Sumerian King List (SKL)

Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: USKL I: Putative Kishite King List (KKL)

Topic: USKL II: Putative Sargonic King List

Sumerian King List (SKL)

Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL)

Topic: USKL I: Putative Kishite King List (KKL)

Topic: USKL II: Putative Sargonic King List

Putative Uruk King List of Utu-hegal and the USKL

‘Uruk I- III’ Kings in the USKL and the SKL

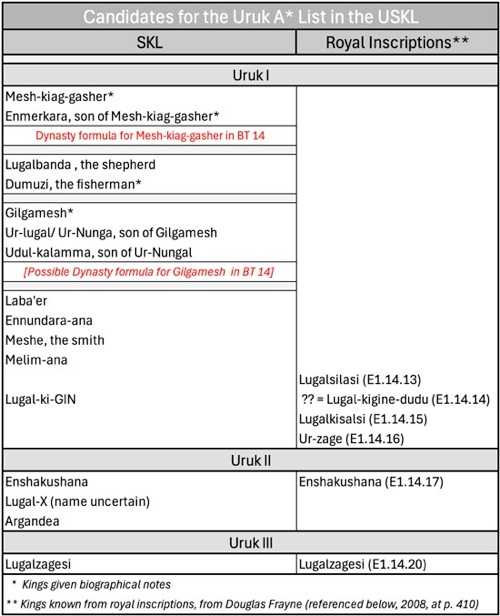

Table 7

As noted above, there is a long lacuna in the surviving USKL text between King Meshnune of Kish and King Sargon of Akkad. Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) observed that the completion of this lacuna is extremely problematic. However, as he pointed out, we at least know the name of the last king recorded in it: he must be King Lugalzagesi of Uruk, whom Sargon of Akkad famously defeated, thereby becoming the king of both Akkad and Sumer. Steinkeller considered (at pp. 274-5) the possibility (his ‘option a’) that all of the kings in this lacuna were kings of Uruk. However, he had two problems with this option:

✴he estimated that there would not have been room for all of the 15 other kings of Uruk who were named before Lugalzagesi in the SKL (12 in the Uruk I dynasty and 3 in the Uruk II dynasty); and

✴the inclusion of the earliest of them would, in any case, have violated:

“... the diachronic principle to which the USKL otherwise religiously subscribes”.

However, he also rejected other options based on the SKL (his options b and c), and observed that:

“... there seems to be no possibility of resolving these questions at this time.”

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, note 16, at p. 237) argued that:

“Uruk is the most likely candidate for reconstructing the missing section of the text. This hegemony ... probably did not include its first five legendary rulers (Mesh-kiag/kin-gasher; Enmerkara; Lugalbanda; Dumuzi; and Gilgamesh).”

In Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming), he also argued for the omission of the next two Uruk I kings, Ur-lugal and Udul-kalama, who were both described as descendants of Gilgamesh in the SKL. In this scenario, the long lacuna therefore contained:

✴Laba’er and the next four Uruk I kings;

✴the three Uruk II kings; and

✴Lugalzagesi (the sole Uruk III king);

whom Gabriel assumed would be easily accommodated (along with two sets of (‘transfer of dynasty’ formulae) in the lacuna. The problem with this hypothesis is that the lacuna would have started with formulae relating to the transfer of kingship from the otherwise-unknown Meshnune of Kish to the otherwise-unknown Laba’er of Uruk, a major even event that is nevertheless unrecorded in any other surviving source.

A more fundamental problem with any attempt to complete the USKL lacuna with names from the SKL is that the latter seems to have ignored the epigraphic evidence for the later Uruk kings: as Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008a, at p. 410) observed, royal inscriptions are known for five of these kings before Lugalzagesi, while no more than two of these appear in the SKL:

✴Enshakashuna; and

✴possibly Lugal-kigine-dudu, assuming that he is the same man as the SKL Lugal-ki-Gin (as suggested, for example, by Gösta Gabriel, forthcoming).

Furthermore, as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2019, at pp. 141-2) observed, surviving literary sources indicate that:

“... the Ur III kings traced their descent primarily to the mythical, semi-divine kings of Uruk, such as Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh. Although it may have begun already under Ur-Namma, it was only during the reign of Shulgi that this development acquired its full formulation.”

For this reason, I would argue that it is most unlikely that a king list dedicated to Shulgi would have omitted Gilgamesh, particularly since he was recorded in the Ur III period as the hero who had liberated Uruk from the hegemony of Kish at the time of Enmebaragesi and his son, Akka. Instead, it seems to me that:

✴the ‘diachronic principle to which the USKL otherwise religiously subscribes’ in the surviving text were not observed for the pre-Akkadian period; and

✴for whatever reason, the USKL cannot have been the primary source for the SKL Uruk I and Uruk II king lists.

However, I do agree with Gösta Gabriel (as above) that all of the kings recorded in this lacuna were probably kings of Uruk, which means (somewhat surprisingly) that the USKL, probably recorded neither an ‘Ur I’ nor an ‘Ur II’ dynasty.

As is shown in the first two columns of Table 7, the SKL listed 22 kings of Uruk and/or Ur in the pre-Sargonic period. Since (as noted above), no more than nine of them (almost certainly including the Uruk III king Lugalzagesi) could have been listed in the USKL, about 13 of the other kings in the SKL list must have been later additions. More specifically, Catherine Mittermayer (referenced below, at p. 321), who probably slightly over-estimated the number of Uruk A* kings in the USKL, argued that this list was made up of:

✴the last seven Uruk I kings:

✴the three Uruk II kings; and

✴Lugalzagesi;

which would mean that:

✴the first five Uruk I kings (all of whom had enjoyed reigns of ‘super-human’ length); and

✴all of the Ur I and Ur II kings;

were later additions. Gösta Gabriel, who proposed a shorter lacuna in the USKL, largely accepted her hypothesis but transferred the son and grandson of Gilgamesh to his list of later additions to the USKL.

