the wounded Cornelius with them.

-

✴The other consul, Tiberius Sempronius Longus, who had also been called back to Italy from Sicily, landed at Ariminum and joined forces with Scipio. Hannibal was able to draw Sempronius’ army into an ambush between the Trebbia and the Po. Again, he had the best of the fighting, but Sempronius was able to fall back on Placentia.

Thus the Romans’ hard-won control of the Po valley had proved to be illusory, and the threat of a Carthaginian invasion of Rome itself was very real indeed.

Red line: probable route of Hannibal’s march to Lake Trasimene (217 BC)

Blue line: Via Flaminia

Adapted from a map in the website ‘Indian Defence’

In the following year (217 BC), Caius Flaminius was elected consul for the second time. According to Livy, the Senate ordered him to take charge of the army at Placentia after his ritual inauguration in Rome. However, he:

-

“... [stole] away furtively [from Rome] without his insignia of office, and without his lictors ... He [apparently thought it] more consonant with the greatness of his office to enter upon it at Ariminum rather than in Rome, and to put on his official dress in some wayside inn rather than at his own hearth and in the presence of his own household gods. ... [Once this extraordinary inauguration was complete,] Flaminius took over the two legions [that he had sent for from Placentia] ... and commenced his march to [Arretium (Arezzo)] through the passes of the Apennines”, (‘History of Rome’, 21: 63: 9-14).

Although Livy does not say so, it seems likely that Flaminius’ march from Rome to Ariminum had been a celebration of the recent completion of his new road, and that this was the route taken by his consular colleague, Cnaeus Servilius Geminus, who (after his traditional inauguration in Rome) marched his army to Ariminum. The purpose of stationing Flaminius at Arretium and Servilius at Ariminum would have been to defend the two most likely points at which Hannibal might try to cross the Apennines.

Any sense of achievement that Flaminius had felt during his march to Ariminum was quickly dispelled: Hannibal crossed the Apennines and managed to bypass his camp at Arretium. When Flaminius marched after him, Hannibal famously ambushed him of the shores of Lake Trasimene: Flaminius and most of his men died in action, soon followed by a cavalry detachment that Servilius had sent to Flaminius’ aid. Rome was now potentially at Hannibal’s mercy.

Servilius was ordered back to Rome, where Quintus Fabius Maximus had been appointed as dictator to deal with the emergency. Fabius went out to meet Servilius in order to assume overall command: he left Rome:

-

“... by the Flaminian way ... and when, close to the Tiber near Ocriculum (Otricoli), he first ... saw [Servilius] riding towards him at the head of his cavalry, he... [summoned him] to appear before him without lictors. [Servilius] obeyed ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 11: 5-6).

From these accounts, we learn that Via Flaminia entered Umbria at Ocriculum and that it had probably reached Ariminum by 217 BC.

Extension to Placentia (187 BC)

Blue = Via Flaminia (220 BC); Yellow = Via Aemilia (187 BC); Purple = Via Cassia (171 BC?, 154 BC?)

Underlined = colonies

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

We next hear of Via Flaminia in 187 BC, by which time the the menace from Carthage had been overcome and Boii had been finally defeated. The consuls of 187 BC, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus and Caius Flaminius (the son of the consul who had built Via Flaminia), pacified a number of Ligurian tribes (whose territory was in northwestern Italy, north of Pisae (Pisa). Thereafter:

-

“... so that he might not leave his army idle, Flaminius built a road from Bononia [Bologna] to Arretium. The other consul, Marcus Aemilius, ... led his army into Gallic territory and built a road from Placentia [(Piacenza)] to Ariminum, in order to make a junction with the Via Flaminia”, (‘History of Rome’, 39: 2: 5-10)

The Via Aemilia is well-documented in our surviving sources, and Livy’s account confirms the fact the fact that Via Flaminia had reached Ariminum by 187 BC (if not, before). However, there is no surviving evidence that corroborates Livy’s assertion that the younger Flaminius built a road from Bononia to Arretium at this time.

Strabo gave an amplified version of the road-building projects of the consuls of 187 BC: having referred first to a later Via Aemilia (which had been built by Marcus Aemilius Scaurus), he recorded that

-

“... there is another Aemilian Way ...: I mean the one which succeeds [i.e, continues] the Flaminian. For Marcus [Aemilius] Lepidus and Caius Flaminius were consuls together: upon subjugating the Ligures:

-

✴[Flaminius] constructed the Flaminian Way from Rome ... as far as the regions of Ariminum; and

-

✴[Aemilius constructed] the succeeding [i.e. continuing] road, which runs as far as Bononia and, from there, [continues] along the base of the Alps, thus encircling the marshes, to Aquileia”, (‘Geography’, 5: 1:11).

Most scholars believe that Strabo confused the road that the younger Flaminius built in 187 BC with the road that his father had built from Rome to Ariminum in 220 BC (as discussed further below). (Furthermore, there is no other surviving evidence that corroborates Strabo’s assertion that Aemilius Lepidus was responsible for a road that ran ‘along the base of the Alps’ to Aquileia.) However, Strabo’s account agrees with that of Livy in one important respect: Via Flaminia certainly reached Ariminum in 187 BC (albeit that there is no other surviving evidence that any part of it had been built by the younger Flaminius).

Augustan Restoration (27 BC)

In his autobiography, the Emperor Augustus (27BC - 13AD) recorded that:

-

“As consul for the 7th time (i.e. in 27 BC), I made the Via Flaminia from [Rome] to Ariminum, and all the bridges except the Mulvian [across the Tiber] and the [otherwise unrecorded] Minucian”, (‘Res Gestae Divi Augusti’, paragraph 20).

Cassius Dio elaborated:

-

“...perceiving that the roads outside the walls [of Rome] had become difficult to travel as the result of neglect, [Augustus] ordered various senators to repair the others at their own expense, and he himself looked after Via Flaminia, since he was going to lead an army out by that route. This road was finished promptly at that time, and statues of Augustus were accordingly erected on arches on the bridge over the Tiber and at Ariminum”, (‘Roman History’, 53:22).

