Sumerian King List (SKL)

Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: USKL I: Putative Kishite King List (KKL)

Topic: USKL II: Putative Sargonic King List

Sumerian King List (SKL)

Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: USKL I: Putative Kishite King List (KKL)

Topic: USKL II: Putative Sargonic King List

Putative Kishite King List (KKL) and the USKL

Text

p

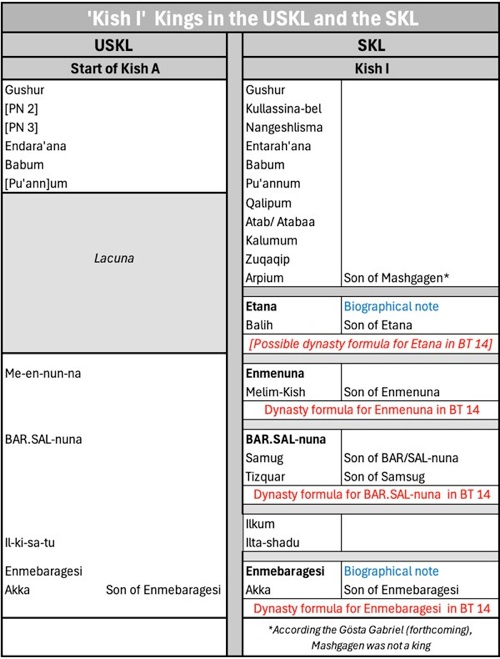

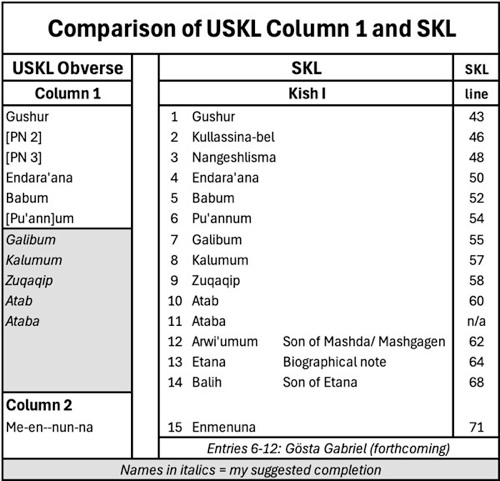

‘Kish I’ Kings in the USKL and the SKL

Table 6: Comparison of the record of the early Kish A kings in the USKL

and the corresponding ‘Kish I’ list in the SKL

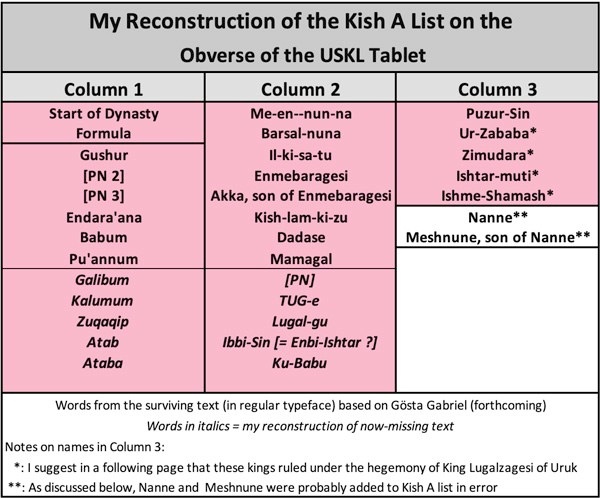

As we have seen, the USKL text begins with about 30 kings of Kish, which Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023 at p. 244) dubbed the ‘Kish A’ list. He argued that it must have been largely compiled from the Kishites’ own historiographical tradition, in which case:

“... the first recension of what would become the [USKL and subsequently the SKL would have been] was most likely written in Kish before ca. 2350 BC.”

Table 6 shows how the early part of this list was used as a basis for the SKL record of the rulers of the Kish I dynasty. As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) observed:

✴the first six Kishite kings in the USKL were directly translated into the SKL.; and

✴the text from the lacuna that followed them was probably the source for some of the SKL ‘Kish I’ kings between Pu’annum and Enmenuna.

However, this USKL lacuna could only have accommodated 5 of these seven kings, so at least two of these seven SKL kings were new additions.

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2021, at p. 324) argued that Etana would have been one of the original Kish A kings, albeit that:

“... it is certain that the narrative addition [in the SKL] reporting his ascension to heaven was only added in a later editing of the work”, (my translation).

Etana and his ascent to heaven is known from literary tradition, but, as Gabriel observed (at p. 320):

“The earliest copies of this epic tradition date from the early 2nd millennium BC; the most recent from the middle of the 1st millennium BC. All known texts are written in the Akkadian language. Since the protagonist is located in the northern Babylonian city of Kish, the material's origin from the Semitic-speaking population is obvious. This impression is reinforced by a group of non-textual sources, namely depictions on cylinder seals from the 24th century BC, [which] belong to the so-called Kingdom of Akkad, the first large territorial state in Babylonia established by Semitic-speaking rulers”, (my translation).

Actually (as discussed in a later page) there is some doubt about whether some or indeed any of these Akkadian seals do actually depict Etana (rather than just the snake and/or the eagle with which he became associated). It is nevertheless possible that Etana did indeed find his way into the USKL via the putative KKL. However, it seems to me to be more likely that the compilers of the early editions of the SKL took Etana and his son, Balih directly from the Akkadian literary sources..