I agree that the SKL list from Mesh-kiag-gasher to Udul-kalamma (inclusive) certainly shows signs of later intervention, given the preponderance here of patronymics and biographical notes (as well as at least one and possibly two ‘dynasty formulae in BT 14). However, I do not agree that we can regard Gilgamesh as a later addition, given his importance to both Utu-hegal and Shulgi.

To take this further, we need to return to the diagram above, which I used above in the context of the putative Sargonic king list. The argument in favour of ejecting Gilgamesh from the USKL is that his 126 year reign in the SKL consigns him to the mythical period, which had ended at Kish with the 100 year reign of the Kish III queen Ku-Babu: in other words, his inclusion in the USKL after Ku-Babu and the Kish A kings who followed her would violate what Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 275) described as the:

“... the diachronic principle to which the USKL otherwise religiously subscribes.”

However, if we accept the Utu-hegal’s list quite possibly contained a list of ‘legitimate’ kings of Sumer that dated back to Gilgamesh (albeit with two ‘dynastic’ interruptions), then this objection falls away: the USKL followed the diachronic principle in and after the Sargonic period because this reflected the order in which the relevant events had actually happened. In other words, the Uruk A* list in the USKL might well have started with Gilgamesh, the Urukean hero-king who had liberated Uruk from the hegemony of Enmebaragesi or Akka of Kish.

Returning now to Table 7, I would argue that:

✴the prime candidates for the USKL Uruk A* list based on both the surviving epigraphic evidence and the evidence of the SKL include:

•Gilgamesh;

•Lugal-kigine-dudu (= SKL Lugal-ki-GIN ?);

•Mesh-Ane-pada;

•Enshakushana; and

•of course, Lugalzagesi;

✴all the clearly mythical kings in the SKL Uruk I list would have come from literary sources;

✴the Ur I kings, Mesh-Ane-pada, his son, Mesh-kiag-nuna, Elilu and (probably) Balulu, would have come from epigraphical sources; and

✴we can reasonably regard the two Ur II kings of later duplicates of the first two Ur I kings.

The source of the names of the other SKL names in Table 7 remains unclear.

Akkad List in the USKL

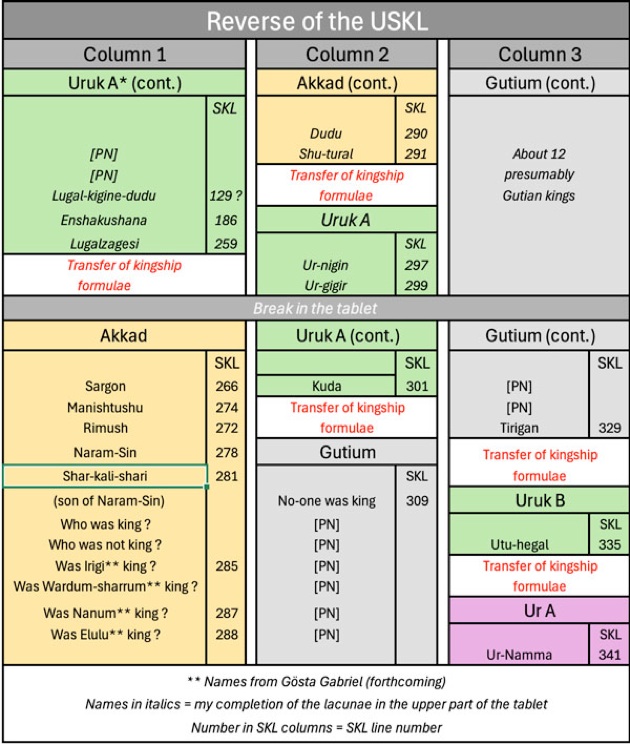

The first surviving lines in on the USKL reverse (reverse col. 1, lines 16’-27’) begin with the first five kings of the dynasty of Akkad:

✴Sargon (SKL 266);

✴his sons, Manishtushu (SKL 274) and Rimush (SKL 272);

✴his grandson, Naram-Sin (SKL 278); and

✴Shar-kali-shari, who is explicitly described as the ‘son of Naram-Sin’ (SKL 281).

In the SKL, Rimush ruled before Manishtushu (see, for example, Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, referenced below, in Table 5, at p. 18): although one might expect the USKL to be more accurate here than the later recensions, evidence from a surviving inscription of Rimush favours the order of these kings in the SKL.

The USKL text then indicates that, following Shar-kali-shari, four kings laid claim to the throne. In the SKL, these kings (who ruled for a total of 3 years in what is usually dubbed the ‘period of confusion’) were followed by:

✴Dudu (line 290); and

✴Shu-tural, son of Dudu (line 291), the last of 11 kings of Akkad.

Both of these kings are known from royal inscriptions in which each has the title mighty king of Akkad. As Nicholas Kraus (referenced below, at p. 7) observed, they:

“... strove to restore Akkad to its former glory. Those efforts are recorded in royal inscriptions and administrative records that reveal that:

✴Dudu defeated Umma and Girsu;

✴Akkad fought a battle against Uruk and Nagsu; and

✴Adab recognised Dudu and Shu-tural as sovereigns at some point during their reigns.”

We can therefore safely assume that they were recorded at the start of the lacuna in reverse column 2 of the original USKL text.

Uruk A List in the USKL

In the SKL, we read that, after the reign of Shu-tural:

“Akkad was struck down with weapons [and] the kingship was carried away to Uruk”, (lines 295-6).

It then recorded the reigns of 5 kings of Uruk:

✴Ur-nigin (SKL 297);

✴Ur-gigir (SKL 299);

✴Kuda (SKL 301);

✴Puzur-illi (SKL 302); and

✴Ur-Utu (SKL 303).

As Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993, at pp. 274-7) observed, the first three of these kings are known from surviving inscriptions:

✴an inscription from Uruk (RIME 2: 13: 1: 1, P462106) records the building of a temple to the goddess Nanshe by:

‘Ur-gigira, viceroy of the god Dumuzi, son of Ur-nigin, mighty man, king of Uruk, and his mother’;

✴the inscription on a mace head from Uruk (RIME 2: 13: 2: 2001, P462107) records Ur-gigra himself as:

‘Ur-gigira, mighty man, king of Uruk’; and

✴an inscription from Ur (RIME 2: 13: 3: 1, P462108), which records a temple administrator named Kuda, might refer to the Kuda of the king lists prior to his enthronement at Uruk.

