Archeological Record

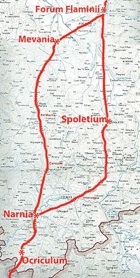

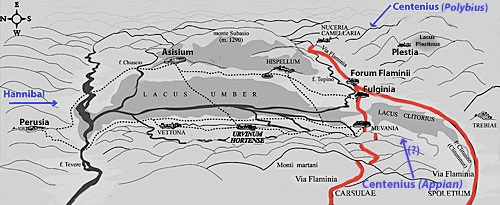

Diagram of western and eastern branches of Via Flaminia (in red),

in relation to the possible sites of Fulginia

We know that a Roman city called Fulginia existed, at least from the time of Cicero (see below). However, we know very little about its history after the Roman conquest of ca. 300 BC, a problem that is compounded by the fact that there is no secure evidence for its location.

The matter of the likely location of Roman Fulginia has been hotly debated since at least the 1930s:

-

✴Michele Faloci Pulignani (in a publication of 1936, quoted by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini, referenced below, at p. 75, note 291) observed that:

-

“The land on which our city of Foligno was built is virgin land and, however extensively it is excavated, ... important remains of ancient buildings ... are never brought to light. In contrast, every time one moves the earth near the church of Santa Maria in Campis , one finds ancient objects of all kinds ...” (my translation).

-

Thus, he believed that Roman Fulginia had been located, not on the “virgin soil” of medieval and modern Foligno, but in what is now the suburban area around Santa Maria in Campis, a kilometre from the modern city, on the eastern branch of Via Flaminia (to the lower right in the plan above).

-

✴Giovanni Dominici (referenced below), whose work was broadly contemporary with that of Michele Faloci Pulignani, reached a very different conclusion: he placed Fulginia on the site of the modern city. In particular, he argued (at p. 38) that:

-

“... the four .... bridges [over the Topino in its original course, which ran through the medieval city until its diversion northwards) cannot be later than the 1st century [BC] .... they fill a large lacuna in the history of the city: the existence of all four along a short stretch of a small river like the Topino ... proves that, from the time of the late Republic, there existed at this point a notable Roman city on the edge of a vast marshy area in the central valley of Umbria” (my translation).

-

He offered further evidence for this hypothesis (at p. 39):

-

“[A large part of] the plan of the modern city clearly reflect the traces of an ancient Roman camp: ... [all these features] combine to demonstrate this [hypothesis] in full ...” (my translation).

Modern Scholarship on the Site of Fulginia

Santa Maria in Campis

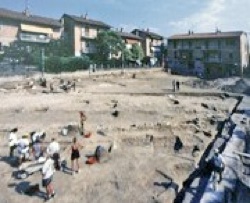

Piazza del Risorgimento, in the area of Santa Maria in Campis during excavations in 1998

(Photograph from Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci)

It is probably fair to say the the view of Michele Faloci Pulignani (above) represented the scholarly consensus for some 80 years, despite the fact that the archeological record at Santa Maria in Campis is essentially non-existent before the 1st century BC. Thus, Paul Fontaine (referenced below, 1990, at pp. 358-9) located Fulginia here, albeit with the following qualification:

-

“At the present state of research, this settlement does not seem to have developed fully until the 1st century AD. [Its] topography ... remains obscure. ... The principal axes of its roads and its forum remain to be discovered. Also, the exact boundaries of the settlement remain fluid ...” (my translation).

Other scholars commented on the lack of secure archeological evidence for the public buildings and public spaces that normally characterise Roman cities.

Reservations of this kind intensified in 1998, when 22 burials from the 1st century BC and early 1st century AD were excavated along a Roman road in Piazza del Risorgimento (at the lower right in the photograph above), at the centre of the area in which Fulginia was supposed to have existed. This has not completely undermined the hypothesis: for example, Paola Guerrini (in Guerrini and Latini, referenced below, at pp. 70-1) was of the opinion that:

-

“... the surviving Roman remains here indicate an area in which to locate the Roman city [of Fulginia], albeit with a certain margin of error regarding their [exclusively residential or funerary] nature” (my translation).

She concluded (at p. 71) that, on the basis of the totality of evidence from the area:

-

“.... it is possible to argue:

-

•[either] that the [archeological] finds to date relate to the peripheral zone [of Roman Fulginia] and its immediate suburbs;

-

•[or] that Fulginia experienced a non-concentrated pattern of urbanisation” (my translation).

Foligno

Plan of the Roman castrum proposed by Paolo Camerieri, superimposed on an aerial view of Foligno

Adapted from P. Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, p. 94, Figure 1)

I have added the locations of Roman remains (1-9) and of two possibly Roman burial sites (B1 and B2)

Giuliana Galli and Paolo Camerieri have recently revived and refined the ideas put forward by Giovanni Dominici (above) in a series of articles in two books (referenced below, 2015 and 2016). For example, Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, at p. 75) began this paper by reasserting the view that:

-

“ ... a glance at the street plan of [Foligno] or, better still, at an aerial photograph, is sufficient to arouse in any scholar of ancient urban topography the well-founded suspicion that [the hypothesis of its Roman origins] is more than likely to be correct ...” (my translation).

He identified (at p. 81) the deCumaenus maximus and cardo maximus of this putative Roman city as well as a second cardo to the northeast, which suggested the canonical plan of a Roman castrum. His observations in this respect were broadly consistent with those of Dominici, except that Camerieri reversed the identifications of the two cardines (as in the plan above).

However, as Laura Bonomi Ponzi (referenced below, at p. 12) pointed out:

-

“... the regularity of an urban plan is inconclusive proof of Roman origins if it is not supported by concrete archeological evidence” (my translation).

In other words, in order to establish the Roman origins of the modern city beyond doubt, we need evidence for buildings with Roman foundations located on its orthogonal plan. It is true that:

-

✴there are a number of Roman elements (which I have numbered 1-9 in the plan above):

-

•in and near the Duomo; and

-

•incorporated into buildings in and near Via Gramsci (along the northwestern boundary of the putative castrum); and

-

✴some of these elements suggest public rather than purely residential or funerary structures:

-

•a possible temple near the Duomo (see, for example, Giuliana Galli, referenced below, 2106, at pp. 98-107); and

-

•a possible triumphal arch, fragments of which might have been incorporated into a medieval gate at location 7 (see, for example, Fabio Pontano’s ‘Discourse’ (1618), which has been edited by Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 2008), recorded (at pp. 42-3).

