Sumerian King List (SKL)

Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: USKL I: Putative Kishite King List (KKL)

Topic: USKL II: Putative Sargonic King List

Sumerian King List (SKL)

Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: USKL I: Putative Kishite King List (KKL)

Topic: USKL II: Putative Sargonic King List

Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

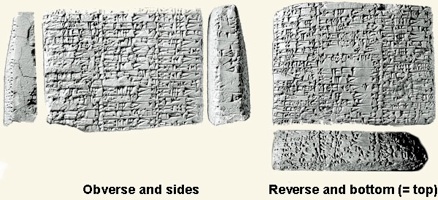

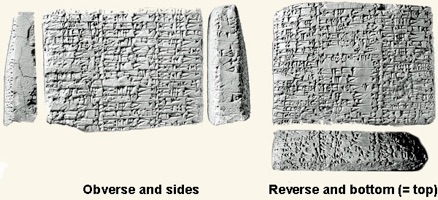

Surviving fragments of Shulgi’s Sumerian King List (USKL): image adapted from CDLI: P283804

As we have seen, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003) published the earliest known version of the Sumerian King List (SKL), which is usually referred to as the USKL because it was composed during the reign of the ‘Ur III’ king Shulgi (ca. 2100 BC). The text in question was inscribed on part of a clay tablet of unknown provenience, which was (as it still is) in a private collection:

✴Steinkeller provided a transliteration and an important initial commentary on the text and its relationship to the younger recensions of the SKL.

✴A transliteration and photographs are also available on line at CDLI: P283804): in the sections below, references to specific columns and lines of the USKL use the numbering system of the CDLI composite.

✴Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) is about to publish an updated critical edition of and associated commentary on all of the known SKL recensions, including the USKL.

The surviving USKL text is arranged in three columns on each side of this tablet fragment (with that on the reverse sometimes continuing onto the bottom). Since the opening and closing lines of the original text survive, we know that:

✴it begins (at obverse, col. 1, line 1) with the claim that:

“After kingship was brought down from heaven, Kish was king. In Kish, Gushur ruled for 2,160 years”, (see the translations by Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, at p. 231 and Gösta Gabriel, 2023, referenced below, at p. 247); and

✴it ends with:

•the name of Ur-Namma, the founder of the ‘Ur III’ dynasty (reverse, col. 3, lines 21-2); and

•the scribe’s dedication of his handiwork to:

“... [the divine] Shulgi, my king [who was Ur Namma’s son and successor]: may he live until distant days (translation based on that by Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 269).

From the degree of curvature of the surviving part of the tablet:

✴Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at pp. 268-9) estimated that the surviving text represents about half of the original; while

✴Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 237 and note 15) estimated that it represents slightly more than this (about 60% of the original).

In what follows, I adopt the more recent estimation.

Surviving USKL Text

The summaries of the text tabulated below are largely based on Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming): as in the previous page, I would like to express my gratitude to him for allowing me to read a pre-publication copy.

Obverse

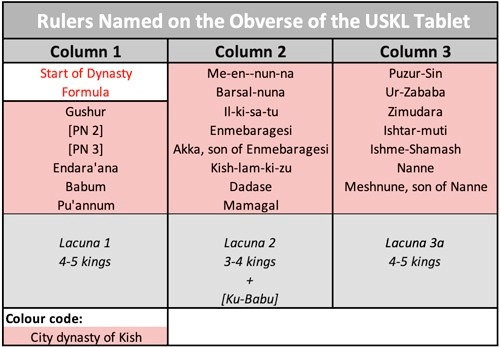

Table 1

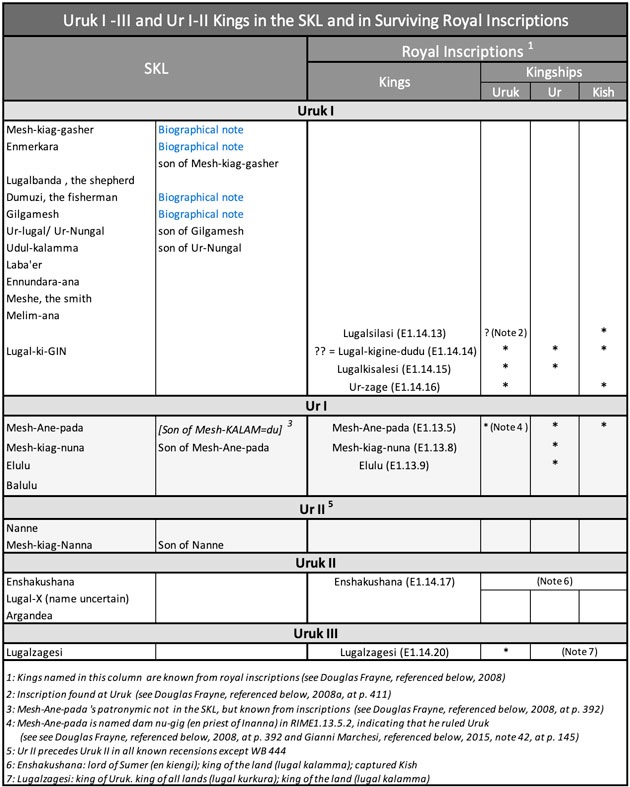

As indicated in the table above, the surviving text on the obverse of the USKL tablet includes the opening declaration quoted above, followed by the names of 21 rulers of Kish (each of which is followed by the corresponding reign length). Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. ) labelled this list as ‘Kish A’.

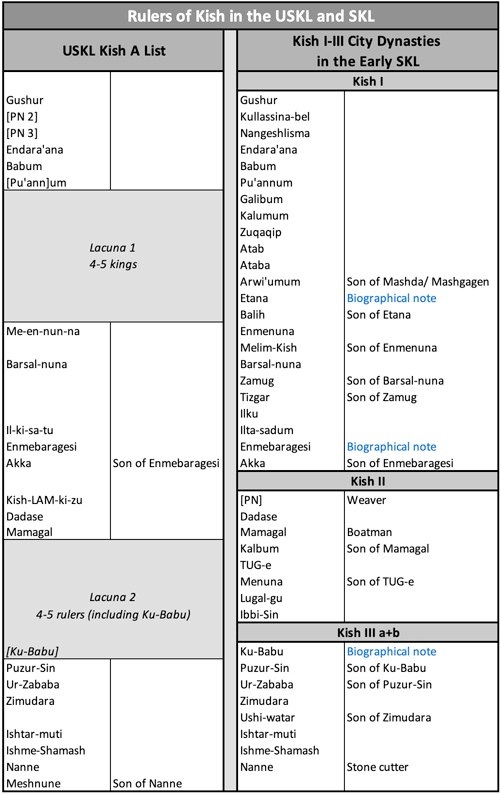

Table 2

Although (as shown in Table 2), the USKL Kish A list was split into three separate city dynasties in the early SKL recensions, and these three lists were also extended and elaborated, almost all of the USKL rulers can also be identified in the SKL. This allows us to make reasoned attempts the reconstruct the the original text in the two USKL lacunae . For example, as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) pointed out:

✴the last ruler in column 2 was almost certainly Queen Ku-Babu, since:

•the first line of column 3 records a reign of 100 years, which corresponds to the length of her reign in the SKL; and

•this is followed by Puzur-Sin, who immediately followed Ku-Babu in the early SKL recensions; and

✴since:

•Nanne (the penultimate king of the USKL Kish A list) is the last Kish III a+b king n the SKL; and

•Meshnune (identified as his son in the USKL) is otherwise unknown;

the likelihood is that Meshnune was the last of the Kish A kings the USKL.

In other words:

✴we might reasonably assume that the USKL began with a list of about 30 Kishite rulers, from Gushur to Meshnune; and

✴this list was extended to some 40 rulers between Gushur and Nanne in the SKL.

Reverse

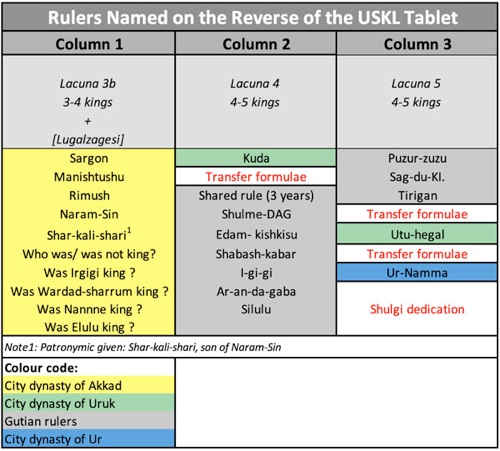

Table 3

Lacuna 3a and Lacuna 3b

Table 4

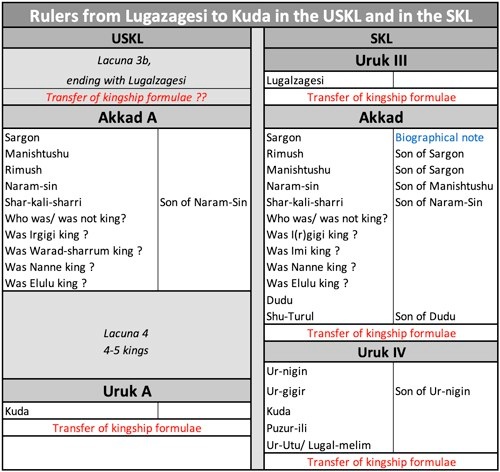

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) observed that the completion of what I have labelled Lacuna 3a (see Table 1) and Lacuna 3b (see Table 3) is extremely problematic. However, as he pointed out, we at least know that the last king in Lacuna 3b must have been King Lugalzagesi of Uruk, whom Sargon of Akkad (the first king named in the surviving text of the reverse) famously defeated, thereby becoming the king of both Akkad and Sumer. Steinkeller (as above) considered (at pp. 274-5) the possibility (his ‘option a’) that all of the kings in this long lacuna were kings of Uruk. However, he had two problems with this option:

✴he estimated that there would not have been room for all of the 15 other kings of Uruk who were named before Lugalzagesi in the SKL (12 in the Uruk I dynasty and 3 in the Uruk II dynasty - see Table 4); and

✴the inclusion of the earliest of them, all of whom were given ‘superhuman’ reigns in the SKL, indicating that they belonged to the mythical past) would have violated:

“... the diachronic principle to which the USKL otherwise religiously subscribes”.

However, he also rejected other options based on the SKL (his options b and c), and observed that:

“... there seems to be no possibility of resolving these questions at this time.”

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, note 16, at p. 237) argued that:

“Uruk is the most likely candidate for [reconstructing this lacuna, which he labelled the ‘Uruk A*’ list]. This [putative city dynasty] ... probably did not include its first five [Uruk I kings in the SKL]: Mesh-kiag/kin-gasher; Enmerkara; Lugalbanda; Dumuzi; and Gilgamesh.”

In Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming), he also argued for the omission of the next two Uruk I kings, Ur-lugal and Udul-kalama, who were both descendants of Gilgamesh. In this scenario, the long lacuna therefore contained:

✴the last four SKL Uruk I kings;

✴the three SKL Uruk II kings; and

✴Lugalzagesi (the sole SKL Uruk III king);

whom Gabriel assumed would be easily accommodated (along with two sets of ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae) in the lacuna between Meshnune and Sargon. In my view:

✴Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023) is probably correct in his observations that:

•Uruk is the most likely candidate for the ‘dynasty’ of the kings in this long lacuna in the USKL; and

•there were probably about nine of them (see p. 244); and

✴Piotr Steinkeller is certainly correct in his observation that Lugalzagesi must have been the last of them.

However, I think that this “Uruk A* list almost certainly included (and probably began with) Gilgamesh, the famous hero of Uruk. This, of course, means that we must abandon the assumption that the USKL was structured of the diachronic principle throughout. Furthermore, as is clear from Table 4, a number of rulers of Uruk who are known from surviving inscriptions, ought to be considered as candidates for this list. I will return to this ‘embarrassment of riches’ below.

Dynasty of Akkad

Table 5

As noted above, the first name in the surviving part of the reverse of the USKL tablet is that of Sargon of Akkad, who is the first securely historical figure to appear in the surviving text. Since Sargon’s victory over Lugalzagesi of Uruk would have been a key event in the ‘story’ presented in the USKL, it is unfortunate that the lines that would have documented the transfer of the kingship between them have been lost. In fact, as is clear from Table 3, the surviving text includes only one set of formulae that relate to the transfer of kingship between Mesopotamian (as opposed to Mesopotamian and Gutian) kings: in this case, which refers to the transfer from kingship from Utu-hegal of Uruk to Ur-Namma (reverse, column 3, lines 15’-22’), we read that:

“In Uruk, Utu-hegal ruled for 7 years.

Uruk was struck with weapons [and] the kingship was carried to Ur.

At Ur, Ur-Namma ruled for 18years”, (reverse, column 3, lines 15’-22’).