Since Kuda was also the name of the first king recorded in the first surviving line in reverse column 2 of the USKL, we might reasonable assume:

✴with Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming), that the preceding lacuna contained:

•transfer of kingship formulae from Akkad to Uruk; and

•records of the reigns of both Ur-nigin and Ur-gigir; and

✴since Kuda is the only Uruk kong named before the transfer of kingship‘ formulae, then Puzur-illi and Ur-Utu were later additions.

However, I doubt that Shulgi’s scribe wished to imply that Ur-nigin had taken over all of the lands that had previously been ruled by Shu-tural: in my view, it is much more likely that the transfer of kingship formulae in the missing text implied that, under Ur-nigin, Uruk had thrown off the hegemony of Akkad.

Gutian List and Uruk B Lists in the USKL

We now come to the first surviving ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae in the surviving text of the USKL (at reverse column 2, lines 15’-18’): in the reign of Kuda:

Uruk was struck with weapons.

Its kingship was carried to the ummanum (the Old Akkadian word for horde or army).

The ummanum had no king: they ruled themselves (shared command ??) for three years.

In the SKL (at lines 307-8), the kingship was carried to ugnim gu-tu-um (where ugnim is the Sumerian equivalent of ummanum and gu-tu-um identifies the army in question as that of ‘Gutium’).

In the USKL (as summarised in the table above), these ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae were followed by:

✴6 Gutian kings in the rest of column 2;

✴about 12 (presumably Gutian) kings in the now-lost upper part of column 3; and

✴3 Gutian kings in the rest of column 3, the last of whom was Tirigan, who ruled for only 40 days.

Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, referenced below, Table 7, at p. 20) compared this list with those of all the other known SKL recensions. Interestingly, these sources are remarkably consistent in recording just over 20 kings in their respective lists, almost all of whom ruled for 7 years or less, despite the fact that there is great variation between them in respect of the names of these kings and the order in which they ruled. Furthermore, the two later SKL recensions that are unbroken to the end of the list agree with the USKL that the last Gutian king was Tirigan, who ruled for 40 days.

The USKL list is followed by the second surviving ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae in the surviving text (at reverse column 2, lines 15’-18’ (at reverse column 3, lines 12’-15’): in the reign of Tirigan:

The weapon was struck near (?) Adab.

The kingship was carried to Uruk.

In Uruk, Utu-hegal was king.

This translation is proposed by Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 243 and notes 35-6): he noted that these ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae differ in a semantic sense from the from the usual formulation (at SKL 332-5):

The Gutian army (ugnim gu-tu-um) was struck with weapons.

The kingship was carried to Uruk.

In Uruk, Utu-hegal was king.

Gösta Gabriel’s point was that:

“In the case of the Gutians’ defeat [in the USKL], the locative (or directive) case does not mark the object hit by the weapon, but [rather] the location at which the action took place. Since [a surviving inscription - see below - places] Utu-hegal’s final victory over the Gutians at a place close to Adab, [this particular] ‘collapse formula’ ... can be translated as: ‘The weapon was struck near (?) Adab’.”

As he pointed out (at note 36), his alternative translation removes the need to assume (with Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 276 and p. 281) that there must have been a set of ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae from the ummanum to Adab in the lacuna at the start of reverse column 3. Note however that Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, referenced below, Table 7, at p. 20) follow Steinkeller in this respect.

Gutium and the Gutians

The Gutians had been causing trouble in Mesopotamia since at least the reign of Shar-kali-shari at Akkad, as is evidenced by two of his year names (see Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 1993, at p. 183, entries k and n):

✴the year in which Shar-kali-shari laid [the foundations] of the temple of the goddess Annunitum and of the temple of the god Ilaba in Babylon, and captured Sharlag, king of Gutium; and

✴the year in which Gutium was defeated.

It seems likely that future pressure from the Gutians was a major cause of the period of confusion that followed Shar-kali-shari’s reign. Indeed, as discussed below, it is possible that at least one self-styled ‘king of Gutium’, Erridu-pizir, exercised hegemony over Akkad.

Erridu-pizir, the Mighty, King of Gutium and of the Four Quarters

Stele of Naram-Sin marking his victory over Lullubum, which king Shutruk-Nahhunte I of Elam moved from Sippar to Susa n the 12th century BC (as recorded in the Elamite inscription)

Image from the website of the Louvre Museum, where the stele is displayed

Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993, at p. 219) observed that:

“Curiously, the longest extant inscriptions of a Gutian ruler belong to Erridu-pizir, whose name does not even appear in [any of the known recensions of the SKL].”

He referred here to three Old Akkadian inscriptions (RIME 2: 2: 1: 1-3) that are known from copies on an Old Babylonian tablet from Nippur, each of which recorded that:

“Erridu-pizir, the mighty, king of Gutium and the four quarters, dedicated (this statue) to the god Enlil at Nippur” (see, for example, colophon 1 of RIME 2: 2: 1: 1, CDLI P462080, lines 94’-104’, which reproduced the caption inscribed on the base of the statue in question).

Here, we see Erridu-pizir behaving like the earlier Akkadian kings in recognising Enlil as the author of his victories and dedicating victory monuments to him at Nippur. However, perhaps the most striking thing about the inscriptions on these monuments is Erridu-pizir’s repeated and consistent use of the title ‘the mighty, king of Gutium and the four quarters’, a title that was probably devised by Naram-Sin.

The first inscription (RIME 2: 2: 1: 1, CDLI P462080) records Erridu-pizir’s victory over a now-unnamed king of Magda. The opening lines are now lost, but they probably introduced Erriu-pizir (with his usual titles), followed by the information that:

“ [The god [DN] is his (personal) god, the] goddess Ishtar-[Annuni]tum (is) his ... , (and) the god Ilaba, the mightiest of the gods, is his clan (god)”, (lines 5-11).