Unfortunately, with the possible exception of the blocks used in a tower that was later incorporated into Palazzo Piermarini (location 3) and blocks that can be seen at pavement level in Via Pertichetti (location 5), none of the associated Roman structures survive in situ. In other words, we have little or no evidence of the kind that Laura Bonomi Ponzi (for example) deemed essential for the identification of the site of a Roman city. There is also some archeological evidence that potentially militates against this putative Roman city, in the form of a number of gabled-tile graves that were apparently found:

-

✴in front of the main facade of the Duomo (marked B1 in the street plan above) in 1900; and

-

✴in Via Cairoli (B2), part of the putative cardo maximus, in 1889.

As I understand it, gabled-tile burials are known as early as the 5th century BC and they continued in use, particularly in poorer communities, into the Middle Ages [references needed]. However, many scholars suggest that these graves in Foligno were Roman, noting that burial would not have taken place within the boundaries of a Roman city: see, for example, Bernardino Lattanzi (referenced below, at p. 72 and Figure 13) who assumed that these were Roman burials and disqualified modern Foligno as a candidate for the location of Roman Fulginia on this basis.

In other words, the evidence that survives within the boundaries of the putative Roman castrum does not take us very far in either direction (which probably explains why the debate has continued for so long). However, Giuliana Galli and Paolo Camerieri have recently added a new item to the agenda: the topographical context within which the putative Roman city at Foligno was located. I discuss this below in the light of the other evidence at our disposal relating to the history of Roman Fulginia.

Documentary Record

Unfortunately, the documentary record of Fulginia before the Social War does little to resolve the significant gaps in our understanding: as Paul Fontaine (referenced below, at p. 358) pointed out:

-

“... [Fulginia] does not appear in ancient texts before the 1st century BC” (my translation).

One author, Silius Italicus (see below), confidently recorded its existence in the late 3rd century BC but, as we shall see, little reliance can be placed on his testimony. Fortunately, Cicero also documented the city, in a speech that he delivered just after the Social War, and this provided our one reasonably secure reference to its existence in the prior period.

Silius Italicus

According to Silius Italicus, the Umbrian towns that sent soldiers to reinforce the Romans at the Battle of Cannae (216 BC) in the early stages of the Second Punic War included:

-

“... Fulginia, which stands unwalled on the open plain, ...” (‘Punica’, 8:458).

Paul Fontaine (referenced below, at pp. 359-60) observed that:

-

“We do not know whether [the statement that Fulginia was a discrete, albeit unwalled, settlement] pertained to the time of the composition of the poem (the end of the 1st century AD) or to the time of the Second Punic War” (my translation).

In fact, we might consider a more fundamental point: nothing else in the surviving literature confirms the existence at of a town called Fulginia, whether walled or unwalled, at the time of Hannibal’s invasion. While we cannot rule out the possibility that Silius had a now-lost source for Fulginia’s participation in this war, he was, as Guy Bradley (referenced below, at pp. 196-7, note 21) pointed out:

-

“... a notoriously unreliable source for this type of information.”

It is therefore more likely that he simply exercised poetic licence in respect of the unwalled city that he knew in the 1st century AD.

This hypothesis is supported (in my view) by another passage from this poem, which reports that, during the earlier battle at Lake Trasimene (217 BC), Hannibal had killed:

-

“... the luckless Varenus of Mevania, ... for whom fertile Fulginia ploughed her rich soil ...” (‘Punica’, 4:546).

As Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 276) observed, this passage demonstrates that:

-

“... Silius could come out with an authentic and impeccable Umbrian name if he wanted to: [for example, he has] a warrior who was killed at the Battle of Lake Trasimene called Varenus Mevanas, who possessed rich lands in the plain of Fulginia. The invention [of this name] avows the literary scholarship of Silius and the educated reader would take the reference to Cicero’s speech ‘pro Vareno’ [see below]” (my bold italics).

This page in the excellent website ToposText also has links to both of these references from Silius Italicus.

Cicero

The earliest surviving documentary reference to Fulginia comes in Cicero’s speech ‘pro Vareno’. Unfortunately, the speech itself no longer survives, but its substance can be at least partially reconstructed from surviving testimonies and fragments. Jane Crawford (referenced below), who has collected and commented upon the surviving information (at pp. 7-18), tentatively dated the trial to the period 77-6 BC (see p. 9). The speech was made in defence of Lucius Varenus, who was charged with the murder of two of his relatives and the attempted murder of a third. If Ronald Syme is correct in his comment on Silius Italicus (above), then this poet had learned from this speech that Varenus came from Mevania and owned land in the territory of nearby Fulginia.

We know from Quintilian that:

-

“... in the ‘pro Vareno’, [Cicero tried to divert] the charge from the accused to the slaves of Ancharius [Rufus]” (‘Institutio Oratoria’, 7:2:10).

The surviving references by Cicero to Fulginia come in two fragments of the speech that were commented on by Priscian, whose book on Latin grammar was written in ca. 500 AD:

-

“Cicero ‘pro Vareno’: «G(aius) Ancharius Rufus fuit e municipio Fulginate»:

-

idem in eadem: «in praefectura Fulginate»”

-

(‘Institutiones Grammaticae: de Nomine’ 2:348, 18-20, search on “Fulginate”);

which I translate as:

-

“Cicero, in ‘pro Vareno’: «G(aius) Ancharius Rufus was from the municipium of Fulginia; and, in the same work: «[something of relevance occurred] in the prefecture of Fulginia”.

As discussed below, many scholars suggest that Fulginia was a municipium at the time of the trial, but that some of the events that were relevant to it had taken place at a time when it had been a Roman prefecture. However, this is not necessarily correct: for example, according to Edward Bispham (referenced below, at p. 472), these fragments suggest that Fulginia was :

-

“... a municipium, but still subject to a [prefect] in the early 1st century BC.”

Pliny the Elder

Pliny the Elder (‘Natural History’, 3:19), included the Fulginates in his list of the peoples of Umbria who were assigned to the Augustan Sixth Region. We can therefore reasonably assume that Fulginia had been constituted as a municipium by ca. 7 BC, the date of Augustus’ administrative reform of Italy.

Via Flaminia (220 BC)

-

✴the eastern branch passed through Spoletium (Spoleto); and

-

✴the western branch passed through Mevania (Bevagna).

