Sumerian King List (SKL)

Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: USKL I: Putative Kishite King List (KKL)

Topic: USKL II: Putative Sargonic King List

Sumerian King List (SKL)

Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: USKL I: Putative Kishite King List (KKL)

Topic: USKL II: Putative Sargonic King List

Putative Sargonic King List and the USKL

text

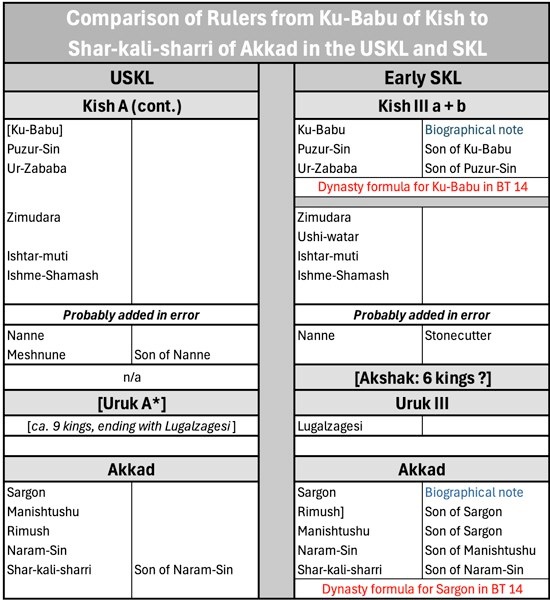

Rulers from Ku-Babu to Shar-kali-sharri in the SKL and the USKL

Table 8

As noted in Table 8:

✴in the earliest recensions of the SKL:

•two familial dynasties ruled in this period:

-the Kish III a+b dynasty, founded by Ku-Babu; and

-the dynasty of Akkad, founded by Sargon; and

•each of Ku-Babu and Sargon was given a biographical note; and

✴in one of them (BT 14 = number 3), each of Ku-Babu and Sargon was given a ‘dynasty formula’.

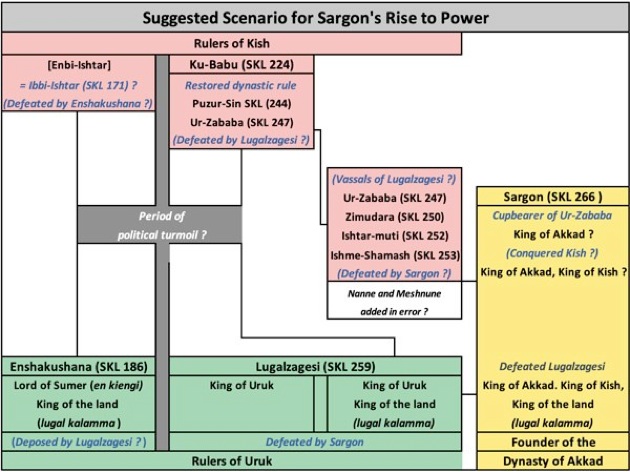

As noted above, the biographical note attached to King Sargon of Akkad indicates that he was a contemporary of Ur-Zababa. Furthermore, Ur-Zababa, and Sargon appear as contemporaries of Lugalzagesi in the Sumerian literary tradition. This might explain why (as discussed above) the Akshak dynasty was subsequently moved up the SKL list, thereby separating Ku-Babu from her direct descendants: this ‘modification’ brought Ur-Zababa closer to Sargon and Lugalzagesi. (Perhaps she was left behind because there was a tradition that linked her chronologically to the kings of Mari, the preceding city dynasty.)

Some scholars argue that the assertion in Sargon’s biographical note that Sargon had served at the court of Ur- Zababa cannot have been based on historical fact: for example, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p. 183) argued that this assertion:

“... is invalidated by the SKL’s own evidence, ... [which names] five (or six) additional kings of Kish following Ur-Zababa. This evidence precludes any possibility that Sargon could have served Ur-Zababa before his [Sargon’s] ascent to the throne of Akkad.”

However, in my view, we cannot discount the testimony of the biographical note so easily, since:

✴as discussed on the previous page, King Nanne of Kish probably found his way into the SKL following his inclusion in error in the USKL and should therefore be ignored in this context; and

✴if a compiler of the SKL had decided to invent a ‘tradition’ in which Sargon served as cupbearer to a Kishite king, it is hard to see why he would have chosen Ur-Zababa to be the king in question, given the fact that he could just as easily have chosen a later king in his list.

This raises an obvious question: if the traditional synchronism between Sargon and Ur-Zababa (Ku-Babu’s grandson) was not invented by the earliest compiler of the SKL, where did it originate? It was certainly not in the USKL, where Ur-Zababa and Sargon are separated by:

✴probably three kings of Kish (putting Nanne and Meshnune to one side); and

✴about 9 other kings (all of whom probably ruled from Uruk).

As discussed above, Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 244) argued that the list of Kishite kings in the USKL must have been compiled from the Kishites’ own historiographical tradition.

This follows from the assertion by Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 282) that no Sumerian ruler would have:

“... had any part in a project that assigns much of the past glory to Kish, ... This leaves us with only one possible agency [for the Kish A list in the USKL: Sargon [of Akkad and his successors, who would] have had an obvious interest in promoting the idea that Kish remained the seat of kingship from time immemorial down to Sargon’s own day. In such a scheme of history, Akkad became a natural heir and successor to Kish ...”

He elaborated on this in a later paper (Steinkeller, referenced below, 2019, at p. 40), where he argued that the precursor of the USKL:

“... probably was written down in Sargonic times, with an express objective of demonstrating that, save for a brief interlude involving Lugalzagesi and perhaps some other kings of Uruk, the Sargonic dynasty was a continuation of the kingdom of Kish. In other words, this hypothetical [Sargonic king] list was, in its essence, a linear history of the northern Babylonian monarchy. If so, this ‘history’ would have been part of the ideological innovations that the Sargonic kings introduced to foster the idea of a unified Babylonian state, thus radically differing from the traditional, Sumerian types of historical records.”