Ilaba had probably first appeared at Nippur in two of Sargon’s earliest-known inscriptions:

✴in RIME 2: 1: 1: 3, CDLI P461928, Sargon identified Ilaba as his personal god (at lines 1-2) and explained (in a caption recorded at lines 49 -54) that:

“The god Enlil gave ‘the weapons’ to Ilaba, the mightiest of the gods”; and

✴in RIME 2: 1: 1: 2, CDLI P461927 (at lines 16-21) he asserted that he had conquered fifty governors who were allies of Uruk, as well as the city of Uruk, by means of the ‘mace of Ilaba’.

Thereafter, as Stefan Nowicki (referenced below, at p. 70) observed:

“... the worship of Ilaba was undoubtedly a matter of great importance for the whole [Akkadian] clan, ... especially in Naram-Sin's inscriptions ...”

Thus, for example, Naram-Sin began one of the inscriptions that recorded his suppression of the ‘Great Revolt’ (RIME 2: 1: 4: 6, CDLI: P461982) with a statement that might well have inspired Erridu-pizir:

“Enlil, is his (personal) god, (and) Ilaba, the mightiest the gods, is his clan (god).”

Furthermore, as we have seen, one of the year names of Shar-kali-shari records that he laid the foundations of the temple of the goddess Annunitum and of the temple of the god Ilaba in Babylon. In short, it seems likely that, byassociating himself with Enlil, Ilaba and Ishtar-Annunitum, Erriu-pizir portrayed himself as the legitimate successor of Sargon, Naram-Sin and the Akkadian dynasty.

Andrew George (referenced below, at p. 139) translated another passage from this first inscription as follows:

“Thus, Erridu-pizir, mighty king of Gutium [and the] four quarters (says):

‘At that time, I fashioned my monument and placed my foot (sa’pum) at his (a captured enemy’s) throat”, lines 64’-69’).

George also pointed out (at p. 140) that:

“An identical reversion from first to third person happens in a parallel passage of an inscription of Naram-Sin (RIME 2: 1: 4: 26, CDLI P462024, at lines 82-102) known from an Old Babylonian copy found at Ur.”

This correspondence offers further support for the hypothesis that Erriu-pizir consciously followed precedents set by Akkadians in general and Naram-Sin in particular for his victory inscriptions at Nippur.

The second inscription ((RIME 2: 2: 1: 2, CDLI P462081) records Erridu-pizir’s response when king Kanishba of Simurrum raised his own people and those of Lullubum in revolt against him (see lines 9-28). These tribe, who occupied strategically-important locations in the central Zagros, had also troubled the Akkadian kings:

✴a year name of Sargon and two year names of Naram-Sin refer to campaigns in Simurrum (see Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 412 and 45); and

✴the Old Akkadian inscription (RIME 2: 1: 4: 31, CDLI P462029) on the stele illustrated above, which depicts Naram-Sin standing on a heap of enemy prisoners, identifies the enemy in question as the ‘mountain people of Lullubum’ (at lines 5’-6’).

In his inscription, Erridu-pizir seems to say that Kanishba’s revolt had broken out under:

“... my father, Enrida-pizir, the mighty, king of Gutium and of the four quarters”, (see lines 12-20).

If so, then it would seem that:

✴Enrida-pizir had established hegemony over a region that had probably been central to the Akkadians’ eastwards expansion; and

✴this inscription celebrated Erridu-pizir’s restoration of this hegemony.

Then, after a break in the text, we read that:

“... the goddess Ishtar had stationed the army (ummanum) in Akkad. The whole army assembled for him (Erridu-pizir) (and) went to Simurrum. He entered … (while) it (the army?) was making offerings of large male goats to the gods in Akkad”, (lines 39’-56’).

This suggests that Akkad itself formed part of the territory that first Enrida-pizir and then Erridu-pizir controlled from their ‘capital’ in Gutium.

However, nothing in our surviving sources suggests that Erridu-pizir controlled territory south of Nippur. While it is dangerous to argue from silence, I suggest that he did not appear in the USKL because:

✴Shulgi’s purpose in commissioning the USKL was to represent Ur-Namma as the legitimate heir of the kings of Uruk and, in particular, of Gilgamesh; and

✴Erridu-pizir did not feature in its list of Gutian kings because he had held power in the north at the time that the Uruk A kings had ruled in Uruk.

Utu-hegal of Uruk

As we have seen, the ‘Uruk B’ dynasty of the USKL contained only a single ruler, Utu-hegal, whose victory over Tigrian near Adab ended the turmoil that the Gutian invasion had inflicted on Uruk (along with much of the rest of Mesopotamia). Importantly, direct evidence for this claim survives in the form of three Old Babylonian copies of the inscription from a ‘victory’ monument of Utu-hegal, at least one of which came from Nippur. This inscription began (rather graphically) by describing how Enlil had commanded the obliteration the name of:

“... Gutium, the fanged snake of the mountain ranges, a people who:

✴acted violently against the gods;

✴took the kingship of Kiengi away to the mountains;

✴filled Kiengi with wickedness;

✴took wife from husband and child from father, filling the land with wickedness and violence”, (RIME 2:13:6:4; CDLI. P433096, lines 1-14).

The man whom Enlil chose for this task was:

“... Utu-hegal, the mighty man, king of Uruk, king of the four quarters [of the world], the king whose utterance cannot be countermanded, to obliterate [the Gutian] name”, (lines 15-23).

As Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993, at p. 280) observed:

“Noteworthy is the king's adoption of the title 'king of the four quarters', last used by:

✴Naram-Sin; and

✴the Gutian ruler Erridu-pizir.

Furthermore, [he] may have received special recognition by the Nippur authorities: in [this] text dealing with his expulsion of the Gutians, [he] relates that it was the god Enlil who had commissioned him to drive out the foreigners. We may also note that the same composition is known from at least one Nippur tablet copy, [which suggests that it was] transmitted in the Nippur schools.”