These two branches probably converged at Forum Flaminii (slightly north of modern Foligno) before continuing across the Apennines to Rimini (Ariminum) on the Adriatic coast.

There is some doubt about the precise date at which the road was built:

-

✴Festus recorded that:

-

“The Circus Flaminius and the Via Flaminia are named for the consul Flaminius, who was killed by Hannibal [in 217 BC] beside the Lake of Trasimene” (‘De verborum significatu quae supersunt cum Pauli epitome’, my translation).

-

This is sometimes taken to imply that Flaminius built the road when he was consul for the first time (i.e., in 223 BC). However, it seems more likely that Festus was simply using the consulship to identify the particular Flaminius about whom he was writing.

-

✴Livy was more specific about the date of the road: according to the Periochae (summary) of Book 20 of his ‘History of Rome’, Flaminius built it in 220 BC, when he held the post of censor.

I have followed Livy’s dating in what follows.

Dates of the Respective Branches in Umbria

The earliest surviving record of the route of Via Flaminia in Umbria was written by Strabo in 7 BC:

-

"The [Umbrian] cities ... on the Flaminian Way itself [are]:

-

✴Ocricli [Otricoli], near the Tiber;

-

✴Narnia [Narni], through which the Nar River flows ... ;

-

✴Carsuli [now the archeological site known as Carsulae]; and

-

✴Mevania [Bevagna] ... ;

-

... [together with] other settlements [on this road] that have become filled up with people on account of the Way itself rather than of political organisation; these are:

-

✴Forum Flaminium [Forum Flaminii]; and

-

✴Nuceria [Nocera Umbra] …

-

Secondly, to the right of the Way, as you travel from Ocricli to Ariminum, are:

-

✴Interamna [Terni];

-

✴Spoletium [Spoleto]; and

-

✴Aesium [Assisi] …

-

On the other side of the Way [are]:

-

✴Ameria [Amelia];

-

✴Tuder [Todi] (a well-fortified city);

-

✴Hispellum [Spello]; and

-

✴Iguvium [Gubbio], the last-named lying near the passes that lead over the mountain” (‘Geography’, 5: 2:10).

Since Strabo located:

-

✴Carsulae and Mevania “on the Flaminian Way”; and

-

✴Interamna and Spoletium “to the right of the Way”;

he clearly regarded only the western route across Umbria as part of Via Flaminia.

This was also the case for the four versions of the Itinerarium Gaditanum, (itinerary from Gades (Cadiz) to Rome) that were inscribed on the so-called Vicarello Cups at different periods around the 1st century AD: the road in Umbria ran through:

-

✴Helvillo [Fossato di Vico];

-

✴Nuceria [Nocera Umbra];

-

✴Mevania [Bevagna];

-

✴Ad Martis [outside Massa Martana];

-

✴Narnia [Narni];

-

✴Ocriclo [Otricoli]

In view of these early itineraries, scholars (see, for example, Ronald Syme, referenced below, at p. 287 and Paolo Camerieri, referenced below, 1997, at p. 37 et seq.) assume that only the western branch of the road formed part of Flaminius’ project. Paolo Camerieri suggested (at pp. 64-6) that the eastern branch was not paved until nearly a century later, after the further drainage of the area near Terni, perhaps in association with the viritane settlement carried out in ca. 122 BC under the auspices of Gaius Sempronius Gracchus

Paul Fontaine (referenced below, at p. 38) pointed out that:

-

“Although [the eastern branch] was [in his view] officially more recent, the other route [while not yet officially designated as the Via Flaminia] must certainly have been in service from the 3rd century BC in order to ensure the link with the colony of Spoletium, which was founded in 241 BC” (my translation).

Guy Bradley (referenced below, at p. 144, note 146) made the same point. Both Fontaine and Bradley clearly assumed that the account of Strabo proved that, while a road from Narnia via Spoletium to Forum Flaminii existed in 220 BC, it was not initially designated as part of Via Flaminia.

However, as Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 124-5) pointed out, Strabo’s account (our earliest surviving source) was not written until some 200 years after Flaminius’ death. He argued that:

-

✴Flaminius’ road had more probably originally followed the eastern route, through the important colony at Spoletium;

-

✴an Umbrian inscription (ST UM 6, late 3rd century BC BC) that was found at San Pietro di Flamignano, on the eastern branch of Via Flaminia (see below) was probably associated with the opening of this branch of the road; and

-

✴Hannibal had almost certainly marched along this road after his victory at Lake Trasimene in 217 BC, since his march on Rome was apparently only halted when he arrived outside the walls of Spoletium (see below).

For Sisani (at p. 126), the western branch was the later branch:

-

“... that could date back to the activities of [Gaius Sempronius Gracchus], who was directly involved in road-building. This activity ... could have been related to the foundation of [the colony of] Forum Sempronii (modern Fossombrone) on Via Flaminia [following the lex Sempronia of 133 BC]” (my translation).

My View

I find Sisani’s arguments for the hypothesis that the eastern branch of the road formed part of the Flaminius’ project persuasive, and can see no basis for the assertion of Fontaine (followed by Bradley) that, although it had existed from 241 BC, it was not formally incorporated into Flaminius’ project. However, neither can I see any basis for Sisani’s assertion that the western branch must have been a later development. In my view, in the absence of hard evidence to the contrary, we must assume that Flaminius built both branches of Via Flaminia (as evidenced by the fact that he established Forum Flaminiiat the point at which they converged before crossing the Apennines).

It is surely important to bear in mind that Strabo was writing some 20 years before the Emperor Augustus restored Via Flaminia at his own expense. It is at least possible that this branch was privileged in Augustus’ restoration:

-

✴The magnificent Ponte d' Augusto, which took the western branch of the road over the Nera, was almost certainly built as part of this project.

-

✴An important side road beyond Mevania connected Via Flaminia to Hispellum (Spello): as discussed in the following page:

-

•Augustus (while still Octavian) had established a colony here in 40 BC;

-

•he probably provided it with its impressive walls at the time of his restoration of Via Flaminia; and

-

•he probably financed the magnificent pan-municipal sanctuary below these new walls as part of the same construction project.

In other words, the western branch might have emerged as the major branch only after the restoration of 27 BC, which might well account for the way it was represented both by Strabo and the Itinerarium Gaditanum.