This major restoration was part of the ‘peace dividend’ after the victory of Octavian (soon-to-become the Emperor Augustus) over Mark Antony at Actium in 31 BC) which had marked the end of decades of civli war. The arches that Augustus erected at the start and the end of the newly-restored Via Flaminia memorialised his triumph (which had marked the end of the Roman Republic).

Route of Via Flaminia

Red = route of Via Flaminia from surviving itineraries

Underlined = Latin Colony

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

As note above, Via Flaminia:

-

✴entered Umbria at Ocriculum from its inception; and

-

✴terminated at Ariminum by 187 BC, if not before.

However, it is important to note that we have no early evidence for the route that it took between these two points.

Strabo (probably late 1st century BC)

Strabo, in the ‘Geography’, listed the cities of Umbria in relation to Via Flaminia. According to Duane Roller (referenced below, in Section 1):

-

“It is not known when [he] began to write the ‘Geography’, but his own statement that it followed the completion of his ‘Historical Commentaries’ ... suggests that he might have begun [it] by the end of [the 20s BC], ... [However,] he continued [working on it] for many years, until his death in the 20s AD. Much of his research may have been earlier rather than later in this period, yet he updated the treatise as long as he was able, [albeit] not consistently.”

Earlier in this section, he noted that:

-

“Strabo probably returned to Rome a number of times. ... he refers [inter alia] to the Mausoleion of Augustus, so [this account] was written either during or after its construction (28-23 BC).”

On the basis of these observations, we might reasonably assume that Strabo’s account of the route of Via Flaminia, which is probably the earliest of those that survive, post-dates its Augustan restoration.

According to Strabo:

-

"The [Umbrian] cities on [the western] side the Apennines that are worthy of mention are:

-

✴First, on the Flaminian Way itself:

-

-Ocricli [Otricoli], near the Tiber;

-

-Narnia [Narni], through which the Nar River flows ...;

-

-Carsuli [now the archeological area of Carsulae]; and

-

-Mevania [Bevagna], past which flows the Teneas .... .

-

✴[There are] still other settlements [on this road] that have become [settled] on account of the Way itself rather than [as a consequence] of political organisation; these are:

-

-Forum Flaminium [Forum Flaminii, discussed below];

-

-Nuceria [Nocera Umbra]...; and

-

-Forum Sempronii, [Fossombrone].

-

✴Secondly, to the right of the road as you travel [north] from Ocricli ... are:

-

-Interamna [Terni];

-

-Spoletium [Spoleto]; and

-

-Aesium [Assisi] …

-

✴On the other side of the road [stand]:

-

-Ameria [Amelia];

-

-Tuder [Todi] , a well-fortified city;

-

-Hispellum [Spello]; and

-

-Iguvium [Gubbio], the last-named lying near the passes that lead over the [Apennines]”, (‘Geography’, 5: 2:10).

Thus, it seems that only the western branch through Mevania was considered to belong to Via Flaminia at the time at which Strabo was writing: the eastern branch through Interamna Nahars and Spoletium was considered to be to the east of Via Flaminia proper.

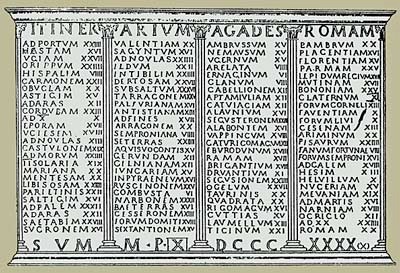

Itinerarium Gaditanum on the Vicarello Cups (ca. 1st century AD)

CIL XI 3281 (from the website by the Biblioteca Augustana der Fachhochschule, Augsburg)

In 1852, four silver cups that are now in the National Roman Museum, Rome were found at Vicarello, in northern Italy (illustrated on Flickr by Ryan Baumann). Each is inscribed with a list of the way stations on the roads between Rome and Gades (Cadiz), with the distances between them: this itinerary is known as the ‘Itinerarium Gaditanum’. The four inscriptions span a considerable period of time: CIL XI: 3284, (early imperial period); 3283, (ca. 40 AD); 3282, (ca. 50 AD); and 3281 (ca. 200 AD), but even the earliest of them is probably slightly later than that of Strabo (above). In each case, the final part of the route (at the lower right) follows Via Flaminia:

-

✴in the ager Gallicus:

-

•Ariminum; Pisaurum; Fanum Fortunae; Forum Sempronii;

-

✴in Umbria:

-

•Ad Calem (Cales, modern Cagli) Hesim (probably Ad Aesim, modern Scheggia); Helvillum (near modern Fossato di Vico); Nuceria; Mevania; Ad Martis (a way station near modern Massa Martana); Narnia; Ocriclo; and

-

✴finally, Rome.

In the Umbrian section, we find a more detailed account than Strabo’s of the western branch, albeit that Carsulae is missing.

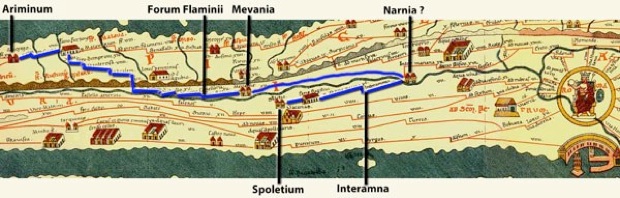

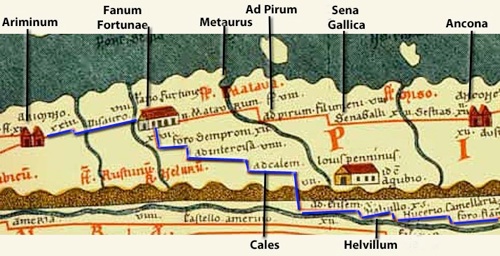

Tabula Peutingeriana (ca. 300 AD)