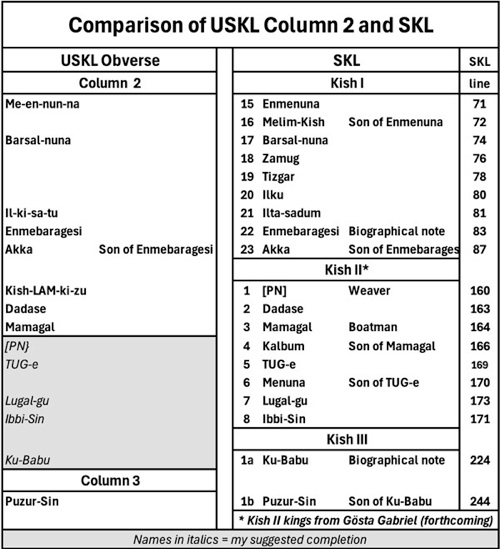

It is clear from the table above is that the USKL list from Enmenuna to Il-ki-sa-tu was greatly elaborated in the SKL:

✴Melim-Kish was introduced as the son of Me-en-nun-na (= Enmenuna), who was given a ‘familial dynastic formula’ in BT 14;

✴Samug and his son, Tizqar were also later additions, who were introduced (respectively) as the son and grandson of BAR.SAL-nuna, who was given a ‘familial dynastic formula’ in BT 14; and

✴‘Il-ki-sa-tu’ in the USKL seems to have been re-named as Ilkum and/or Ilta-shadu in the SKL.

This brings us to Enmebaragesi and his son, Akka. Enmebaragesi was possibly a historical figure who is known from two surviving royal inscriptions. However, the source of the information in the biographical note given to Enmebaragesi in the SKL (that he had defeated the Elamites) is unknown. Both men were recorded in literary sources that were current at Shulgi’s court as contemporaries of Gilgamesh, the hero of Uruk, which might explain why Akka was one of only three kings in the surviving USKL text who is given his patronymic: in other words, it is likely that the putative KKL was devoid of patronymics, in which case, the patronymic given to Akka could have come from a separate, possibly Sumerian, source.

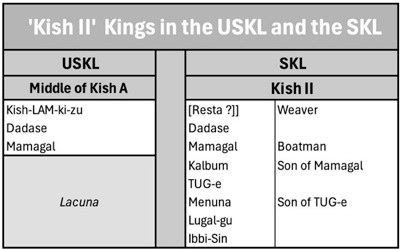

‘Kish II’ Kings in the USKL and the SKL

Table 7

In the surviving USKL, Akka was immediately followed by three more Kishite kings (named in Table 7) before a lacuna that would have accommodated 4-5 more names. It seems likely that the only changes made to the original Kish A list in the SKL was the addition of two kings, each of which was named as the son of the preceding king:

✴Kalbum, son of Mamagal; and

✴Menuna, son of TUG-e.

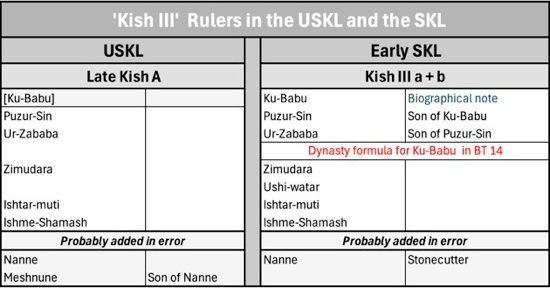

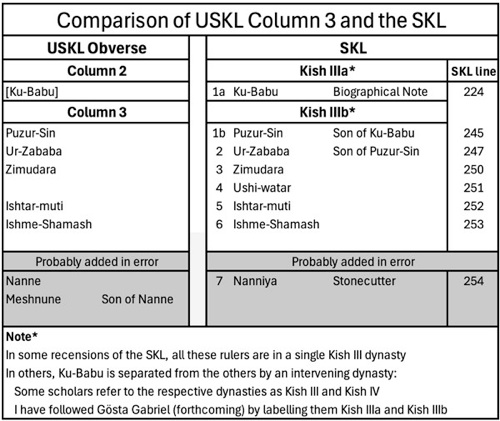

‘Kish III a+b’ Rulers in the USKL and the Early SKL

Table 8

Queen Babu was almost certainly the last ruler named in the lacuna in the surviving USKL text seen in Table 7, although it is now impossible to say whether or not she was given a biographical note here. What is clear is that she was given her own familial dynasty in the SKL, where her son and grandson are both given patronymics. The only other change made to the USKL before the entry for Nanne was the addition of a new king, Ushi-watar (this time without a patronymic).

Table 8a

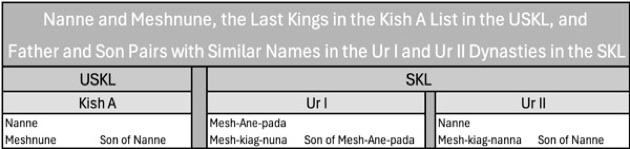

This brings us to Nanne and his son Meshnune, the last two Kish A kings in the surviving USKL text. First, as noted above (in the context of the patronymic of Akka), it is likely that, if these two kings had appeared in the putative KKL, then it is likely that Meshnune had lacked his patronymic there. However, his inclusion in the USKL is surprising, since (unlike Nanne) he was subsequently omitted from the SKL (see Table 8).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 278) offered a possible explanation for the putative addition of Nanne and Meshnune: as he pointed out, two similar father-and-son pairs of kings are recorded elsewhere in the SKL:

✴Mesh-Ane-pada (SKL 135) and Mesh-kiag-nuna, son of Mesh-Ane-pada (SKL 137-8) are named as the first two rulers of the Ur I dynasty; and

✴Nanne (SKL 194) and Mesh-kiag-nanna, son of Nann (SKL 196) are named as the first two rulers of the Ur II dynasty.