It is possible that similar formulae were used at the end of Lacuna 3b in relation to the transfer of kingship from Lugalzagesi to Sargon, although it seems to me that there must have been some acknowledgement here that Sargon had already conquered Kish. Interestingly, we read in the biographical note that introduced Sargon in the SKL (at lines 266-71) that:

“Sargon, whose father was a gardener, the cupbearer of (king) Ur-Zababa, (was thereafter) the king of Akkad, the one who built Akkad [and] was king [there].”

As we have seen, Ur-Zababa was recorded as a king of Kish in both the USKL and the SKL (see Table 2).

As Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, Table 5, at p. 18) demonstrated, the surviving list of kings of Akkad in the USKL is reasonably consistent with that in the relevant recensions of the SKL, except that the order of the reins of Sargon’s sons, Rimush and Manishtushu, are reversed (probably erroneously) in the USKL. These two kings are followed by Naram-Sin and then Shar-kali-sharri: he is the third and last ruler in the USKL to be given a patronymic, Shar-kali-sharri, son of Naram-Sin.

From the drafting of the USKL, it is clear that the stability of the Akkadian ‘empire’ was undermined after the reign of Shar-kali-Sharri (Sargon’s great grandson), when the compiler of the USKL prefaced the with the rhetorical question:

“ma-an-nu shar-ru-um: ma-an-nu la šar-ru-um ?”, (Who was king: who was not king ?).

Interestingly, as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 279) observed, in the USKL, this question is written in Akkadian, although, as Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) notes, in later recensions, it is written either partly or wholly in Sumerian. Scholars oftern refer to this period as the ‘period of confusion’.

Lacuna 4 and King Kuda of Uruk

TAs set out in Table 5, the surviving USKL text is broken before the two last Akkadian kings record in the SKL:

✴Dudu; and

✴his son, Shu-Turul.

Both of these kings (who ruled after the initial ‘period of confusion’) are known from royal inscriptions (see Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 1993, at pp. 210-7). Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 275) reasonably argued that they would have been the first named kings in Lacuna 4.

Steinkeller (as above) also observed that the first surviving name in the surviving part of reverse column 2 is that ot Kuda, the third of the Uruk IV kings in the SKL. We might therefore (again following Steinkeller) assume that, in the original USKL text, Shu-Durul of Akkad was followed by:

✴formulae for the transfer of kingship from Akkad to Uruk; and

✴the first three Uruk IV kings from the SKL:

•Ur-nigin;

•Ur-gigir; and

•Kuda (as in the surviving text).

Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993, at pp. 274-7) recorded epigraphic evidence for the reigns at Uruk of Ur-nigin, Ur-gigir and Kuda.

If the reconstruction of Lacuna 4 set out above is correct, then, at least in this text:

✴Ur-nigin of Uruk apparently threw off the hegemony of Shu-Durul of Akkad; and

✴Uruk then remained independent until Kuda was defeated by the Gutians.

The Gutians

We now come to the first surviving ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae in the surviving text of the USKL (see Table 3): in the reign of Kuda:

“Uruk was struck with weapons.

Its kingship was carried to the ummanum (the Old Akkadian word for horde or army).

The ummanum had no king: they ruled themselves (shared command ??) for three years.

In the SKL (at lines 307-8), the kingship was carried to ugnim gu-tu-um (where ugnim is the Sumerian equivalent of ummanum and gu-tu-um identifies the army in question as that of ‘Gutium’).

In the USKL, these ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae were followed by:

✴6 Gutian kings in the rest of column 2;

✴about 5 (presumably Gutian) kings in what is now Lacuna 5; and

✴3 Gutian kings in the rest of column 3, the last of whom was Tirigan (who ruled for only 40 days).

Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, referenced below, Table 7, at p. 20) compared this list with those of all the other known SKL recensions. Interestingly, these sources are remarkably consistent in recording just over 20 kings in their respective lists, almost all of whom ruled for 7 years or less, despite the fact that there is great variation between them in respect of the names of these kings and the order in which they ruled. Furthermore, the two surviving SKL recensions that are unbroken to the end of the list agree with the USKL that the last Gutian king to rule Uruk was Tirigan, who ruled for 40 days.

The USKL list of Gutians is followed by the second ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae in the surviving text : after the Gutian King Tirigan had ruled for only 40 days:

“The weapon was struck near (?) Adab.

The kingship was carried to Uruk.

In Uruk, Utu-hegal was king.”

This translation is proposed by Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 243 and notes 35-6): he noted that these ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae differ in a semantic sense from the formulation in the SKL (at SKL 332-5):

“The Gutian army (ugnim gu-tu-um) was struck with weapons.

The kingship was carried to Uruk.

In Uruk, Utu-hegal was king.”

His point was that:

“In the case of the Gutians’ defeat [in the USKL], the locative (or directive) case does not mark the object hit by the weapon, but [rather marks] the location at which the action took place. Since [a surviving royal inscription - see below - places] Utu-hegal’s final victory over the Gutians at a place close to Adab, [this particular] ‘collapse formula’ ... can be translated as:

‘The weapon was struck near (?) Adab’.”

As he pointed out (at note 36), his alternative translation removes the need to assume (with Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 276 and p. 281) that there must have been a set of ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae from the ummanum to Adab in Lacuna 5- see Table 3). Note. however, that some scholars follow Steinkeller in this respect(see, for example, Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, referenced below, Table 7, at p. 20).

Utu-hegal

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p. 122):

“As it happened, the person who managed to capitalise on Lugalzagesi’s achievement was, not unexpectedly, a northerner. His name was Sargon, and he hailed from the obscure town of Akkad, which was probably situated in the neighborhood of modern Baghdad. After he had conquered northern Babylonia, together with its traditional political center Kish, Sargon then confronted Lugalzagesi. In the ensuing war Sargon faced and overcame a formidable coalition of southern city-states led by Lugalzagesi, after which he became the master of the South as far as the Persian Gulf. This accomplishment was followed by a phase of foreign conquests, as a result of which. the first empire in history was created.”

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below 2017) at p. 194) argued that:

“As far as one can tell, the most significant difference between the [USKL] and its later version is that the former organises the events in an unmistakably linear fashion: after the kingship descended from heaven in time immemorial, it remained for thousands and thousands of years in Kish, down to Sargon’s very day. This veritable ‘Age of Kish’ was apparently followed by an Urukean interlude, with Akkad and the successive dynasties then following suit. In other words, the Ur III king list embraces a linear vision of history, which probably even reflects a chronologically correct historical sequence.”

Unfortunately, this characterisation is the result of a circular argument, because it assumes that, in the USKL, all of the now-unknown rulers of the ‘Urukean interlude’ ruled between Meshnune and Sargon, which is not necessarily the case (as discussed above).

