Introduction

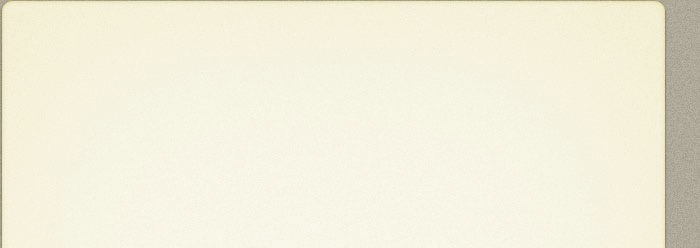

Map of Mesopotamia, showing the extent of the Akkadian and ‘Ur III[ Empires

Image adapted from Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2021, Map 2.1, at p. 69)

My additions: text in red and blue

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2021, at p. 44) observed, as far as we know:

-

“... the two earliest examples of imperial experiments on record [are]:

-

✴the empire of Sargon of Akkad (2300-2200 BC); and

-

✴the [empire of the so-called Ur III dynasty] (2100-2000 BC).”

However, Sargon’s ‘imperial experiment’ must have been conditioned by political developments in the surrounding region and, as Steinkeller suggested (at p. 44), a:

-

“... direct antecedent of the Sargonic Empire, in both time and space, was [probably] the kingdom of Kish ...”

He acknowledged that:

-

“... due to the scarcity of relevant historical data, this Kishite entity remains largely a hypothetical construct ...”

However, he referenced a number of his earlier papers in which he hypothesised that Kish had exercised hegemony over large areas of northern Mesopotamia and the Diyala region to the east. I will discuss this difficult body of evidence below.

First, however, we might usefully digress to look at the so-called ‘Sumerian King List’, a somewhat problematic ‘document’ that suggests that the early ‘Ur III’ rulers saw themselves as the heirs of both Sargon and the kings who had ruled at Kish before it became part of Sargon’s empire.

Sumerian King List (SKL)

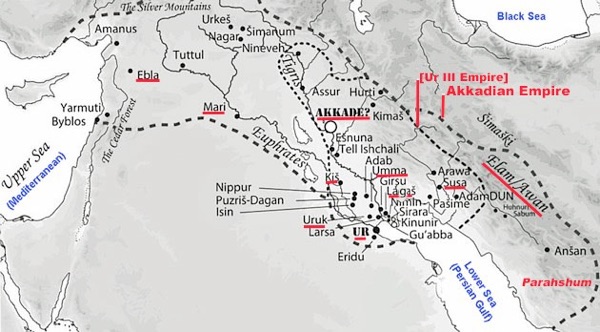

Old Babylonian Recension of the Sumerian King List (SKL) on the so-called Weld-Blundell (WB) Prism

Now in the Ashmolean Museum: image from the museum website

Gianni Marchesi (referenced below, 2010, at pp. 232) characterised the SKL as:

-

“... a composition halfway between a literary text and a list proper, which deals with the history of kingship in [Sumer = southern Mesopotamia] from the beginning of time to the early centuries of the 2nd millennium BC. ... In this narrative framework, all the rulers who allegedly held sovereignty over the whole of [Sumer] are listed one after the other. ... Apart from a single] break at a time of political confusion and anarchy (during which it was not clear who the king was), ... the SKL provides us with an unbroken sequence of kings who [allegedly] exercised kingship [in Sumer].”

As will become clear, the surviving evidence makes clear the fact that no single individual (from Kish or from anywhere else) exercised effective and continuing hegemony over the totality of the Sumerian city states before Sargon. However, as we shall see, a detailed examination of the SKL offers an interesting perspective on the elusive ‘kingship of Kish’

Discovery of the SKL

The ‘discovery’ of the SKL began with the Weld-Blundell (WB) Prism (illustrated above), which contains a Sumerian cuneiform text (transliterated as CDLI, P384786) from the so-called Old Babylonian period (ca. 2000-1600 BC). The provenance of the prism is unknown:

-

✴it was first recorded as part of the private collection of Herbert Weld-Blundell, who presented it to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford in 1923; and

-

✴Stephen Langdon (referenced below) published it (as WB 444) shortly thereafter.