Later Itineraries and the Location of Fulginia

Itinerarium Antoninum

The Itinerarium Antoninum is a collection of itineraries along the roads of the Roman Empire, which includes the stopping places and the mileage between them. It was probably commissioned by the Emperor Caracalla in the early 3rd century AD, albeit that the surviving copies seem to date to the early 4th century AD. According to Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, at p. 75):

-

“... on the basis of a census of the urban centres of the Empire and the distances between them along the principal thoroughfares ....” (my translation).

Richard Talbert (referenced below, 2007, at p. 256) gave a more nuanced view:, describing a broad consensus that

-

“... it assembles individual itineraries of distinctly varied character and perhaps even date, [and that] it was compiled around 300 AD ...”

Nevertheless, Camerieri is surely correct that official information underlay the parts of the itinerary that coincide with the great consular roads, including the Via Flaminia.

The itinerary included both the western branch (reproduced in this website at location 311), under the heading ‘Flaminia’, which passed through;

-

✴Utriculi [Otricoli]

-

✴Narniae [Narni)] mpm XII

-

✴Ad Martis [outside Massa Martana] mpm XVIII

-

✴Mevaniae [Bevania] mpm XVI

-

✴Nuceriae [Nocera Umbra] mpm XVIII;

-

✴Helvillo vicus [Fossato di Vico] mpm ?

and, for the first time in our surviving sources, the entire eastern branch (reproduced in this website at location 125), which passed through:

-

✴Utriculi civitas

-

✴Narnia civitas mpm XII

-

✴Interamnia civitas [Terni] mpm VIII

-

✴Spolitio civitas [Spoleto] mpm XVIII

-

✴Foro Flamini vicus [Forum Flaminii] mpm XXVII

-

✴Helvillo vicus [Fossato di Vico] mpm XXVI

Had Fulginia been located at Santa Maria in Campis at this time, it should have appeared between Spoletium and Forum Flaminii on the eastern branch of the road. Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, at pp. 75-6) believed that its absence from this list was significant:

-

“The inadvertent omission [of Fulginia here] is somewhat unlikely ... [The more likely reason for the omission is that] Fulginia was not on Via Flaminia, near Santa Maria in Campis, but about 1 km from the road [i.e. on the later site of modern Foligno]” (my translation and my bold italics).

This observation marked the introduction to his case against Santa Maria in Campis as the location of Roman Fulginia.

Itinerarium Burdigalense

This itinerary (also known as the Itinerarium Hierosolymitanum) was written in 333 AD by a pilgrim traveling from Bordeaux to Jerusalem. The list of locations as the traveller proceeds from Rome along Via Flaminia (reproduced by the website Christusrex.org) followed only the eastern branch of Via Flaminia:

-

✴ciuitas vcriculo [Otricoli]

-

✴ciuitas narniae [Narni] milia xii

-

✴ciuitas interamna [Terni] milia viiii

-

✴mutatio tribus tabernis milia iii

-

✴mutatio fani fugitiui milia x

-

✴ciuitas spolitio [Spoleto] milia vii

-

✴mutatio sacraria [the cult site at the source of the Clitumnus)] milia viii

-

✴ciuitas treuis [Trevi] milia iiii

-

✴ciuitas fulginis [Foligno] milia v

-

✴ciuitas foro flamini [Forum Flaminii] milia iii

-

✴ciuitas noceria [Nocera Umbra] milia xii

-

✴ciuitas ptanias [Gualdo Tadino] milia viii

-

✴mansio herbelloni [Fossato di Vico] milia vii

Thus, on the face of it, the Itinerarium Burdigalense provides proof that Fulginia was on the eastern branch of Via Flaminia. However, Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, at p. 76, note 107) observed that this itinerary:

-

“... probably indicated places where one could stay securely in a city, albeit with a small deviation from the main road ...” (my translation)

My Conclusion

It is certainly true that the Itinerarium Antoninum identified only those Umbrian centres that were actually on the Via Flaminia (rather than simply close to it).

-

✴However, it did not include all such centre: for example, it omitted not only Fulginia but also two other centres in the Itinerarium Burdigalense that were certainly on (rather than simply near) the road:

-

•ciuitas treuis (Trebiae, which has been located at Pietrarossa, below modern Trevi); and

-

•ciuitas ptania (Tadinum, for which there is secure archeological evidence of its location on a surviving stretch of Via Flaminia at “Taino”, south of Gualdo Tadino, throughout the period from the 2nd century BC to the early 5th century AD.

-

✴Furthermore, with the possible exception of Fulginia, all of the urban centres listed the Itinerarium Burdigalense were on rather than near the eastern branch of the road.

Thus,while it is difficult to explain why Fulginia, Trebiae and Tadinum were omitted from the Itinerarium Antoninum, we cannot assume that the absence of Fulginia necessarily indicates that it was not located at Santa Maria in Campis.

However, neither can we assume that Fulginia must have been located at Santa Maria in Campis: the total distance from Spoletium to Forum Flaminii is:

-

✴18 Roman miles in the Itinerarium Antoninum; but

-

✴20 Roman miles in the Itinerarium Burdigalense.

The difference might, of course, simply relate to rounding errors. However, it is alternatively possible that Paolo Camerieri was correct when he suggested that the latter itinerary involved a diversion from the road to reach Fulginia.

In my view, the only hard information that we can take from these itineraries is provided by the Itinerarium Burdigalense: at least in 333 AD, Fulginia was:

-

✴about 5 Roman miles north of Trebiae and about 3 Roman miles south of Forum Flaminii; and

-

✴not more than about a Roman mile from the eastern branch of Via Flaminia.

On this basis, Fulginia could have been at Santa Maria in Campis or at Foligno, about a Roman mile to the west.