As noted above, we have epigraphic evidence for Utu-hegal’s victory over Tirigan. This is in the form of three Old Babylonian copies of the inscription from the ‘victory’ monument of Utu-hegal. (A composite of these three Old Babylonian texts is available on-line as RIME 2: 13: 6: 4; CDLI. P433096). Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p. 11) cautioned that the late date of this evidence:

“... opens up a possibility that, despite its seemingly genuine late 3rd millennium characteristics, as pertains to its orthography and grammar, the Utu-hegal inscription may actually be a literary text that was composed subsequent to Utu-hegal’s own time.”

However, as Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, note 33, at p. 243) observed:

“... there is a close link between:

✴the events reported in [the surviving Old Babylonian copies of] Utu-hegal’s inscription; and

✴specific features of the USKL;

which suggests that there was some kind of connection between the two texts. This does not prove the historical truth of the narrated events, but it does indicate that Utu-hegal’s inscription existed in one form or another [by the time that] the USKL was compiled.”

This inscription (which is written in Sumerian) began by recording that Enlil had commanded the obliteration the name of:

“... Gutium, the fanged snake of the mountain ranges, a people who acted violently against the gods [by, inter alia] ... taking the kingship of Sumer (nam-lugal ki-en-gi-ra) away to the mountains ...”, (RIME 2: 13: 6: 4; CDLI. P433096), lines 1-6).

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 283) observed, this must refer to the change of control at Uruk that, in the USKL, had happened in the reign of king Kuda. The inscription then recorded that Enlil:

“... commissioned Utu-begal, the mighty man, king of Uruk, king of the four quarters, ... to destroy [the Gutian] name. ... Enlil commanded [Utu-hegal] to return the kingship of Sumer to its own control”, (lines 15-31).

Interestingly, the inscription also recorded that Utu-hegal’s victory over Tirigan’s army took place near Adab (see line 90). After his defeat in this battle, Tirigan escaped to Dabrum, where he was captured, and:

“... the kingship of Sumer returned to its own control”, (line 128).

In the light of his analysis, Piotr Steinkeller (as above) suggested that Utu-hegal had been responsible for the addition of:

✴the last rulers of Akkad;

✴the ‘undistinguished princelings’ of the Uruk IV dynasty; and

✴the Gutians;

to the USKL. He observed that:

“In my opinion, [the first passage from Utu-hegal’s victory inscription quoted above] proves conclusively that the tradition of the 4th dynasty of Uruk as an earlier possessor of kingship, and therefore Akkad’s direct heir, had been alive, whether in written or oral form, during Utu-hegal’s time. By this logic, [since] the Gutian interlude constituted an unlawful appropriation by a foreign party, [then], by defeating Tirigan, Utu-hegal simply restored to Uruk what had been [rightfully] hers.”

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 244) similarly concluded that:

“... the parallels between [Utu-hegal’s victory] inscription and USKL indicate that [in the USKL], the sequence:

✴Uruk A [= Uruk IV];

✴Gutium;

✴Uruk B [= Utu-hegal];

can be ascribed with reasonable certainty to Utu-hegal. He altered pre-existing concepts of the past to bolster his claim to power in [Mesopotamia], codifying these into [an early] recension of the SKL that has not survived, but whose structure was integrated into the USKL.”

It seems to me that this putative ‘Utu-hegal recension’ of the SKL might also have contained the Uruk A* (= Uruk I + Uruk II) kings that were (or were probably) named in the USKL since, in his victory inscription, Utu-hegal claimed that:

“The god Gilgamesh, son of the goddess Ninsun, has assigned him (Dumuzi) to me as bailiff/ deputy (mashkim)”, (lines 61-3).

As Dina Katz (referenced below, at p. 31) argued:

“The appearance of Gilgamesh in this context indicates not only that Utu-hegal knew the tale of Gilgamesh' war of liberation [of Uruk from the hegemony of Kish], but also that his achievement was an inspiration for Utu-hegal in his own war”.

The point here is that of tale of ‘Gilgamesh' war of liberation’, which described how this mythical hero liberated Uruk from the hegemony of Kish, was definitely known at the court of Shulgi, in both:

✴a praise poem of Shulgi known as ‘Hymn O’ (lines 56-60, see the translation by Ludek Vacin, referenced below, at p. 224), in which Gilgamesh liberates Uruk from the hegemony of King Enmebaragesi of Kish; and

✴the Sumerian poem known as ‘Gilgamesh and Akka’, one of the five known Sumerian poems about the hero Gilgamesh, in which his adversary is now Enmebaragesi’s son and successor, Akka;

both of whom are included in the Kish A list (see column 2 of the obverse in the table above). However, Utu-hegal’s victory inscription arguably suggests that he was aware of a similar tradition and, if so, the it is entirely possible that the putative ‘Utu-hegal recension’ of the SKL described (inter alia) all of:

✴Gilgamesh’s liberation of Uruk from the hegemony of Kish (later incorporated in Lacuna 3a on the obverse of the USKL);

✴Ur-nigin’s liberation of Uruk from the hegemony of Akkad (later incorporated in Lacuna 4 of the reverse); and

✴Utu-hegal’s liberation of Uruk from the hegemony of Gutium (later incorporated in column 3 of the reverse).

Kish A List

The opening lines of the USKL record, somewhat surprisingly, that:

“‘When kingship (nam-lugal) came down from heaven, (the city of) Kish was king; in Kish, Gusur exercised (kingship) for 2,160 years”.

As we have seen, Gushur is followed by about 30 other kings of his ‘Kish A’ dynasty, the last of whom is named as Meshnune, son of Nanne (at obverse col. 3, lines 14-16). Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023 at p. 244) argued that this list must have been based on the Kishites’ own historiographical tradition, in which case:

“... the first [precursor] of what would become the [USKL] was most likely written in Kish before ca. 2350 BC.”

I discuss this putative Kishite king list (hereafter referred to as the KKL) in my page on the Kishite precursor to the USKL.

This immediately raises the question of why the USKL started with such a long list of kings of Kish. Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 282) argued that no Sumerian ruler would have:

“... had any part in a project that assigns much of the past glory to Kish, ... This leaves us with only one possible agency [for the Kish A list]: Sargon [of Akkad and his successors, who would] have had an obvious interest in promoting the idea that Kish remained the seat of kingship from time immemorial down to Sargon’s own day. In such a scheme of history, Akkad became a natural heir and successor to Kish ...”

