Location of Roman Fulginia

Michele Faloci Pulignani (in a publication of 1936, quoted by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini, referenced below, at p. 75, note 291) observed that:

-

“The land on which our city of Foligno was built is virgin land and, however extensively it is excavated, ... important remains of ancient buildings ... are never brought to light. In contrast, every time one moves the earth near the church of Santa Maria in Campis, one finds ancient objects of all kinds ...” (my translation).

Thus, he believed that Roman Fulginia had been located, not on the “virgin soil” of medieval and modern Foligno, but in what is now the suburban area around Santa Maria in Campis, a kilometre from the modern city, on the eastern branch of Via Flaminia. I explore the surviving evidence for this hypothesis in my page Roman Walk I.

This view was challenged in the 1930s by Giovanni Dominici (referenced below), it is probably fair to say that it remains the ‘received wisdom’. However, Giuliana Galli and Paolo Camerieri (in separate articles in the books referenced below of 2015 and 2016) have recently refined Dominici’s alternative hypothesis - that Roman Fulginia was on the site of the modern city. In my page Roman Walk II, I suggest a walk around this putative Roman city to look at the surviving evidence within its boundaries.

However, as we shall see, much of the evidence for the second hypothesis is to be found outside the boundaries of this putative Roman city: it exists in the form of

-

✴the four bridges beyond its northwestern boundary that once spanned the Tinia/ Topino in its original course, to which some scholars ascribe Roman origins; and

-

✴the related matter of the location of the grave in which St Felician was buried in 250 AD, as described in his legend, BHL 2846.

These are the subject of this walk (Roman Walk III).

I attempt to evaluate the results of all three explorations in my page on the Location of Roman Fulginia.

River Tinia/ Topino

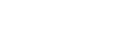

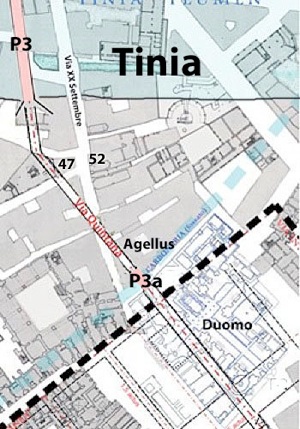

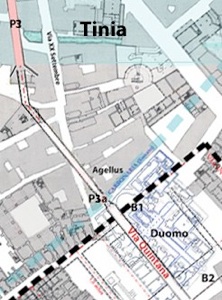

Original course of the Topino and its bridges, marked P1 - P4 (after Luigi Crema)

See the discussion below for the probable existence of bridge P2a

Northwestern boundary of putative Roman city (after Camerieri and Galli, 2016)

CM= Cardo Maximus; VQ=Via Quintana; P3a=suggested bridge over carbonaria

The Topino ran through the centre of Foligno until the early 14th century, when it was diverted to the north (and subsequently served to defend a new circuit of city walls). The original course of the river is now indicated by the residual Topinello (also known as the Canale dei Molini) and the surviving remains of the four bridges that spanned it (P1 - P4 in the plan above).

In 1930, the engineer Luigi Crema’s wrote a report on these four bridges, much of which was published by Giovanni Dominici (referenced below, at pp. 31-6). In the plan above, I have:

-

✴adapted a diagram in Crema’s report (reproduced by Giovanni Dominici, referenced below, between p. 7 and p.8); and

-

✴ superimposed on it the northern part of the street plan of Roman Fulginia, as hypothesised by Paolo Camerieri and Giuliana Galli in a number of articles in the two books (2015 and 2016) referenced below.

This shows the relationship between:

-

✴bridge P2 and the cardo maximus of this putative Roman city on the site of modern Foligno; and

-

✴bridge P3 and its Via Quintana.

If these two bridges could be be shown to be of Roman origin, this would provide considerable support for the hypothesis of Camerieri and Galli (previously put forward by Giovanni Dominici, as discussed below) that the street plan of Foligno was once the street plan of a Roman city. However, scholars are divided on the matter, and many insist that Roman Fulginia was in fact located to the east of the modern city, at Santa Maria in Campis.

Origins of the Bridges: Main Currents of Opinion

Giovanni Dominici (referenced below, at p. 31) reproduced the headline of an article in ‘La Tribuna di Roma’ following the release of Crema’s report in June 1930:

-

“Four Roman bridges have been discovered at Foligno” (my translation).

Of course, as Dominici himself had promptly pointed out to the newspaper, the bridges themselves were not newly-discovered. Rather, Luigi Crema had established for the first time that they were apparently of Roman origin. Giovanni Dominici (referenced below, at p. 37) conceded that it was difficult to establish precise dates, and noted that:

-

“Engineer Crema, in the conclusion of his report, cautiously expressed the opinion that:

-

✴the varying heights of the facing blocks;

-

✴the varying dimensions of the travertine employed; and

-

✴the slight rise of the outer curve relative to the inner one towards [the keystone ?];

-

indicate a date after the buoni tempi [heyday] of the Empire” (my translation).

In other words, in Crema’s view:

-

✴their Roman provenance was indicated by the construction techniques used; and

-

✴the late date was indicated by the departure from classical norms manifested in a degree of non-uniformity in the finished work.

Giovanni Dominici himself (at p. 38) was of a different opinion:

-

“... I firmly believe that the ... structural irregularities and inaccuracies of form that characterise the four Roman bridges of Foligno must be regarded as the result of provincialism rather than as factors that indicate a [relatively] late period for their construction. In consequence, I assert that, having regard to:

-

✴their structure of a cement conglomerate with large stone chippings;

-

✴the systematic use of travertine for the facing of their arches; and

-

✴above all, the absolute absence of the use of bricks [in their original construction];

-

the four Roman bridges of Foligno cannot be dated to a period later than the 1st century [BC]. ... they fill a large gap in the history of the city: the existence of all four along a short stretch of a small river like the Topino ... proves that, from the time of the late Republic, there existed at this point a notable Roman city on the edge of a vast marshy area in the central valley of Umbria” (my translation).

Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2015, at pp. 62-3) recently restated this position:

-

“The evidence [relating to the remains of all four bridges], still tangible and in excellent condition but very much restored ..., can be dated by comparison [with similar bridges elsewhere] and construction technique, to ... [the period from the] 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD, and [indicates] the existence [here] of a well-structured ancient urban fabric” (my translation).

However, Laura Bonomi Ponzi (referenced below, at p. 13), who located Roman Fulginia at Santa Maria in Campis, drew a very different conclusion: she asserted that Luigi Crema:

-

“... the first scholar to consider these [four bridges] in a scientific way, excluded their dating to the early imperial period, but rather [assigned them to] a later period. However, no account was taken of [Crema’s] opinion at the time of publication, which was a pity, because the misunderstandings that have dragged on for so long might have been avoided. Recent research has finally demonstrated with concrete documents that the bridges were built in the 13th century ... Of the four bridges, probably only ... [P3] can be traced back to the Roman period ...” (my translation).

This is slightly misleading: Crema considered all four bridges to be “Roman”, albeit that they were, in his view, late Roman. In addition, Bonomi Ponzi seems to have been unaware of a document from the 10th century that probably related to bridge P2 (as discussed below).

Following a detailed study of the surviving documentation (see below), Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, (at pp. 312-2, entry 98) asserted that:

-

“[P3] is the only one of the four bridges that can be dated to Roman times, albeit that it survives only in its medieval form [which they dated to the 13th century]” (my translation).

They tentatively dated bridge P2 to the 10th century (at pp. 313-4, entry 99), presumably on the basis of the document of this date mentioned above.

Documentary Record

In the footnote to the passage by Laura Bonomi Ponzi quoted above, she thanked Vladimiro Cruciani for having directed her to the chronicle of Bonaventura di Benvenuto. The relevant extracts from this chronicle (published by Guerrini and Latiini, referenced below, at pp. 252-5) are:

-

1281: “Fuerunt facte novae Carbonariae circa civitem Fulginiae”; and

-

1281: “Fuerunt facti pontes super flumen iuxta Carbonarias”

In another publication (referenced below, at p. 37), Cruciani himself asserted that:

-

“According to the chronicle of Bonaventura di Benvenuto and to the wills of [a lady called] donna Bonafemina, the bridges over the old course of the Topino were built in ca. 1280. This simple record brings into the medieval period the construction of what Dominici [above] erroneously referred to as the Roman bridges” (my translation).

However, according to Guerrini and Latini (referenced below, at p. 104), the entries in the chronicle of Bonaventura di Benvenuto:

-

“... probably refer to the two external bridges [P1 and P4], those built near the moat and thus near the [medieval city] walls ..., whose construction techniques ... have an obvious resemblance [to each other]. Since these bridges were [apparently] built only in ca. 1280, we must assume that a different system of fortification was used at the points at which the Topino entered the city under the walls of the mid-13th century” (my translation).

Bequests made by donna Bonafemina in her will of of 1277 certainly relayed to work on:

-

✴“pontis sancti Iohnnis ab aqua” [P2]; and

-

✴“pontis sancti Jacobi” [P3];

However, both featured in earlier documents, so these bequests must have related to work of restoration (as discussed below).

My Preliminary View on the Origins of these Four Bridges

The obvious point to make is that there is no scholarly consensus on the archeological significance of the surviving remains of the bridges on these four sites. Furthermore, surviving documents cannot take us back beyond the medieval period. Thus, we are reliant on circumstantial evidence in order to ascertain their likely origins.

In the case of bridges P1 and P4, I think that this takes us in the direction of medieval origins for the bridges in question:

-

✴they seem to me to have no obvious relationship to the topography of the putative Roman city on the site of modern Foligno; and

-

✴as Paula Guerrini and Francesca Latini pointed out:

-

•they were first documented only in ca. 1280; and

-

•their locations were almost certainly determined by the construction of the city walls of ca. 1240.

In contrast, bridges P2 and P3 do seem to be strongly related to the street plan of this putative Roman city. I have therefore concentrated on these two bridges in the walks below. In my view, a strong case for the Roman origins of these two bridges would also constitute a strong case for the putative Roman origins of modern Foligno.

Walk around the Bridges P2 and P3

This walk begins and ends in Piazza della Repubblica, outside the minor facade of the Duomo (at the left in this photograph), a location that is inside the putative Roman city and close to its most northerly point.

Via Aurelio Saffi, from Via Gramsci

Leave Piazza della Repubblica along Via Gramsci, with Palazzo Trinci on your right, following the northwestern boundary of the putative Roman city. Continue to the junction with Via Saffi (the putative cardo maximus) on your left. This road leads in an absolutely straight line to the junction with the putative decumanus maximus (where one would expect to find the forum).

Bridge P2

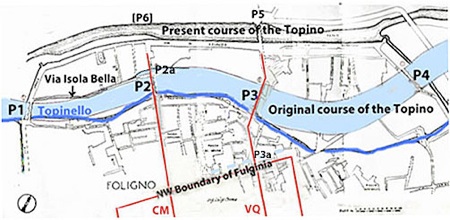

Turn left opposite the mill, through the entrance posts at number 15 (illustrated here on the left), and look back to see the underpinnings of the bridge that now takes the road over the canal (illustrated on the right):

-

✴You can see two of its arches here, protruding from under the entrance wall of the adjacent Giardino Giusti Orfini.

-

✴According to Guerrini and Latini (referenced below, at pp. 313-4, entry 99), another two arches survive under the entrance wall of this garden. (Unfortunately, it is usually closed, so I have not been able to look for them.)

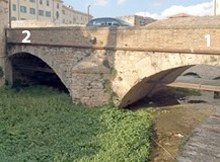

Reconstruction of bridge P2 by Luigi Crema (from G. Dominici, referenced below, p. 31)

This disposition of surviving arches of this bridge was recorded by Luigi Crema, as above: he inferred the putative fifth arch on the right on the basis of symmetry.