Interestingly, two relevant royal inscriptions that mention Mesanepada survive:

✴a bead found at Mari names Mesh-Ane-pada as king of Ur and the son of Mes-KALAM-dug, king of Kish (RIME 1: 13: 5: 1); and

✴a clay sealing from Ur names Mesh-Ane-pada himself as king of Kish (RIME 1: 13: 5: 2).

The point here is that, by the time of the historical Mesh-Ane-pada, the title ‘king of Kish’ seems to have become an honorific title, with the connotation ‘king of the world’, probably indicating hegemony (or at least the claim of hegemony) over the land of Sumer. This fact prompted Piotr Steinkeller (as above) to ask, rhetorically:

“Is it possible that [the USKL kings] Nanne and Meshnune are in fact Mesh-Ane-pada and Mesh-kiag-nuna of Ur, whom the USKL classified as Kishite rulers because Mesh-Ane-pada held the title of [king of Kish]? If so, [their reclassification in the SKL as Ur I kings] would be fully justified.”

In other words, it is possible that the USKL scribe:

✴had epigraphical evidence for Mesh-Ane-pada, king of Kish, and his son Mesh-kiag-nuna; and

✴abbreviated these two names as Nanne and Meshnune respectively and assumed that they had actually ruled at Kish.

This suggestion has been broadly accepted by (for example) Piotr Michalowski (referenced below, at pp. 159-60) and Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming): its corollary would be that we should probably assume that Nanne also found his way into the Kish III list in the SKL because of this error.

This brings us to Nanne and his son Meshnune, the last two Kish A kings in the surviving USKL text. First, as noted above (in the context of the patronymic of Akka), it is likely that, if these two kings had appeared in the putative KKL, then it is likely that Meshnune had lacked his patronymic there. However, his inclusion in the USKL is surprising, since (unlike Nanne) he was subsequently omitted from the SKL (see Table 8).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 278) offered a possible explanation for the putative addition of Nanne and Meshnune: as he pointed out, two similar father-and-son pairs of kings are recorded elsewhere in the SKL:

Mesh-Ane-pada (SKL 135) and Mesh-kiag-nuna, son of Mesh-Ane-pada (SKL 137-8) are named as the first two rulers of the Ur I dynasty; and

Nanne (SKL 194) and Mesh-kiag-nanna, son of Nann (SKL 196) are named as the first two rulers of the Ur II dynasty.

Interestingly, two relevant royal inscriptions that mention Mesanepada survive:

a bead found at Mari names Mesh-Ane-pada as king of Ur and the son of Mes-KALAM-dug, king of Kish (RIME 1: 13: 5: 1); and

a clay sealing from Ur names Mesh-Ane-pada himself as king of Kish (RIME 1: 13: 5: 2).

The point here is that, by the time of the historical Mesh-Ane-pada, the title ‘king of Kish’ seems to have become an honorific title, with the connotation ‘king of the world’, probably indicating hegemony (or at least the claim of hegemony) over the land of Sumer. This fact prompted Piotr Steinkeller (as above) to ask, rhetorically:

“Is it possible that [the USKL kings] Nanne and Meshnune are in fact Mesh-Ane-pada and Mesh-kiag-nuna of Ur, whom the USKL classified as Kishite rulers because Mesh-Ane-pada held the title of [king of Kish]? If so, [their reclassification in the SKL as Ur I kings] would be fully justified.”

In other words, it is possible that the USKL scribe:

had epigraphical evidence for Mesh-Ane-pada, king of Kish, and his son Mesh-kiag-nuna; and

abbreviated these two names as Nanne and Meshnune respectively and assumed that they had actually ruled at Kish.

This suggestion has been broadly accepted by (for example) Piotr Michalowski (referenced below, at pp. 159-60) and Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming): its corollary would be that we should probably assume that Nanne also found his way into the Kish III list in the SKL because of this error.

Kishite Kings in the USKL

The USKL begins with the information that:

“After kingship was brought down from heaven, Kish was king. In Kish, Gushur ruled for 2,160 years”, (see the translations by Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, at p. 231 and Gösta Gabriel, 2023, referenced below, at p. 247).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, referenced below, 2003, at pp. 269-71) observed , this was almost certainly the start of a continuous list of about 30 kings of Kish, which Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 237, at note 17) conveniently labelled as the ‘Kish A’ list:

✴19 of these kings are named in the surviving part of the USKL tablet, and almost all of them were subsequently also named in the SKL; and

✴on the assumption that there were indeed no ‘dynastic’ breaks in the list, there would have been room for about 10 more (about 5 in each of the lacunae in columns 1 and 2) in the original.

I have summarised my reconstruction of rest of the list in the table above, and will discuss this reconstruction column by column in the sections below, before moving on the final section to discuss the likely source of this list..