He elaborated on this in a later paper (Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2017, at p. 40), where he argued that the precursor of the USKL:

“... was probably written down in Sargonic times, with an express objective of demonstrating that ... the Sargonic dynasty was a continuation of the kingdom of Kish. In other words, this hypothetical [Sargonic king] list was, in its essence, a linear history of the northern Babylonian monarchy. If so, this ‘history’ would have been part of the ideological innovations that the Sargonic kings introduced to foster the idea of a unified Babylonian state, thus radically differing from the traditional, Sumerian types of historical records.”

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 282) suggested that this precursor was possibly composed during the reign of Sargon’s grandson, Naram-Sin. I discuss the way in which the KKL seems to have evolved into a less ‘localised’ king list in the Sargonic period in my page on the Sargonic precursor to the USKL.

Uruk, A* Uruk A and Uruk B Lists

Uruk A* Lacuna

As mentioned above, the ‘Kish A’ list in the surviving USKL tablet was followed by a lacuna that probably accommodated the names of nine ‘Uruk A* kings. As Poitr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) observed, since the surviving text restarts with the name of Sargon of Akkad, it almost certain that the last of the nine names in the lacuna was that of King Lugalzagesi of Uruk. (This hypothesis arises from the fact that it was Sargon’s victory over Lugalzagesi that led directly to his (Sargon’s) hegemony over Sumer, as celebrated in his triumphal royal inscriptions). Since, as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) observed, the full completion of this lacuna is extremely problematic, the subject is best deferred until the structure of the rest of the text has been investigated.

Uruk A and Akkad: the Akkadian Interlude

The first line after the Uruk A* lacuna recorded that:

“Sargon, in Akkad, ruled for 40 years”, (reverse col. i, lines 6’-7’)”.

This was followed by:

the similar records of 8 other Akkadian kings before the text was broken again (at reverse col. 1, line 21’);

a lacuna that probably recorded:

two more Akkadian kings;

‘transfer of kingship’ formulae (see below); and

two of Steinkeller’s ‘undistinguished princelings’ of Gabriel’s ‘Uruk A’ dynasty; and

Kuda, the last of these ‘Uruk A princlings’ (at reverse col. 2, line 12’-13’).

In short, in this representation of Sumerian history, the Akkadian city dynasty seems to have occupied an interlude between two kings of Uruk:

Lugalzagesi; and

a predecessor of Kuda (probably Ur-nigin, known from the SKL ).

Uruk B (Utu-hegal) and Gutium: the Gutian Interlude

We now come to the first surviving ‘transfer of kingship’ formula in the USKL, in which we read that, in the reign of Kuda:

“Uruk was struck with weapons. The kingship was carried to the ummanum (the Old Akkadian word for horde or army)”, (reverse column 2, lines 14’-16’).

As we shall see, this unnamed army was that of the Gutians (mentioned above). Apparently, initially:

“The ummanum had no single King. They ruled themselves (i.e., their senior commanders shared rule ??) for three years”, (reverse column 2, lines 17’-18’).

This was followed (at reverse column 2, lines 19’ - reverse column 3, lines 11’) by a list of about 20 Gutian rulers, the last of whom, Tirigan, had ruled for only 40 days when:

“The weapon was struck near (?) Adab”, (reverse column 3, line 12’: for this translation, see Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 243 and notes 35-6).

“The kingship was carried to Uruk, [where] Utu-hegal was king”, (reverse column 3, lines 13’-16’).

Thus, the Gutian ‘dynasty’ was sandwiched between:

the ‘Uruk A’ king Kuda; and

the ‘Uruk B’ king Utu-hegal.

Utu-hegal

As Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 243) pointed out, we have the evidence of Utu-hegal’s own account of his victory over the Tirigan: this comes in one of his royal inscriptions (translated by Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 1993, at pp. 285-7), which is known from three Old Babylonian copies. It begins with the assertion that:

“ ... (as for) Gu[tium], the fanged serpent of the mountain, who acted with violence against the gods, who carried off the kingship of Sumer (nam-lugal ki-en-gi-ra) to the mountains, ... the god Enlil, lord of the foreign lands, ordered Utu-hegal, the mighty man, king of Uruk, king of the four quarters, the king whose utterance cannot be countermanded, to destroy their name”, (lines 1-14).

Utu-hegal then sought the help of his patron goddess, Inanna, explaining to her that:

“... Enlil has [ordered me] to bring back the kingship of Sumer”, (lines 29-30).

He then announced to the citizens of Uruk that, inter alia:

“[Enlil] has given Gilgamesh, the son of Ninsun, to me as deputy”, (lines 62-64).

Dina Katz (referenced below, at p. 31) argued that this reference to Gilgamesh:

“... indicates not only that Utu-hegal knew the tale of Gilgamesh' war of liberation [from Kish], but also that [Gilgamesh’s] achievement was an inspiration for Utu-hegal in his own war.”

We then learn that, at daybreak on the day of the main battle:

“... [Utu-hegal proceeded] (to a point) upstream from Adab. ... In that place, he laid a trap against the Gutians (and) led (his) troops against them. Utu-hegal, the mighty man, defeated their generals. Then Tirigan, king of Gutium, fled alone on foot”, lines 90-107).

Tirigan was soon captured and:

“... [Utu-hegal] brought back the kingship of Sumer”, (line 129).

If we compare this text with the transfer formulae of the USKL, we can see the nature of kingship that passed from Kuda to Gutium and then returned to Utu-hegal: it was specifically the kingship of Sumer (nam-lugal ki-en-gi-ra). As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 283) pointed out:

“By this logic, the Gutian interlude constituted an unlawful appropriation of kingship by a foreign party; and so, by defeating Tirigan, Utu-hegal simply restored to Uruk what had been rightfully hers.”

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 283) argued that:

“The fact that the USKL includes [three Uruk A] kings, who were without doubt undistinguished princelings of purely local significance, is a strong indication of the Urukean bias of [the source for this part of the USKL], and points to Utu-hegal [himself its author].”

This hypothesis was accepted (for example) by Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at pp. 242-3). In this context, as Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993, at p. 280) observed:

“Noteworthy is Utu-hegal's adoption of the title 'king of the four quarters' last used by Naram-Sin [and then by the otherwise unknown Gutian ruler Erridu-pizir]”.

In fact, this title was also used by the Elamite King Puzur-Inshushinak, who was Utu-hegal’s contemporary and (as we shall see) probably occupied Akkad at this time. Interestingly, Puzur-Inshushinak was named as the 12th and last king in the so-called Awan King List (see Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at pp. 23-4), suggesting that both Utu-hegal and Puzur-Inshushiak had been ‘inspired’ to sponsor king lists by Naram-Sin’s example, (albeit that neither of them could match Naram-Sin in the breadth of his hegemony, which included both Akkad and Sumer).