Isola Bella and Bridge P2a

Continue to the junction with Via Isola Bella (on the left) and Via Giovanni Pascoli (on the right). The former is named for the suburb of Isola Bella, the ‘beautiful island’: the location of this island in the river can be inferred from a surviving document from the 10th century, as discussed below.

Bridge P2, Isola Bella and Bridge P2a

According to Giovanni Dominici (referenced below, at p. 35), a notarised document of the 10th century that Michele Faloci Pulignani had shown him described a locality known as the Isola Bella as “inter duos pontes” (between two bridges). As we saw above, the name of this ‘island’ is still retained in that of Via Isola Bella. Paula Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at pp. 313-4, entry 99) observed that this document:

-

“... allows us to deduce the existence of another bridge on the northern branch of the river after it had bifurcated” (my translation).

Matelda Albanesi (in Guerrini and Latini, referenced below, Appendix II, p. 356) recorded a large semi-circular arch that had been unearthed during work at the junction of Via di San Giovanni dell’ Acqua and Via Isola Bella/ Via Giovanni Pascoli, which was further to the northeast than the arches of P2 itself. This arch was presumably the second bridge here hypothesised by Guerrini and Latini, which I have marked as P2a in the plan at the top of the page.

In 1212, Bishop Egidio gave the church of San Claudio (above) to a religious order known as the Crociferi, “cum pontem et hospitale” (together with a bridge and a hospice): the bridge in question might well have been P2a. Two bequests of donna Bonafemina (mentioned above) might be relevant to P2 and P2a respectively: they related to the financing of work on:

-

✴the “pons sancti Iohnnis ab aqua” (P2), in 1277; and

-

✴the “pons sancti Claudi” (P2a ?), in 1282.

Origins of Bridges P2 and P2a

There is no suggestion that the bridge P2a had Roman origins. However, it is interesting to note in this context that, according to Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, at p. 85), the cardo maximus of the putative Roman city:

-

“... has a probable correspondence with the ford of the river Tinia in the direction from southeast (Spoleto, Valnerina, North Sabina) to northwest (Assisi, Tiber Valley, Perugia, Central Etruria)” (my translation).

In other words, in his view, P2 had been built at a point in the river that had previously served as a ford used by travellers traversing the Valle Umbra. On this model, it is easy to imagine that, as the river bed here rose further over the centuries, a part of it became permanently exposed, creating the Isola Bella and the need for a second bridge, P2a.

There are broadly three streams of opinion regarding the origins of bridge P2:

-

✴Matelda Albanesi (in Guerrini and Latini, referenced below, Appendix II, p. 357) insisted that all four bridges had been built, ab initio, in the medieval period. In relation to this one, she argued pp. 354-6) that, although Luigi Crema had given it Roman origins, this was erroneous. She commented (at p. 355), that the only excavations carried out so far, which were associated with the laying of services along Via San Giovanni dell’ Acqua:

-

“ ... revealed the western side of the bridge as far as the third arch, which presented (like the first arch) a rib of travertine blocks ... that probably derived from a Roman monument, evidence that has sometimes given rise to the erroneous dating of the work [to the Roman period]” (my translation).

-

Her reasons for assuming that the Roman masonry in question came from another monument (rather than from an earlier Roman bridge here) were unspecified.

-

✴Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at pp. 313-4, entry 99) tentatively dated P2 to the 10th century, presumably on the basis of the document mentioned above. However, it seems to me that this document tells us only that both P2 and P2a were in existence by the 10th century.

-

✴Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2015, at p. 66) insisted that all four bridges had Roman origins. In the case of P2:

-

“[The bridge] is much restored, especially in the upper part, but the arches with large blocks of travertine and the intrados [interior curves of the arches] in blocks of marble preserve the original aspect. It is clear that the [ground below the bridge ?] has risen significantly ... and should be excavated in order to facilitate a better understanding of the dating. Very similar in its construction to [the bridge labelled P3 in the plan above], this bridge is datable on the grounds of construction technique to around the 2nd century BC” (my translation).

-

In a later paper (referenced below, 2016, at p. 116, note 295), she amended the dating of both P2 and P3 to the early 1st century BC.

The divergent streams of opinions reported above exemplify my earlier point:

-

✴there is no scholarly consensus on the archeological significance of the surviving remains of any of the bridges on these four sites; and

-

✴surviving documents cannot take us back beyond the medieval period.

Thus, we need to look for circumstantial evidence to support for any claims for Roman origins.

Adapted from Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, p. 106, Figure 14)

In the case of P2, Giuliana Galli’s view (above) is supported by an observation from her colleague, Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, at p. 92), who reported that a study of the remains of the ancient topography of modern Foligno reveals:

-

“... a very close relationship between [its street plan and the centuriated area to the west], according to a model that could be considered to be almost a textbook example [of the practices of the Roman land surveyors]. The junction of the decumanus maximus and cardo maximus [of the putative Roman city] represents, in fact, the angulus clusaris (closing angle) of this centuriated area” (my translation).

In other words, if, in Roman times, we had continued in a straight line along the putative cardo maximus and crossed a bridge that had replaced the ford at location P2, we would have then followed the northeastern boundary of the centuriated land between modern Foligno and Spello.

Camerieri argued that this topographical relationship demonstrated that this centuriated land had belonged to the putative Roman city (albeit that scholars, including Camerieri himself, had previously assigned it to Mevania). On this model, it follows that, if bridge P2 had not replaced the ford here the time of the settlement of Roman citizens that had given rise to this centuriation, then it would surely have been built soon after. Camerieri himself suggested that the centuriation had taken place place soon after the conquest in 308 BC. Other scholars suggest that veteran settlement took place at Fulginia at the time of its assignation to the Cornelia tribe:

-

✴in 220 BC, for Michel Humbert (referenced below, at p. 225), tentatively followed by Guy Bradley (referenced below, at p. 145); or alternatively

-

✴in ca. 198 BC, for Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at pp. 218-9).

The intricacies of the respective arguments need not detain us here. What is important is that, on this model, P2 was almost certainly built in the Republican period, probably on the site of a ford in the Topino that had long served travellers traversing the Valle Umbra.