He also summarised (at p. 122) how Sargon was able to unify ‘Babylonia’:

“After he had conquered northern Babylonia together with its traditional political centre, Kish, Sargon then confronted Lugalzagesi. In the ensuing war, Sargon faced and overcame a formidable coalition of southern city-states led by Lugalzagesi, after which he [also] became the master of the South ...”

There is no mention here of Akkad. However, I suggest that:

✴Ur-Zababa and the other three kings of Kish who followed him in the USKL held their titles as vassals of Lugalzagesi (as is suggested the literary tradition - see, for example, Nshan Kesecker, referenced below, at p. 87); and

✴when Sargon conquered Kish from the last of them, Ishme-Shamash, he had already assumed the title of king of Akkad.

Thus, the putative Sargonic precursor of the USKL might well have been written (in Akkadian) after Sargon’s conquest of Kish, for the benefit of his new subjects, and it need not have made any reference to Lugalzagesi or, indeed, to any ruler of Uruk: kingship had resided at Kish throughout the period from Gushur to Ishme-Shamash, when Sargon:

“... conquered the city of Kish and destroyed its walls. He was [victorious] over Kish in battle, [conquered the city]”, (wording adapted from a royal inscription in which Sargon recorded his subsequent capture of Uruk from Lugalzagesi, translated by Douglas Frayne, 1993, entry E2. 1. 1. 1, at p 10).

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at pp. 247-8), in this putative Sargonic pre-cursor of the USKL:

“The Sargonic rulers [introduced] the concept of a change of hegemony to the SKL. In this version of events, the gods did not bequeath kingship to Kish forever: they later passed it on to other worthy cities. This change results in the altered semantics of the identical initial copular phrase (kishki lugal-am3):

✴from an eternal truth, ‘Kish has (always) been king’; to

✴a delimited segment of history, ‘Kish was king’.

To convey the concept of change, the Akkadian redactors supplemented the vertical transfer of kingship from heaven to earth with a horizontal transfer of kingship from city to city.

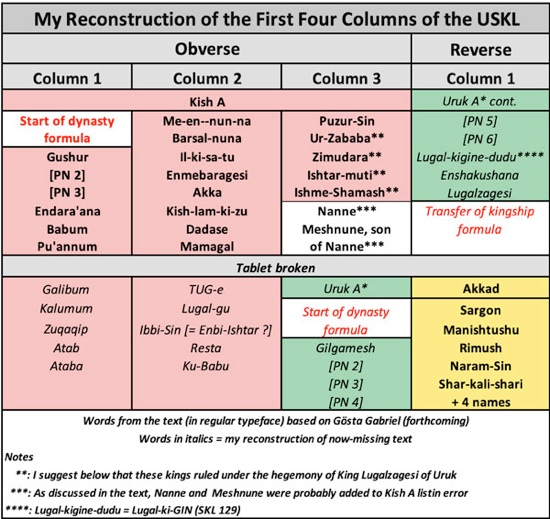

The table above summarises the likely contents of the first part of earliest known recension Sumerian King List (SKL), which was compiled in the reign of the Ur III king Shulgi (and known as the USKL). In fact, the USKL text is known from only a single tablet that was first published by Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003), and this tablet (in its present state) preserves only part (50-60 %) of the original text. The table above summarises the text in the first four (of the six) original colums:

✴the text in regular type summarises the surviving text; and

✴the text in italics summarises my suggested completion.

The text began with about 30 kings of Kish: as I discussed in the previous page (USKL I: Kishite Recension), Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023 at p. 244) argued that this list (which he dubbed the ‘Kish A’ list) was compiled from the Kishites’ own historiographical tradition, in which case:

“... the first recension of what would become the [USKL and subsequently the SKL would have been] written in Kish before ca. 2350 BC.”

He also agreed with Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 282), who reasonably argued that:

“... it is inconceivable that Shulgi ... had any part in a project that assigns much of the past glory to Kish ... [In fact, there is on] one possible agency for whom the USKL’s version of history would have been an acceptable one:the dynasty of Akkad. Sargon and his successors would, in fact, have had an obvious interest in promoting the idea that Kish had remained the seat of kingship from time immemorial down to Sargon’s own day. In such a scheme of history, Akkad became a natural heir and successor to Kish ...”

In this scenario:

✴Sargon and/or his successors would have extended an earlier ‘canonical’ list of Kishite kings into an ‘updated’ king list that was designed to demonstrate that they were the natural heirs of the ancient kings of Kish; and

✴Shulgi’s scribe would subsequently have incorporated this list into the early part of what we now refer to as the USKL.

In what follows, I will attempt to set out the circumstances in which this putative Sargonic recension of the USKL might have been commissioned and what it might have looked like, beginning by working backwards from the USKL text.

Sargon in the USKL

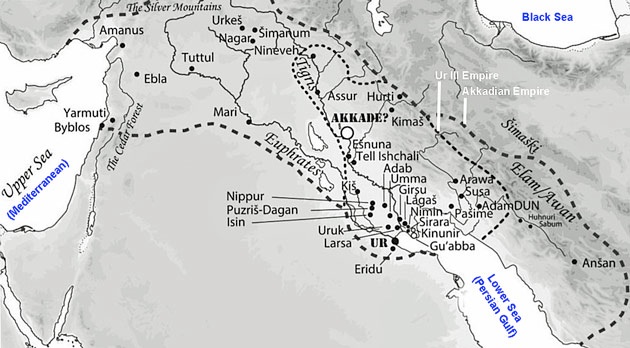

Maximum Extent of the Akkadian and the Ur III Empires

Image adapted from Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2021, Map 2.1, at p. 69)

My additions: text in white and blue

As is indicated by the map above, at its height, the ‘Akkadian’ empire that Sargon founded was of impressive extent (probably even greater than that ever achieved by Ur-Namma, Shulgi and their ‘Ur III’ successors). Thus, by Shulgi’s time, Sargon’s accession to the throne of Akkad would have been seen as a defining moment in Mesopotamian history. Yet Sargon appears only once in the surviving USKL text: as indicated in the table at the top of the page, the first line following the lacuna that almost certainly contained the names of about 9 early kings of Uruk (the Uruk A* list), recorded that:

“Sargon, in Akkad, ruled for [x] years”.

Thus, we do not know how Sargon was introduced in the preceding (now-lost) text.