Ur A Dynasty (Ur-Namma)

The end of the USKL text represents something of an anti-climax: we read (at reverse column 5, lines 13’-18’) that, during the reign of Utu-hegal:

“Uruk was struck with weapons, [and] the kingship was carried to Ur, [where] Ur-Namma ruled for 18 years”, (reverse col. 3, lines 17’-22’).

Somewhat surprisingly, this might been the only reference to Ur in the entire USKL text (which means that both the Ur I and Ur II city dynasties might have been later additions - see below).

As noted above, the USKL record of Ur-Namma was followed the scribe’s dedication to:

“... [the divine] Shulgi, my king: may he live until distant days”, (translation based on that by Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 269).

This indicates that the text was compiled while Shulgi was still alive. In fact, we can probably be more precise: Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 269) argued that, since Shulgi was given a divine determinative in this dedication, it must have been compiled at some time between:

his 20th regnal year (the approximate date of his deification); and

his 48th regnal year (the approximate date of his death).

Furthermore, although, as he observed that it is theoretically possible that the text on the only known USKL tablet is a later Ur III copy of the original, he argued that:

“... by all indications, Shulgi was still alive when [the surviving text] was written down, as the invocation suggests.”

Structure of the USKL: Analysis and Conclusions

Summary of the proposed stages in the evolution of the USKL by

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, Table 10.3, at p. 245)

In the table above, Gösta Gabriel summarised his model of the stages in which the putative Kishite King List (KKL) evolved over time so that it eventually formed the basis of the Kish A list at the start of the USKL. He concluded (at p. 247) that the message of this list in its original form was that:

“The divine gift of kingship guaranteed stability, and the gods established Kish as the eternal capital of the country. The long-lasting nature of the city allowed for the continuity of this political constellation beyond the lifespan of its individual mortal kings.”

He then argued that: :

a Sargonic version (see his section 4.2):

added Akkad and possibly Uruk A* to the KKL: and

fundamentally changed its character by:

introducing the concept that the god-given kingship could be moved from Kish to other cities; and

broadening the geographical focus of the list (which now included Kish, Akkad and possibly Uruk); and

a subsequent version compiled under by Utu-hegal (see his section 4.3):

added Uruk A, Gutium and Uruk B to the list; and

made further fundamental changes by creating an ‘epochal threshold’ between:

the long, uninterrupted reign of the Kish A kings; and

the unstable Urukean hegemony, which was interrupted:

first by the Akkadians; and

then by the Gutians;

albeit that kingship always returned to its rightful location, Uruk.

In fact, it seems to me that there is a good case here for crediting the addition of the Uruk A* dynasty not to the Sargonic but to the Utu-hegal ‘precursor of the USKL’). However, if we do make that change, then we are actually looking at two unrelated king lists:

a Sargonic list, which established Sargon and his successors at Akkad as the legitimate heirs of Gushur at Kish; and

Utu-hegal’s list, which established Utu-hegal himself as the legitimate holder of he kingship of Sumer (nam-lugal ki-en-gi-ra) and, quite possibly, as the heir of Gilgamesh.

This hypothesis is consistent with an observation of Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p. 37, who noted that this version:

“... appears to have differed significantly from the later redactions, in that it centred on the dynasty of Kish as a direct predecessor of the Sargonic kingdom. In other words, it propagated the idea of a single northern monarchy, which commenced in Kish at the dawn of history, and later continued in Akkad with Sargon and his successors.”

Thus, we have further support for the hypothesis that there were two separate precursors of USKL:

a king list written in what we call Old Akkadian and compiled in the Sargonic period (quite possibly under the auspices of Naram-Sin), which described a single northern monarchy dating back to Gushur; and

another written in Sumerian under the auspices of Utu-hegal, which contained a list of kings of Uruk (quite possibly going back to Gilgamesh) who had legitimately held the kingship of Sumer, albeit with two ‘dynastic’ interruptions (from Akkad and then from Gutium).

I will return to this discussion in my page on the ‘Utu-hegal precursor’ to the USKL

This brings us to the role of Shulgi in the compilation of the USKL. On the basis of his analysis (as set out above), he concluded (at p. 246) that:

“... the Ur III kings only added their capital city to the end of a pre-existing list.”

However, as will be evident from my comments above, it seems to me to be much more likely that Shulgi was responsible for the creation of a completely new type of Mesopotamian king list, based of the fusion two unrelated king lists discussed above:

one from Uruk, which probably at dated back to Gilgamesh; and

the other from Akkad, which dated back to Gushur.

The claim of the Ur III kings on on Gilgamesh is clear: as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at pp. 141-2) observed, surviving literary sources indicate that they:

“... traced their descent primarily to the mythical, semi-divine kings of Uruk, such as Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh. Although it may have begun already under Ur-Namma, it was only during the reign of Shulgi that this development acquired its full formulation.”

Their claim on Gushur is less clear, since scholars generally agree with Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 282 - see above), that no Sumerian ruler would have:

“... had any part in a project that assigns much of the past glory to Kish.”

However, this proposition does not take into consideration the fact that Ur-Namma gained control of a raft of territory to the north of Sumer: as Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, at p. 35) observed, shortly after Ur-Namma’s accession:

“... it would appear that [he] came into serious conflict with Elamite troops in the Diyala region. The evidence for this assertion comes from an Old Babylonian copy of a ... royal inscription of Ur-Namma that was found at ancient Isin. The inscription reads in part:

“(I), Ur-Namma, mighty man, king of Ur, king of the lands of Sumer and Akkad, dedicated (this object) for my life. At that time, the god Enlil gave (?) ... to the Elamites. In the territory of highland Elam, they (Ur-Namma and the Elamites) drew up (lines) against one another for battle. Their (??) king, Puzur-Inshushinak, ... (the cities of) Awal, Kismar, Mashkan-sharrum, the lands of Eshnunna, the lands of Tuttub, the lands of Simudar, the lands of Akkad, all the people ...”, (see also RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 29, lines 11-23).

It seems to me that, once Ur-Namma had ‘liberated’ Akkad from Puzur-Inshushinak, he had a reasonable ‘claim’ on Sargon and his successors, and, through him, on Gushur.

Utu-hegal’s situation had been very different: as Gösta Gabriel recognised (at p. 244), there is no evidence that (during what was probably a reign of only 7 years) his political influence ever extended beyond southern Mesopotamia. It is true that, after his defeat of the Gutians, he adopted the title ‘king of the four quarters’, implying that he was the ‘new Naram-Sin’, but this claim must have referenced his recent military success, rather than the extent of the territory that he controlled. There is thus no obvious reason why he would have wished to trace his kingship back before Gilgamesh, who (in Urukean tradition) had liberated Uruk from the hegemony of King Akka of Kish.