My View

The marked topographical coherence between:

-

✴the long, straight road that survives today as Via Cairoli/ Via Saffi/ Via San Giovanni dell’ Acqua (which constituted the cardo maximus of the putative Roman city suggested by Camerieri and Galli);

-

✴the orientation of bridge P2, which carried this road over the Topino; and

-

✴the apparent orientation of the ancient centuriation of the land immediately to the west;

is certainly striking.

Camerieri argued that this coherence indicates that Roman Fulginia was located on the site of modern Foligno. and that this city must have owned the centuriated land to the west. This is part of the wider debate discussed elsewhere in this site. However, even if we assume that:

-

✴the present Via Cairoli/ Via Saffi/ Via San Giovanni dell’ Acqua simply reflects the street plan of medieval Foligno; and

-

✴the centuriated land to the west of P2 more probably belonged to Mevania;

it is surely still significant that the orientation of bridge P2 is coherent with the orientation of this centuriation.

In this context, it is interesting to note that, while Fulginia was assigned to the Cornelia tribe, Mevania was assigned to the Aemilia:

-

✴no other centre in the Valle Umbra was assigned to either of these tribes; and

-

✴both of these tribes were affiliated to the Cornelii Scipiones.

This led Simone Sisani, referenced below, 2007, at at pp. 218-9) to suggest that both assignations were associated with the viritane settlement of Roman veterans of Scipio Africanus at the end of the Second Punic War in 201 BC. In other words, it is at least arguable that the centuriation under discussion here probably dates to this period.

As noted above, Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, at p. 85) observed that the cardo maximus of the putative Roman city (and thus bridge P2):

-

“... has a probable correspondence with the ford of the river Tinia in the direction from southeast (Spoleto, Valnerina, North Sabina) to northwest (Assisi, Tiber Valley, Perugia, Central Etruria)” (my translation).

In other words, P2 had been built at a point in the river that had previously served as a ford used by travellers traversing the Valle Umbra, which suggests that an ancient road crossed the Topino at this point. Thus, it is at least possible that this putative ancient road determined both:

-

✴the orientation of the centuriation of the land to the west of the ford; and

-

✴the bridge that was built soon after to replace it.

In short:

-

✴while there is no scholarly consensus on the archeological significance of the surviving remains of bridge P2; and

-

✴it cannot be traced back through surviving documents beyond the 10th century;

it is at least arguable that it was built on the site of a ford in the Topino at the start of the 2nd century, when the land to the west of it was assigned for the settlement of veterans of Scipio Africanus.

Walk from P2 to P3

Retrace your steps along Via San Giovanni dell’ Acqua and turn left along Via Giovanni Pascoli. The Topinello runs parallel to this street, to your right, but the first part of it is closed to pedestrians (as at 2016), so this is as close as you can get to it. However, when Via Giovanni Pascoli turns to the left, you can turn right and walk across the car park towards it.

Bridge P3

Visible arch of P3 in Via Feliciano Scarpellini

Reconstruction of bridge P3 by Luigi Crema (from G. Dominici, referenced below, p. 31)

At 75 meters, this is the longest of the four bridges under discussion here. Look back to see the first of its seven arches (marked “1” in the photograph above). Then retrace your steps and follow Via Feliciano Scarpellini as it swings to the right across the canal: remains of the other six arches survive under the houses on your right.

According to the legend of St Felician(BHL 2846), which was probably written in the 840s, St Felician, the first bishop of Forum Flaminii, died in 250 a short distance from civitas Fulginia and was buried:

-

“... in agello ipsius ubi ipse iusserat, iuxta Fulgineam civitatem, super pontem Caesaris”.

The ‘agellus’ (small field) in which he was buried was thus located near civitas Fulginia, super (above/near/ beyond) a bridge known as the pons Caesaris (bridge of Caesar). This is the earliest surviving documentary record of a bridge of any description at Foligno.

It is usually assumed that:

-

✴St Felician’s grave was located just outside the boundary of the city of the 840s, at a point near the later site of the Duomo (as discussed below); and

-

✴the pons Caesaris of BHL 2846 spanned the Topino.

Since P3 is the nearest of the four bridges of Foligno to the Duomo, and since it was certainly known as the pons Cesaris in 1273, if not before (as discussed below), the obvious assumption is that P3 was also the pons Caesaris of BHL 2846. However, a little more analysis is needed to confirm this assumption.

Pons Cesaris in Other Surviving Medieval Documents

Location and orientation of P2 and P3, after Luigi Crema

G? = possible locations of Gragnano, as specified in 1103

A document of 1078 (reproduced by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini, referenced below, at pp. 170-1) records that Bishop Bonfiglio made a number of donations to the canons of ‘Fulginensis ecclesie’, including a mill located “iusta pontem Cesaris”. Unfortunately, this document does not record the location of this bridge (presumably because it was then common knowledge).

A document of 1103 (reproduced by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini, referenced below, at pp. 178-9) is more useful in this respect. It records a donation to the Abbazia di Sassovivo of a parcel of land that was located at a place “in comitatu Fuliensi” that was known as ‘Gragnano’ . This land was bounded by:

-

✴the side road that led from Via Flaminia to civitas Fulginia via the ‘pons Cesaris’;

-

✴a second road that led “ad wadum Bornaclum”;

-

✴a third road that led from this now-unknown location back to Via Flaminia; and

-

✴Via Flaminia itself.

This land was thus clearly on the south side of Via Flaminia, bounded on one side by the road that led from Via Flaminia to Fulginia.

-

✴We cannot now determine whether the boundary that was parallel to the latter road was to the southwest or to the northeast of this road.

-

✴However, we can be fairly sure that it crossed the Topino by a bridge known as pons Cesaris before entering civitas Fulginia.