What we do know is that Sargon’s first major victory in southern Mesopotamia was over King Lugalzagesi of Uruk, which makes it almost certain that the last lines in the preceding lacuna contained the formulae that described the transfer of kingship from Lugalzagesi of Uruk to Sargon of Akkad. Only one set of such formulae involving the transfer between two Mesopotamian rulers is found on the tablet as it now survives (at reverse, column 3, lines 15’-22’):

In Uruk, Utu-hegal ruled for [x] years

Uruk was struck with weapons

The kingship was carried away to Ur

In Ur, Ur-Namma ruled for [x] years

It is possible that, in the present case, the same formulae were used, with:

Lugalzagesi instead of Utu-hegal; and

Sargon (at Akkad) instead of Ur-Namma (at Ur).

However, it seems to me that, given the seismic importance of Sargon’s victory over Lugalzagesi, it is unlikely that he appeared in the USKL ‘out of nowhere’, simply as the king of Akkad who took over the kingship of King Lugalzagesi of Uruk.

Sargon’s Rise to Power

Unfortunately, our sources for Sargon’s early career are extremely poor, to the extent that even the location of Akkad has yet to be determined (although it is generally agreed that it was on the Tigris, near its confluence with the Diyala river - see the map above). Interestingly, one of the most important (although not necessarily one of the most reliable) surviving sources for this early period is in the biographical note given to Sargon in the SKL, where we read that:

“Sargon, whose father was a gardener, the cupbearer of (king) Ur-Zababa, (thereafter) the king of Akkad, the one who built Akkad, was king [there]”, (SKL 266-271).

Fortunately, our surviving sources for the political situation in Uruk at this time are rather better, and I will therefore start by:

✴revisiting what we know about the last pre-Sargonic rulers of Uruk; and then

✴considering how their political and military successes and failures might have affected the contemporary rulers at Kish and Akkad.

King Enshakushana of Uruk (SKL 186)

One of the few things that we know for certain about Sargon’s early career is that he was closely associated with Akkad. Interestingly, as Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 93) pointed out, an administrative document at Nippur was dated to the:

“year in which Enshakushana defeated Akkad.”

They argued (presumably of the basis of the SKL note) that:

“Before Sargon, Akkad was not known as a city, so this [year name] can be taken as the first indirect proof for the existence of Sargon as a contemporary of Enshakushana. Although this document does not bear a direct reference to king Sargon, prosopography demonstrates that Sargon must have ruled at Nippur not too many years later. This fact supports the impression that the reference to Akkad in the Enshakushana year date, in fact, points to a mighty ruler there, namely Sargon.”

However, as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, note 487, at p. 190) pointed out:

“Correctly, all that this evidence proves is the existence of Akkad at the time of Enshakushana. While it does not exclude the possibility that Sargon ruled over Akkad at that time, it in no way demonstrates it.”

In the body of the text, he argued that, on the contrary:

“As far as one can ascertain, Akkad existed as a town or city before Sargon., ... [as] demonstrated quite securely by a date-formula of Enshakushana of Uruk (Lugalzagesi’s predecessor), who was involved in a conflict with Akkad.”

In other words, (as I argue below), it is also possible that Sargon liberated Akkad from the hegemony of Enshakushana and then rebuilt the city as his capital.

Interestingly:

✴another of Enshakushana’s year-names at Nippur was ‘the year in which he besieged Kish’: and

✴the ‘Ekur bowls’ that he dedicated there recorded that:

“Enshakushana, lord of Sumer (en kiengi) and king of the land (lugal kalamma), destroyed Kish and captured Enbi-Ishtar, the king of Kish. ... [Kish was] destroyed ... [Enshakusana] dedicated [the spoils that he took from Kish] ... to [the god] Enlil at Nippur” (RIME 1: 14: 17: 1; CDLI P431228).

As far as we know, Enshakushana did not use the title ‘king of Kish’, perhaps because this title (which had apparently been a prestigious ‘badge of honour’ in the previous period) was now subsumed by the title lord of Sumer and king of the land.

Ibbi-Sin (SKL 171) = Enbi-Ishtar of Kish?

As noted on the previous page, it is possible that the name ‘Ibbi-Sin’ (who is recorded at SKL 171 as the last Kish II) might have represented a mis-reading of ‘Enbi-Ishtar’ in the USKL. Interestingly:

Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below at p. 169) completed SKL 171 (which was corrupt in the exemplars at his disposal) as Enbi-Ishtar on the basis of this inscription of Enshakushana;

Jean-Jacques Glassner (referenced below, at pp, 122-3) completed it as Enbi-[Ishtar]; and

Douglas Frayne (referenced below, at p. 52) completed it as Ibbi-[Ishtar(?)].

Thus, as discussed in my page on the ‘Utu-hegal recension’, it is possible Enshakushana of Uruk and Enbi-Ishtar of Kish both appeared in the USKL, which (again) raises the question of how their synchronisation would have been handled.

King Lugalzagesi of Uruk (SKL 259)

As Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 87) observed, Lugalzagesi, the erstwhile ensi of Umma:

“... succeeded Enshakushana as king of Uruk, and inherited the latter’s state, which also included Nippur. ... This rise of Lugalzagesi to become overlord of Babylonia is reflected in a year name from Nippur:

‘[The year in which] Lugalzagesi assumed the kingship’.”

It seems likely that this year coincided with the year in which Lugalzagesi’s ‘Ekur bowls’ were dedicated at Nippur: the inscription on them began:

“[To] Enlil, king of all lands (lugal kurkurra):

For Lugalzagesi, king of Uruk, king of the lands (lugal kalamma), ishib priest of An, lumah priest of Nisaba, son of Bubu, the ensi of Umma, lumah priest of Nisaba ...

When Enlil, the king of all lands, gave to Lugalzagesi the kingship of the land (nam-lugal-kalamma), ... [Enlil]:

✴made [the lands] ... submit to him, from east to west; [and]

✴made the roads passable for him from the Lower Sea, along the Tigris and the Euphrates, to the Upper Sea.

When Enlil made him a man without rival from east to west, all the lands rested contentedly ... ”, (RIME 1: 14: 20: 1: CDLI P431232, see also the translation by Gàbor Zólyomi, referenced below).