The diagram above summarises my suggested model for the stages that led to the compilation of the USKL:

an early king of Akkad (quite possibly Naram-Sin) added the name of Sargon and his successors to the pre-existing KKL, thereby propagating the idea of a single northern monarchy; and

Utu-hegal, after his victory over Tirigan, compiled an Urukean king list, quite possibly extending back to Gilgamesh, punctuated by two ‘intervening dynasties (Gutium and Akkad), thereby propagating the idea that the recent return of Uruk of the kingship of Sumer washad been pre-ordained.

Once Ur-Namma had ‘liberated’ Akkad from the hegemony of Puzur-Inshushinak, it became possible for him to represent himself as the ‘new Sargon’ (ruling both Sumer and Akkad) and thus the rightful heir of both Gushur and Gilgamesh.

It is, of course, possible that Ur-Namma’s control of Akkad was somewhat tenuous: as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at pp. 124-5) observed:

“The true greatness of the [Ur III] dynasty came with Shulgi, ... During the second decade of [his] reign, there began a phase of territorial expansion, which led to the formation of a mini-empire. These foreign conquests were accompanied at home by a massive program of political, economic, and administrative reforms, which transformed Babylonia into a highly centralised, patrimonial state. Alongside these institutional changes, there came about various ideological transformations, the most momentous of which was the deification of Shulgi, ... [an] event that can approximately be dated to [his] 20th regnal year ...”

He added (at p. 126) that:

“In my view, it is certain that, in deifying himself, Shulgi drew directly on the example of Naram-Sin.”

As we have seen, the USKL was compiled at some time after this deification, and Shulgi’s scribe explicitly referred to it. It seems to me that this would have been an extremely appropriate point in time for the compilation of what we know as the USKL. I will return to this discussion in my page on Shulgi and the USKL,

USKL Recension

Surviving part of the tablet containing the Ur III recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL):

the tablet is in a private collection and the image adapted from CDLI: P283804

In 2003, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below) published what was (and is still) the earliest known version of the SKL, which is on a clay tablet that was (and is still is) in a private collection: he provided a transliteration of and an important initial commentary on the text, and a transliteration and photographs are also available on line at CDLI: P283804. In what follows, references to specific lines in these texts adopt the numbering system used by the CDLI.

Since the final lines of the text are complete, we know that the scribe dedicated his handiwork to:

“... [the divine] Shulgi, my king: may he live until distant days (see, for example, the translation by Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 269).

As he pointed out:

“... by all indications, Shulgi was still alive when [this text] was written down, as the invocation suggests.”

He also argued (at p. 269) that, since Shulgi was given a divine determinative in this dedication, it must have been compiled at some time between:

✴his 20th regnal year (the approximate date of his deification); and

✴his 48th regnal year (the approximate date of his death).

We can thus date this recension of the SKL to the reign of Shulgi, the son and successor of Ur-Namma, who was the founder of what we know as the Ur III dynasty and the last-named king in this recension (hereafter the USKL).

First King of Kish in the USKL and the SKL

As we have seen, the USKL began with the record of Gushur, who was king of Kish at the time that the kingship itself first descended from heaven. As it happens Andrew George (referenced below, 2020, at p. 80) recently established that Gushur also appears (named as Gushur-nishī) in the prologue of an Akkadian poem about the the longstanding rivalry between a tamarisk tree and a date palm that survives in both an Old Babylonian (ca. 1750 BC) and a Middle Assyrian (ca. 1250 BC) recension:

✴the Old Babylonian prologue (which George translated at p. 79) includes for following lines:

“To bring justice to the people <like> a judge, [the gods] named Gushur-nishi as king to govern the [people] of Kish, the black-headed race, the numerous folk. The [king] planted a date-palm in his courtyard, [and surrounded it with] tamarisk ...”; while

✴in the Middle Assyrian prologue (which George translated at p. 82), the story was elaborated as follows:

“The gods of the lands held a meeting [in which] Anu, Enlil and Ea took counsel together. Among them was seated Shamaah [and] between was seated the great Lady of the Gods. Formerly there was no kingship in the lands, and power to rule was bestowed on the gods. [However], the gods so loved Gushur-nishi [that] they decreed for him the black-headed folk. The king planted a date-palm in his palace [and surrounded it with] tamarisk.”

As Andrew George pointed out (at p. 87), this confirms that:

“In one Babylonian understanding of history, [which was adopted in the USKL and the earliest recensions of the SKL], kingship ... was bestowed first on Kish, [and] Gushur was the first king of all.”

However, an alternative ‘Babylonian understanding of history’ is adopted in the prologues of the Akkadian text known as the ‘Epic of Etana’, which survives in fragments from the Old Babylonian and the Standard Babylonian (ca. 1100 BC) periods.

✴the Old Babylonian fragment in the Morgan Library Collection records that:

“The great Anunna-gods, ordainers of destiny, sat taking counsel with respect to the land. Those creators of the world regions, establishers of all physical form, those sublime for the people, the Igigi-gods, ordained the holy day for the people. Among all the teeming peoples, [the gods] had established no king: neither headdress nor crown had been put together, nor yet had any sceptre been set with lapis. No throne daises had been constructed. Full seven gates were bolted against the hero. Sceptre, crown, headdress, and staff were set before Anu in heaven. ... (Then) did [kin]gship come down from heaven” (lines 1-14); and

✴the Standard Babylonian I text records that:

“[The gods] planned the city [Kish]. The Anunna-gods] laid its foundations. The Igigi-gods founded its brickwork [...]. Let [a ma]n be their (the people’s) shepherd, ... Let Etana be their master builder ... The great Anunna-gods, or[dainers of destinies], [sa]t holding their counsel [concerning the land]. Those who formed the four regions of the world, the right and [left] (banks of the rivers), By command of all of them, the Igigi-gods [ordained the holy day for] the peop[le]. No [king] had they [yet] established [over the teeming peoples]. At that time, [no headdress had been put together, nor crown], Nor yet [had any] sceptre [been set] with lapis. No [throne daises] whatsoever had been constructed. The seven gods barred the [gates] against the multitude. ...The Igigi-gods surrounded the city [with ramparts]. Ishtar [came down from heaven to seek] a shepherd: she sought for a king [everywhere]. Enlil examined the lofty dais [in the city ...] She [Ishtar ?] has constantly sought ... [Let] king[ship be established] in the land, let the heart of Kish [be joyful]”, (lines 1-25).