Obverse: Column 1

Gushur and the Foundation Myth of Kish in the USKL

In the USKL, as in every other known recension of the SKL in which Gushur ‘s record survives, he is identified as the first king of Kish, whose reign dated back to the time that kingship first descended on that city from heaven. However:

✴in the USKL, he is given a reign of 2,160 years; while

✴in the other known SKL recensions, he is always given a reign of 1,200 years.

Andrew George (referenced below, 2020, at pp. 86-7) pointed out that the correct reading of his name in the SKL was established only relatively recently: he is named as ‘Gushur’ in all but one of the known SKL recensions. The ‘odd man out’ in this respect is a recension published by Andrew George (referenced below, 2011, at p. 203, line 45), in which this first king of Kish is named Lu-Gushura.

Gushur is the only one of the first six kings in the USKL who features in the surviving Kishite literary tradition: Andrew George (referenced below, 2020, at p. 80) argued that he appears (named as Gushur-nishī) in the prologue of an Akkadian poem about the the longstanding rivalry between a tamarisk tree and a date palm. He pointed out (at p. 76) that:

“This prologue survives in three different versions on three different tablets:

✴an Old Babylonian tablet of the middle of the 18 century BC from Tell Harmal, a site in modern Baghdad;

✴a Middle Assyrian tablet of about the 13th century BC from Assur on the river Tigris below Mosul; and

✴another tablet of about the 13th century BC from Emar in Syria, on the river Euphrates, upstream of Raqqa.”

The Old Babylonian prologue (which George translated at p. 79) includes for following lines:

“To bring justice to the people <like> a judge, [the gods] named Gushur-nishi as king to govern the [people] of Kish, the black-headed race, the numerous folk. The [king] planted a date-palm in his courtyard, [and surrounded it with] tamarisk ...”

In the Middle Assyrian prologue (translated at p. 82), the story was elaborated as follows:

“The gods of the lands held a meeting [in which] Anu, Enlil and Ea took counsel together. Among them was seated Shamaah [and] between was seated the great Lady of the Gods. Formerly there was no kingship in the lands, and power to rule was bestowed on the gods. [However], the gods so loved Gushur-nishi [that] they decreed for him the black-headed folk. The king planted a date-palm in his palace [and surrounded it with] tamarisk.”

Thus, it seems that the Kishite ‘foundation myth’ at the heart of this Akkadian poem dated back at least as far as the reign of Shulgi.

An observation made by Andrew George (referenced below, 2020, at p. 87) might throw some light on the date at which this particular myth originated: he pointed out that:

“As has often been observed, many of the names of the first kings of Kish [in the SKL] are Semitic, and [the Akkadian/ Semitic] Gushshur (Most Powerful) would be a suitable fit [for the king] at the top of the list. The spelling [Gushur] would then be a secondary development.”

Walter Sommerfeld (referenced below, at pp. 534-5) argued that:

“In the ED IIIa period, [ca. 2570-2470 BC], the onomasticon shows unequivocally the preponderance of Sumerian names [at Kish]. From the following ED IIIb period, the sources are so poor that no statistically significant conclusions can be drawn from the few names in them. In the Sargonic period, [ca. 2290-2170 BC], the Semitic element has become predominant.”

Thus, it is unlikely that the ‘Gushur version’ of the Kishite foundation myth was established in the ED IIIa period. Sommerfeld also observed (at pp. 528-9) that:

“According to widely held opinions, [the Kishites’] rise to power was connected to a dominance of Semitic-speaking elites who had adopted cuneiform to put their own language in writing and at the same time had created new text genres. Also in later native historical tradition, Kish is represented as a centre of pre-eminent importance. The pseudo-historical Sumerian King List accords the city the distinction of being the first seat of kingship after the Flood, where the longest lasting dynasty of 23 [Kish I] rulers had their residence, many of whom bear Semitic names.”

This brings us back to the assertion of Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 244), who argued that the Kish A list of the USKL, which represents:

“... the first recension of what would become the [USKL and subsequently the SKL would have been] written in Kish before ca. 2350 BC.”

Other Kings in Obverse Column 1

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) observed:

✴the five kings named after Gushur in obverse column 1 of the surviving part of the USKL tablet correspond to the 2nd-6th ‘Kish I’ kings in the SKL; and

✴the first king named in obverse column 2 corresponds to Enmenuna, the 15th of these ‘Kish I’ kings.

He therefore reasonably assumed that the kings named in what is now the intervening lacuna would have also subsequently appeared among the SKL Kish I kings. More precisely:

✴he estimated that there would have been room for all eight of the SKL kings between Pu’annum and Enmenuna; while

✴Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) estimated that there would have been room for only five of them, and he suggested (with some reservation that the five kings in question would have been Ataba, Kakumum, Zuqaqip, Etana and Balih.

I assume in what follows that Gabriel’s more recent estimate is correct, but I think that we should defer the completion of column 1 until we have reconsidered the case for the inclusion of Etana, the only other one of the first 15 Kish I kings in the SKL who is also known from other surviving sources.

Was Etana Included in the USKL ?

As mentioned above, Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) included Etana in his completion of obverse: col. 1. In an already published paper (referenced below, 2021, at p. 324) paper, he also assumed that Etana was included in this list, although he added that, since the surviving text of USKL contains no biographical notes:

“... it is certain that the narrative addition [in the SKL] reporting his ascension to heaven was only added in a later editing of the work”, (my translation).