There is no reason to think that this inscription presents a particularly exaggerated picture of the extent of of Lugalzagesi’s hegemony: after all (as we shall see) , a single victory over him effectively gave Sargon control of the whole of Sumer.

King Ur-Zababa of Kish

As noted above, the biographical note that is attached to Sargon in the SKL records that, presumably early in his career, he served as the cup-bearer at the court of Ur-Zababa. It is generally accepted that the records of:

✴the Kishite king Ur-Zababa named at obverse column 3 in the USKL (who is names as son of Puzur-Sin at SKL 247); and

✴the Ur-Zababa whom Sargon had served as cupbearer, according to the biographical note at SKL 268;

refer to the same Kishite king. However, as I noted above, the historical accuracy of the biographical note is open to question: for example, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p. 183 and note 468) argued that:

“... the proposition that Sargon was a cup-bearer of Ur-Zababa is invalidated ... [by] the fact that ... [the SKL names six and the USKL names five] additional kings of Kish following Ur-Zababa. This evidence precludes any possibility that Sargon could have served Ur-Zababa before his ascent to the throne of Akkad.”

However, in my view, we cannot discount the testimony of the biographical note so easily, since:

✴as discussed on the previous page, Shulgi’s scribe had probably added Nanne and his son Meshnune to the Kish A list in USKL in error, so they should be ignored in this context; and

✴it is at least possible that Ur-Zababa and the other three kings of Kish who followed him held their titles as vassals of Lugalzagesi (as discussed below).

Furthermore, if a compiler of the SKL had decided to invent a ‘tradition’ in which Sargon served as cupbearer to a Kishite king, it is hard to see why he would have chosen Ur-Zababa to be the king in question, given the fact that he could just as easily have chosen a later king in his list.

Interestingly, as Piotr Steinkeller (as above, at p. 182) pointed out, Sargon is also described as the cup-bearer of Ur-Zababa in the so-called ‘Sumerian Sargon Legend’, which is known from two surviving fragmentary tablets (one from Uruk and the other from Nippur) that were published in 1983 by Jerrold Cooper and Wolfgang Heimpel (referenced below: see also the on-line translation by ETCSL). As these authors noted, this text survives in three segments (labelled as segments A-C in ETCSL):

✴‘segment A’ (on the obverse of the Uruk fragment) contains the beginning of the surviving text;

✴‘segment B’ (on the Nippur fragment) contains the central part of the legend; and

✴‘segment C’ (on the reverse of the Uruk fragment) contains all that we know about its ending.

In this account, Sargon, who is introduced as Ur-Zababa’s cup-bearer in segment B (at line 12), inadvertently becomes the subject of Ur-Zababa’s paranoid conviction that the gods have already chosen him (Sargon) as his successor. After an unsuccessful attempt to murder Sargon at Kish:

“King Ur-Zababa despatched Sargon, the creature of the gods, to Lugalzagesi in Uruk with a message written on clay, which was about murdering Sargon”, (B: 55-6).

Although, in the text (as it now survives), the relationship between Ur-Zababa and Lugalzagesi is not explicitly defined, the nature of the interactions between them arguably suggests that Ur-Zababa was Lugalzagesi’s vassal (see, for example, Nshan Kesecker, referenced below, at p. 87). It is worth reproducing Segment C here, in order to illustrate how little we know about the events that (allegedly) followed:

“With the wife of Lugalzagesi ... She (?) ... her femininity as a shield. Lugalzagesi would not (reply) the envoy, (and said):

‘Come now! Would he step within E-ana’s (walls)’.

Lugalzagesi did not understand, so he did not talk to the envoy. (But), as soon as he did talk to the envoy, the eyes of the prince’s son were opened. The lord (sighed) and sat in the dirt. Lugalzagesi replied to the envoy:

‘Envoy, Sargon does not yield.’

When he submits, Sargon ...”, (see Cooper and Heimpel, referenced below, at p. 77).

Cooper and Heimpel observed (at p. 68) that, in this segment:

“Lugalzagesi is questioning a messenger (presumably Ur-Zababa's from Kish) about Sargon's refusal to submit to Lugalzagesi:

✴If the composition ends with that column, there is scarcely room enough to give the messenger's response and then very summarily to relate events back in Kish and Sargon's triumph.

✴If, however, this tablet is only the first half of the composition, the second tablet would [presumably have recounted] the foretold death of Ur-Zababa, the succession of Sargon, and the battle in which Sargon finally defeated Lugalzagesi and established his hegemony over all of [Mesopotamia].”

However, this possible end to the legend is a matter of pure speculation: all we know for certain is that, in segment C:

✴Sargon refused to submit to someone (Lugalzages ? Ur-Zababa ?); and

✴whatever happened next, he survived the envoy’s visit to Lugalzagesi’s court.

For our purposes, the key question is whether this legend:

✴actually reflects the political situation in Kish and Uruk in the pre-Sargonic period; or

✴was an invention of the scholars at the isin court.

Jerrold Cooper and Wolfgang Heimpel (referenced below, at p. 68) observed that the surviving text:

“... is full of grammatical and syntactic peculiarities that suggest a later Old Babylonian origin. ... But, this may just be a degenerate version of a text composed in the Ur III period; only the future discovery of more literary texts from that period and from other sites will enable us to know for certain.”

In other words, we cannot rule out the possibility that an earlier version of this tradition was available to Shulgi’s scribe, in which case it would presumably influenced the structure of the USKL (even it was not overtly referred to in its text).

This brings us back to the problem of the status of the three Kishite kings who followed Ur-Zababa in the USKL. As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at pp. 183-4 and note 469) pointed out, it is likely that, under Sargon, Kish was administered by an Akkadian governor (rather than by a nominal king):

✴Sargon recorded in his own royal inscriptions (see, for example, RIME 2: 1: 1: 2, CDLI: P461927, lines 82-91) that, throughout his territories (which included Kish), he appointed sons (i.e., citizens) of Akkad as his ensi (regional governors); and

✴Naram-Sin (Sargon’s grandson), in his inscriptions recording his suppression of the ‘Great Rebellion’ (see below), routinely referred to the fact that the rebel cities had elevated their respective leaders to the kingship at the start of their respective rebellions (see, for example, RIME 2: 1: 4: 6, CDLI: P461982, lines 11’-13’ for the case of Iphur-Kish, the rebel king of Kish).