As Evelyne Koubková (referenced below, at p. 375) pointed out, it seems that Etana did not actually receive the kingship of Kish in either prologue before the story moved on to describe (at considerable length) the circumstances in which Etana found himself making three attempts to ascend to heaven on the back of an eagle. The only surviving record of Etana’s successful arrival in heaven is in the Standard Babylonian III text, which preserves two relevant fragments:

✴in the first fragment, after two unsuccessful attempts, Etana explains to the eagle that he has had a dream in which:

“We passed through the gates of Anu, Enlil, [and] Ea [and did obeisance [together] ...

We passed through the gates of Sin, Shamash, Adad and Ishtar [and did obeisance together ...

I saw a house, I opened [its] seal, I pushed the door open and went inside.

A remarkable [young woman] was seated therein, wearing a tiara, beautiful of [fe]ature,

Under the throne lions were [c]rou[ching], [and], as I went in, the lions [sprang at me].

I awoke with a start and shuddered [...]”, (lines 3’-14’); and

✴in the second fragment:

“After [Etana and the eagle] had ascended to the heaven of A[nu], [they] passed through the gates of Anu, Enlil, and Ea [and]did obei[sance to]gether.

[They then passed] through the gates of Sin, [Shamash, Adad, and Ishtar and did obeisance together].

[Etana] saw [a house, he opened its seal], he pushed [the door open] and [he went inside] ... (lines 39’-45’).

Thus as Evelyne Koubková (referenced below, at p. 376) concluded:

“At the end of the preserved text, Etana gets to the highest heaven where he meets a goddess seated on a throne with lions at her feet, undoubtedly to be identified with Ishtar [whom he had already seen in his dream]. From this, I would infer that only at the end does the hero obtain his royal insignia: until that moment, these were lying in heaven in front of the god Anu ..., and it is precisely to this place that Etana goes. Therefore, one level of the myth presents Etana’s transition into a new mode of existence, namely to the state of being king.”

Comparing the epically transmitted material with that of the Sumerian King List, two things stand out. First, the Sumerian King List does not identify Etana as the first ruler in Kish, but names him after at least nine earlier kings (Gabriel 2020, 363 f.).

Second, it is striking that the Sumerian King List mentions a line of succession before Etana. According to this source, dynastic rule seems to have begun before Etana. That kings are mentioned before him is not initially a problem, since the Sumerian King List combines and condenses various sources.27 However, with regard to the concept of rule, the existence of a line of succession among the earlier kings is problematic (cf. also Diakonoff 1959, 167). This would mean that the Sumerian King List deviates at this point from the Etana material of the epic tradition. There, the beginning of the dynastic rule is linked to Etana's ascension to heaven (see 3.1).

Shulgi’s USKL

In the sections above on the surviving USKL text, I have argued that, in compiling the original, Shulgi’s scribe would have relied on:

✴a Sargonic king list that, in its turn, had relied in part on a pre-existing list of Kishite kings in order to portray Sargon as a legitimate heir of Gushur; and

✴an Urukean king list compiled by Utu-hegal after his victory over Tirigan, in order to portray Utu-hegal as a legitimate heir of Gilgamesh.

In the following three pages, I look in more detail the these putative Kishite, Sargonic and Urukean lists in more detail.

It would be possible to argue that, having assembled these source lists, all Shulgi’s scribe had to do was:

✴to combine them in a reasonably coherent manner;

✴to add the information that, during the reign of Utu-hegal:

“Uruk was struck with weapons [and] the kingship was carried to Ur, [where] Ur-Namma ruled for [x] years”, (reverse, column 3, lines 15’-22’); and

✴to dedicate the new list to Shulgi.

However, in the last of this group of pages (which is devoted to the ‘Shulgi recension’), I argue that a good deal more than this would have been involved in creating the USKL as it has come down to us: as Ludek Vacin (referenced below, at p. 223 and note 675) observed, the ‘finished article’ is very much in accord with Shulgi’s ‘ideological self-conscience’, which is also reflected in the literary compositions that originated at his court (and, in particular, in the many poems or hymns that were written and performed in his honour).

Gabriel, G. I.,"The ‘Prehistory’ of the Sumerian King List and Its Narrative Residue", in:

Konstantopoulos G. and Helle S., “The Shape of Stories”, (2023) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 234-57

George A. R., “The Tamarisk, the Date-Palm and the King: A Study of the Prologues of the Oldest Akkadian Disputation", in:

Jimenez E. and Mittermayer C. (editors), “Disputation Literature in the Near East and Beyond”, (2020) Berlin and Boston, at pp. 75-90

Koubková E., “ Fortune and Misfortune of the Eagle in the Myth of Etana”, in

Drewnowska O. and Sandowicz M. (editors), “Fortune and Misfortune in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 60th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at, Warsaw, 21–25 July 2014”, (2017) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 371-82

Steible H. and Yıldız F., “(TS)Š 302: Eine Importtafel aus Uruk in Šuruppak ?”, in:

Sassmannshausen L. (editor), “He Has Opened Nisaba's House of Learning: Studies in Honor of Ake Waldemar Sjoberg on the Occasion of His 89th Birthday on August 1st 2013”, (2014) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 217–28

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-292

Cooper, J. S., “Reconstructing History from Ancient Inscriptions: The Lagash-Umma Border Conflict”, (1983), Malibu CA

References

Gabriel, G. I.,"The ‘Prehistory’ of the Sumerian King List and Its Narrative Residue", in:

Konstantopoulos G. and Helle S., “The Shape of Stories”, (2023) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 234-57

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2017) Boston and Berlin

Marchesi G., “Towards a Chronology of Early Dynastic Rulers in Mesopotamia”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 139-56

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 1-130

Vacin L., “Šulgi of Ur: Life, Deeds, Ideology and Legacy of a Mesopotamian Ruler As Reflected Primarily in Literary Texts”, (2011), thesis of the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London)

Marchesi G., “The Sumerian King List and the Early History of Mesopotamia”, in:

Biga M. G. and Liverani M. (editors.), “Ana Turri Gimilli: Studi Dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer da Amici e Allievi”, (2010) Rome, at pp 231-48

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Vol. 1: Presargonic Period (2700-2350 BC)”, (2008) Toronto Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-292

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Early Periods, Vol. 2: Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2334–2113 BC)”, (1993) Toronto, Buffalo and London

Katz D., “Gilgamesh and Akka: Library of Oriental Texts, Vol. 1”, (1993) Groningen