He translated this biographical addition to the SKL (at p. 326) as follows:

“Etana, the shepherd, the one who ascended to heaven, the one who had made it [kingship?] permanent in all the lands”, (SKL 64-67, my translation of Gabriel’s German).

The background to this laconic note is found in the Akkadian text known as the ‘Epic of Etana’, which only survives in fragments from the Old Babylonian, Middle Assyrian and Standard Babylonian periods. Most important for our purposes are the prologues of these texts: in particular:

✴the Old Babylonian fragment in the Morgan Library Collection records that:

“Among all the teeming peoples [the gods] had established no king: neither headdress nor crown had been put together, nor yet had any sceptre been set with lapis. No throne daises had been constructed. Full seven gates were bolted against the hero. Sceptre, crown, headdress, and staff were set before Anu in heaven. ... (Then) did [kin]gship come down from heaven” (lines 6-14); and

✴the Standard Babylonian text identifies the teeming peoples as those of Kish:

“The seven gods barred the [gates] against the multitude. ...The Igigi-gods surrounded the city [with ramparts]. Ishtar [came down from heaven to seek] a shepherd: she sought for a king [everywhere]. Inanna [came down from heaven to seek] a shepherd and sought for a king e[verywhere]. Enlil examined the lofty dais [in the city ...] She [Ishtar ?] has constantly sought ... [Let] king[ship be established] in the land, let the heart of Kish [be joyful]”, (lines 18-25).

Etana Epic I.20–23: dIŠ.TAR re-é-a [. . . ] // ù LUGAL i-še-¬i-i [ . . . ] // din-nin-na re-é-[ . . .]

// ù LUGAL i-še-[ . . . ] (‘Ishtar [looked for] a shepherd and searched for a king; Inanna [looked

for] a shephe[rd] and search[ed] for a king.’).

As Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2021, at p. 320) observed, the rest of the surviving text:

“.. records that the wife of the shepherd/king Etana is unable to bear a son. Therefore, he sets out in search of a plant [known as the ‘plant of birth’] that promises relief. Riding [on the back of] an eagle that he has rescued from a pit, he ascends to heaven... The surviving clay tablets break off completely at the point at which Etana enters a temple in heaven (presumably that of the goddess Innana/Ishtar)”, (my translation of Gabriel’s German).

Unfortunately, both of the later recensions broke off at this point, so we do not know how any of the three recensions ended. However, since Etana is succeeded by his son in the SKL (see the table above), we might reasonably assume that they all ended happily after the ‘plant of birth’ had the desired effect.

Since the biographical note attached to Etana in the SKL describes him as ‘the shepherd ... who ascended to heaven’, we can reasonably date this tradition back at least to the Old Babylonian period. However, Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2021, at p. 325) observed, there is an important difference between the Akkadian epic and the note in the SKL:

✴the epic identified Etana as the first ruler in Kish; while

✴the SKL names him after a number of earlier rulers (beginning with Gushur, who is explicitly identified as the first king of Kish).

Gabriel therefore suggested (at p. 327) that:

“Although kingship in the [SKL] already existed before Etana, [perhaps] it acquired a new quality with him, involving the concept of the dynastic transmission of power”, (my translation).

With this in mind, he returned to the identification of the ‘unnamed direct object’ of the biographical note in the SKL, which:

“... is presumably the kingship (nam-lugal). However, what is the meaning [of the claim that] Etana ‘made the kingship permanent in all lands’?”, (my translation).

His answer was that this phrase probably implies that Etana ‘made dynastic kingship [rather than kingship itself] permanent in all lands’.

This, of course, gave rise to another potential problem: in the SKL, Etana’s son, Balih, is not the first king in to be given a patronymic: in these recensions, Etana is preceded by Arwi’umum, who is variously named as the son of Mashda or the son of Mashgagen. If, as many scholars (including Thorkild Jacobsen, referenced below, at pp. 17-8 and Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) have assumed, Mashda/ Mashgagen himself had been a king, then Etana had not been the first king to pass on the kingship to his son. However, Gabriel (as above) argued that neither Mashda nor Mashgagen is named as a king in the SKL. He therefore argued that the filiation given to Balih is the first ‘royal’ filiation in the SKL and:

“For this reason, Etana's entry marks a turning point ... While he is not the first king [of Kish] in the SKL, he is given a new quality, namely as [the first dynastic king in the list]”, (my translation).

As he pointed out, in all future cases in which a kings is given a filiation, he is named as the son of the king who preceded him in the list.

It seems to me that, although this analysis provides a possible explanation of how the presence of both Gushur and Etana in the SKL could be rationalised:

✴it does not remove the problem that there were clearly two ‘competing’ Kishite foundation myths available to its compilers; and

✴it does not indicate that the ‘Etana’ myth would have been available to the compiler of the putative Kishite recension of the USKL.

In other words, the case for the inclusion of Etana (and that of his son, Bahil) in the Kish A list of the USKL has not been made.

Completion of Obverse Column 1

As far as I am aware, there are actually no clear criteria for deciding which (if any) of the 8 SKL Kish I kings between Pu’annum and Enmenuna should be rejected as a candidate for the completion of the obverse: col. 1 list. However, it seems to me that since:

✴Arwi’umum, Etana and Bahil are the only kings among the eight candidates who received either a biographical note or a patronymic in the SKL (see the table above); and

✴biographical notes are unknown and patronymics are rare in the USKL;

then, we might reasonably hypothesise that the compilers of the SKL took all of Arwi’umum, Etana and Bahil from Kishite sources that were unknown to the compilers of the USKL. I have reproduced this version of the completed column 1 in the table above.