Fragments of similar texts had been known some years earlier, but the connections between them only became apparent after the publication of the essentially complete WB 444. When Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below) published the first critical edition of the SKL in 1939, he was able to rely on WB 444 and 14 other (less complete) texts (which he listed at pp. 5-13). In 2004, Jean-Jacques Glassner (referenced below, at pp. 118-25) published an updated version of WB 444 (his ‘manuscript G’, see p. 117), which he entitled ‘Chronicle of the Single Monarchy’ (the ‘single monarchy’ in question being that of Sumer). Since then, the SKL corpus has expanded from 14 to 26 recensions, and these are the subject of a critical edition that Gösta Gabriel is about to publish: I would like to express my gratitude to Dr Gabriel for allowing me to read a pre-publication copy of this important (and much-needed) book.

As Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 235) pointed out:

-

✴24 of the 26 manuscripts in the modern corpus (including WB 444) date to the Old Babylonian period: and

-

✴there are two ‘chronological outliers’:

-

•the oldest known copy of the SKL was compiled in so-called Ur III period (ca. 2100–2000 BC), for which reason it is usually referred to as the USKL; and

-

•a single later manuscript probably dates to ca. 1600–1450 BC.

For our present purpose, we should concentrate on the USKL, since all of the later versions represent elaborations of this text.

USKL Recension

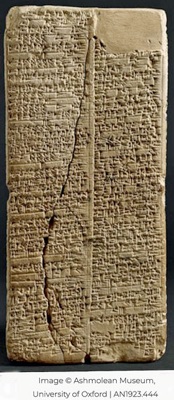

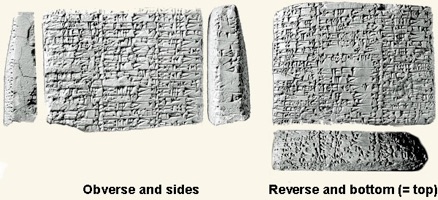

Surviving part of the tablet containing the Ur III recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL):

the tablet is in a private collection and the image adapted from CDLI: P283804

In 2003, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below) published what was (and is still) the earliest known version of the SKL, which is on a clay tablet that was (and is still is) in a private collection: he provided a transliteration of and an important initial commentary on the text, and a transliteration and photographs are also available on line at CDLI: P283804. In what follows, references to specific lines in these texts adopt the numbering system used by the CDLI.

Since the final lines of the text are complete, we know that the scribe dedicated his handiwork to:

-

“... [the divine] Shulgi, my king: may he live until distant days (see, for example, the translation by Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 269).

As he pointed out:

-

“... by all indications, Shulgi was still alive when [this text] was written down, as the invocation suggests.”

He also argued (at p. 269) that, since Shulgi was given a divine determinative in this dedication, it must have been compiled at some time between:

-

✴his 20th regnal year (the approximate date of his deification); and

-

✴his 48th regnal year (the approximate date of his death).

We can thus date this recension of the SKL to the reign of Shulgi, the son and successor of Ur-Namma, who was the founder of what we know as the Ur III dynasty and the last-named king in this recension (hereafter the USKL).

Even more fortunately, since the opening lines of the text are also complete, we know that it started with the rather startling assertion that:

-

“After nam-lugal (kingship) came down from heaven, kisheki lugal-am3 (Kish was king). In Kish, Gushur reigned for 2,160 years”, (see, for example, the translation by Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, 2010, at p. 231).

Steinkeller also established (at p. 274) that:

-

✴Gusher was followed by about 30 more Kishite kings (although only 22 names, including that of Gusher, survive); and

-

✴these Kishite kings would have represented about 40% of all the kings named between Gusher and Ur-Namma.

He argued (at p. 282) that neither Shulgi and Ur-Namma at Ur nor their immediate predecessor, Utu-hegal at Uruk, would have:

-

“... had any part in a project that assigns much of the past glory to Kish, ... This leaves us with only one possible agency [for the list of Kishite kings in the USKL: Sargon [of Akkad and his successors, who would] have had an obvious interest in promoting the idea that Kish remained the seat of kingship from time immemorial down to Sargon’s own day. In such a scheme of history, Akkad became a natural heir and successor to Kish …”

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023at p. 244) further argued that Sargon and his ‘Akkadian’ successors would have relied for most of their king list on the Kishites’ own historiographical tradition, in which case:

-

“... the first recension of what would become the [USKL and subsequently the SKL would have been] written in Kish before ca. 2350 BC.”

If so, then Shulgi’s scribe would have relied heavily on this putative ‘Kishite recension’ (as mediated by the Akkadian conquerors) for the early part of the USKL.