This inscription also contained an unusually detailed account of the ensuing battles:

“ ... at daybreak [Utu-hegal] proceeded (to a point) upstream from Adab. He prayed to him (Utu, the sun god, saying):

'O, god Utu! The god Enlil has given Gutium to me. May you be my ally'.

In that place, he laid a trap for the Gutians (and) led (his) troops against them. Utu-hegal, the mighty man, defeated their generals”, (lines 90-102).

Tirigan fled but:

“The envoys of Utu-hegal captured [him], along with his wife (and) children, at Dabrum. ... Utu-hegal made him lie at the feet of the god U[tu] and placed his foot on his neck. (Utu-hegal) removed Gutium, the fanged serpent of the mountain ... He brought back the kingship of Kiengi”, (lines 114-129).

As Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 243) observed, in the USKL:

“... the Gutian hegemony is framed by two hegemonies in Uruk (Uruk A and Uruk B), suggesting that kingship ‘returned’ to that city when Utu-hegal’s rule began.”

He also drew attention to the fact that both the inscription and the USKL specifically referred to the defeat of the Gutians near the city of Adab. He concluded (at p. 244) that:

“The parallels between the inscription and the USKL indicate that the sequence Uruk A–Gutium–Uruk B [in the latter] can be ascribed with reasonable certainty to Utu-hegal. He altered pre-existing concepts of the past to bolster his claim to power in [Mesopotamia], codifying these into a recension of the SKL that has not survived, but whose structure was integrated into the USKL.

In Construction

Puzur-Inshushinak

Puzur-Inshushinak is well known from his surviving inscriptions at Susa. Interestingly, the name of his father, Shimpi-Ishhuk, which appears on some of these inscriptions (see below), does not appear in the AwKL, which suggests that Puzur-Inshushinak was (like Sargon and Ur-Namma) a ‘new man’. Importantly for the present discussion, he also appears in one of Ur-Namma’s royal inscriptions, which is known from an Old Babylonian copy from Isin:

“(I), Ur-Namma, mighty man, king of Ur, king of the lands of Sumer and Akkad, dedicated (this object) for my life. At that time, the god Enlil gave (?) ... to the Elamites. In the territory of highland Elam, they (Ur-Namma and the Elamites) drew up (lines) against one another for battle. Their (??) king, Puzur-Inshushinak, ... (the cities of) Awal, Kismar, Mashkan-sharrum, the lands of Eshnunna, the lands of Tuttub, the lands of Simudar, the lands of Akkad, all the people ...”, (RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 29, lines 11-23; see also the translation by Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 2008b, at p. 3).

Although it is not absolutely clear from the (now-lacunose) inscription, it seems that Ur-Namma claimed to have marched north (presumably after he had taken power at Uruk from Utu-hegal) and ‘liberated’ a number of territories (including ‘the land of Akkad) from the hegemony of Puzur-Inshushinak. Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 124) observed that, since the territory described by Ur-Namma:

“... was still under Akkadian dominion even under Shudurul, [the last-known king of Akkad], ... Puzur-Inshushinak must have gained control of Akkad thereafter.”

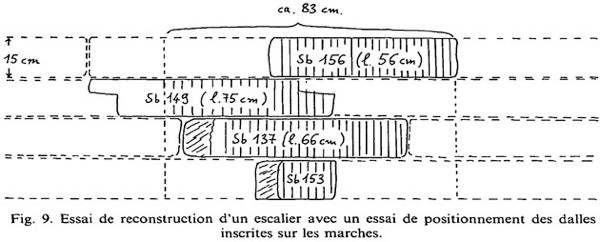

Reconstruction by Beatrice André and Mirjo Salvini (referenced below, at p. 68) of the relative positions of

some of the surviving fragments of the Akkadian inscriptions on the putative ‘steps of Inshushinak’ at Susa

Sb numbers relate to the numbers of the steps in the Musée du Louvre

Puzur-Inshushinak’ conquest of the ancient land of Sargon would have greatly enhanced his prestige, not least at Susa. This might well be reflected in the Old Akkadian inscriptions on a number of (mostly fragmentary) limestone slabs from Susa that are now in the Musée du Louvre (some of which are represented in the sketch above). Beatrice André and Mirjo Salvini (referenced below, at pp. 62-3) noted that two of them (Sb 156 and Sb 149) had apparently carried overlapping parts of the same text, which they translated (as a composite) as follows:

“To (his) Lord, [I am] Puzur-Inshushinak, mighty (danum) king of Awan, son of Shimpi-Ishhuk. [In] the year in which Inshushinak looked upon [me] and gave [me] the four quarters [of the world] to govern, [I] built [this] staircase ...”, (at p. 65, my translation of their French).

Piotr Steinkeller(referenced below, 2013, at p. 296) observed that:

“As is well known, the rule over the four quarters of the world had earlier been exercised by Naram-Sin, who was, in fact, the first Near Eastern monarch to make such a claim. It was also Naram-Sin who, for the first time, used the title of [‘mighty man’ (danum)]. We will be justified in assuming, therefore, that it was as a result of his capture of Akkad that Puzur-Inshushinak felt entitled to adopt these two designations for himself.”

Given this background, it is at least possible that Puzur-Inshushinak’s list of twelve kings of Awan (which went back some seven generations before to Sargon) might have been inspired by a much longer list of Naram-Sin’s Kishite and Akkadian predecessors that he had seen in Akkad. If so, Shulgi’s scribe might well have:

✴relied on the putative list of Naram-Sin’s Kishite and Akkadian predecessors (without regnal years or genealogy); and

✴used local sources to add the patronymics of:

•Akka, son of Enmebaragesi; and

•Meshnune, son of Nanne.