However, this does not preclude the possibility that, in the immediately prior period, Ur-Zababa and the three kings who followed him all ruled Kish as vassal kings of Lugalzagesi.

Sargon’s Conquest of Kish

As we shall see, there is no doubt that:

✴at some point in his career, Sargon conquered Kish; and

✴from at least the time of his victory over Lugalzagesi, he used the title ‘king of Kish’.

However, in order to assess how this conquest might have been reflected in the USKL and preceding putative Sargonic recension, we need to establish whether it occurred before or after Sargon’s victory over Lugalzagesi. Unfortunately (as we shall see), the relevant surviving evidence does not enable a clear decision on this point.

Evidence of the ‘Legend of the Great Revolt against Naram-Sin’

The only surviving narrative account of Sargon’s conquest of Kish comes in an Old Babylonian copy from Mari of part of the so-called ‘Legend of the Great Revolt against Naram-Sin’ (discussed and translated by Joan Goodnick Westenholz, referenced below, as entry 16a, at pp. 231-7). This text included a complaint allegedly made by Naram-Sin about the ingratitude of the Kishites when they joined this widespread rebellion against his hegemony:

“... after my (grand)father Sargon conquered the city of Uruk, he established freedom for the Kishite (people): he had their slave marks shaved off and their shackles removed: he escorted Lugalzagesi, their despoiler, to Akkad. And (yet), ... they rebelled against me, [his grandson. ... They] assembled and raised Iphur-Kish, the man of Kish, son of Summirat-Ishtar (the lamentation priestess), to kingship”, (lines 5-9).

According to Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p. 171, citing Claus Wilcke, referenced below, note at p 30 on lines ix 32 - x14), although this text belongs to an Old Babylonian version of the legend:

“... the passage [therein] describing how Sargon ... wrested Kish from Lugalzagesi’s control was part of the Old Akkadian original.”

Thus, this passage might well have been composed during or shortly after the reign of Naram-Sin, certainly suggests that Sargon’s ‘liberation’ (aka his conquest) of Kish took place immediately after his victory over Lugalzagesi.

Evidence of an Administrative Document from Ebla

Stephanie Dalley (referenced below, at p. 28) pointed out that, at around the time of Sargon’s rise to power:

“... evidence from administrative texts found at Ebla, [a city on the upper reaches of the Euphrates], shows that Kish was the most important city of northern Mesopotamia, maintaining its prestige despite a defeat ... [probably inflicted in the campaign led by] Enshakushana of Uruk against Enbi-Istar, king of Kish. ... A victory over [nearby] Mari in which Kish was an ally [of Ebla] a few years later ... was followed by the dynastic marriage of the Eblaite princess Keshdut to the [unnamed] king of Kish. Ebla was ‘destroyed’ not long afterwards ...”

Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 98) discussed a number of documents found at Ebla that refer to the gifts that were distributed by the court on the occasion of this marriage (which were published in the same volume by Alfonso Archi, at pp. 178-9). They argued that:

“This [unnamed Kishite] ruler can be identified only with Sargon of Akkad, [assuming that] one applies the here-established synchronisms of the late Pre-sargonic period.”

They also pointed out that the gifts were made not only to the Kishite king himself but also to his father, a practice that was otherwise unknown in:

“... the enormous documentation of royal gifts known from the palace of Ebla”

They further argued that:

“The unique reference [here] to a ‘father’ of the ‘king of Kish’ ... exactly fits the situation of the newcomer Sargon, whose main royal title was ‘king of Kish’ and who never appears (in either his own inscriptions or in the Mesopotamian tradition) as the successor of a preceding ruler ...”

It seems to me that, in this particular context, a dynastic marriage between a princess of Ebla and a man described as ‘king of Kish’ would have implied that the man in question was, first and foremost, the actual king of the city of Kish. In other words, I suggest that, assuming that Keshdut’s bridegroom can indeed be identified as Sargon, then this marriage must have taken place after he had conquered Kish but before his victory over Lugalzagesi (at which point, he would have had even grander titles - see below).

Evidence of Sargon’s Royal Inscriptions

The only surviving and unequivocally contemporary evidence for Sargon as king of Kish comes from his own royal inscriptions: as Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993, at p. 3) observed:

“The Sargonic period marks the first time the Akkadian language was extensively used for royal inscriptions [in Sumer]. The majority of inscriptions [from this time] are recorded in that language, [although] a minority are known in bilingual (Sumerian and Akkadian) versions, and a handful are in Sumerian alone.”

He also pointed out (at p. 7) that, although very few of these inscriptions survive in their original form:

“... a sizeable number [of them are] known from later Old Babylonian tablet copies: [in particular], two large Sammeltafeln [compilations of such copies] from Nippur:

✴one, [now] in Philadelphia (CBS 13972); [and]

✴the other, [now] in Istanbul (Ni 3200);

contain copies of several Sargon inscriptions. ... The originals of these copies may have been inscribed on triumphal steles that once stood in the courtyard of Enlil's Ekur temple in Nippur.”

In this context, he argued (again at p. 7) that (as noted above):

“Although the evidence of the ‘Sumerian Sargon Legend’ ... suggests that the fall of Kish was brought about as a result of the defeat of Ur-Zababa by Sargon, it is noteworthy that fully five Kishite royal names follow Ur-Zababa in the Sumerian King List [as discussed above]. ... Presumably as a consequence of his [eventual] defeat of Kish, Sargon adopted the title lugal Kish, which, in the context of the Sargonic royal inscriptions, should be translated as ‘king of the world’.”

In the analysis below, I will argue that, although the title ‘king of Kish’ came to mean ‘king of the world’ at some time during Sargon’s reign (and was used in the same way thereafter by both of his sons when they, in turn, succeeded him), it had the more obvious meaning of king of the city of Kish at the time of Sargon’s early conquests of Sumer, Mari and Elam.