Tabula Peutingeriana (from the website by the Biblioteca Augustana der Fachhochschule, Augsburg)

Via Flaminia in blue

‘Tabula Peutingeriana’ is the name given to a copy that was made in Worms in the 13th century of an illustrated set of itineraries across western Europe: this copy, which was first published in 1591, was named for Conrad Peutinger, the German humanist who acquired it in the 16th century. Richard Talbert (referenced below, 2010, at p. 134) pointed out that the original must have post-dated the Roman annexation of Dacia in the early 2nd century BC. He also suggested (at pp. 135-6) that its lack of any Christian emphasis suggests that it pre-dated the sole rule of the first Christian emperor, Constantine I, which began in 324 BC: Talbert noted, at p. 391, note 11, that Constantinople, which Constantine founded in 330 AD, had been subsequently added to the map. He suggested (at p. 136) that:

-

“... the map’s design and presentation best match Diocletian’s Tetrarchy (ca. 300 AD).”

The Tabula does not illustrate the stretch of Via Flaminia from Rome: the illustrated itinerary begins at an unlabelled city that must be Narnia:

-

✴The western branch in Umbria is shown in its entirety from Narnia via Mevania to Forum Flaminii, and this road continues through:

-

•Nuceria, Helvillum and Ad Aesim and Cales in Umbria;

-

•Forum Sempronii, Fanum Fortunae, Pisaurum and Ariminumin the ager Gallicus.

-

✴The eastern branch from Narnia is illustrated only as far as Spoletium: there is no indication here that it continued to Forum Flaminii. In the illustrated stretch, it passed through Interamna Nahars and Fano Fugitivi (which was probably a shrine at la Somma, the highest point on the entire length of the road).

Antonine Itinerary (ca. 300 AD)

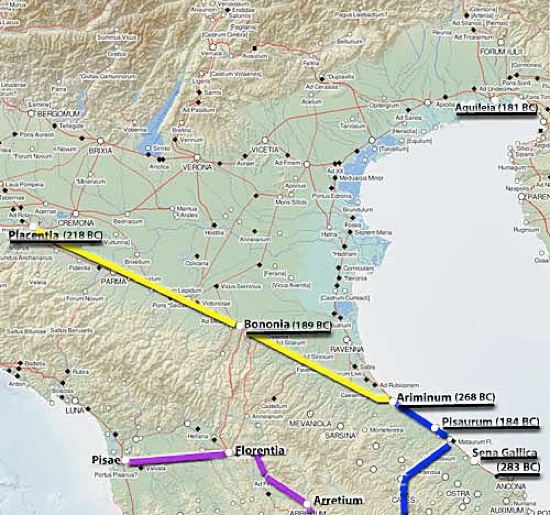

Via Flaminia in the Antonine Itinerary (reproduced by Richard Talbertt (referenced below, 2010):

Red = route described at p. 221, 124:8 - 126:4

Blue = route described at p. 246, 311:1 - 312:6

Green = route described at p. 247, 315:7 - 316:5; dotted section uncertain

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Richard Talbert (referenced below, 2007, at p. 256) observed that:

-

“From the Middle Ages onwards, the anonymous collection misnamed the Antonine Itinerary (Imperatoris Antonini Augusti itineraria provinciarum et maritimum) has consistently attracted attention. ... It seems fair to claim that, after a long debate, a broad consensus has now been reached about certain basic features of the collection: in particular:

-

✴that it assembles individual itineraries of distinctly varied character and perhaps even [of various] dates;

-

✴that it was complied in ca. 300 AD; and

-

✴that, despite the traditional title, there is no secure connection to travel by emperors.”

He also noted (at p. 263) that:

-

“At least some of the ‘backbone’ itineraries were no doubt ‘official’ Roman reference documents ...”

Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, at p. 75), suggested that the part of the collection relevant to the present discussion:

-

“... was compiled ... on the basis of a census of the urban centres of the Empire and the distances between them, along the principal thoroughfares [such as Via Flaminia] ....” (my translation).

Richard Talbert (referenced below, at pp. 206-70) reproduced the entire itinerary, and it is also reproduced in this website. It contains two routes that are directly relevant to the current discussion:

-

✴Under the broad heading ‘Italia’ (at 98:2), an itinerary (at 124:8 - 126:4) ran from Rome through:

-

•Otricoli, Narnia, Interamna Nahars, Spoletium, Forum Flaminii, Helvillum and Cales, all in Umbria; and

-

•Forum Sempronii, Fanum Fortunae, and Ariminum, all in the ager Gallicus.

-

This route is shown in red on the map above.

-

✴Under the heading ‘Flaminia’ (at 310:5), an itinerary ran from Rome through:

-

•Otricoli, Narnia, Ad Martis, Mevania and Nuceria, all in Umbria (311: 1-5); and

-

•Prolaqueum (Pioraco), Septempeda (San Severino), Treia, Auximun (Osimo and Ancona, all in Picenum (312: 2-6).

-

This route is shown in blue on the map above.

This is the earliest surviving evidence of the coexistence of the western and eastern branches of Via Flaminia over the whole distance from Narnia to Forum Flaminii.

The Antonine Itinerary also includes a route under the heading ‘Ab Helvillo Anconam’ (at 315:7 - 316:5, shown in green on the map above) from Helvillum and Cales on Via Flaminia that then crossed the Apennines and ran along the Cesano valley to Sena Gallica and continued southeastwards along the coast to Ancona :

-

✴Helvillum - Cales 50 Roman miles

-

✴Cales - Ad Pirum 14 Roman miles

-

✴Ad Pirum - Sena Gallica 8 Roman miles

-

✴Sena Gallica - Ancona 20 Roman miles.