The description in the document leaves open the question of whether this bridge was P2 or P3. Hoever, the distinctive name of the locality points strongly to P3. According to Paolo Braconi (referenced below, at p. 41), it reflected the assignation of the land in question to the gens Grania of Hispellum:

-

“In areas subject to colonial assignments, it may be assumed that the rural toponyms [such as Gragnano]... retained the names of the first holders of [the assigned] land. We can reasonably conclude from this that ... it was a Granius who received the land holding [near Fulginia] that took his name. It seems unlikely that he was a stranger to the Marcus Granius who occupied the office of duovir quinquennalis [at Hispellum in or soon after 40 BC]: indeed, it is very likely that he was the same person or, if not, then at least a member of his family” (my translation).

We might therefore assume that Gragnano was on the direct road from Hispellum to civitas Fulginia, which entered the latter city after crossing P3.

-

“...a capit pontis qui dictur pons Cesaris ...”

Since San Giacomo is located at the end of Via Feliciano Scarpellini, there can be little doubt that the pons Cesaris of 1273 was the bridge P3. This was probably the “pons sancti Jacobi” that featured in the will donna Bonafemina in 1277.

Detour to Gragnano

Make sure you look through the glass door of the church to see the important fresco (1467) by by Pierantonio Mezzastris on the altar wall before returning to the junction of Via Feliciano Scarpellini and Via XX Settembre.

Pons Caesaris of BHL 2846

If one reasonably assumes that P3 retained the same name throughout the medieval period, then bridge P3 was also the pons Caesaris of BHL 2846. Michele Faloci Pulignani (referenced below, 1934, at p. 11) was certainly of this opinion, asserting that all the surviving relevant evidence:

-

“... fits [a bridge located at P3], allowing us to assert with accuracy that this was the pons Caesaris, near which the [original grave] of St Felician was located” (my translation).

This is the generally accepted view.

However, Paolo Camerieri and Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2016, at p. 23) argued that the phrase in the legend that places this grave “super pontem Caesaris” is ambiguous.

-

✴Most scholars (see, for example, Michele Faloci Pulignani, referenced below, 1934, at pp. 10-11) translate the preposition “super”as ‘above’, but it is difficult to know what that might have signified in the late 840s: the present Via XX Settembre, between P3 and the Duomo, is quite flat.

-

✴In any case, Camerieri and Galli argued that a more precise Italian translation of the Latin “super”, when it is used in this context, is “al di là” (beyond). This suggests that St Felician’s grave was beyond (i.e. further from the city than) the bridge. If the bridge in question was P3, which is some 220 meters from the city, then the grave was slightly further away and could not have been described as iuxta (very close to) it.

They therefore concluded (at p. 24) that:

-

“We must seriously consider whether there was another watercourse, now destroyed, [that was between [the grave of St Felician and the city]” (my translation).

As discussed in more detail below, they argued that there was such a watercourse, in the form of a carbonaria (small canal or moat) that they identified in Via dell’ Oratorio (behind the apse of the present Duomo). On their model:

-

✴the pons Caesaris of BHL 2846 was a bridge across this carbonaria, immediately outside their putative Roman city, at the location marked P3a in the plan at the top of the page; and

-

✴St Felician’s grave was slightly beyond it.

I argue below that, despite the persuasive arguments put forward by these authors, I doubt that such a small bridge would ever have been known as the ‘Bridge of Caesar’. I therefore follow the traditional view that the pons Caesaris of BHL 2846 was bridge P3.

Origins of Bridge P3

There are broadly three streams of opinion regarding the origins of bridge P3:

-

✴The present consensus is probably that articulated by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at pp. 312-3, entry 98):

-

“This is the only one of the four bridges [across the Topino in its original course] that can probably be dated to Roman times, albeit that it survives only in its medieval form” (my translation).

-

This view is probably predicated on the fact the author of BHL 2846, who had more evidence at his disposal than we do, judged it to be of Roman origin.

-

✴More recently, Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2015, at p. 64), argued for the Roman origins of all four bridges. In the case of P3, she concluded that:

-

“The vaults of this bridge are realised in opera cementizia covered with pink limestone blocks, with blocks of local travertine [on the upper arch] ... on the basis of construction techniques, the date could fall between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, albeit that this awaits confirmation on the basis of surveys of the foundations of the pylons” (my translation).

-

In a later paper (referenced below, 2016, at p. 116, note 295), she amended the dating of this bridge (and the bridge P2) to the early 1st century BC.

-

✴At the other extreme, Matelda Albanesi (in Guerrini and Latini, referenced below, Appendix II, p. 357) insisted that all four bridges had been built, ab initio, in the medieval period, albeit that P3 has been:

-

“... erroneously held to be Roman on the basis of [the inscription recorded by Fabio Pontano discussed below)]” (my translation).

My View

The ‘Discourse’ (1618) of Fabio Pontano, which has recently been edited by Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 2008), includes two references to the inscription mentioned by Matelda Albanesi (above):

-

✴“In the place in Foligno called Ponte di Pietra [the later name for the Ponte di Cesare], there was a stone with an ancient inscription, which recorded that the bridge had been built when Lucius Antonius, the brother of Mark Antony, had passed with his army, which had come from Rome on the orders of Ottaviano Augusto Imperatore to besiege Perusia [in 41 BC], and this bridge was built across a stretch of marshy ground. Not long ago, this stone was removed and ... is no longer to be found ...” (my translation of a passage at p. 44).

-

✴“This ... bridge in Foligno, [now] called Pietra ... was originally called Ponte di Cesare, because it was built when the army of Ottaviano Augusto, the second Caesar, under the leadership of Lucius Antonius, passed here en route to besiege Perusia [in 41 BC]” (my translation of a passage at p. 53).

It is clear that the inscription (or the transcription of it on which Pontano relied) was inaccurate: Octavian could not have ordered the army of Lucius Antonius to build this bridge at the start of the siege of Perusia since Lucius and his army were the objects of Octavian’s siege of that city! In any case, the sheer amount of detail (inaccurate or not) that was apparently included in the inscription suggests (at least to me) that it was not nearly as ancient as Pontano believed. I think that it probably represented the elaboration of a local tradition, according to which the medieval name of the bridge reflected the fact that it had been built by the Emperor Augustus. This putative local tradition was not necessarily inaccurate: the medieval name could have commemorated Augustus himself or his deified ‘father’, Julius Caesar. However, this name alone hardly constitutes proof that the bridge had been built by either Augustus or any other Roman “Caesar”.