Obverse: Column 2

Completion of Obverse Column 1

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) observed that this column contained:

✴five kings who could be identified in the latter part of the SKL ‘Kish I’ list;

✴three who could (or could probably) be identified as the first three SKL ‘Kish II’ kings.

However, four of the SKL ‘Kish I’ kings were definitely missing from the USKL:

✴Melam-kish, son of Enmenuna (SKL 72);

✴Zamug, the son of Barsal-nuna (SKL 76);

✴Tizqar, the son of Zamug (SKL 78); and

✴Ilku (SKL 80).

Furthermore, in the SKL:

✴Barsal-nuna was given a patronymic (son of Enmenuna); and

✴Enmebaragesi was given a biographical note (see below).

Thus, it is clear that the compilers of the Kishite king lists in SKL did not rely solely on the USKL for their information.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) reasonably assumed that all of the kings named in what is now the lacuna in the lower part of column 2 were Kishite rulers, and that the last of them would have been Ku-Babu since:

✴the first line of column 3 recorded a reign of 100 years, corresponding to that of Queen Ku-Babu in the SKL; and

✴the first king named thereafter was Puzur-Sin, who was identified in the SKL as her son.

In relation to the completion of this column:

✴Steinkeller estimated that there would have been room for up to seven rulers (including Ku-Babu); while

✴Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) estimated that there would have been room for only five of them (including Ku-Babu): he rejected Kalbum and Menuna on the grounds that each had a patronymic (suggesting a later addition).

On this basis, column 2 can be completed as in the table above.

Enmebaragesi and his son, Akka

Enmebaragesi is the only one of the Kishite kings named in either the USKL or the SKL who might feature in contemporary royal inscriptions: more specifically, he might be:

✴the Mebaragesi whose name appears (tout court) on a fragment of an alabaster bowl from Khafayah (ancient Tutub) in the Diyala valley (RIME 1: 7: 22: 1; CDLI. P431026); and/or

✴the Mebaragesi, king of Kish whose name appears on a similar fragment of unknown provenience (RIME 1: 7: 22: 2; CDLI, P431027).

However, his victory over Elam, which was recorded in a narrative note that was added in the SKL, is not recorded in any of our other surviving sources.

In the USKL, Enmebaragesi is followed by Akka, who is explicitly identified as his son. This is worthy of comment because, as already mentioned) the USKL (unlike the SKL) makes only sparse use patronymics. However, Akka’s patronymic in the USKL is explained because (as we shall see) Enmebaragesi and his son Akka also appear in a number of Sumerian literary texts that were of considerable importance to Shulgi: crucially, in these texts, Enmebaragesi and Akka are contemporaries of Gilgamesh, the famous hero of Uruk. Thus, as discussed in my page on the ‘Utu-hegal recension’, it is possible Gilgamesh of Uruk and Enmebaragesi and Akka of Kish all appeared in the USKL, which raises the question of how their synchronisation would have been handled.

‘Ibbi-Sin’ (SKL 171) = Enbi-Ishtar ?

In the Table 7, the name of the penultimate ruler in column 2 (SKL 171) is given as Ibbi-Sin, although this is debatable. The name of this ruler was corrupt in the 2 relevant recensions available to Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below): he argued (at p. 169) that:

“The ancient copyist apparently did not understand what he was copying. ... [It] seems highly probable that [he] was trying to render as faithfully as he could a damaged line.”

He argued that this must have been Enbi-Ishtar ( en-bí-eš18- tár), on the basis on the basis of a surviving royal inscription of King Enshakushana of Uruk that celebrated his victory over a Kishite king of this name (RIME 1: 14: 17: 1, CDLI P431228, line 10). On this basis:

✴Jean-Jacques Glassner (referenced below, 2004, at p123) suggested ‘Enbi-[Ishtar]’; and

✴Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, at p. 52) suggested ‘Ibbi-[Ishtar(?)]’.

However, Gianni Marchesi (referenced below, 2010. at p. 235) strongly disagreed: he argued that:

“Jacobsen’s belief in the general historical veracity of SKL led him to arbitrarily emend the text (or to restore broken portions of it) with the names of kings known from historical sources and to suggest unlikely ad hoc readings for some of the royal names in SKL in order to approximate the names of known historical sovereigns. So, for instance, [he] reconstructed the badly preserved name of the penultimate [Kish II king in WB 444] ... as Enbi-Ishtar, the name of the pre-Sargonic king of Kish who was defeated and taken prisoner by Enshakushana ... [The name in] WB 444 iv 31 actually reads i-bi-‹x.x.x›.”

He also referred to another relevant text that was discussed in a (then unpublished) paper by Andrew George (referenced below, 2011, at pp. 204-5, ii: 6: see also CDLI, P342704, col. 2, line 6’), where this name is transliterated as i-bi-dsue[n] and translated as ‘Ibbi-Suen’. Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) accepted this transliteration, which he translated as ‘Ibbi-Sin’. (Interestingly, Ibbi-Suen/Ibbi-Sin is also the name of the last of the Ur III kings.)