Tabula Peutingeriana (from the website by the Biblioteca Augustana der Fachhochschule, Augsburg)

Via Flaminia in blue

Fortunately, a visual indication of the location of ‘Ad Pirum’ survives in the the Tabula Peutingeriana, which locates ‘Ad Pirum Filumeni’ 8 Roman miles (12 km) west of Sena Gallica, and the same distance east of the Metaurus river (on a road that continued north to meet Via Flaminia at Fanum Fortunae). Federico Uncini (referenced below. at pp. 38-9) suggested that these mileages suggest that it was a little way from the coast, at modern Mondalfo in the Cesano valley.

-

✴Uncini noted (at p. 39) that, on this basis:

-

“The distance from Cales to Ad Pirum given in the Antonine Itinerary is incorrect, perhaps due to an erratic transcription” (my translation).

-

✴This is also true of the distance given for Helvillum to Cales: the correct value (23 Roman miles) is given at 125:7.

This uncertain stretch between Cales and Sena Gallica marked by a dotted green line in the map at the start of this section.

Itinerarium Burdigalense (333 AD)

This itinerary (also known as the Itinerarium Hierosolymitanum), which was written in 333 AD by a pilgrim traveling from Bordeaux to Jerusalem, includes a list of the locations from Rome along Via Flaminia . Richard Talbert (referenced below, at pp. 271-86) reproduced the entire itinerary.

The route between Narnia and Forum Flaminii follows the eastern branch of Via Flaminia (see Richard Talbert (referenced below, at p. 285, 613:5 - 614:1)):

-

civitas Narnia - civitas Interamna (9 Roman miles)

-

-mutatio tribus tabernis (3 Roman miles)

-

-mutatio Fani Fugitivi ((10 Roman miles)

-

-civitas Spolitio (7 Roman miles)

-

-mutatio Sacraria (8 Roman miles)

-

-civitas Trevis (4 Roman miles)

-

-civitas Fulginii (5 Roman miles)

-

-civitas Foro Flamini (3 Roman miles)

This is the most detailed of the surviving itineraries: for example, it is the only one of them that mentions a number of places, including:

-

✴civitas Trevis and civitas Fulginii (modern Trevi and Foligno), between Spoletium and Forum Flaminii; and

-

✴civitas Ptanias (614:3), 20 Roman miles south of of Forum Flaminii: this centre has been identified as Tadinum, which is now an excavated area south of modern Gualdo Tadino).

However, its measures of distance are less accurate than those in the Antonine Itinerary.

Via Flaminia in Umbria

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

As noted above, we know from Livy (‘History of Rome’, 22: 11: 5-6) that, from its inception, Via Flaminia entered Umbria at Ocriculum. The surviving itineraries indicate that it continued to Narnia and then split into two branches, the west branch through Mevania and the east branch through Spoletium. These branches converged on Forum Flaminii, and the road then continued across the Scheggia Pass to Cales, on the border of the ager Gallicus.

Dates of the Respective Branches

Conventional Wisdom

Scholars generally assume, primarily on the basis of the earliest of the surviving itineraries (Strabo’s account and the itinerarium Gaditanum), that only the western branch (through Mevania) formed part of Flaminius’ project of 220 BC. Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 1997, at p. 37 et seq.) reflected this view when he described the western route as the “itinerario primitivo” and the “primitava via militare”, implying in this second phrase that its primary function was to move troops to the Adriatic coast as quickly as possible.

The relative unimportance of the eastern branch in the 1st century AD is confirmed by Tacitus’ description of one of the many atrocities carried out in 69 AD (the year of the four emperors):

-

“ [The Emperor] Vitellius summoned [his enemy Dolabella] by letter and, at the same time, gave orders [to Dolabella’s escort] that, without passing along the much frequented thoroughfare of the Via Flaminia, he should [be turned] aside to Interamna and there be put to death. This seemed too tedious to the executioner, who struck down his prisoner in a road-side tavern and cut his throat” (‘History’, 2:64).

Thus, the road from Narnia to Interamna was considered to be only a side road off Via Flaminia in 69 AD. In fact, as discussed above, the earliest direct evidence for the eastern route as a part of Via Flaminia is in the itinerarium Antoninum, which (as noted above) probably dates to ca. 300 AD.

Paolo Camerieri suggested (at pp. 64-6) that the eastern branch was unpaved until the 2nd century AD, after the further drainage of the area near Terni, perhaps in association with the viritane settlement carried out in ca. 122 BC under the auspices of Caius Semproniius Gracchus. He claimed support for this hypothesis (at p. 64) from a fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 4208) from Colle dell' Oro, Terni, not far from Via Flaminia. This inscription, which was originally picked out in bronze lettering and which is now in the Museo Comunale at Terni, reads:

[C(aius) Dexius L(uci) f(ilius)?] Ṃạx̣umus

[--- faciu?]ndam / [cur(avit?)]

In fact, there is uncertainty as to the completion of the second line of this inscription, as set out in the museum catalogue (edited by Filippo Coarelli and Simone Sisani, referenced below, at entry 102, p. 127). The authors suggested that the most likely completion recorded the archaically-named ‘Maxumus’ as the sponsor of the paving of a road or a piazza: however, while they acknowledged that the inscription had been found near Via Flaminia, they suggested that it most probably originally related to the paving of the forum of the municipium, and that it had been re-used in the location in which it was found. There is also uncertainty as to the date of the inscription:

-

✴Camerieri dated it to the 2nd century BC;

-

✴Coarelli and Sisani dated it to the middle of the 1st century BC; and

-

✴the EAGLE database (see the CIL link) dated it to the last three decades of the 1st century BC.

In short, there is no hard evidence to connect this inscription to the paving (or even the re-paving) of the eastern branch of Via Flaminia.

Thus, while it is clear that the western branch was the more important in the Augustan and early imperial periods, there is no hard evidence for the view that this had been the case since 220 BC.

Alternative Hypothesis

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 124-5) started with the observation that the earliest of the itineraries described above related to the situation some 200 years after the road’s construction. He argued (at p. 125) that:

-

“A series of indications suggest the [the route chosen by Flaminius in 220 BC] can probably be identifies as the eastern branch. The first consideration in this respect involves the link between this branch and the Latin colony at Spoletium [in 241 BC] ... it is hard to believe that this colony remained unconnected to Rome for very long, and that Flaminius had not directed his road in such a way as to bring this fortress, which had been built two decades earlier, under his control” (my translation).