Having said that, the fact that Fulginia was involved in the Perusine War might be of relevance to this discussion. Octavian’s general, Agrippa, blockaded Ventidius, an ally of Lucius Antonius, here in 40 BC, thereby preventing him from helping Lucius Antonius to break out of Perusia: this blockade might well have involved the destruction of any bridges that spanned this stretch of the Topino. The horrors of the Perusine War represented the culmination of the disasters inflicted on the Valle Umbra throughout the civil wars that marked the end of the Republic. When Octavian returned his attention to the region after his final victory at Actium, he did so as the Emperor Augustus:

-

✴ the bringer of peace and prosperity;

-

✴the restorer of the Via Flaminia (in 27 BC); and

-

✴the builder of the magnificent pan-municipal sanctuary below Hispellum (probably at about the same time).

It is thus at least possible that he also built new bridges on the Topino, including the pons Caesaris and that this fact was indeed reflected in its medieval name.

Location and orientation of P2 and P3, after Luigi Crema

G? = possible locations of Gragnano, as specified in 1103

To push this idea forward, it is necessary to consider it in a wider context. I argued above that it is at least possible that the bridge P2 had its origins in the republican period, when it replaced a ford in the river that had previously been used by people traversing the Valle Umbra. However, it seems to me that there would have been no need for a second bridge P3 at this early date:

-

✴P3 stands at the widest point in this stretch of the river, which is not an obvious place at which to build a bridge unless there was a specific need for it; and

-

✴in fact, there was no obvious need for it:

-

•the road across it would have met the Via Flaminia at a point that was only about 1 km from the point at which it was crossed by the road from P2; and

-

•although it would have offered a direct rout to to Hispellum, this was then only a relatively insignificant urban centre.

I also argued that any bridges on this stretch of river would have probably been destroyed by Agrippa in 40 BC. We can reasonably assume that P2 was subsequently rebuilt in order to restore the line of communication through the Valle Umbra. The likelihood is that its rebuilding coincided with the restoration of Via Flaminia by Octavian - now the Emperor Augustus - in 27 BC.

I think that bridge P3 might also have been built at this time, because the road across it would now lead to the important colony of Hispellum:

-

✴this colony, which had been established in ca. 40 BC, had probably received a second waive of veterans after Actium;

-

✴it had also received an impressive circuit of walls in ca. 27 BC, an undertaking that had no purpose other than to demonstrate its new prestige; and

-

✴new territory assigned to it at this point probably included a corridor of land along this branch of the Via Flaminia:

-

•the gens Grania of Hispellum apparently owned land at Gragnano, as discussed above; and

-

•Cnaeus Decimus Bibulus, a veteran who had been settled at Hispellum after Actium, was buried at Fiamenga, the find spot of his epitaph (CIL XI 5275), some 4 km further along Via Flaminia, towards Mevania,.

-

This might well explain why, in the so-called Rescript of Constantine (CIL XI 5265, ca. 335 AD), the Emperor Constantine referred to:

-

“... your city, which is now called Hispellum and which you report borders immediately on Via Flaminia ...” (from the translation by Noel Lenski, referenced below, at pp. 118-9).

Even more importantly, a magnificent pan-municipal sanctuary now stood in the plain below Hispellum (on the site of the present Villa Fidelia) and was almost certainly intended as the place at which the people of the Valle Umbra could assemble to celebrate the peace and prosperity of the new Augustan age and to honour the bringer of these benefits.

On this model (which I find persuasive), the building of the pons Caesaris would have facilitated the construction of a new ceremonial route (perhaps a via triumphalis) from Fulginia to this pan-municipal sanctuary.

P3 and Via della Quintana of the putative Roman city

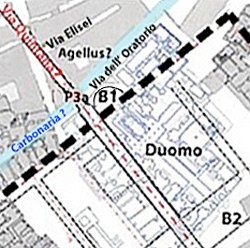

Adapted from Camerieri and Galli (2016, p. 29, Figure 3)

P3 = my pons Caesaris but the authors’ Ponte Pietra; P3a = authors Ponte Cesare

Medieval Porta Strettura (discussed below) was between 47 and 52 Via XX Settembre

That brings us back to the question of the location of Roman Fulginia. In principal, this bridge could have served this ceremonial purpose for a city located anywhere within a reasonable distance of the south bank of the Tinia/ Topino. However, Paolo Camerieri and Giuliana Galli surely make a powerful point in the diagram reproduced above: this bridge would have been coherently located in relation to the second cardo (Via Quintana) of their putative Roman city on the site of modern Foligno.

Walk from Bridge P3 to Bridge P3a

View of Via XX Settembre from the north

The Duomo is ahead and bridge P3 is to the right

Look along Via XX Settembre, towards the Duomo. According to Vladimiro Cruciani (referenced below, at p. 29), two stretches of the first circuit of city walls here were subsequently incorporated into the buildings:

-

“...at numbers 52 and 47 [marked on the photograph and the plan above], adjacent to Porta Strettura, [which] had large Roman blocks reused in its base (like almost all of the towers of the city) ...’ (my translation).

According to Vladimiro Cruciani, this gate was demolished in 1880, when Via XX Settembre was widened in order to improve the access to Piazza San Giacomo. However, Ludovico Jacobilli (quoted by Guerrini and Latini at p. 316, entry 105), who was writing in the 17th century, recorded that it had been built:

-

“... of ancient stones, with a tower above, at the end of the street named Strettura, ... not far from the Ponte di Cesare, now called Ponte della Pietra ...” (my translation).

An Augusta Arch?

I wonder whether the ancient stones in the base of Porta Strettura had originated in a Roman arch located located just before the bridge P3:

-

✴I speculated above that the Emperor Augustus might have built the bridge P3 as part of a ceremonial route to the new pan-municipal sanctuary at Hispellum.