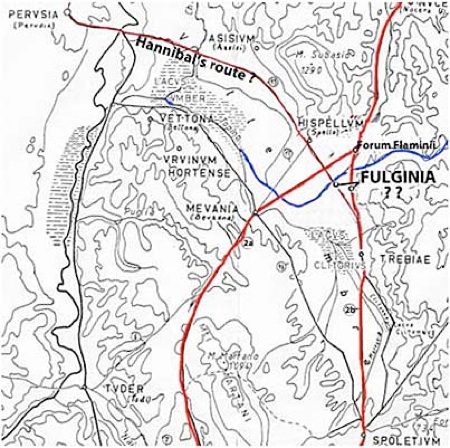

Epigraphic Record

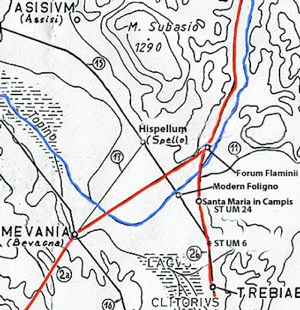

Detail from Paul Fontaine (referenced below, appended map of western Umbria)

Via Flamina in red: Fontaine designated its western and eastern branches as 2a and 2b respectively

Fontaine located Fulginia at Santa Maria in Campis, on the eastern branch of Via Flaminia,

which was the find spot of the inscription ST UM 24 (below)

I have added an alternative possibility: the site of modern Foligno, on the eastern bank of the Tinia/ Topino

* ST Um 6 = my designation of the approximate find spot of this inscription

The epigraphic corpus of Fulginia is essentially barren until the period after the Social War (90 BC), with the possible exceptions of two early inscriptions (ST UM 6 and ST UM 24, both discussed below). Thus, for example, Guy Bradley (referenced below):

-

✴included ST UM 6 and ST UM 24 under Fulginia in his list of surviving inscriptions in the Umbrian language (see his Appendix 2 at pp.281-93); but

-

✴included no inscriptions from Fulginia in his list of Latin inscriptions from Umbria that probably pre-dated the Social War (see his Appendix 3, at pp.294-300).

Marones at Fulginia ? (late 3rd century BC)

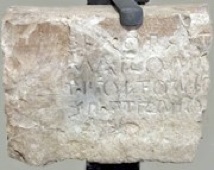

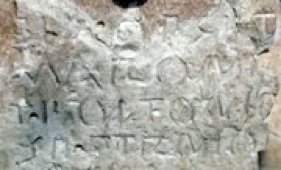

ST UM 6 Detail of ST UM 6

According to Chiara Lorenzini (referenced below, at p. 32), this inscription (ST UM 6, EDR 162789), which is now in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci, Foligno, was:

-

“... found in 1928 in a field at Colle San Pietro, between Trevi and Sant’ Eraclio, in the locality of San Pietro in Flamignano, along [the eastern branch of] Via Flaminia, about 2 km from a fountain known locally as ‘Petruio’” (my translation).

The text, which is in the Umbrian language and uses the Latin alphabet, reads:

bia . opset

marone/ t . foltonio/ se . ptrnio

The first line records the construction of something described as a ‘bia’ (probably a fountain) while the final two lines record the names of two marones (magistrates): T(itus) Foltonius; and Se(xtus) Petronius. This suggests that these ‘marones’ had commissioned the ‘bia’, although it is alternatively possible that their names were recorded merely as a dating device.

According to Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, pp. 381-2):

-

“[On the basis of paleographic analysis,] it is difficult to countenance a date later than [ca. 200 BC for this inscription]: a “terminus circa quem” [approximate date] is furnished by the opening of Via Flaminia [in 220 BC], with which the building project mentioned in the inscription could have been connected” (my translation).

Giulio Giannecchini (in L. Agostiniani et al., referenced below, at entry 33) also dated this inscription to the late 3rd century BC and associated it with the opening of the eastern branch of the Via Flaminia. Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 142) reasonably suggested that its early use of the Latin alphabet was an example of the ‘Romanising’ effect of the opening of the road.

The title of the magistracy held by Foltonius and Petronius is obviously expressed in the Umbrian language. According to Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 249), after the Roman conquest:

-

“The administrative structure of [the Umbrian communities that still enjoyed nominal independence, albeit under Roman hegemony] appears to have been based on a college formed by two pairs of magistrates: the auctores [or uhteres]; and the marones. [The auctores seem to have been] the leading magistrates within the college. ... the marones seem to have been of an inferior status, with a function associated with ... public works” ” (my translation).

If this is correct, then Foltonius and Petronius held office in a substantial urbanised community that had not yet been incorporated into the Roman state. However, as discussed in the section below on the legal status of Fulginia, other scholars believe that ‘native’ magistracies such as theirs were sometimes retained after incorporation. A more immediate concern here is whether this inscription can be securely assigned the corpus of Fulginia, and thus that Foltonius and Petronius held office there.

Guy Bradley and Simone Sisani assumed that the find spot implied that this was the case, and this is indeed the generally accepted view. However, as discussed above, there is no other surviving evidence (epigraphic, documentary or archeological) for the existence of an urban centre of Fulginia at this early date.

-

✴This does not, of course, preclude the existence of Fulginia at this time.

-

✴What it does mean is that we should at least consider the possibility that the marones of ST UM 6 held office elsewhere.

The map above identifies other possible candidates near the find spot of the inscription. We might, in my view, reasonably exclude Forum Flaminii, Trebiae and Hispellum:

-

✴Forum Flaminii and Trebiae were probably established when the road was built and are therefore unlikely to have had magistracies designated in the Umbrian language.

-

✴Hispellum is no more visible than Fulginia in the epigraphic and documentary record of this period:

-

•There is archeological evidence of its urbanisation at this early date, but Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, at pp. 47-8), for example, believed that:

-

“The few remains [of the settlement before colonisation in ca. 40 BC] are not indicative of a city; they rather indicate a vicus ...” (my translation).

-

•There is no secure surviving evidence that it was self-governing before colonisation (albeit that three inscriptions recording quattuorviri after 90 BC belong to the corpus of either Hispellum of Mevania).

Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, at pp. 47-8) believed that:

-

“... the urban settlement of Hispellum assumed the dimensions and dignity of a city only with the foundation of the colony” (my translation).

In his view, the vicus of Hispellum, like the ancient sanctuary in the plain below it, probably belonged to Mevania.

It seems to me that, while we might reasonably exclude Forum Flaminii, Trebiae and Hispellum for the reasons above, we cannot exclude the possibility that the inscription belongs to the corpus of Mevania (some 12 km from the find spot), and thus that Foltonius and Petronius held office there. I must stress that I have never seen this suggestion in the literature: as will become clear below, scholars generally assume that Fulginia existed as a substantial urban entity by 220 BC and that Foltonius and Petronius were thus marones of this city in the late 3rd century BC.