To support this hypothesis, he pointed to a passage by Livy in which he described Hannibal’s actions after the fateful battle at Lake Trasimene (above), which took place very shortly after Flaminius’ road had been built:

-

“Hannibal, marching directly through Umbria, arrived at Spoletium. Having completely devastated the adjoining country, he began an assault upon the town, but was repulsed. ...[This alerted him to the problems that he would face in taking Rome. He therefore] turned aside into the territory of Picenum” (‘History of Rome’, 22:9).

Sisani argued that Hannibal’s march from Lake Trasimene to Spoletium made sense only if Spoletium had been on Via Flaminia, and was thus on the most convenient route for a rapid attack on Rome.

Sisani further supported his hypothesis for the early dating of the eastern branch by citing (at pp. 125-6) an inscription (ST UM 6, EDR 162789) that was found in 1926 at San Pietro di Flamignano (near Sant' Eraclio, some 3 km south of Santa Maria in Campis, outside Foligno), which would have been on the eastern branch of Via Flaminia:

bia . opset / marone

t . foltonio / se . ptrnio

The inscription (which is now in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci, Foligno) is in the Umbrian language and uses a cursive Latin script. The first line relates to the construction of something described as a ‘bia’, which was probably a fountain, and the rest records (probably as a dating device) two ‘marones’ (Umbrian magistrates): T(itus) Foltonius; and Se(xtus) Petronius. Giulio Giannecchini (referenced below) dated the inscription to the last decades of the 3rd century BC and (like Sisani) associated it with the opening of the eastern branch of the Via Flaminia.

Sisani observed (at p. 126) that:

-

“There is no secure chronological evidence for the opening of [the western branch], which, at least from the the end of the 1st century BC, inherited the original function of the eastern branch, eventually becoming known as Via Flaminia tout court. It must have existed [in some form] from the early phase in the Roman conquest of Umbria...: a bridge identified a little to the south of vicus Martis Tudertium ... [was probably built before] 220 BC. Furthermore, the existence of this branch is evidenced by Forum Flaminii, which must have acted from its origin as a connecting node between the two branches [of Via Flaminia]. The definitive structuring of the western route was perhaps associated with the activities of Caius Semproniius Gracchus, who was directly involved in road-building and the associated infrastructure: [another] example of this was perhaps represented by the foundation of Forum Sempronii on Via Flaminia” (my translation).

Role of Caius Semproniius Gracchus: my View

As noted above, both Paolo Camerieri and Simone Sisani suggested that the paving of the later branch of Via Flaminia (the eastern branch for Camerieri, the western branch for Sisani) took place under the auspices of Caius Semproniius Gracchus in ca. 122 BC. This suggestion is largely based on the following accounts:

-

✴According to Plutarch:

-

“[Caius] busied himself most earnestly with the construction of roads, laying stress upon utility, as well as upon that which conduced to grace and beauty. For his roads were carried straight through the country without deviation, and had pavements of quarried stone, and substructures of tight-rammed masses of sand. Depressions were filled up, all intersecting torrents or ravines were bridged over, and both sides of the roads were of equal and corresponding height, so that the work had everywhere an even and beautiful appearance. In addition to all this, he measured off every road by miles ... and planted stone pillars in the ground to mark the distances. Other stones, too, he placed at smaller intervals from one another on both sides of the road, in order that equestrians might be able to mount their horses from them and have no need of assistance” (‘Life of Caius Gracchus’, 6-7).

-

✴Appian also gave the impression that Caius Gracchus was a great builder of raods, albeit that he wrote from a more jaundiced perception:

-

“Gracchus also made long roads throughout Italy and thus put a multitude of contractors and artisans under obligations to him and made them ready to do whatever he wished” (‘Civil Wars’, 1:23).

However, Penelope Davies (referenced below, at p. 179) observed that, despite his lack of a construction mandate in his periods as tribune in 123 and 122 BC, Plutarch, in particular, credited him with extensive road-building activity. Nevertheless, she pointed out that:

-

“... no known Via Sempronia has been identified archeologically, and no surviving milestone names him; with the exception of the Via Fulvia in the Cisalpina, ... all known roads built between 133 and 109 BC were the work of his opponents or, at least, of men associated with the senatorial majority. It is possible that he reworked existing thoroughfares, replacing milestones with the names of the original constructors, or that ... [a planned project] never progressed beyond the planning stage; the Senate may even have appropriated [this putative] scheme as its own.”

Some scholars (see, for example, Oscar Mei referenced below, at p. 378) hypothesise that Forum Sempronii (modern Fossombrone) on Via Flaminia can be attributed Caius Semproniius Gracchus following the lex Semproniia of 133 BC. It rests on an inscription (CIL XI 6331) on a cippus from San Cesareo, some 22 km north of Forum Sempronii and 8km south of Fanum Fortunae, which records that, in ca. 80 BC, the future consul Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus restored the boundary stones that had been set up originally by the triumvirs Publius Licinius, Appius Claudius and Caius Gracchus. The mention of the last of these suggests that the stones would have originally marked the boundaries of land assigned to new settlers in the Gracchan distributions of ca. 130 BC. However, there is no evidence other than its name for the assertion that Forum Sempronii was founded in the Gracchan period: the archeological evidence from the site pre-dates the Augustan period.

In short, there is no hard evidence that might link Caius Semproniius Gracchus to Via Flaminia in h=general or to either branch of its branches in Umbria.

Dates of the Branches of Via Flaminia in Umbria: My view

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, p. 126) is surely correct in asserting that:

-

“... from the beginning, Forum Flaminii must have acted as a connecting node between the two branches [of Via Flaminia]” (my translation).