-

✴An Augustan triumphal arch here, which might have commemorated Augustus’ triple triumph of 29 BC, would have been a fitting point of departure for people using this route to attend imperial celebrations at this sanctuary.

However, this can only be a matter of speculation.

Epitaph of Tutilia Laudica

D(is) M(anibus)/ Tutiliae/ Laudicae

cultrices/ collegi(i)/ Fulginiae

Thus, the ‘cultrices’ (worshippers) of the (presumably pagan) college of Fulginia commemorated Tutilia Laudica, who had probably been among their members.

Agellus of St Felician

Proposed location of the agellus of St Felician in relation to the putative Roman city at modern Foligno

Adapted from Camerieri and Galli (2016, p. 29, Figure 3)

B1 and B2: burial grounds identified by Michele Faloci Pulignani (my additions to the plan)

Continue along Via XX Settembre to the junction with Via dell’ Oratorio on the left, which runs behind the apse of the present Duomo. This is a good place to consider the location of the agellus of St Felician (i.e. the small field in which he was buried in 250 AD), which was located (according to BHL 2846):

-

“... iuxta Fulgineam civitatem, super pontem Caesaris.”

Location Proposed by Michele Faloci Pulignani

According to Michele Faloci Pulignani (referenced below, 1934, at pp. 9-10):

-

✴A document in the the archives of the Cathedral Chapter records that,when the old apse of the Duomo (at B1 in the plan above) was demolished in 1457, it was discovered that:

-

“... nel sottosuolo erano sepolti dei cadaveri.”

-

Faloci Pulignani specified neither the number of these bodies nor the nature of their graves.

-

✴A document in the archives of the Abbazia di Sassovivo records that, when the area in front of the main facade of the Duomo (at B2 in the plan above) was excavated in 1900, this whole area was found to be occupied by graves covered by large gabled tiles.

Michele Faloci Pulignani inferred from these documents (at p. 9) that a cemetery must have surrounded the Duomo and concluded (at p. 10) that:

-

“The land that had belonged to St Felician, on which he was buried, subsequently became the site of the Duomo and the adjacent structures” (my translation).

Faloci Pulignani had thus assumed that at least some of the burials at B1 and B2 were Roman burials: this model presented no difficulties in relation to Roman legislation that banned burial inside city walls since he believed that Roman Fulginia was near Santa Maria in Campis.

Location Proposed by Paolo Camerieri and Giuliana Galli

According to Paolo Camerieri and Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2016, at pp. 18-9), for whom the Roman city was on the site of modern Foligno, the likelihood was that St Felician would have been buried beside one of the main roads that led out of the city.

-

✴the indication iuxta Fulgineam civitatem suggested a location very close to it; and

-

✴for reasons that these authors set out at p. 23, the phrase super pontem Caesar indicated a location beyond and/or to the north of this bridge (which they identified as the bridge P3a, as discussed further below).

They therefore suggested the location for the agellus as in their Figure 3 above, beside the putative Via Quintana.

Documentary Evidence for the Agellus

Three documents published by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, in the tables at pp. 168-261) throw some light on the location of the agellus:

-

✴In 1078, Bishop Bonfiglio made a number of donations to the canons of the ‘Fulginensis ecclesie’, which included land “in Agello”.

-

✴In 1082, a donation to the Abbazia di Sassovivo included land “in locum qui dictur Agellum, ubi prope est aedificato ecclesia et civitas Sancti Feliciano”. The preposition prope means ‘near’, so the locality then called Agellum was outside the city but nonetheless close to both the city and the Duomo (which was obviously within it).

-

✴In 1147, a document recorded the sale of a property in locum qui dictur Agellum that was bounded on one side by a carbonaria (a canal, which was presumably fed by the Topino).

We might reasonably assume that the expressions “in Agello” in the earliest of these documents and “in locum qui dictur Agellum” in the other two all relate to the same locality, and that this locality was named for the agellus of St Felician, which was presumably located within it.

My View

For Michele Faloci Pulignani, St Felician was buried in a Roman cemetery that existed under the present Duomo. Although this church probably did not exist in the 840s, we can reasonably assume that it stands on or near the site of the episcopal church of that period. This church was surely within the city boundary, whereas BHL 2846 tells us that St Felician was buried near (i.e. not inside) it. In other words, even if Faloci Pulignani was right to assume that the Duomo stands on the site of a Roman cemetery, BHL 2846 indicates that St Felician was not buried in this cemetery.

On the other hand, if one reasonably assumes that the carbonaria identified by Camerieri and Galli marked the boundary of medieval civitas Fulginia, then their proposed location for the agellus is exactly where the document of 1082 says it was: outside civitas Fulginia but nonetheless close to the Duomo.

In my view, therefore, the site proposed by Camerieri and Galli is probably the correct one. On this model, the agellus might well have been located within an extra-urban area used for burials, which extended from site B1 towards the present Via Elisei.

Carbonaria and Bridge P3a

Carbonaria

Entrance to Via dell’ Oratorio from Via XX Settembre

I am grateful to Paolo Camerieri for pointing out to me what seem to have been

openings for the supports of a mill wheel in the walls here

Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2016, at pp. 55-6) assembled the archeological evidence for a carbonaria (canal) that ran under Via dell’ Oratorio. He also identified the signs of a water mill at the entrance to Via dell’ Oratorio from Via XX Settembre (picked out in white in my photograph above), which he illustrated in his Figure 14. He referred in this context to a document of 1078 (reproduced by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini, referenced below, at pp. 170-1) that records that Bishop Bonfiglio made a number of donations to the canons of the ‘Fulginensis ecclesie’, including two mills:

-

✴one located “iusta pontem Cesaris”, as mentioned above; and

-

✴the second “in castro eiusdem ecclesie”.

Although the evidence for this stretch of the carbonaria seems to relate to the medieval period, Camerieri hypothesised (at p. 55) that it had previously defended the northwestern boundary of the putative Roman city on the site of modern Foligno.