Cippus (ca. 200 BC)

The inscription, which uses the Latin alphabet, reads:

SUPUNNE / SACR

It is not clear whether the language used is Umbrian or Latin: for example:

-

✴as noted above, Guy Bradley (at p. 285) listed it as an Umbrian inscription employing the Latin alphabet; while

-

✴the Eagle database (see the CIL link) asserts that it is in Latin.

Paolo Vitelozzi (in L. Agostiniani et al., referenced below, at entry 38) dated it to the end of the 3rd or beginning of the 2nd century BC.

It is likely that the cippus marked the boundary of an area that was sacred to an otherwise unknown goddess, Supunna. Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, at p. 134) reproduced the early records of this inscription and the two main hypotheses relating to the identity of Supunna:

-

✴Alberto Calderini (referenced below, at p. 63) revived the traditional hypothesis that she was a river goddess (since ‘Supunna’ might associated with the ‘Tupino’, the Topino river of Foligno); this would be similar to the case of Clitumnus, a god associated with the nearby river of that name).

-

✴Paolo Vitelozzi (in L. Agostiniani et al., referenced below, at entry 38) referred to the hypothesis that the etymology suggested an old Latin verb ‘to throw’, which might indicate that Supanna was a goddess who presided over the preparation of food in the course of rituals of sacrifice.

This early use of the Latin alphabet, if not the Latin language, suggests the ‘Romanising’ effect of the opening of the eastern branch of Via Flaminia in 220 BC. It is difficult to extract more than this from the inscription: as Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, at p. 135) pointed out:

-

“Unfortunately, neither the archaeological context [for the discovery of the cippus] nor the exact find spot is known. We are therefore not able to say whether there was a cult building dedicated to Supunna [within the putative sacred area that the cippus indicated]” (my translation).

This putative sacred area might have belonged to Fulginia, whether that centre was located at Santa Maria in Campis or at modern Foligno. However, as noted above, we have no secure documentary of archeological evidence for the existence of Fulginia in either location at this time.

Epigraphic Record of Fulginia: My Conclusion

Both of these inscriptions were found at or close to the location of Fulginia as suggested by the Itinerarium Burdigalense (333 AD). Thus, despite the lack of evidence for the existence of Fulginia in the 3rd century BC, they probably do belong to the corpus of Fulginia. Unfortunately, neither provides hard evidence for its precise location.

Fulginia in the Second Punic War (218 - 201 BC)

Hypothetical location of the Lacus Umber [credit needed]

Via Flaminia is indicated here in red, on the assumption that both branches existed at this time

In 217 BC, Hannibal famously crossed the Alps into Italy and inflicted a series of defeats on the Romans. The most devastating of these occurred at Lake Trasimene, some 50 km northwest of modern Foligno. As mentioned above, Caius Flaminius, the builder of Via Flaminia in 220 BC and now the Roman general opposing Hannibal, was killed during this battle. As noted above, we can probably discount the claim by Silius Italicus that Fulginia was among the Umbrian towns that sent soldiers to reinforce the Romans at the Battle of Cannae (216 BC) in Apulia. However, if it existed on or near the eastern branch of Via Flaminia at this time, it is unlikely to have survived the aftermath of the Battle of Trasimene unscathed.

Hannibal in Umbria (217 BC)

Another disaster followed in the wake of the Flaminius’ defeat at Trasimene: according to Polybius:

-

“About the same time as the battle, the [other] consul Gnaeus Servilius, who had been stationed on duty at Ariminium, ... having heard that Hannibal had entered Etruria and was encamped near Flaminius, designed to join the latter with his whole army. But, finding himself hampered by the difficulty of transporting so heavy a force, he sent Gaius Centenius forward in haste with 4,000 horse [as an advance party]. But Hannibal, getting early intelligence [of this development]..., sent Maharbal with his light-armed troops and a detachment of cavalry. Maharbal ... killed nearly half [of Centenius’] men at the first encounter; and, having pursued the remainder to a certain hill, took them all prisoner on the very next day. The news of the battle of [Trasimene] was only three days' old at Rome, and the sorrow caused by it was, so to speak, at its hottest when this further disaster was announced” (‘Histories’, 3: 86).

Livy gave a similar account of this second disaster:

-

“[Soon after the defeat at Trasimene] ... another unexpected defeat was reported [at Rome]: 4,000 horse, which had been sent under the command of [Gaius] Centenius, propraetor, by the consul Cnaeus Servilius [to reinforce Flaminius] were cut off by Hannibal in Umbria, to which place, on hearing of the battle at [Trasimene], they had turned their course” (‘History of Rome’, 22:8).

Livy did not record the place from which Servilius had sent Centenius, and (unlike Polybius) he gave the victory over the latter to Hannibal himself, rather than to Maharbal. He added the important detail that Centenius’ defeat had occurred in Umbria.

Appian was more specific (although not necessarily more accurate) about these events. He had the other consul Servilius based on the Po (rather than at Ariminum) as Hannibal approached, while Centenius was living as a private citizen in Rome:

-

“The greater part [of the Roman army] was dispatched against Hannibal under [the consuls] Gnaeus Servilius and Gaius Flaminius ... Servilius hastened to the Po ... [and] Flaminius, with 30,000 foot and 3,000 horse, guarded Italy within the Apennines .... Thus had the Romans divided their large armies ... Hannibal, learning this fact, moved secretly in the early spring, devastated Etruria, and advanced toward Rome. The citizens became greatly alarmed as he drew near, for they had no force at hand fit for battle. Nevertheless, 8,000 of those who remained were brought together, over whom Centenius, one of the patricians, although a private citizen, was appointed commander ... [this force was] sent into Umbria to the Plestine marshes, to occupy the narrow passages that offered the shortest way to Rome” (‘War against Hannibal’, 9).

Appian also gave an account of the subsequent battle:

-

“When Hannibal saw the Plestine marsh and the mountain overhanging it, with Centenius between them guarding the passage, he ... sent a body of lightly armed troops under the command of Maharbal to explore the district and to pass around the mountain by night. When he judged that [these troops] had reached their destination, he attacked Centenius in front. ... The Romans, thus surrounded, took to flight, and there was a great slaughter among them: 3,000 being killed and 800 taken prisoners, while the remainder escaped only with difficulty” (‘War against Hannibal’, 11).