It appeared in all of the surviving itineraries (above) except the itinerarium Gaditanum: however:

-

✴Strabo and the Tabula Peutingeriana included it in their descriptions of the western branch; and

-

✴the Antonine Itinerary and the itinerarium Burdigalense included it in their descriptions of the eastern branch.

Both the Tabula Peutingeriana (which has it on the western branch) and the itinerarium Burdigalense (which has it on the eastern branch) locate it 12 Roman miles south of Nuceria (Nocera Umbra). In other words, it was located at precisely the point at which these branches converged. Furthermore, Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 1997) showed that the reconstruction of the routes of the two branches based on surviving archeological evidence indicates their convergence at San Giovanni Profiamma, at precisely the right distance from modern Nocera Umbra : see, for example, his descriptions of the approach to San Giovanni Profiamma:

-

✴from Bevagna on the western branch (at p. 50); and

-

✴from Sant’ Eraclio and Santa Maria in Campis (to the east of modern Foligno) on the eastern branch (at pp. 70-2).

Archeological evidence from the site itself supports this hypothesis.

We also have the evidence of surviving sources for the fact that Caius Flaminius himself founded Forum Flaminii. and that it owed its existence to the construction of his road:

-

✴Festus presented “Forum Flaminium” (and “Forum Julium”) as examples of:

-

“... fora named for the men who established them, which were used to buy and sell goods ... on roads and in fields” (‘De verborum significatu quae supersunt cum Pauli epitome’, my translation); and

-

✴Strabo (as noted above) described Forum Flaminii as one of the settlements on Via Flaminia that had been settled:

-

“... [on account of the [road] itself, rather than [as a consequence] of political organisation” (‘Geography’, 5: 2:10).

It seems to me that the most likely reason that Flaminius chose this location for Forum Flaminii was precisely because it was the point at which both branches of his original road converged.

As noted above, according to Cassius Dio, after his victory at Actium in 31 BC, when he realised that:

-

“... the roads outside the walls [of Rome] had become difficult to travel as the result of neglect, [Augustus] ordered various senators to repair the others at their own expense, and he himself looked after Via Flaminia ... ”, (‘Roman History’, 53:22).

Thus it is quite possible that both branches of Via Flaminia had been neglected during the civil wars. Perhaps Augustus’ restoration of the road privileged its western branch:

-

✴He certainly built the bridge at Narnia that took this branch of the road over the Nera: Procopius, who was writing in ca. 545 AD, recorded that it:

-

“... was built by Caesar Augustus in early times, and is a very noteworthy sight; for its arches are the highest of any known to us” (“History of the Wars”, 5:17).

-

Sadly, only one of these splendid arches still survives, but it is still known as the Ponte di Augusto. This magnificent bridge was probably built ex novo: according to Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 1997, at p. 37), there is evidence of an earlier bridge (which it presumably replaced) at the foot of the nearby modern footbridge across the river.

-

✴An important side road further along this branch of the road, after Mevania, connected it to the triumviral colony of Hispellum (Spello), which was probably reinforced after Actium: scholars often date its imposing walls and the pan-municipal sanctuary that was built in the plain below them to precisely the time of the restoration of the road. It is therefore possible that Augustus concentrated his efforts on the western branch of the road, which might account for the emphasis that the subsequent itineraries gave to it.

This might account for the fact that Strabo and other commentators in the Augustan and early imperial periods regarded the western branch as the ‘real’ Via Flaminia. If so, then the eastern branch probably served only local needs for a period, appearing in ‘international’ itineraries only after a subsequent restoration at some time before ca. 300 AD (the probable date of the itinerarium Antoninum).

Crossing the Apennines

Green = Via Flaminia, according to surviving itineraries (which post-date itsAugustan restoration in 28 BC

Red = part of the road from Rome to Sena Gallica before the building of Via Flaminia in 220 BC

Blue = assumed route of the ‘Ab Helvillo Anconam’ of the Antonine Itinerary

Underline in blue = assigned to the Oufentina tribe (dotted blue = possible assignation)

Adapted from Federico Uncini (referenced below, at p. 22)

The map above beautifully illustrates an important fact: when Flaminius planned the route of his road in 220 BC, he had the choice of a number of Apennine passes by which he could link Forum Flaminii to Ariminum. Most scholars assume that he chose the route specified, for example, in the itinerarium Burdigalense, which involves:

-

✴the Scheggia Pass between ‘Ad Heisis’ and Cales (614: 5-6); and

-

✴‘Intercisa’ (now the Gola del Furlo), between Cales and Forum Sempronii (614:6 - 615:1).

Gerhard Radke, Peter Wiseman and Ronald Syme

In a series of publications in 1959-81, Gerhard Radke suggested that Via Flaminia originally crossed the Apennines at Plestia. I have not been able to consult these publications directly, but Peter Wiseman (referenced below, at pp. 122-3) provided a summary of Radke’s basic premises. These included the assumption that each of the Roman consular roads was named for its founder and had an eponymous forum at its mid point. Thus, in the case of Via Flaminia, according to Radke:

-

✴The road built by Caius Flaminius ran through Narnia and Spoletium and on to Forum Flaminii, which was its mid point. It then crossed the pass at Plestia and followed one of the ancient ‘red routes’ on the map above to the citizen colony at Sena Gallica, before turning north along the coast to Ariminum.

-

✴In 177 BC, the consul Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus built a new road from Forum Flaminii to Ariminum, via the Gola del Furlo, as evidenced by the constitution of Forum Sempronii, again at the midpoint of the route (provided that one regarded Caesena, beyond Ariminum, as its end point, despite evidence from Livy to the contrary). By the time of the surviving itineraries, this had become the principal route.

Peter Wiseman reasonably concluded (at p. 125) that Radke’s basic premises:

-

“... are too abstract and schematic to support the superstructure of theory which he builds on them.”