I wonder if we can dismiss Jacobsen’s suggestion so easily, since all of the surviving versions of this name could have been based on a corrupt ‘original’: after all,:

✴in the USKL, the Kishite king was immediately followed by Ku-Babu; and

✴as we shall see in the following section, she was described in the SKL as the ruler who ‘consolidated the foundation of Kish’.

It is therefore possible that Ku Babu was remembered as the queen who liberated Kish from the hegemony of Enshakushana. Furthermore, it is surely no coincidence that

✴i-bi-‹x.x.x›/ i-bi-dsue[n] appears in the SKL as the last Kish II king (except in WB 444, where he is second-to-last); and

✴Enshakushana appeared (after an ‘intervening’ king of Hamazzi and usually two ‘intervening’ kings of Ur ) as the first Uruk II king.

Obverse: Column 3

Ku-Babu, Puzur-Sin and Ur-Zababa

Ku-Babu was recorded in the SKL (at lines 224-6) as:

“... the female innkeeper who consolidated the foundations of Kish”, (translated by Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, 2010, at p. 242).

As is often pointed out, she is the only female ruler named in any of the SKL recensions.

In many of these recensions, Ku-Babu is the only ruler in what is usually designated as the Kish III dynasty and is followed by another, non-Kishite, dynasty (Akshak) before we reach Kish IV. However, Jacob Klein (referenced below) published a fragment of a recension from Nippur in which this intervening dynasty was missing: after records of the Uruk II rulers Enshakushana and Argandea and a lacuna of about 32 lines:

✴the list continued with two rulers:

•a now-unnamed son of Ku-baba (presumably Puzur-Sin); and

•Ur-Zababa, the son of Puzur-Sin; and

✴they were followed by a ‘summary of a dynasty formula’ that recorded that the dynasty of Ku-Babu had ruled for a total of 131 years (see col. VI, lines 1’-7, at p. 83).

As Klein observed (at p. 87), this indicates that, in this recension, Ku-Babu was placed:

“... at the head of [a single Kishite] dynasty, ... From the number 131 given by our text for the total of the regnal years of Ku-Baba and her two sons, we may conclude that [this recension] assigned to Ku-baba and Puzur-Sin 100 and 25 years respectively, in accordance with the majority of the other [recensions].”

More recently, Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) has established that at least two other known SKL recensions (one from Isin and one from Susa) also name Ku-babu and her successors in a single list. He proposed the notation Kish IIIa for Ku-Babu and Kish IIIb for her successors (as in the table above: see also Gösta Gabriel, referenced below, 2023, at p. 239). Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) reasonably suggested that these three SKL recensions were probably the earliest of the 24 that survive. As mentioned above, Ku-babu was also immediately followed by Puzur-Sin and Ur-Zababa in the USKL (although the dynastic links between them were not made explicit).

Ku-baba was clearly regarded (at least in the Old Babylonian period) as an extraordinary individual: not only was she the only queen recorded in the SKL, but she had also founded her own dynasty. Furthermore, as Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) argued, she must have done something very important for Kish: he noted that the Sumerian verb ge.n (to be; to make permanent), which is implicitly translated as ‘to consolidate’ in the translation above:

✴is also used in these recensions for the biographical note given to Etana (perhaps because he was believed to have established dynastic succession - see above); and

✴is implicit (in its Old Akkadian form) in the name of Sargon, Sharrum-kīn, which literally means ‘the king is permanent’.

Interestingly (as discussed in more detail in the following page, which discusses the putative Sargonic recension of the SKL), Ur-Zababa:

✴appears again in the SKL, when (the presumably young) Sargon is described as his cupbearer; and

✴in Sumerian literary tradition, where he is a contemporary of both Sargon and King Lugalzagesi of Uruk.

Thus, Ku-babu’s dynasty seems to have ruled Kish:

✴from the end of the reign of Ibbi-Sin (= Enbi-Istar ?], who might be synchronised with Enshakushana (see above); and

✴until the time of Lugalzagesi and Sargon.

USKL Kings Nanne and Meshnune and SKL King Nannya

As mentioned above, Nanne, the penultimate Kishite king in the USKL, can arguably be equated with Nanniya, the last Kishite king named in the SKL (at line 254), where an added narrative note identifies him as a stone cutter. The case of Meshnune, the son of Nanne the the USKL is more surprising, since:

✴no Kishite king of this name appears in the SKL; and

✴he is the only Kishite king other than Akka (the son of Emebaragesi - see above) who is given a patronymic in the USKL.

It is ths entirely possible that the only thing that Shulgi’s scribe knew (or thought he knew) about Meshune was that he was the son of a Kishite king named Nanne.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 278) pointed out that a pair of similar ‘father and son’ names appears in the SKL in two dynasties of Ur:

✴Ur I: Mesanepada (SKL 135) and Meskiagnuna, son of Mesanepada (SKL 137-8); and

✴Ur II: Nanni (SKL 194) and Meskiag-Nanna, son of Nanni (SKL 196).

Interestingly, two relevant royal inscriptions that mention Mesanepada survive:

✴a bead found at Mari names Mesanepada as king of Ur and the son of Mes-kalam-du, king of Kish (RIME 1: 13: 5: 1); and

✴a clay sealing from Ur names Mesanepada himself as king of Kish (RIME 1: 13: 5: 2).