In this scenario, Sargon or one of his successors sought to establish the legitimacy of the Akkadian rule of Kish by (inter alia) adding the names of the successive kings of his own dynasty to the ‘official’ list of kings of Kish, presumably with a short narrative that set out the circumstances in which this kingship had passed to Sargon (who was already the king of Akkad). Unfortunately, the USKL is of no help in establishing the likely content of this narrative, since the ca. 30 lines of text between the records of Meshnune (the last name in the surviving Kishite list) and Sargon of Akkad have been lost. However, it is clear that:

-

✴the Akkadian kings derived considerable advantage by associating themselves with what must have been a well-established tradition in which the kingship of Kish had been in the gift of the gods since time immemorial; and

-

✴(pace Piotr Steinkeller, above) Shulgi derived considerable advantage by portraying his father, Ur-Namma, as the legitimate heir of both Sargon and the long line of kings of Kish who had preceded him.

In short, there was clearly something very special about the kingship of Kish

, albeit that it is difficult to establish the reason for this, not least because:

very few of the Kishite kings who found their way into the USKL also appear in other surviving sources: and

Perhaps more surprisingly, very few of the rulers who are known to have used the title ‘King of Kish’ (alone or with one or more other titles) also found their way into the USKL.

To take this further, we need to look at the other surviving sources that throw light on the early history of Kish.

The surviving USKL text is arranged in three columns on each side of this tablet fragment (with that on the reverse sometimes continuing onto the bottom). Since the opening and closing lines of the original text survive, we know that:

-

✴it begins (at obverse, col. 1, line 1) with the claim that:

-

“After kingship was brought down from heaven, Kish was king. In Kish, Gushur ruled for 2,160 years”, (see the translations by Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, 2010, at p. 231 and Gösta Gabriel, 2023, referenced below, at p. 247); and

-

✴it ends with:

-

•the name of Ur-Namma, the founder of the ‘Ur III’ dynasty (reverse, col. 3, lines 21-2); and

-

•the scribe’s dedication of his handiwork to Shulgi, his king (see below).

Shulgi was the son and successor of Ur-Namma, the founder of what historians know as the ‘Ur III’ dynasty (for reasons that will become clear below).

I discuss this important recension in more detail in my page Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL): in this section, I provide a brief summary, in order illuminate the part that it subsequently played in the more complex later recensions.

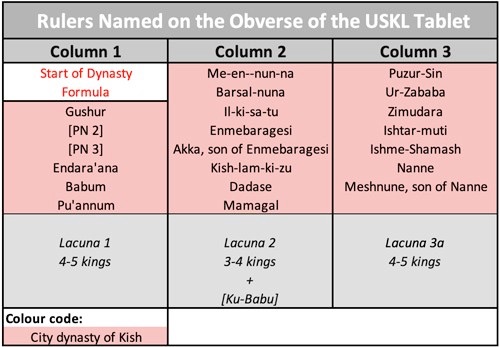

Kishite Kings in the USKL

As indicated in the table above, the surviving text on the obverse of the USKL tablet includes the opening declaration quoted above, followed by the names of 21 rulers of Kish (each of which is followed by the corresponding reign length). Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 237 and note 17) labelled this list as ‘Kish A’. Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) established that the original USKL text had originally started with a list of about 30 kings of Kish:

-

✴starting with Gushur (in time immemorial); and

-

✴probably ending with the otherwise unknown Meshnune, son of Nanne.

This ‘Kish A’ list represented about 40% of the total number of kings in the original text. As Steinkeller pointed out (at p. 284), the main structural difference between the USKL on the one hand and all of the later later SKL recensions on the other, is that in the latter, the USKL ‘Kish A’ list was sliced up into three or four segments separated by ‘intervening dynasties’ from Ur, Uruk and other city-states.

References

Gabriel, G. I.,"The ‘Prehistory’ of the Sumerian King List and Its Narrative Residue", in:

Konstantopoulos G. and Helle S., “The Shape of Stories”, (2023) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 234-57

Steinkeller P., ‘The Sargonic and Ur III Empires’, in:

Bang P. F. et al. (editors), “The Oxford World History of Empire (Volume 2): The History of Empires”, (2021) New York, at pp. 43-72

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2017) Boston and Berlin

Marchesi G., “The Sumerian King List and the Early History of Mesopotamia”, in:

Biga M. G. and Liverani M. (editors.), “Ana Turri Gimilli: Studi Dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer da Amici e Allievi”, (2010) Rome, at pp 231-48

Glassner J.-J., “Mesopotamian Chronicles”, (2004) Atlanta GA

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-292

Jacobsen T., “The Sumerian King List”, (1939) Chicago IL

Langdon S. H., “The H. Weld-Blundell Collection in the Ashmolean Museum: Vol. II: Historical Inscriptions, Containing Principally the Chronological Prism (WB. 444)”, (1923) London