It is difficult to see how Appian’s account could make topographical sense, since the Lacus Plestinus (the later site of Plestia, marked at the upper right in the sketch map above) did not block Hannibal’s route from Trasimene to Rome. As Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 285) observed:

-

“.. for various reasons, it seems unlikely that the [second] catastrophe occurred precisely at the lake of Plestia: the time interval for Maharbal to get from Trasimene to Plestia and for the news to be carried to Rome will not fit Polybius’ indication... Most scholars therefore discount Plestia and put the disaster of Centenius further westwards, in the direction of Perusia.”

Ronald Syme (as above) continued:

-

“However it be [i.e. even if his account was inaccurate in important respects], Appian has preserved a valuable geographical detail. Though prone to all manner of error and confusion, he need not be accused of ‘inventing’ the lake of Plestia. The very oddity of the detail inspires a certain confidence.. How the story came to include the lake baffles conjecture. Perhaps Centenius had marched not by the Flaminia but by the Camerinum road.”

Guy Bradley (referenced below, at p. 148) also pointed out that some scholars think that Appian had confused the Lacus Plestinus with the Lacus Umber. Bradley himself was unconvinced, and Nereo Alfieri (referenced below, a paper that I have not been able to consult directly) argued that the Lacus Plestinus should be retained as the location of the battle. However, as discussed below, it does seem to me to be more likely that Centenius had occupied the passage along the shore of the Lacus Umber in an attempt to prevent Hannibal from reaching Via Flaminia. Thus, in my view, this battle might well have taken place on the north shore of the Lacus Umbra, below Asisium.

According to Livy, immediately after these victories:

-

“Hannibal, marching directly through Umbria, arrived at Spoletium. Having completely devastated the adjoining country, he began an assault upon the city but, having been repulsed with great loss and [recognising for the first time?] from the strength of this one colony ... [the difficulty of taking] Rome, he turned aside into the territory of Picenum ...” (‘History of Rome’, 22:9).

Polybius apparently had a different source for the sequence of events that followed the defeat of Centenius:

-

“Feeling now entirely confident of success, Hannibal rejected the idea of approaching Rome for the present: he traversed the country, plundering it without resistance, directing his march towards the coast of the Adriatic. Having passed through Umbria and Picenum, he came upon the coast after a ten days' march” (‘Histories’, 3: 86).

Scholars are not unanimous about the significance of these two accounts:

-

✴John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 66) observed that:

-

“Although there is no direct conflict [between them] ..., a march from Lake Trasimene to the Adriatic via Spoletium [as reported by Livy] is well nigh impossible to reconcile with Polybius’ statement that Hannibal reached the sea [in only 10 days] ...”

-

He privileged Polybius’ account, which implies a much more direct march to the coast, although he conceded that Hannibal might still have sent a raiding party to Spoletium.

-

✴However, Guy Bradley (referenced below, at p. 150) pointed out that:

-

“Polybius could be taken as referring to [a march of] ten days from the siege of Spoletium [to the coast].”

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 125) similarly accepted Livy’s account, suggesting that Hannibal had probably marched along the eastern branch of Via Flaminia in order to reach Spoletium (as noted above).

My View

Detail from Paul Fontaine (referenced below, appended map of western Umbria)

Fontaine located Fulginia at Santa Maria in Campis, on the eastern branch of Via Flaminia

I have added the alternative possibility: the site of modern Foligno, on the eastern side of the Tinia/ Topino

I have suggested the route of Hannibal’s march after Trasimene in 217 BC

After Hannibal had defeated:

-

✴Flaminius, at Lake Trasimene, some 40 km west of Perusia; and then

-

✴Centenius, probably on the northern shores of the Lacus Umber, below Asisium;

he continued either:

-

✴to Picinum and the Adriatic coast [Polybius]; or

-

✴to Spoletium [Livy].

In either event, we might reasonably assume that his route eastwards initially took him below Perusia and then along the road marked on the plan above:

-

✴Paul Fontaine (referenced below, at p. 39) described this as a Roman road that linked Perusia to Asisium, Hispellum and Spoletium, avoiding marshy areas; and

-

✴Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, at p. 85) pointed out that the present Ponte di San Giovanni dell’ Acqua in modern Foligno stands on the site of a ford in the Tinia (in its ancient course) that would have been used by travellers on this road.

From here, he could have taken:

-

✴the Apennine pass at modern Colfiorito, in order to reach the Adriatic coast; or

-

✴as Simone Sisani suggested (above), the eastern branch of Via Flaminia as far as Spoletium.

In either event, Fulginia (assuming that it existed at this point and was located at one of the two sites marked on the map) is unlikely to have escaped his attention, albeit that there is no mention of this in our surviving sources.

ANNIBAL/ CAESIS AD TRASIMENUM ROMANIS

URBEM ROMAM INFENSO AGMINE PETENS

SPOLETO/ MAGNA SUORUM CAEDE REPULSUS

INSIGNI FUGA PORTAE NOMEN FECIT

In my view, the Spoletans are surely correct: I find it impossible to believe that, while he was flushed with victory and the Romans were in disarray, he would not have pressed on immediately for Rome.

If, then, we accept Livy’s account, the Romans must have thanked their lucky stars that the walled Latin colony that had been established at Spoletium only 24 years earlier had blocked his advance. They must also have realised how vulnerable they were to future assaults along Via Flaminia, particularly along its less well defended western branch across Umbria. I suggest below that the sudden recognition of this strategic weakness might well have affected the subsequent history of Fulginia.

Tribal Allocation of Fulginia

C(aio) Anchario C(ai) f(ilio) Cor(nelia)/ Vero

dec(urioni) Fulg(iniae)

aed(ili) / F(oro)f(laminiensium)

It thus commemorates Caius Ancharius Verus, who had died while still only 22 years old. In his short life, he had served as both a decurion in Fulginia and an aedile in Forum Flaminii. Ancharius’ assignation to the Cornelia, rather than to the Oufentina, the tribe of Forum Flaminii, suggests that he came from Fulginia, which must therefore have been assigned to the Cornelia.

We might reasonably assume that Fulginia was assigned to the Cornelia when it became fully incorporated into the Roman state as a prefecture: as mentioned above, this incorporation probably pre-dated the Social War. In the section below, I discuss the main strands of modern scholarship in relation to the likely date at which this full incorporation took place.