He then addressed (at pp. 138-9) Radke’s specific hypothesis for Via Flaminia. In his view:

-

“The Flaminia was surely built for the transport of armies to the north ... [In this context],the main argument against [Radke’s hypothesis] is simply the route itself; from Forum Flaminii over the Plestia pass to Camerinum is a reasonable line, but from there to Sentinum it emphatically is not. Hard evidence ... would be needed to prove that any Roman road ran that way.”

However, Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 282) observed that Via Flaminia is:

-

“... one of those primordial facts of history and historical geography that seem inevitable and preordained. Yet the Flaminia [as recorded in the surviving itineraries] was neither the earliest nor the easiest line of approach [from Umbria] to the ... ager Gallicus. [Indeed,] one part of its course presents extraordinary difficulties for the passage of an army. The Pass of Scheggia [south of Cales] is both low and easy but, all the way from [this pass to the Gola del] Furlo, the road must take a course that can only be described as one long defile, for some 25 miles. Careful attention must therefore be paid to the routes leading eastwards from the line of the Flaminia before it reaches the Pass of Scheggia.”

Thus, in Syme’s view, even if Flaminius’ engineers had undertaken the considerable task of driving Via Flaminia through the Gola del Furlo, the road that resulted would have presented ‘extraordinary difficulties for the passage of an army’. By contrast, in 295 BC, as the Romans embarked on the definitive battle of the Third Samnite War, two consular armies of seem to have marched from Camerinum to Sentinum without any obvious problems.

Furthermore, there is no ‘hard evidence’ of the type that Peter Wiseman required that Via Flaminia took this difficult route in 220 BC. For example, while the two urban centres after the Gola del Furlo, Forum Sempronii and Fanum Fortunae, probably owed their existence to the northern stretch of the road, the epigraphic and archeological record at these sites does not take us back any further than the late 1st century BC, when Strabo (‘Geography’, 5: 2:10) provided the earliest surviving record for their existence. The only earlier evidence for the existence of the stretch oof road before this time is in the form of an inscription (CIL XI 6331) from San Cesareo, between Forum Sempronii and Fanum Fortunae: it indicates a Gracchan land distribution here in ca. 130 BC that might have been associated in some way with Via Flaminia.

In my view, while Radke’s basic premises are open to criticism, his hypothesis that Via Flaminia did not originally crossed the Apennines via the Gola del Furlo cannot be discounted. I address in turn below the factors that seem to me to be important in this discussion.

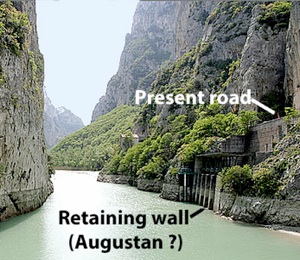

Intercisa/ Gola del Furlo

Gola del Furlo: from the website MeteoWeb

Mario Luni and his colleagues (referenced below, at p. 107) described:

-

“... the imposing works performed in order to make the [Gola del Furlo] traversable. The significant remains of the consular road and its associated structures make [it] an important and renowned archaeological site. Rock cuts and imposing walls were [initially] made on the rock spur to the [east] flank of the Candigliano river, to [make way for] and sustain the road: the amount of rock removed [in this project] is reckoned at 1,500 cubic meters.”

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2006, at p. 250) asserted that rock cutting necessary in this first phase:

-

“... extended for about 180 meters and to a height that at some points exceeded 20 meters along the side of Monte Pietralata to create an artificial terrace that was crossed by the road from its inception in 220 BC” (my translation).

He did not present his evidence for this early date. Having described this initial phase, Luni et al. (as above) continued:

-

“Later on, two tunnels were opened:

-

•a smaller one, the dating of which is uncertain (1st century BC – first half of the 1st century AD); and

-

•[a larger one cut by the Emperor Vespasian] in 76 AD, [which is still used by the present road].”

Sisani (as above) also referred to later work on this crossing:

-

“The huge wall overlooking the Candigliano adjacent to the tunnel of Vespasian was probably built in the Augustan period during the restoration of a part of the road that was evidently subsiding” (my translation).

The name Intercisa/ Ad Intercisa that the Tabula Peutingeriana and the itinerarium Burdigalense gave to the way-station on the Via Flaminia at that point would have been derived from the hewing of the rock that had been undertaken to create the second tunnel under Vespasian. It seems to me that all we can really say about the initial phase of construction is that:

-

✴it would have been a very substantial undertaking; and

-

✴it probably pre-dated the late 1st century BC, when Strabo recorded Forum Sempronii of Via Flaminia.

I wonder whether such an undertaking would have been either practical or desirable in the circumstances of 220 BC, when Rome was bracing itself for a possible invasion by Hannibal at the head of a Carthaginian army.

Sena Gallica

As note above, Gerhard Radke suggested that Via Flaminia originally reached the Adriatic coast at Sena Gallica, before turning north along it to Ariminum. It seems to me that this is at least possible: it would be odd if this road, which arguably linked the colonies of Narnia and Spoletium, then by-passed the strategically important colony at Sena Gallica.

According to Polybius, immediately after the conquest of the ager Gallicus in 283 BC:

-

“... the Romans sent the first colony that they ever planted in Gaul: namely, ... Sena [Gallica], so called from the tribe of Gauls which formerly occupied it”, (‘Histories’, 2: 19).

This colony was founded near the mouth of the Misa river in territory that must have been effectively depopulated. As discussed below, Livy described it as maritime citizen colony, which is sometimes assumed to imply that only 300 citizen settlers were enrolled here. However, as Giuseppe Lepore (referenced below, at pp pp. 231-2), observed:

-

“We can recognise [from the new archeological data] a city of dimensions quite unlike those of other maritime colonies: we are looking at [an area of some] 18 hectares, compared with 2-2.5 hectares for the older maritime colonies on the Tyrhenian coast” (my translation).