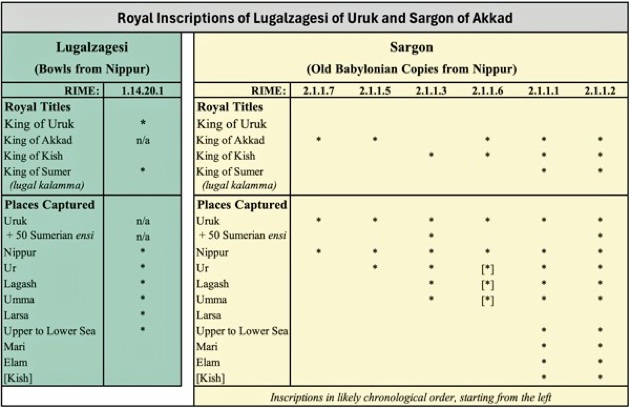

The evidence for my conclusion is laid outed in the table above, in which I have summarised the contents of the six earliest of Sargon;s surviving inscriptions, all of which are known from the Nippur Sammeltafeln: I have arranged them in the order suggested by the number of major conquests to which they refer (in the hope that this roughly corresponds to their chronological order):

✴all of them record his conquest of Uruk, and I have assumed that he also controlled Nippur at this time since:

•all of the originals came from Nipur; and

•the last three recorded dedications that Sargon made there immediately after his conquest of Uruk;

✴an intermediate pair also record his conquests of the Sumerian cities of Ur, Lagash, Umma and Larsa; and

✴the last pair (one of which, RIME 2: 1: 1: 21, is bilingual):

•also record his conquests over a much wider area, including Mari and Elam; and

•indicate that, at this time, he also controlled Kish (see below).

Interestingly, Sargon used the title:

✴king of Akkad in five of the six inscriptions;

✴king of Kish in the last four of them; and

✴king of Sumer (lugal kalamma) in the last two.

However, in all of his subsequent surviving inscriptions in which a title is used, this title is always and exclusively ‘king of Kish’ (as mentioned above).

It seems to me that there are two important points to be made here:

✴First, Sargon did not record his actual conquest of Kish in any of these six ‘early’ inscriptions, albeit that, in the last two, we read that, having conquered Lugalzagesi, he:

“... altered the two sites of Kish [and] made the two (parts of Kish) occupy (one) city”, (RIME 2: 1: 1: 2, CDLI P461927, lines 100-8);

which presumably refers to his amalgamation of the previously twin cities of Kish itself and nearby Hursagkalama. This suggests that he had already conquered Kish (and possibly developed it as a second dynastic capital, alongside Akkad) before his victory over Lugalzagesi.

✴Secondly, in these last two inscriptions, he used the three titles king of Akkad, king of Kish and king of Sumer while, thereafter, he used only the title lugal Kish, presumably denoting ‘king of the world’. In my view, this indicates that:

•the three titles that used in some or all of the six early inscriptions indicated his rule over the city of Akkad, the city of Kish and the territory of Sumer; and

•thereafter, he adopted a single title, ‘king of Kish’ (tout court), denoting the fact that he was now ‘king of the world’.

Sargon’s Conquest of Kish: Conclusions

I must first acknowledge that, given the state of our surviving evidence, it is impossible to establish with any degree of certainty how Sargon’s conquest of Kish fitted into his early career . However, I would argue that the most likely scenario (notwithstanding the evidence of the ‘Legend of the Great Revolt against Naram-Sin’) is that he conquered Kish before his victory over Lugalzagesi. I therefore suggest that the scenario that was probably celebrated in the putative Sargonic recension of the USKL was one in which Sargon:

✴established himself as king of Akkad at about the same time as Lugalzagesi replaced Enshakushana as king of Uruk;

✴‘liberated’ Kish from Lugalzagesi’s hegemony thereafter, at which time he assumed the additional title of king of (the city of) Kish:

✴subsequently defeated Lugalzagesi himself and his Sumerian allies, after which he became king of Akkad, king of (the city of) Kish and king of Sumer; and

✴shortly thereafter, having defeated Mari and Elam, adopted the single title king of Kish, which indicated that he was now ‘king of the world’.

Sargon’s Early Career: Conclusions

p

Steinkeller made an important subsidiary point:

“Sargon and his [Akkadian successors] would ... have had an obvious interest in promoting the idea that Kish [had] remained the seat of kingship from time immemorial down to Sargon’s own day. In such a scheme of history, Akkad became a natural heir and successor to Kish, with the brief period of Urukean domination from Enshakushana down to Lugalzagesi representing [only] an aberration from the normal state of affairs.”

He returned to this hypothesis in a later paper (referenced below, 2019, at p. 40), and added another important observation: this putative ‘Sargonic’ king list was probably written:

“... with the express objective of demonstrating that, save for the [putative Urukean aberration], ... the Sargonic dynasty was a continuation of the kingdom of Kish. In other words, this hypothetical [Sargonic] list was, in its essence, a linear history of the northern [Mesopotamian] monarchy.”

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 244-5) similarly argued that the USKL must have been preceded by an Old Akkadian recension that included the ‘Kish A’ and ‘Uruk A*’ kings, to which the names of Sargon and his Akkadian successors were added. However, he also argued that:

“It is unlikely that the historical Old Akkadian rulers invented the long list of Kishite kings. It is much more probable that they copied an existing list of rulers and so continued the Kishite historiographical tradition (including the celestial origin of the city’s power and its extremely long first reign). Accordingly, the first recension of what would become the [putative Old Akkadian king list, then the USKL and then the SKL] was most likely written in Kish before ca. 2350 BC.”

text

Kings of Akkad in the USKL

The first surviving lines in on the USKL reverse begin with the first five kings of the dynasty of Akkad:

✴Sargon;

✴his sons, Manishtushu and Rimush;

✴his grandson, Naram-Sin; and

✴Shar-kali-shari, who is explicitly described as the ‘son of Naram-Sin’ .

In the SKL, Rimush ruled before Manishtushu (see, for example, Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, referenced below, in Table 5, at p. 18): although one might expect the USKL to be more accurate here than the later SKL recensions, evidence from a surviving inscription of Rimush favours the order of these kings as given in the SKL (see, for example, Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, at p. 14 and note 20).