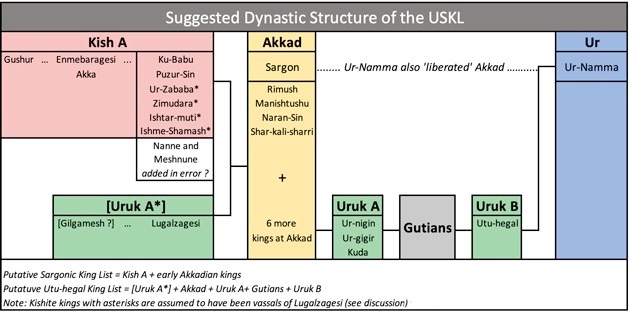

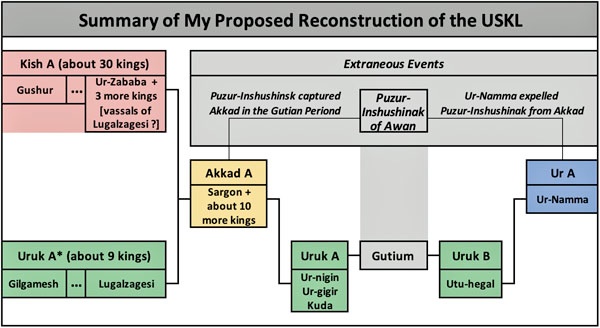

In this proposed schematic representation of the structure of the earliest known recension of the Sumerian King List,

I have named the successive dynasties (following the usage of Gösta Gabriel, referenced below, 2023) as:

Kish A - Uruk A* - Akkad - Uruk A - Gutium - Uruk B - Ur A

Gösta Gabriel (who coined the term ‘Uruk A*’ for the 8-9 rulers in this lacuna) took his candidates from the SKL Uruk I and Uruk II dynasties. However, in my view, it is important to bear in mind that:

✴while the earlier ‘Kish A’ list the compilation of the ‘Uruk A*’ list was probably compiled using one or more pre-existing Kishite/ Akkadian sources;

✴in the case of the ‘Uruk A*’ list, Shulgi’s scribes would have had local historical data for their compilation (and, indeed, they might have had an earlier local compilation to hand).

Furthermore, there would also have been a fundamental difference between:

✴the choices made here in the USKL, in which Shulgi would have represent himself as the latest of a series of kings of Uruk and Ur that dated back to Gilgamesh, having survived both an Akkadian and a Gutian interruption; and

✴the corresponding choices made for the SKL, in which the Isin kings sought to legitimise their rule, after having participated in the events that had culminated in the calamitous destruction of the city of Ur.

Finally, we have already seen that the compilers of the various SKL recensions relied on a number of sources (including but by no means confined to the USKL): in particular, it is likely that the USKL was the source for only one of the five earliest Uruk I kings in the SKL (i.e., Gilgamesh). In the light of this, there is no particular reason to think that a significant number of the other SKL Uruk I and Uruk II kings had previously appeared in the USKL.

Lacuna: Meshnune of Kish to Sargon of Akkad: Conclusions

My main conclusions regarding the completion of this part of the USKL is that:

✴Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023) was probably correct in his observations that:

•Uruk is the most likely candidate for the ‘dynasty’ of the kings in this lacuna (see note 16, at p. 237); and

•there were probably about nine of them (see p. 244); and

✴Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) was certainly correct in his observation that Lugalzagesi must have been the last of them.

However, I argued above against the idea that all of the Uruk A* kings subsequently found their way into the SKL (albeit that, as it happens, this was the case for at least three and possibly all of the four candidates that I have highlighted above as the most likely candidates ):

✴Gilgamesh;

✴Lugal-kigine-dudu;

✴Enshakushana; and

✴Lugalzagesi.

My reservations about depending on the SKL for the rest of this reconstruction arise because the SKL recensions:

✴name six kings of Uruk between Gilgamesh and Lugalzagesi who are otherwise unknown; but

✴do not name three significant kings of Uruk whose royal inscriptions still survive (all of which would have been available to Shulgi, presumably alongside others that are now lost).

In other words, it is possible that the compilers of the SKL relied on sources other than the USKL for any or all of:

✴the Uruk I kings after Gilagmesh (with the possible exception of Lugal-kigine-dudu, who might have been the same man as the SKL Lugal-ki-GIN); and

✴the Uruk II kings except Enshakushana.

Unfortunately, in my view, the limits to our knowledge of Shulgi’s likely sources makes it impossible to do more than guess at the names of the other five Uruk A* kings.

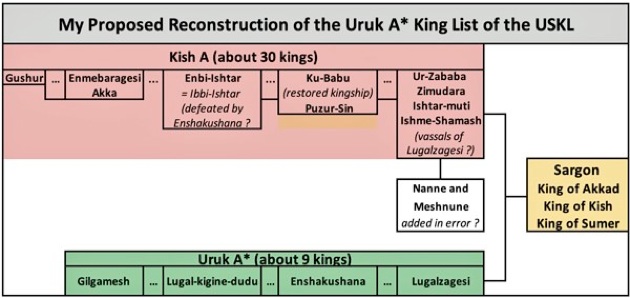

The most important conclusion to be drawn from the analysis set out in this page is that:

✴if there were indeed nine kings of Uruk between Meshnune and Sargon; and

✴in particular, if the first of them was indeed Gilgamesh;

then the ‘Kish A’ and the Uruk A* kings in the USKL must have ruled ‘in parallel’, since (for example) the ‘Kish A’ list was not interrupted after Enmebaragesi and Akka of Kish by the victory of Gilgamesh. In the diagram above, I have highlighted three other synchronisations between a Kish A and an Uruk A* king that offer some support to this proposition (as discussed further on the following page):

✴Ku-Baba of Kish might have thrown off the hegemony of Lugal-kigine-dudu or his son;

✴the Kishite ‘Ibbi-[Ishtar ?] of the SKL might be equated with Enbi-Ishtar, the Kishite king whom Enshakushana defeated; and

✴the Kishite king Ur-Zababa is characterised as a vassal of Lugalzagesi in the so-called ‘Sargon Legend’ (as discussed on the following page).

If accepted, then this hypothesis of the use of parallel lists of ‘Kish A’ and ‘Uruk A*’ kings in the USKL has important consequences for our wider understanding of the USKL:

✴in the (chronologically linear) SKL, Sargon and his Akkadian successors were represented as belonging to just one of a long line of Mesopotamian dynasties (which, in this case, happened to occupy a single ‘slot’ between the Uruk III and the Uruk IV dynasties); while

✴in the USKL, Sargon stands out as the first securely-established ruler of Kish, Uruk/Sumeria and Akkad.