Lepore speculated (at pp. 233-4) that:

-

“Only 20 years after the foundation of Sena Gallica, the changed political and strategic situation showed how the site of Ariminum [founded as a Latin colony in 268 BC] was more suitable to serve as the headquarters for the advance to the north: obviously, the city of Sena Gallica was not abandoned, but the ‘public investment’ in it must have decreased considerably, as demonstrated by the fact that, in 220 BC, the new Via Flaminia avoided the Misa valley and instead privileged the valley of the Metaurus and the more northerly route that better connected to Ariminum” (my translation).

In fact, if one did not assume that Via Flaminia avoided Sena Gallica in 220 BC, then there would be no reason to date its decline to such an early date. Indeed, the events of 208 BC argue for its continuing strategic importance. By that time, Hannibal’s Italian campaign was running out of steam, and he was essentially confined to Bruttium and Lucania in southernmost Italy. However, Livy recorded that, when the Romans became aware that Hannibal’s brother, Hasdural, was planning to invade Italy and come to his aid. Thus, according to Livy:

-

“... everyone turned to the consuls-elect [Gaius Claudius Nero and Marcus Livius Drusus Salinator] and wished that as soon as possible they should cast lots for their provinces ... The provinces assigned to them were not locally indistinguishable, as in the preceding years, but separated by the whole length of Italy:

-

✴to [Claudius Nero] was assigned the land of the Bruttii and Lucania facing Hannibal; and

-

✴to [Livius Salinator, Cisalpine] Gaul, facing Hasdrubal, who was reported to be already nearing the Alps”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 35: 5-10).

The aim of the consuls was to prevent Hannibal and Hasdrubal from joining forces at any cost. Hasdrubal duly arrived in the Po valley and attempted the siege of Placentia. When this failed, he did not cross the Apennines but headed directly for the Adriatic. Livy recorded that:

-

“[Livius Salinator’s] camp was near Sena [Gallica], and about 500 paces away was Hasdrubal”, (‘History of Rome’, 27: 46: 4).

In other words, for whatever reason, Sena Gallica rather than Ariminum constituted the first line of the Roman’s defence. Claudius Nero assembled a detachment that he led in secret on a forced march of some 250 miles, in order to secretly reinforce the army at Sena Gallica. Hasdrubal saw through the ruse and marched north during darkness as far as the Metaurus river, before turning inland in search of a ford. However, the Roman army caught up with him before he could find a crossing. The site of the subsequent battle is uncertain, although the result is not: with his cause lost, Hasdrubal decided to die fighting, and most of his men met the same fate. This decisive Roman victory arguably marked the beginning of the end of Hannibal’s invasion.

Thus, while it is certainly possible that Sena Gallica received less ‘public investment’ than Ariminum after 268 BC, it had clearly still retained some strategic importance, at least in the period 220- 207 BC. It is difficult to know how much damage it suffered during the Battle of Metaurus, but it is perhaps significant that Livy (‘History of Rome’, 27: 38: 4) listed it among 7 maritime citizen colonies that, in 207 BC, insisted on their exemption from prolonged military duties elsewhere. It certainly seems to have been eclipsed in 184 BC, when a new citizen colony was established at Pisaurum, some 30 km to the north, and it might have been at that point that Via Flaminia was re-routed northwards.

Pass at Plestia

Green = Ancient roads; Red = Via Flaminia (220 BC) from surviving itineraries

Blue = road on Tabula Peutingeriana (ca. 300 AD)

Centres underlined = colonies; Ocriculum* and Camerinum* = allies from 308 BC

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Ronald Syme (referenced below, at 283) observed that:

-

“Roman armies marched into central and northern Umbria, even to Ariminum, long before Via Flaminia was built. It is by no means certain that they anticipated its course all the way. Indeed, this is most unlikely, given their earliest strategic objectives, [which included] Camerinum, the strong city of their trusty allies [with whom they had agreed a ‘foedus aequum’ (equal treaty) in 308 BC]. Camerinum was not merely a place on a road from Umbria to Picenum: it had a connection northwards ... [along a syncline valley that led to the territory of the Senones]. Camerinum was [for example] clearly the Roman base during the [Battle] of Sentinum.”

This is a reference to the important battle of 295 BC, when two Roman consular armies defeated the Samnites and their Gallic allies on the border between the territories of the Picenes and the Gallic Senones, in the vicinity of the later municipium of Sentinum.

In 284 BC, by which time the Roman conquest of Samnium was complete, the Gauls seem to have presented the Romans with a causus belli when, according to Polybius, they laid siege to the Etruscan city of Arretium (Arezzo):

-

“... the Romans went to the assistance of the [besieged] city and were beaten in an engagement under its walls. [Since] the praetor Lucius [Caecilius] had fallen in this battle, Manius Curius [Dentatus] was appointed in his place. The ambassadors whom he sent to the Gauls to treat for the prisoners were treacherously murdered ... At this, the Romans, in high wrath, sent an expedition against them, which was met by the tribe called the Senones. In a pitched battle, the army of the Senones was cut to pieces. The rest of the tribe was expelled from the country, into which the Romans sent the first colony that they ever planted in Gaul: namely, ... Sena [Gallica], so called from the tribe of Gauls that had formerly occupied it”, (‘Histories’, 2: 19).

Pier Luigi Dall’Aglio and Sandro De Maria (referenced below, 2010, at p. 40) observed that, given the existing road network:

-

“It is ... not surprising that:

-

•the decisive battle between the Romans and the [Samnites and their Gallic allies] ... was fought near Sentinum in 295 BC; [and]

-

•in 283 BC, immediately after the definitive defeat of the Senones, the first colony of [the ager Gallicus], i.e. Sena Gallica, was founded at the mouth of the Misa river [since the road along the Misa Valley ran in land to Sentinum]” (my translation).

Clearly the route along the Misa Valley and then the syncline valley to Camerinum would have provided a lifeline for the otherwise-isolated colonists. There is evidence that this colonial settlement was accompanied by viritane settlement on the newly-conquered territory, a development that was further stimulated by the agrarian law that was sponsored in 232 BC by none other than Caius Flaminius. We can therefore reasonably assume that these road links became increasingly important as the century progressed.