The Gutians (a tribe from the Zagros Mountains that the Mesopotamians regarded as what the Greeks would later call ‘barbarians’) began causing trouble in Mesopotamia in the reign of Shar-kali-shari, as is evidenced by two of his year names (see Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 1993, at p. 183, entries k and n):

✴the year in which Shar-kali-shari:

•laid [the foundations] of the temple of the goddess Annunitum and of the temple of the god Ilaba in Babylon; and

•captured Sharlag, king of Gutium; and

✴the year in which Gutium was defeated.

As Nicholas Kraus (referenced below, at p. 7) observed, we know from the SKL that:

“... the leadership of Akkad fell into disarray after the death of Shar-kali-shari: in just three years, four kings are said to have ruled Akkad. That period of confusion was followed by the longer reigns of Dudu and his successor Sh-tural, [who reigned in succession for a period of 36 years, during which time they] strove to restore Akkad to its former glory. Those efforts are recorded in royal inscriptions and administrative records that reveal that:

✴Dudu defeated Umma and Girsu;

✴Akkad fought a battle against Uruk and Nagsu; and

✴Adab recognised Dudu and Shu-tural as sovereigns at some point during their reigns.”

The USKL similarly named four rulers in the period of confusion (although with no indication of the length of this period), and we might reasonably assume that the list continued (in what is now the lacuna of reverse column 2) with Dudu and Shu-tural.

Since the first name in the surviving part of reverse: column 2 is that of Kuda, the third Uruk IV king in the SKL, we might also reasonably assume that, in the original USKL, after the reign of Shu-tural:

✴kingship passed from Akkad to Uruk; and

✴the corresponding transfer of kingship formulae were followed by Ur-nigin and Ur-gigir (the first two Uruk IV king in the SKL) and Kuda.

According to the USKL, only after the reign of Kuda did kingship pass to the Gutians. The striking thing about this arrangement is that

Indeed, as discussed below, it is possible that at least one self-styled ‘king of Gutium’, Erridu-pizir, ex

Evidence of the Awan King List

Awan and Shimashki king lists from Susa,

now exhibit as Sb. 17729 in the Musée du Louvre (image from the museum website)

The Awan King List (AwKL) is known only from the Old Akkadian inscription illustrated above, which is on the obverse of what Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008a, at p. 38) characterised as:

“... a clay tablet from Susa that can be dated on the basis of its script to the period ca. 1800-1600 BC. The first part of the tablet gives a list of twelve personal names (without regnal years or genealogy) which are summarised by the rubric ‘twelve kings of Awan (LUGAL.MESH sha a-wa-anki)’”.

A similar list of twelve later kings of Shimashki is given on the reverse. In my view:

✴these two lists must have been copied from two separate documents (with the Shimashki list inspired by the older AwKL); and

✴the AwKL must have been commissioned by the redoubtable Puzur-Inshushinak, the twelfth and last king it records.

Although Puzur-Inshushinak is a securely historical figure, 10 of the 11 earlier AwKL kings are otherwise unknown. However, there is one other AwKL king whose reign can probably be dated: as Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 23) observed, the name of lu-uh-hi-ish-sha-an, the 8th king in the list, is almost certainly a variant spelling of the royal name Luhishan, which is found in a royal inscription of Sargon (RIME, 2: 1: 1: 8: P461933) that related to his conquest of Awan and Elam.

As we shall see, Puzur-Inshushinak can be synchronised with Ur-Namma, who recorded (inter alia) that he (Ur-Namma) had ‘liberated’ a number of territories in northern Mesopotamia, including ‘the land of Akkad’, from Puzur-Inshushinak’s control. Thus:

✴it is likely that the last five names in the AwKL belonged to historical kings of Awan who reigned in the period between Sargon and Ur-Namma; and

✴Puzur-Inshushinak might well have been inspired to compile the AwKL from king lists that he had seen in Akkad.

In other words:

✴the AwKL list of twelve kings, recorded without regnal years or patronymics, might well have been inspired by a much longer list of Kishite and Akkadian kings compiled in this way; and

✴this might well indicate the nature of the sources from Akkad that would have been available to Shulgi’s scribe when he compiled the USKL.

Evidence from Sargon’s Bilingual ‘Victory’ Inscription

Rather than start with the sources for the Kish A, Uruk A* and Akkad king lists, I would first like to address a more fundamental question: what was the origin of the ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae that characterise the USKL and (with a minor modification) all of the known SKL recensions. Interestingly, it is possible that the wording of Sargon’s bilingual ‘victory inscription’ (RIME 2: 1: 1: 1, CDLI: P461926) from Nippur might throw some light on this question.

Walter Sommerfeld (referenced below, at pp. 560-1) observed that, on the original monument:

“ ... a Sumerian translation [of the Old Akkadian text] was added in a separate place; both versions were then copied in parallel columns in the Old Babylonian Sammeltafeln [at Nippur] as a quasi-bilingual. The Sumerian version is a literal, in part awkward, translation of the Akkadian. But it is written, not in the Nippur dialect of Sumerian, but in the south Sumerian variety in which ... Lugalzagesi had also couched his inscriptions, even those deposited at Nippur in Enlil’s temple.”

One passage in this bilingual text is of particular relevance here:

✴in the Old Akkadian version, we read that Sargon had:

“... conquered the city of Uruk and destroyed its walls. He ... captured Lugalzagesi, king of Uruk, in battle and led him off to the gate of the god Enlil in a neck stock”, (column 2, lines 12-28); but

✴in the Sumerian version, the corresponding passage is given as follows:

“[Sargon] ... conquered the city of Uruk and destroyed its walls.

He struck the Man of Uruk with weapons and defeated him.

He struck Lugalzagesi, king of Uruk, with weapons and then seized him in a neck stock and carried him off to the gate of the god Enlil”, (column 1, lines 12-29).

Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993, at pp. 10-11) pointed to the same changes in wording between the Akkadian and the Sumerian versions at two other points in the text (see his notes on the Akkadian version at: lines 33-7, on the defeat of Ur; and lines 53-7, on the defeat of Umma). The point here is that the scholar who translated the Akkadian text chose to employ phraseology that was later used in the USKL:

✴as noted on many occasions above, the lines that would have described the transfer of kingship from Lugalzagesi to Sargon in the USKL is now lost; but

✴other USKL transfer formulae survive, including, for example, those describing the transfer from Utu-hegal of Uruk to Ur-Namma:

“In Uruk, Utu-hegal ruled for [x] years.

Uruk was struck with weapons.

The kingship was carried to Ur.

At Ur, Ur-Namma ruled for [x] years”, (reverse, column 3, lines 15’-22’).

It seems to me that:

✴in the Sumerian version of this bilingual inscription, Sargon’s scribe must have taken the wording in which Sargon ‘struck [an enemy king] with weapons’ from a Sumerian source; and

✴this source was probably one or more inscriptions in which Lugalzagesi (as ‘king’ of Umma ?) struck another king (Enshakushana ?) with weapons before taking his throne.

Some support for this hypothesis comes from the fact that Sargon consciously adopted some aspects of Lugalzagesi’s only known inscription (RIME 1: 14: 20: 1: CDLI P431232 - see above) for his own use at Nippur: for example:

✴as noted above, he used the south Sumerian dialect of Lugalzagesi in the Sumerian version of RIME 2: 1: 1: 1, CDLI: P461926; and

✴even in the Akkadian version (and in the Akkadian-only RIME 2: 1: 1: 2, CDLI: P461927) he claimed (like Lugalzagesi) that Enlil gave him no rival between the Upper Sea and the Lower Sea.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at pp. 10-11) observed that Lugalzagesi’s ‘Ekur; inscription:

“... may be classified as a historical text, ... [since] it deals with Lugalzagesi’s personal accomplishments. This is so [despite the fact that] it does not [describe] any specific historical events beyond a poetic description of the extent of Lugalzagesi’s political influence. ... This kind of rhetoric, which focuses on the figure of the king, represents a complete novum among Sumerian materials. When viewed from this perspective, the Lugalzagesi text clearly anticipates the voice of the Sargonic royal inscriptions.”

Given the (presumably intentional) non-violent character of this inscription, it is unsurprising that it shows no sign of the language of the later USKL ‘transfer of power’ formulae. Nevertheless, it is entirely possible that Lugalzagesi commissioned one or more other documents in which:

✴Gilgamesh ‘liberated’ Uruk from the hegemony of Kish by striking Enmebaragesi and/or Akka with weapons; and

✴Lugalzagesi, the ‘new Gilgamesh’, restored the liberty of Uruk by striking Enshakushana with weapons.

In other words, it is likely that Shulgi relied on purely Sumerian sources (perhaps mediated by Lugalzagesi) for the underlying phraseology of the ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae’.

Source for the Kish A and Uruk A* Kings in the USKL: Conclusions

In the sections above,

As noted on the previous page, Jasmina Osterman (referenced below, at p. 64) observed that:

“The first literary texts that became the basis of Mesopotamian literature (the Gilgamesh legends, creation epics, etc., the Sumerian king list and the first law code) date to [the Ur III period] and were written in the Sumerian language. ... [Gonzalo Rubio, also referenced below, at p. 169] has irrefutably demonstrated that Akkadian was the mother tongue of at least the second [Ur III] ruler, ... Shulgi, ... who carried out key reforms for the purpose of deifying the entire dynasty, [thereby] associating [its] rulers with the legendary, semi-divine, Sumerian king, Gilgamesh.”

She also observed that Jerold Cooper (referenced below, 2016, at p. 11):

“... has already established that, for now, there is no evidence for the existence of a distinct Sumerian identity until the time of Shulgi, when the Sumerian language (although it remained the official language of administration) was mostly only taught in schools and the spoken language was Akkadian.”

If we consider the USKL in the wider context of Shulgi’s apparent desire to revive the use of Sumerian (alongside the already prevalent Akkadian) among the élite and thereby create a new sense of nationhood, then we must de-emphasise the extent to which the USKL is characterised as an essentially Akkadian document with Sumerian additions. It is likely that the Kish A list was probably based on Kishite sources, mediated by the Akkadians. However, in my opinion, we should see the USKL as a whole as part of a ‘Sumerian campaign’, with the transfer formulae and the Uruk A* and the Akkad king lists compiled essentially from local literary and epigraphical sources.

Sargon’s Place in the USKL: Conclusions

I have argued above that, in the USKL, Sargon was placed at the ‘chronological confluence’ of Kish A and the Uruk A* king lists.

[Text to follow)

References

Dalley S., “Kish and Hursagkalama: An Assessment of the Cities’ History and Cults in the Light of Information from Cuneiform Texts”, in:

Wilson K. L. and Bekken D. (editors), “Where Kingship Descended from Heaven: Studies on Ancient Kish”, (2023) Chicago I, at pp. 23-47

Gabriel, G. I.,"The ‘Prehistory’ of the Sumerian King List and Its Narrative Residue", in:

Konstantopoulos G. and Helle S., “The Shape of Stories”, (2023) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 234-57

Steinkeller P., ‘The Sargonic and Ur III Empires’, in:

Bang P. F. et al. (editors), “The Oxford World History of Empire (Vol. 2): The History of Empires”, (2021) New York, at pp. 43-72

Kesecker N. T., “Lugalzagesi: the First Emperor of Mesopotamia?”, Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 12:1 (2018) 76-95

Kraus N., “The Weapon of Blood: Politics and Intrigue at the Decline of Akkad”, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, 108:1 (2018) 1–9

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2017) Boston and Berlin

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 1-130

Zólyomi G., “The Vase Inscription of Lugal‐zagesi and the History of his Reign”, Notes for a seminar held at the Institute for Advanced Studies, Budapest (2013)

Glassner J.-J., “Mesopotamian Chronicles’, (2004) Atlanta GA

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-292

Goodnick Westenholz J., “Legends of the Kings of Akkade”, (1997) Winona Lake, IN

Wilcke C., “Amar-girids Revolte gegen Narām-Suʾen", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie”, 87:1 (1997) 11-32

Cooper J. S. and Heimpel W., “The Sumerian Sargon Legend”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 103:1 (1983) 67-82