The point here is that, by the time of the historical Mesanepada, the title ‘king of Kish’ seems to have become an honorific title, with the connotation ‘king of the world’, probably indicating hegemony (or at least the claim of hegemony) over the land of Sumer. This fact prompted Piotr Steinkeller (as above) to ask, rhetorically:

“Is it possible that [the USKL kings] Nanne and Meshnune are in fact Mesanepada and Meskiagnuna of Ur, whom the USKL classified as Kishite rulers because Mesanepada held the title of [king of Kish]? If so, [their reclassification in the SKL as Ur I kings] would be fully justified.”

In other words, it is possible that the USKL scribe:

✴had epigraphical evidence for Mesanepada, king of Kish, and his son Meskiagnuna; and

✴abbreviated these two names as Nanne and Meshnune respectively and assumed that they had actually ruled at Kish.

This suggestion has been broadly accepted by (for example) Piotr Michalowski (referenced below, at pp. 159-60)) and Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming): its corollary would be that we should probably assume that Nannya found his way into the SKL because of this error.

Kishite Kings in the USKL: Conclusions

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 276) observed that:

“When viewed as a whole, the USKL differs most significantly from the SKL in its pre-Sargonic section.”

His point was that, in the SKL (as we have seen), this Kishite list was increased by about a third and split into three or four sub-sets, separated by intervening ‘dynasties’ that were associated with other (mostly Mesopotamian) cities, presumably reflecting the particular perspectives of the Isin kings. However, Shulgi’s scribe did not feel the need to interrupt his Kish A list, even to note the defeat suffered by Enmebaragesi and/or Akka at the hands of Shulgi’s hero Gilgamesh. Instead, he seems to have simply reproduced what was essentially a pre-existing list of Kishite kings (discussed below).

Putative Kishite Recension of the USKL

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 282) argued that no Sumerian ruler would have:

“... had any part in a project that assigns much of the past glory to Kish, ... This leaves us with only one possible agency [for the Kish A list in the USKL: Sargon [of Akkad and his successors, who would] have had an obvious interest in promoting the idea that Kish remained the seat of kingship from time immemorial down to Sargon’s own day. In such a scheme of history, Akkad became a natural heir and successor to Kish ...”

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023) further argued (at p. 244) that the Akkadians would have relied for this list on the Kishites’ own historiographical tradition, in which case:

“... the first recension of what would become the [USKL and subsequently the SKL would have been] written in Kish before ca. 2350 BC.”

If so, then Shulgi’s scribe would essentially have relied on the ‘Kishite recension’, as mediated by Sargon (as discussed in the following page), restricting his own input to:

✴the addition of the filiation of Akka in column 2; and

✴the erroneous addition of Nanne and his son Meshnune to the end of the list.

References

Gabriel, G. I.,"The ‘Prehistory’ of the Sumerian King List and Its Narrative Residue", in:

Konstantopoulos G. and Helle S., “The Shape of Stories”, (2023) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 234-57

Gabriel, G. I.,"Von Adlerflügen und Numinosen Insignien: Eine Analyse von Mythen zum Himmlischen Ursprung Politischer Herrschaft nach Sumerischen und Akkadischen Quellen aus drei Jahrtausenden", in:

Gabriel, G. I. et al., (editors), ”Was vom Himmel kommt: Stoffanalytische Zugänge zu Antiken Mythen aus Mesopotamien, Ägypten, Griechenland und Rom”, (2021) Berlin, Munichand Boston, at pp. 309-407

Sommerfeld W., “Old Akkadian”, in:

Vita J.-P., (editor), “History of the Akkadian Language”, (2021) Boston and Leiden, at pp. 513-663

George A. R., “The Tamarisk, the Date-Palm and the King: A Study of the Prologues of the Oldest Akkadian Disputation", in:

Jimenez E. and Mittermayer C. (editors), “Disputation Literature in the Near East and Beyond”, (2020) Berlin and Boston, at pp. 75-90

Westenholz A., “Was Kish the Center of a Territorial State in the Third Millennium?—and Other Thorny Questions”, in:

Arkhipov I. et al. (editors), “The Third Millennium: Studies in Early Mesopotamia and Syria in Honor of Walter Sommerfeld and Manfred Krebernik”, (2020) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 686-715

George, A. R., “Sumero-Babylonian King Lists and Date Lists”, in

George, A. R. (editor), “Cuneiform Royal Inscriptions and Related Texts in the Schøyen Collection”, (2011) Bethesda, Md, at pp. 199-209

Marchesi G., “The Sumerian King List and the Early History of Mesopotamia”, in:

Biga M. G. and Liverani M. (editors.), “Ana Turri Gimilli: Studi Dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer da Amici e Allievi”, (2010) Rome, at pp 231-48

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Vol. 1: Presargonic Period (2700-2350 BC)”, (2008) Toronto

Klein J., “The Brockmon Collection Duplicate of the Sumerian King List (BT 14)”, in:

Michalowski P. (editor), “On the Third Dynasty of Ur: Studies in Honor of Marcel Sigrist”, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Supplemental Series 1, (2008) at pp. 77–9

Michalowski P., “The Strange History of Tumal", in”

Michalowski P. and Veldhuis N. (editors), “Approaches to Sumerian Literature: Studies in Honour of Stip (H. L. J. Vanstiphout)”, (2006) , Leiden, at pp. 145-66

Glassner J.-J., “Mesopotamian Chronicles’, (2004) Atlanta GA

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-92

Jacobsen T., “The Sumerian King List”, (1939) Chicago IL