In other words, the central message of the USKL would be that:

✴Sargon was the heir to the heaven-sent kingships of both Gushur and Gilgamesh; and

✴Ur-Namma was ‘the new Sargon’.

This proposition is supported by another observation made by Jasmina Osterman (referenced below, at p. 63): that the Ur III kings:

“... were the first to assume the title ‘lugal Kiengi Kiuri’ [king of Sumer and Akkad)], which remained a permanent part of the royal title that expressed authority over southern Mesopotamia until the Persian King Cyrus, [more than 1,500 years later].”

More specifically, this title was first assumed by Ur-Namma: as Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1997, at p. 12) observed:

“... a highly significant change in [Ur-Namma’s] status occurred during the period when the Nanna temple was under construction in Ur:

✴in the cone inscription commemorating the construction of the temenos wall (RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 11), Ur-Namma appears with the simple titles ‘mighty man, king of Ur’; whereas

✴in the corresponding brick inscription (RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 12) [from the temple itself, he has the] additional titles ‘lord of Uruk, and king of the lands of Sumer and Akkad’.

[He probably adopted these later titles] only after his trip to Nippur, when, on the death of Utu-hegal, his claim to exercise hegemony in the lands of Sumer and Akkad was duly recognised by the authorities [there].”

I will develop these arguments further in the following page (Topic: USKL: Sargon to Ur-Namma).

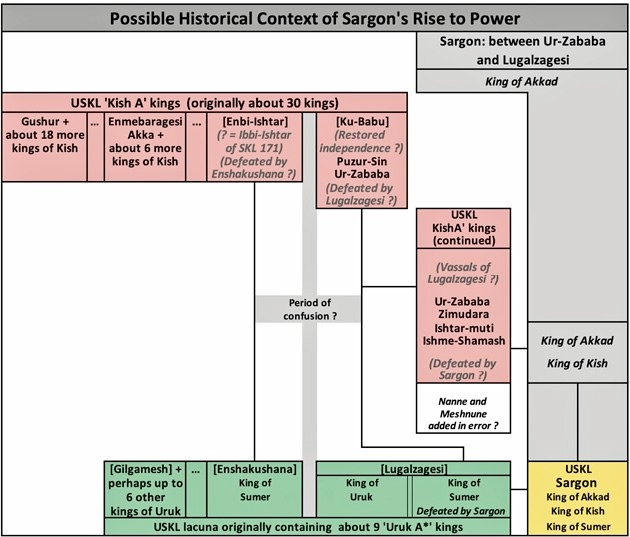

Sargon’s Rise to Power: Conclusions

In the schematic above, I have attempted to summarise the possible synchronisations between the ‘Kish A’ and the ‘Uruk A*’ kings, starting with

✴Enmebaragesi/Akka and Gilgamesh; and

✴Enbi-Ishtar/Ibbi Ishtar and Enshakushana.

I have then suggested a period of confusion that led to Enshakushana’s demise, in which:

✴Lugalzagesi (the erstwhile ensi of Umma) replaced him as King of Uruk;

✴Ku-Babu liberated Kish from Urukean hegemony and was succeeded by her son Puzir-Sin and her grandson Ur-Zababa; and

✴Lugalzagesi succeeded in restoring Uruk’s hegemony over Kish during the reign of Ur-Zababa, who then became his vassal.

The important point here is that, whatever the precise details, if one accepts that the ‘Kish A’ and the ‘Uruk A*’ lists in the USKL ran in parallel, then it is to be expected that:

✴Ur-Zababa and other kings of Kish would be included in the Kish A list, even if they ruled Kish under the hegemony of Lugalzagesi; and

✴they would be followed by the (chronologically parallel) list of Uruk A* kings.

It is possible that Sargon became the king of Akkad soon after Enshakushana’s demise (and acted as Ur-Zababa’s cupbearer in that capacity), but nothing in our surviving sources points in that direction. The more likely scenario is therefore one in which a precursor of the text that we know as the ‘Sumerian Sargon Legend’ recorded that, when Sargon became aware of Ur-Zababa’s malicious intentions towards him, he fled to Akkad and subsequently established himself as its king (as in the schematic).

As Marlies Heinz observed:

“By removing the local élites in the conquered cities, Sargon secured political control over the occupied territories once his military actions were over.”

The fact that he made particular mention of these administrative arrangements suggests that they constituted a major innovation in the way that this vast territory was governed.

According to the colophon associated with this copy, the original was written in front of an image of Lugalzagesi.

It is clear from the royal inscription mentioned above that Kish also became an important possession

“Sargon, lord of the land, altered the two sites of Kish: he made the two (parts of Kish) occupy (one) city.”

We might expect that the same sequence of formulae would be repeated in the USKL. However, this was not precisely the case: towards the end of column 6 of this earlier text (discussed in more detail below), we find the following formulae:

✴‘destruction formula’: Tirigan, the last Gutian ruler, was defeated near Adab (lines 21’-23’)

✴‘transfer formula’: The kingship was carried away to Uruk (lines 24’-25’)

✴‘beginning formula’: In Uruk, Utu-hegal was king: he ruled for 7 years (26’-27’)

✴‘destruction formula’: Uruk was destroyed (line 28’)

✴‘transfer formula’: The kingship was carried away to Ur (lines 29’-30’)

✴‘beginning formula’: In Ur, Ur-Namma: he ruled for 20 years (31’-33’)

In other words, it seems that the innovation of the ‘summary formula’ was introduced at some time after the reign of Shulgi. On this basis, we should assume that, in the original USKL text, there was a destruction formula’ followed by a ‘transfer formula’ both:

✴after Meshnune, son of Nannya, the last Kishite king; and

✴before Sargon, the first king of Akkad;

as indicated in the table above.

Niek Veldhuis (referenced below, at p. 393)

“The creation of the new lexical corpus in the early Old Babylonian period may be understood, paradoxically, as an attempt to preserve and guard traditional knowledge of Sumerian.