Site B1 (again)

Take a short detour by walking a little way along Via dell’ Oratorio to see the apse of the Duomo, on the right (at site B1 in the plan above). As noted above, a number of burials were discovered when the original apse here was demolished in 1457:

-

✴Michele Faloci Pulignani suggested that this area formed part of a cemetery that surrounded the Duomo and that the agellus of St Felician had been located within it.

-

✴Paolo Camerieri and Giuliana Galli suggested that these burials were located between the carbonaria in Via dell’ Oratorio and the northwestern boundary of the putative Roman city, while the agellus of St Felician was on the other side of this carbonaria.

As noted above, I think that the latter suggestion is the more likely.

Bridge P3a

Bridges P3 and P3a, following Camerieri and Galli (2016, p. 29, Figure 3)

P3: the authors’ Ponte Pietra; P3a: their Ponte Cesare

As noted above, the legend of St Felician (BHL 2846) located the agellus (grave) of St Felician “super pontem Caesaris”. I discussed above the scholarly consensus that this bridge spanned the Topino at location P3.

However, Paolo Camerieri and Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2016, at p. 23) argued that a more precise Italian translation of the Latin “super”, when it is used in this context, is “al di là” (beyond and/or to the north). Thus, although the agellus was iuxta (near) the city, the bridge was nearer still. They therefore concluded (at p. 24) that:

-

“We must seriously consider whether there was another watercourse, now destroyed, [that was between the agellus and the city]” (my translation).

Their answer was the carbonaria under Via dell’ Oratorio.

This left open the location of the bridge, but the answer was relatively obvious: as they pointed out (at pp. 24-5), their putative Via Quintana would have crossed the carbonaria via the bridge that I have labelled P3a. Thus, in their Figure 3 (at p. 29):

-

✴bridge P3 was labelled “Ponte Pietra”; and

-

✴the “Ponte Cesare” of BHL 2846 was bridge P3a.

My View

Reconstruction of bridge P3 by Luigi Crema (from G. Dominici, referenced below, p. 31)

Paolo Camerieri suggested (at p. 25) that:

-

“... the suspicion that there could have been two bridges in this area rather than just one had already been signalled by the traditional double denomination that seemed to refer to both the Ponte di Cesare and the Ponte Pietra within the same narrative context” (my translation).

He gave a specific example (at note 48):

-

“The marchese Balduino Barnabò, on page 1 of his notes of excavations of the Duomo [in 1824], ... states that the Ponte di Cesare started at the so-called Ponte della Pietra and ended at the start of the Piazza di San Giacomo with three arches under which the Topino had passed in ancient times” (my translation).

However, it seems to me that Barnabò simply meant that the Ponte della Pietra was the name given in his day to the visible part of P3 (arch 1 in the plan and photograph above) and that he was aware of another three of the arches of this ancient bridge, properly called the Ponte di Cesare, that survived under the buildings closer to Piazza San Giacomo (arches 5-7). In other words, I doubt that he was making any reference to a bridge at P3a.

More generally, I think that the mutability of the name used for P3 over the centuries is less pronounced than Camerieri suggests.

-

✴For example, both Fabio Pontano and Ludovico Jacobilli recorded that P3 was usually known as the Ponte di Pietra by the 17th century, although they were both aware of its ancient name:

-

•Fabio Pontano, in his ‘Discourse’ (1618), recently edited by Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 2008), recoded that the:

-

“... bridge in Foligno, [now] called Pietra ... was originally called Ponte di Cesare ...” (my translation of a passage at p. 53); and

-

•writing in 1646, Ludovico Jacobilli, quoted by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 316, entry 105), recorded that a city gate called Porta Strettura was built:

-

“... not far from the Ponte di Cesare, now called Ponte della Pietra ...”.

-

✴The situation in the medieval period is more confusing:

-

•Giovanni Dominici (referenced below, at p. 34) asserted that P3 appeared in medieval documents (in the plural) as the pons Lapideus, but gave no references.

-

•Bernardino Lattanzi (referenced below, at p. 93), citing a paper by Michele Faloci Pulignani, (“‘Fragmenta”, Biblioteca Comunale, Foligno, p. 12), asserted that it was:

-

“... [alternatively] known from 1078 as: pons Cesaris; or pons Lapideus; or pons S. Jacobi ab Aqua” (my translation).

-

•I have yet to find Faloci Pulignani’s paper, but it seems to have been influential: Paolo Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 312, entry 98) reproduced this assertion, citing Lattanzi.

-

However, Faloci Pulignani himself (referenced below, 1934, at pp. 10-1) made no mention of any medieval reference to a pons Lapideus: in his consideration of the pons Caesaris of BHL 2846, he described only the documents of 1078 and 1103 that refer to the bridge using this name and concluded that:

-

“All these circumstances are so well adapted to the present Ponte della Pietra to make it absolutely clear that this is that pons Cesaris, near which was located the agellus of St Felician” (my translation).

-

All this makes me wonder whether there is a secure basis for the assertion that P3 was sometimes referred to as the pons Lapideus in medieval documents.

My conclusion is that P3 was generally known as the Ponte di Cesare in the medieval period and as the Ponte Pietra thereafter: the change might well have arisen after the river had been diverted and most of P3 had been built over, leaving only a single arch known as the Ponte Pietra across the the Topinello.

Although the archeological evidence assembled by Paolo Camerieri (above) indicates the likely existence of P3a across a carbonaria here, , at least in the medieval period, there is no surviving documentary record of it an thus no basis on which to speculate about its name. However, I have to say that I find it hard to believe that this small bridge ever had the grand name of pons Caesaris or Ponte Cesare.

In short , despite the persuasive nature of the linguistic arguments put forward by Camerieri and Galli (above), I prefer to follow the established tradition that the pons Caesaris of BHL 2846 was bridge P3, and that it retained this name throughout the medieval period:

-

✴I agree with Camerieri and Galli that the agellus of St Felician was probably to the left of what is now Via XX Settembre as it approaches the Duomo.

-

✴Perhaps this site was indeed perceptibly “above” the Topino and its bridges in the 840s ?