Continue to the next page: ‘From Conquest to Municipalisation Page 2’

Read more:

A. Coles, “Between Patronage and Prejudice: Freedman Magistrates in the Late Roman

Republic and Empire”, TAPA, 147:1 (2017) 179-208

P. Camerieri, Giovanna and Giuliana Galli (Eds.), “Dal Castrum alla via Quintana, dal Tempio alla Cattedrale: Studi Topografici e Architettonici tra Ambiguità Storiche e Anomalie Urbanistiche”, (2016) Foligno

R. Syme (the author, who died in 1999) and F. Santangelo (who edited these papers from the Ronald Syme archive), “Approaching the Roman Revolution: Papers on Republican History”, (2016) Oxford

G. Galli (Ed.), “Foligno, Città Romana: Ricerche Storico, Urbanistico e Topografiche sull' Antica Città di Fulginia”, (2015) Foligno, includes:

✴G. Galli, “Foligno Città Romana: Considerazioni sugli Studi Topografici e sulle Emergenze Archeologiche”, pp. 35-74

✴P. Camerieri, “Il Castrum e la Pertica di Fulginia in Destra Tinia”, pp. 75-108

M. Laird, “Civic Monuments and the 'Augustales' in Roman Italy”, (2015 ) New York

M. Romana Picuti, “Tra Epigrafia e Antiquaria: le Iscrizioni di Supunna e delle Cultrices Collegi Fulginiae nel De Diis topicis Fulginatium di Giacomo Biancani Tazzi”, in:

E. Laureti (Ed.), “G. Biancani: De Diis Topicis Fulginatium Epistola, Foligno 1761”, (2014 ) Spello, pp. 129-43

L. Rosi Bonci and M. C. Spadoni (Eds), “Arna: Supplementa Italica 27”, (2013) Bari

P. Guerrini and F. Latini, “Foligno: Dal Municipium Romano alla Civitas Medievale: Archeologia e Storia di una Città Umbra”, (2012) Spoleto

S. Sisani, “I Rapporti tra Mevania e Hispellum nel Quadro del Paesaggio Sacro della Valle Umbra”,, in

G. Della Fina (Ed.), “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, (2012) Orvieto (pp. 409-64)

L. Agostinani et al. (Eds), “Screhto Est: Lingua e Scrittura degli Antichi Umbri”, (2011) Città di Castello

P. Erdkamp, “Soldiers, Roman Citizens, and Latin Colonists in Mid- Republican Italy”, 41 (2011) 109-46

L. Sensi (Ed.), “Discorso di Fabio Pontano sopra l’ Antichità della Città di Foligno”, (2008) Foligno

H. Mouritsen, “The Civitas Sine Suffragio: Ancient Concepts and Modern Ideology”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 56:22 (2007) 141-58

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

R. Talbert, “Author, Audience and the Roman Empire in the Antonine Itinerary”, in

R. Hensch and J. Heinrichs (Eds), “Herrschen und Verwalten: Der Alltag der römischen Administration in der Hohen Kaiserzeit”, (2007) Cologne

N. Farkas, “Leadership among the Samnites and related Oscan speaking Peoples between the 5th and the 1st Centuries BC”, (2006) PhD thesis, King’s College, London

A. Calderini, “Iscrizione Umbre”, in”

M. Matteini Chiari (Ed.), “Raccolte Comunali di Assisi: Materiali Archeologici; Iscrizioni; Sculture; Pitture; Elementi Architettonici”, (2005) Perugia, pp. 51-78

F. Coarelli, "Il Rescritto di Spello e il Santuario ‘Etnico’ degli Umbri”, in:

“Umbria Cristiana: dalla Diffusione del Culto al Culto dei Santi,” Atti del XV Congresso Internazionale di Studi sull’ Alto Medioevo, (2001) Spoleto, pp. 39-52

G. Bradley, "Ancient Umbria", (2000) Oxford

D. Gargola, “Lands, Laws, and Gods: Magistrates and Ceremony in the Regulation of Public Lands in Republican Rome”, (1999)

C. Lorenzini, “Iscrizione dei Marones da San Pietro in Flamignano”, in:

“Fulginates e Plestini: Popolazioni Antiche nel Territorio di Foligno: Mostra Archeologica”, (1999) Foligno

L. Bonomi Ponzi, “Inquadramento Storico-Topografico del Territorio di Foligno”, in:

M. Bergamini (Ed.), “Foligno: La Necropoli Romana di Santa Maria in Campis”, (1998) Perugia, pp. 11-18

P. Camerieri, “Il Tracciato della Via Flaminia”, in

I. Pineschi (Ed), “L’ Antica Via Flaminia in Umbria”, (1997) Rome

N. Alfieri, “La Battaglia del Lago Plestino", Picus, 6 (1996) 7-22

R. Feig Vishnia, “State, Society and Popular Leaders in Mid-Republican Rome 241-167 BC”, (1996) Oxford

J. Crawford, “M. Tullius Cicero: The Fragmentary Speeches. An Edition with Commentary”, (1994) Atlanta

B. Lattanzi, “Storia di Foligno: Dalle Origini al 1305”, (1994) Foligno

P. Fontaine, “Cités et Enceintes de l'Ombrie Antique” (1990) Brussels

M. Frederiksen, “Campania” (1984) London

M. Humbert, “Municipium et Civitas sine Suffragio: L' Organisation de la Conquête jusqu'à la Guerre Sociale”, Publications de l'École Française de Rome, 36 (1978)

J. F. Lazenby, “Hannibal's War. A Military History of the Second Punic War”, (1978) Warminster

W. Harris, “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

L. Ross Taylor, “The Voting Districts of the Roman Republic: The 35 Urban and Rural Tribes”, (1960) Rome

A. N. Sherwin-White, “The Roman Citizenship”, (1939, revised 1973) Oxford

H. Stuart Jones, Review of H. Rudolph (1935), below), Journal of Roman Studies, 26.2 (1936) 268-71

G. Dominici, “Fulginia: Questioni sulle Antichità di Foligno”, (1935) Verona

H. Rudolph, “Stadt und Staat im Römischen Italien: Untersuchungen Über die Entwicklung des Munizipalwesens in der Republikanischen Zeit”, (1935), Leipzig

A. Rosenberg, “Der Staat der Alten Italiker. Untersuchungen uber die Urspriingliche Verfassung der Latiner, Osker, und Etrusker” (1913) Berlin

History of Fulginia: From Conquest to Municipalisation: Page (1) Page 2

After Municipalisation Location of Roman Fulginia

Roman Walk I Roman Walk II Roman Walk III

Return to History of Foligno