Sumerian, which was a dead language by this time, was of prime importance for political ideology; it was the language of royal inscriptions and royal praise songs.

The Sumerian King List, backed by a variety of Sumerian legendary texts and songs, explains how, since antediluvian times, there had always been one king and one royal city reigning over all of Babylonia.

This view implied that there were no separate local histories; all city-states were Babylonian, or, more properly of ‘Sumer and Akkad’, so that Enmerkar and Gilgamesh of Uruk, Sargon of Akkad, and Shulgi of Ur could all be celebrated as great predecessors.

The Old Babylonian literary corpus revolves around heroes who were kings of their respective cities, and gods who were city-gods of these same cities.

In trying to understand Old Babylonian Sumerian literature as a corpus, as a consciously collected set of texts important enough to teach, we may recognise that, almost without exception, the kings and heroes mentioned are those commemorated in the Sumerian King List.

Whatever the ‘historicity’ of this literature (accurate, skewed, legendary, mythical, or otherwise), this literature is Babylonian history as perceived and created by Old Babylonian scribes: it is the Sumerian King List fleshed out.”

Adab

RIME 2: 13: 6: 4; CDLI, P433096)

unu{ki}-ga {gesz}tukul ba-sag3

unu{ki}-ga {gesz}tukul ba-sag3

adab{ki} {gesz}tukul ba-sag3

Sazonov V., “Universalistic Ambitions, Deification and Claims of Divine Origin of Mesopotamian Rulers in Early Dynastic and Sargonic Periods”, in:

Kämmerer T. R., Kõiv M. and Sazonov V. (editors), “Kings, Gods and People: Establishing Monarchies in the Ancient World”, (2016) Münster, at pp. 31-62

Cooper J., "’I Have Forgotten my Burden of Former Days’: Forgetting the Sumerians in Ancient Iraq”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 130:3 (2010) 327-35

Abbreviations

RIME 1 = Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008)

RIME 2 = Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993)

Other References

Dalley S., “Kish and Hursagkalama: An Assessment of the Cities’ History and Cults in the Light of Information from Cuneiform Texts”, in:

Wilson K. L. and Bekken D. (editors), “Where Kingship Descended from Heaven: Studies on Ancient Kish”, (2023) Chicago I, at pp. 23-47

Gabriel, G.. "The ‘Prehistory’ of the Sumerian King List and Its Narrative Residue", in:

Konstantopoulos G. and Helle S., “The Shape of Stories”, (2023) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 234-57

Osterman J., “From ki-en-gi to Šumerum: How Sumer was Created ?”, Radovi HSP, 54:3 (2022) at pp. 39-72

Sommerfeld W., “Old Akkadian”, in:

Vita J.-P., (editor), “History of the Akkadian Language”, (2021) Boston and Leiden, at pp. 513-663

Steinkeller P., ‘The Sargonic and Ur III Empires’, in:

Bang P. F. et al. (editors), “The Oxford World History of Empire (Volume 2): The History of Empires”, (2021) New York, at pp. 43-72

Heinz M., “Sargon of Akkad: Rebel and Usurper in Kish”, in:

Heinz M.and Feldman M. H., “Representations of Political Power: Case Histories from Times of Change and Dissolving Order in the Ancient Near East”, (2019) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 67-86

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2019) Boston and Berlin

Kesecker N. T., “Lugalzagesi: the First Emperor of Mesopotamia?”, Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 12:1 (2018) 76-95

Kraus N., “The Weapon of Blood: Politics and Intrigue at the Decline of Akkad”, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, 108:1 (2018) 1–9

Cooper J., “Sumerian Literature and Sumerian Identity”, in:

Ryholt K. and Barjamovic G. (editors), “Problems of Canonicity and Identity Formation in Ancient

Egypt and Mesopotamia”, (2016) Copenhagen, at pp. 1-18

Nowicki S., “Sargon of Akkade and His God: Comments on the Worship of the God of the Father among the Ancient Semites”, Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 69:1 (2016) 63-82

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 1-130

Steinkeller P., “Puzur-Inshushinak at Susa: A Pivotal Episode of Early Elamite History Reconsidered”, in:

de Graef K. and Tavernier J. (editors), “Susa and Elam: Archaeological, Philological, Historical and Geographical Perspectives: Proceedings of the International Congress Held at Ghent University, December 14–17, 2009”, (2013) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 293-318

George A., “Erridupizir’s Triumph and Old Akkadian Sa’pum (Foot)”, in:

Barjamovic G. et al. (editors), “Akkade is King: A Collection of Papers by Friends and Colleagues Presented to Aage Westenholz on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday (15th of May 2009)”, (2011) Leiden, at pp.139-41

Veldhuis N. , “Guardians of Tradition: Early Dynastic Lexical Texts in Old Babylonian Copies”, in:

Baker H. D. et al. (editors), “Your Praise Is Sweet: a Memorial Volume for Jeremy Black from Students, Colleagues and Friends”, (2010) London, at pp. 379-400

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Vol. 1: Presargonic Period (2700-2350 BC)”, (2008) Toronto

Frayne D. R. (2008b), “The Zagros Campaigns of the Ur III Kings”, Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies, 3 (2008) 33-56

Rubio G., “Šulgi and the Death of Sumerian”, in:

Michalowski P. and Veldhuis N. (editors), “Approaches to Sumerian Literature. Studies in Honour of Stip”, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Supplemental Series 1, (2006) at pp. 167-79

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-292

Goodnick Westenholz J., “Legends of the Kings of Akkade”, (1997) Winona Lake, IN

Wilcke C., “Amar-girids Revolte gegen Narām-Suʾen", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie”, 87:1 (1997) 11-32

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Early Periods, Vol. 2: Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2334–2113 BC)”, (1993) Toronto, Buffalo and London

André B. and Salvini M., “Réflexions sur Puzur-Inshushinak”, Iranica Antiqua, 24 (1989) 53–72

Cooper J. S. and Heimpel W., “The Sumerian Sargon Legend”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 103:1 (1983) 67-82